Signalment:

17-year-old, neutered male, quarterhorse, (

Equus caballus).Horse developed severe atrophy of facial muscles on the left side

of the face 2 months prior to presentation to the teaching hospital. The weekend

prior to submission the patient developed rear limb ataxia. Probing palpation

of the cervical region revealed hyperesthesia and hyper-responsiveness. Probing

around the mid cervical region did not elicit a response. Treatment with

dexamethasone yielded some improvement in clinical signs. The horse was

euthanized at the owner elected request.

Gross Description:

The muscles on the left side of the face were diffusely atrophied

and hemorrhage was present in the anterior compartment of the right eye. There

was narrowing of the spinal canal between C2 and C3. The dura mater at the

C2-C3 articulation was focally reddened. The third cervical vertebral body (C3)

contained a 2.5 x 1.5 cm region of red and depressed tissue (bony

sequestration) rimmed by thick white tissue (fibrosis) at its ventral border.

The dorsal vertebral body of C2 also had a 1.5 cm linear band of firm white

tissue (fibrosis) that traversed the bone in a dorsal-ventral direction.

Histopathologic Description:

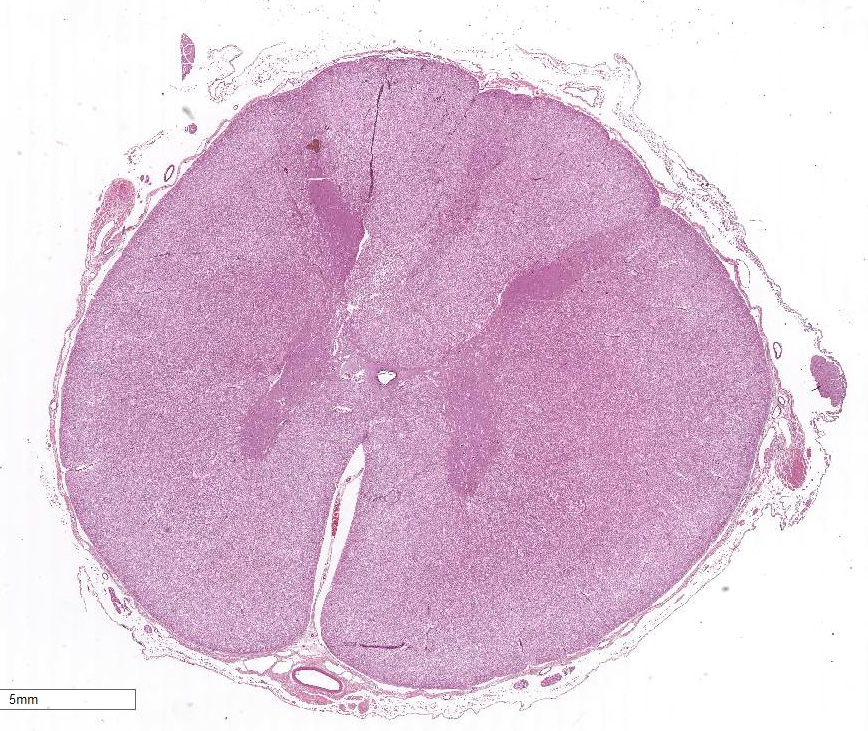

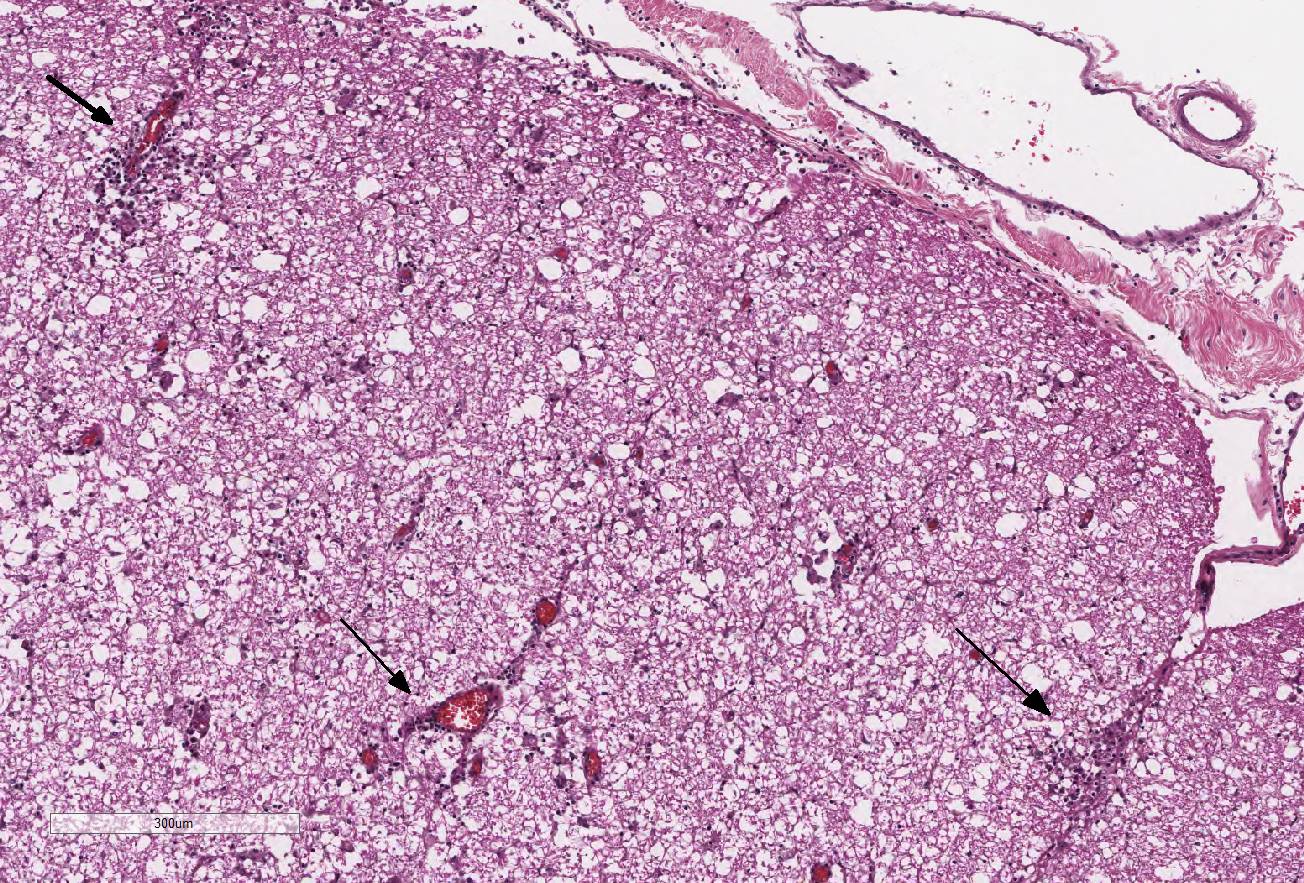

Extending from just caudal of C1 to C5, there is a locally

extensive area of rarefaction and multifocal to coalescing accumulations of

glial cells and gitter cells, unilaterally involving the dorsal funiculus at

the level of the gracile and cuneate fasciculi. Spinal cord inflammation is

most concentrated at C3 and includes significant perivascular cuffing, few to

moderate lymphocytes and plasma cells and scattered eosinophils. The associated

spinal gray column is unilaterally affected with similar inflammation in these

