Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 10, Case 4

Signalment:

13-month-old, male, Sprague Dawley rat, Rattus norvegicusHistory:

Gross Pathology: A 2-cm in diameter, well-demarcated, firm, tan mass with a central area of necrosis was observed within the left masseter muscle of the rat.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

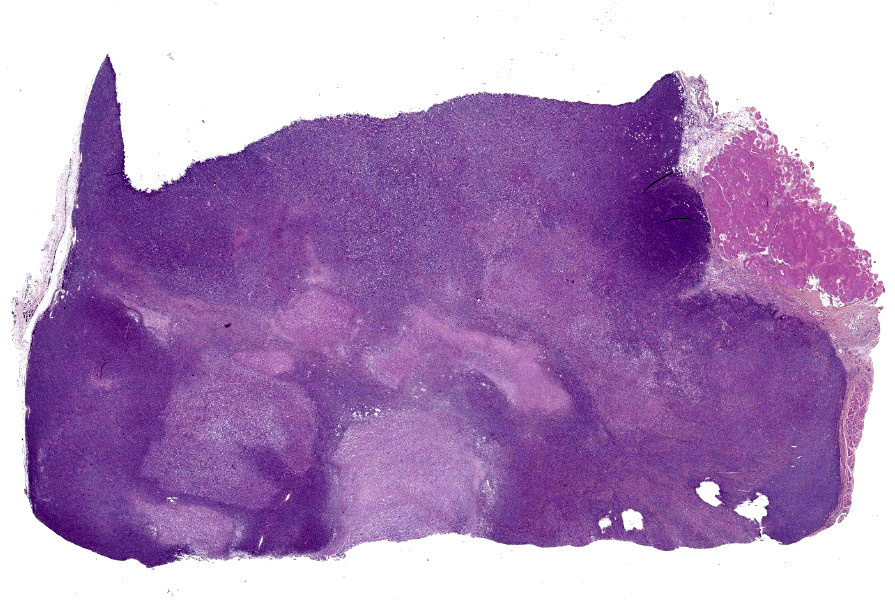

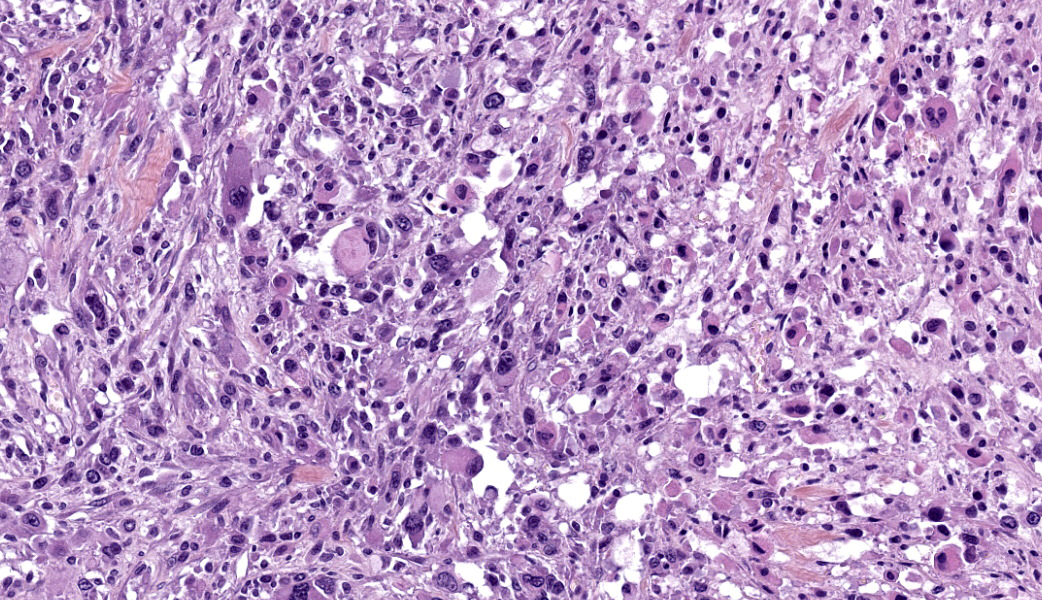

Left masseter muscle: Expanding and replacing up to 95% of the striated muscle on the tissue section, is a well-circumscribed, unencapsulated, highly cellular and heterogeneous neoplasm. The tumor is composed of tightly packed to loosely arranged round to elongated cells, haphazardly arranged or sometimes forming streams and bundles, separated by a moderate fibrovascular stroma. Some areas have a lower cellular density with increased amount of dense fibrous stroma.Neoplastic cells have rather distinct cell borders, a plump appearance, variable amount of an intensely eosinophilic cytoplasm, oval to elongate paracentral nuclei with finely stippled chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Round to racket-shaped or tadpod shapes cells (rhabdomyoblasts) are observed. Some cells have moreover an intensely eosinophilic appearance with a central acidophilic inclusion-like structure peripherizing the nucleus (rhabdoid cells). Numerous and scattered multinucleated giant cells are also observed.

There is marked cytologic atypia, namely anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, karyomegaly, macronucleolation, multinucleation, and bizarre mitotic figures. Mitotic figures average 10 per 10 high power fields and are often atypical.

Some preexisting dissected muscle fibers and adipocytes are present within the tumor.

Within the mass, there are several randomly distributed necrotic areas composed of eosinophilic cellular debris, viable and degenerate neutrophils. There are also lymphocytes, plasma cells and mast cells scattered among and at the periphery of the neoplasm. Surrounding tissue is compressed and neoplastic cells infiltrate the peripheral muscle fibers.