sections. Numerous swollen axons (spheroids) are present at C2 and C3 spinal

cord sections. At the level of C2, there are occasional glial nodules in the

contralateral dorsal funiculus as well. Small numbers of lymphocytes and plasma

cells are diffusely present in the meninges and are more concentrated over the

dorsolateral funiculus. The dorsal spinal nerve root ganglia are infiltrated

with small numbers of lympho-cytes and plasma cells at the level of C2 and C3.

Cervical spinal cord (C1-C5): Meningo-myelitis,

nonsuppurative and eosinophilic, unilateral, focally extensive, severe with

spheroid formation, cervical spinal cord, dorsal funiculus.

Condition:

Myelomalacia

Contributor Comment:

The gross and histopathologic findings in this case are highly

suggestive of cervical stenotic myelopathy. The unilateral distribution of the

lesions coincides with the focus of stenosis observed in the spinal canal.

Microscopic changes in the spinal cord include rarefaction, accumulations of

glial and gitter cells, and lymphocytes, plasma cells, and scattered

eosinophils. The horse, in this case, was 17 years old, considerably older

than the typical case of cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy (8-18 months

and 1-4 years of age). However, several retrospective studies have documented

this condition in horses up to 22 years of age.

3,4

Cervical

vertebral stenotic myelopathy, commonly referred to as Wobblers syndrome, is

characterized by lesions in the spinal cord caused by narrowing of the spinal

canal or compression by the vertebral articular processes.

6,7 There

are two pathological syndromes: cervical vertebral instability (CVI) and

cervical static stenosis (CSS). Clinical signs for both pathological syndromes

include ataxia with the hindlimbs more commonly and more severely affected than

the forelimbs.