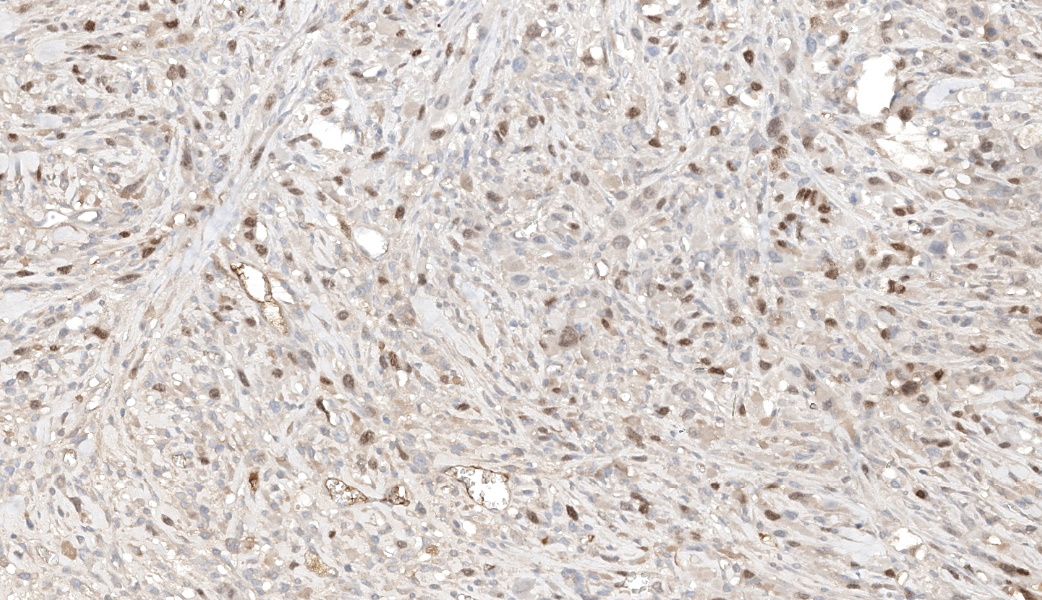

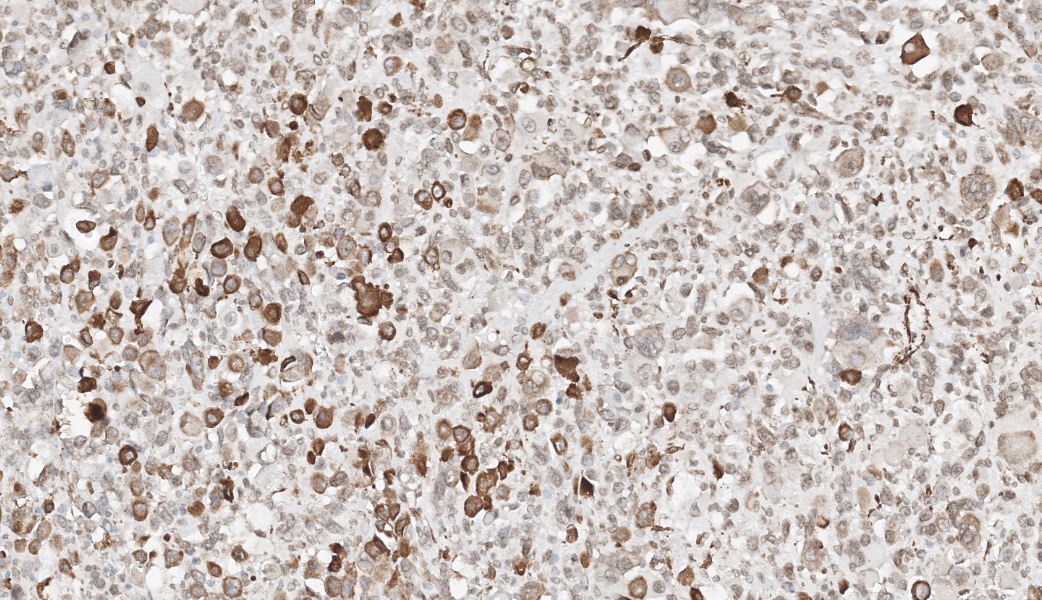

PTAH coloration was performed and showed very subtle striations in the tumor cells.