7 Cervical vertebral instability is characterized by

the narrowing of the spinal cord when the neck is ventroflexed. The cranial

articular process of the vertebral bodies project in a ventro-medial direction

and impinge on the spinal cord. C-3 to C-5 of the spinal cord is the most

affected area.

6 Young, rapidly growing horses between the ages of

8-18 months are predisposed to this condition. Breed dispositions include

Thoroughbreds and Quarter horses, and males are affected more often than

females. Contributing factors may be

ad libitum feeding of high-energy

and high-protein diet as well as copper deficiency.

6,7

Cervical

static stenosis is the less common syndrome. It is characterized by the

compression of the spinal cord at the level of C-5 to C-7 due to the thickening

of the ligamentum flavum and the dorsal laminae of the vertebral arches.

6

Predispositions are similar to those seen in CVI except horses aged one to four

years are commonly affected.

3 The position of the neck does not

determine whether or not the chord is compressed.

JPC Diagnosis:

Spinal cord, dorsal medial fasciculi: Necrosis, focally extensive,

asymmetric with lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic perivasculitis and lepto-meningitis,

quarterhorse,

Equus caballus.

Conference Comment:

This interesting case generated spirited discussion amongst

conference participants. While attendees essentially agreed with the

contributors histopathologic description and morphologic diagnosis, there was

no consensus for the histogenesis of the necrotizing lesion in the spinal cord

of this horse. The conference moderator offered an alternative inter-pretation

of an infectious cause, with Sarcocystis neurona causing acute onset

weakness, ataxia, and a focally extensive area of necrosis in the dorsal medial

spinal cord with corresponding lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic

leptomeningitis. The conspicuous eosinophilic component of the perivasculitis

and leptomeningitis in this case, may suggest a parasitic etiology.

S. neurona is an apicomplexan protozoan parasite which causes equine

protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM), a relatively common and severe neurologic

disease in horses. Opossums are the definitive host for the parasite and spread

the disease by fecal shedding of sporocysts into the environment.1

Unfortunately, no api-complexan schizonts or merozoites were observed in any

examined tissue sections. Other potential etiologies offered by conference

participants included acute intervertebral disc rupture and fibro-cartilaginous

embolism, although disk material was not visualized within the section.

As noted by the contributor,

the age of the horse (17-years-old) is a highly atypical presentation for both

cervical stenotic myelopathy and cervical static stenosis.2,3,5

While most cases of cervical stenotic myelopathy involve ventral compression of

the spinal cord and spinal nerves with Wallerian-type degeneration of the white

matter of the dorsal and ventrolateral spinal cord affecting the descending

spino-cerebellar tracts of both the pelvic and thoracic limbs,2,5 in

this section, the ventral and lateral spinal cord is relatively unaffected.

The lesions seen in the submitted section of spinal cord are primarily located

in the dorsomedial spinal cord at the level of the fasciculus gracilus and

fasciculus cuneatus.

Some conference

participants noted occasional scattered 2x5 um filamentous bacilli multifocally

throughout the neuro-parenchyma. The brain and spinal cord are exquisitely

susceptible to post-mortem autolysis and putrefaction. As a result, the

conference moderator cautioned attendees against overinterpreting artifactual

bacterial overgrowth within post-mortem tissue samples of the central nervous

system, especially when they are not associated with inflammation, as in this

case.

References:

1. Bowman

DD. Protozoans. In: Georgis Parasitology for Veterinarians. 9th

ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:104-105.

2. Janes JG, Garrett KS,

McQuerry KJ, et al. Cervical vertebral lesions in equine stenotic myelopathy. Vet

Pathol. 2015; 52:919-927.

3. Levine JM, Adam E, MacKay RJ, et al.

Confirmed and presumptive cervical compression myelopathy in older horses: A

retrospective study (1992-2004). J Vet Intern Med. 2007; 21:812-819.

4. Levine JM, Scrivani PV, Divers TJ, et

al. Multicenter case-control study of signalment, diagnostic features, and

outcome associated with cervical vertebral malformation-malarticulation in

horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2010; 237(7):812-822.

5. Reed

SM. Cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy: Pathogenesis. Proceedings of the

International Equine Neurology conference. College of Veterinary Medicine,

Cornell University, New York. 1997:45-49.

6. Thompson K. Bones and joints. In: Pathology

of Domestic Animals, 5th Edition. Edinburgh : Saunders; 2007:

44-46.

7. Zachary JF, McGavin DM. Nervous system. In: Pathologic Basis

of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2012:816, 833-835.