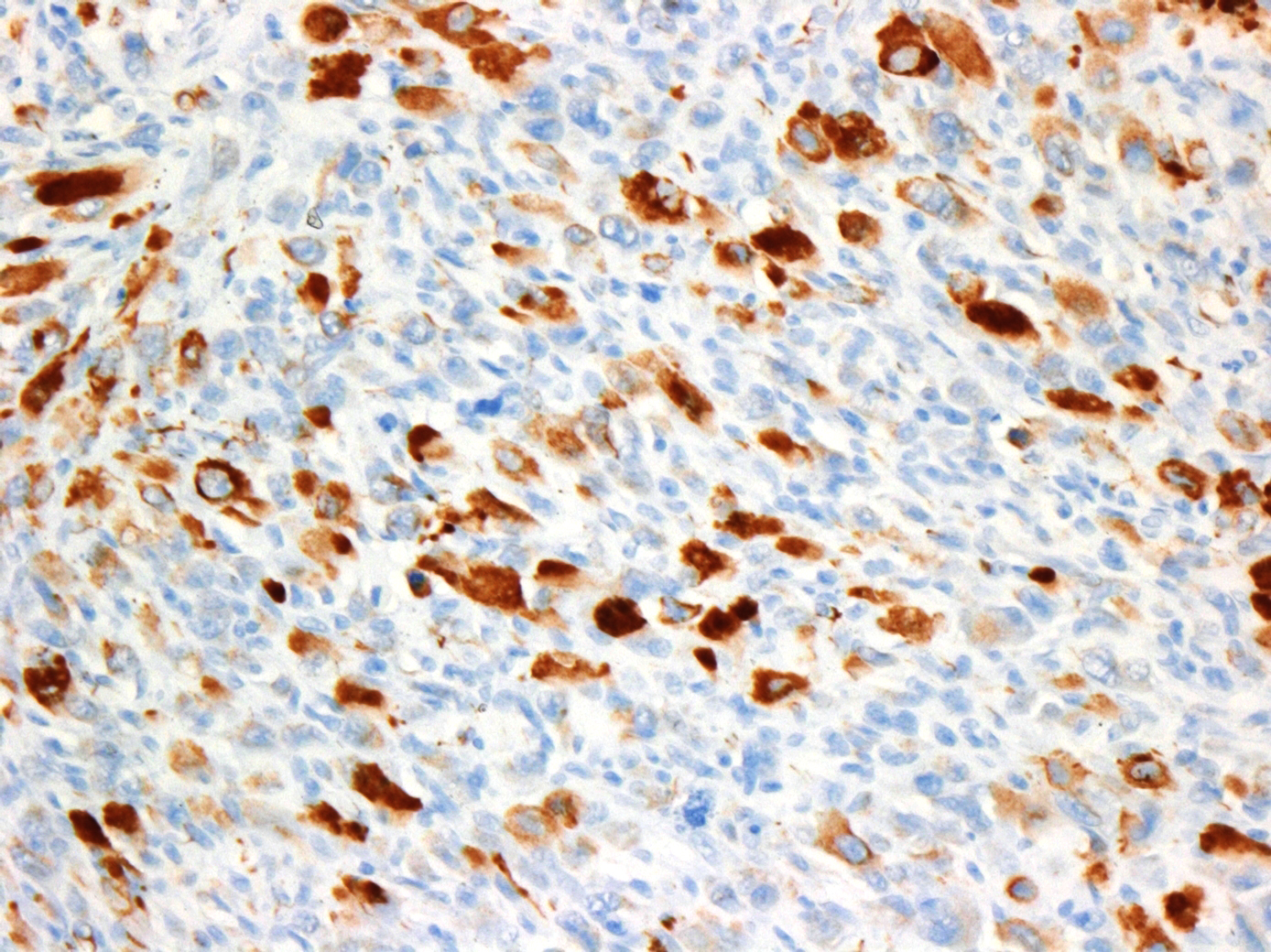

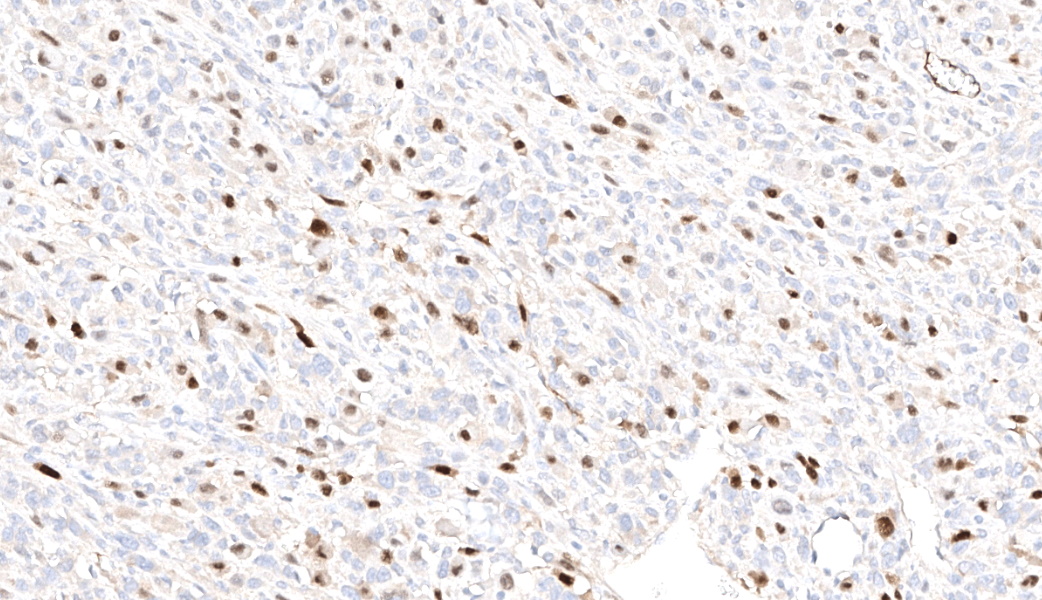

Immunohistochemistry was also performed for vimentin, myogenin and desmin. Tumor cells were strongly vimentin positive (intense cytoplasmic staining), and most cells were positive for myogenin (nuclear staining) and/or desmin (cytoplasmic staining).

Micrometastasis was observed in the associated lymph node and in the lungs (not present on slides)

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Left masseter muscle: Rhabdomyosarcoma, pleomorphic type.Contributor's Comment:

Rhabdomyosarcomas (RMS) are relatively rare mesenchymal neoplasms of skeletal muscle origin with varying myogenic differentiation that develop among several domestic animal species and in humans.3,5,8,9,15 RMS can encompass a variety of gross and histologic aspects.3 This tumor may be underdiagnosed due to these extreme variations in phenotype, age of onset, and cellular morphology that hinder diagnosis and classification.3The most aggressive forms of RMS have been described in juvenile dogs younger than 2 years and include alveolar RMS and embryonal RMS.3 Canine RMS has been described most commonly in the larynx and urogenital tract and were less frequently documented in the head, neck, and face.3,9 Gross findings include firm, tan to white, multilobular masses with varying degrees of hemorrhage and necrosis.3,9

Common histologic subtypes include embryonal, botryoid, alveolar, and pleomorphic RMS.1,3 Embryonal RMS and botryoid RMS are the most common forms in people and, seemingly, also in animals.5,8,15

Immunohistochemical (IHC) diagnosis of RMS in humans and dogs relies on detection of at least one muscle-specific marker (in particular, positive IHC labeling for desmin) and absence of smooth muscle markers.1,3,14 It was recently suggested MyoD1 and myogenin should be included with desmin as part of a diagnostic IHC panel for canine RMS.14

Embryonal RMS is composed of either round cells or cells that exhibit different stages of development from myoblast-like and elongated cells to myotube-like (“strap”) cells, that can be mononuclear or multinucleated in a myxoid stroma, with the majority of described cases arising from the head.3,15

Botryoid RMS is characterized by its submucosal location and its “grape-like” gross appearance. Histologically, it comprises mixed round and myotubular cells in mucinous stroma. It occurs most often in the trigone area of the urinary bladder in young large breed dogs.3,15

Alveolar RMS displays fibrous bands that divide small round cells into clusters and/or loose aggregates and can form thin fibrous septa.3

Pleomorphic RMS consists of haphazardly arranged plump spindle cells that may be admixed with scattered multinucleated cells, strap cells, racket-shaped cells, and large, round rhabdomyoblasts. Some pleomorphic RMS display cells with a rhabdoid morphology characterized by a peripherally located vesicular nucleus, prominent nucleolus, and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic hyaline inclusion-like structures.5 Cells exhibit marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis and bizarre mitotic figures.3,15 Diagnosis of pleomorphic RMS is generally made when the whole tumor is pleomorphic, areas with embryonal or alveolar morphology are absent, and myogenic differentiation has been confirmed by immunohistochemistry.3,15 This subclass can cause confusion since histologic evidence of skeletal muscle differentiation might not be obvious. Without immunohistochemical confirmation, such neoplasms may be diagnosed as anaplastic sarcomas.3

Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma has been reported in dogs, cats, cows, horses, mice and rats. 2,3,4,6,9,10,13,15 It occurs less frequently than alveolar and embryonal RMS in humans. It is found more often in adult humans and animals and arises almost exclusively within skeletal muscle.3 Noteworthy, development of pleomorphic RMS was described in a rat model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (as in this case) following double knock-out of p16, a tumor suppressor gene, and dystrophin protein.13

Contributing Institution:

Ecole Nationale Veterinaire Alfort, Paris France, 7 avenue due General de Gaulle, 94700 Maisons-Alfort – 01 43 96 71 00JPC Diagnoses:

Skeletal muscle: Rhabdomyosarcoma.JPC Comment:

Although it provided a relatively straightforward diagnosis, this case stimulated great discussion in conference on subtyping of rhabdomyosarcomas, which the contributor also did an excellent job of writing about in their comment. Participants were split on what to classify this particular rhabdomyosarcoma as and, while most felt it was more likely an embryonal subtype rather than a pleomorphic due to the presence of myoblast-looking cells and strap cells, participants ultimately decided to forgo a subtype in the final morphologic diagnosis as there is currently no reported difference in clinical outcome with the different subtypes.Other key points of conference discussion included a quick review of main sites for rhabdomyosarcoma development in other species. In dogs, these tumors often arise in the trigone of the urinary bladder, where they are usually of the embryonal subtype, and in the larynx. Although rhabdomyosarcomas frequently occur in places that lack skeletal muscle (i.e. the urinary bladder), it is important to remember that they arise from myogenic precursors, which are stem cells, and stem cells can do whatever they want.

This conference case is from a dystrophin-deficient Sprague-Dawley (SD) rat, a strain of SDs used to study Duchenne muscular dystrophy of humans. Muscular dystrophy patients are predisposed to the development of rhabdomyosarcoma due to the loss of dystrophin.7,13 Dystrophin normally functions to strengthen and stabilize muscle fibers via linking the actin cytoskeleton to the outer cell membrane and extracellular matrix. Loss of dystrophin leads to chronic damage of muscle cells and an increased rate of regeneration, which provides more chances for genetic mutations to occur.7 Dystrophin is also a tumor suppressor gene, and its loss can result in an increased rate of not just myogenic neoplasms, but in cancer overall, especially carcinomas of the head and neck.7

The rhabdomyosarcoma was first described by German physician Dr. Weber in 1854 as a malignancy of striated muscle. There is some speculation on this, but he may have first described this lesion in a human tongue.12 A more complete histologic definition was made in 1946 by Dr. Arthur Stout when he described distinct features of rhabdomyoblasts, which he stated appeared in “round, strap, racquet, and spider” shapes.12 The current classification system for rhabdomyosarcoma was introduced in 1958 by Drs. Horn and Enterline.

Rhabdomyosarcomas are neoplasms of skeletal muscle, which is a type of striated muscle. Skeletal muscle striations are composed of alternating dark and light bands (A and I bands) that result from the highly organized, repeating arrangement of myosin and actin filaments within sarcomeres. I-bands are separated by a dark line called a Z-band, so named from the German word "zwischen" for their dark, zigzagging linear appearance. In contrast, according to Disney, “Z-bands” are “bracelets that all zombies are equipped with that send doses of electromagnetic pulses into the body, keeping the wearers from returning to their former brain-eating state. If the Z-band goes offline, the zombies revert.” So, there’s that.

References:

- Agaram NP. Evolving classification of rhabdomyosarcoma. Histopathology. 2022;80(1):98–108.

- Aoyagi T, Saruta K, Asahi I, Hojo H, Shibahara T, Kadota K. Pleomorphic Rhabdomyosarcoma in a Cow. J Vet Med Sci. 2001;63(1):107–110.

- Caserto BG. A Comparative Review of Canine and Human Rhabdomyosarcoma With Emphasis on Classification and Pathogenesis. Vet Pathol. 2013;50(5):806–826.

- Castleman WL, Toplon DE, Clark CK, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma in 8 Horses. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(6):1144–1150.

- Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Rhabdomyosarcoma, in: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 2020, Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, p. 652 696.

- Inoue K, Yoshida M, Takahashi M, Cho Y-M, Takami S, Nishikawa A. Rhabdomyosarcoma in the Abdominal Cavity of a 12-Month-Old Female Donryu Rat. J Toxicol Pathol. 2009;22(3):195–197.

- Jones L, Divakar S, Collins L, et al.Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene product expression is associated with survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2025;15:10754.

- Meuten DJ., Cooper BJ., Valentine BA. Tumors of muscle, in: Tumors in Domestic Animals. p. 425-466. Wiley Blackwell 2017.

- Scott EM, Teixeira LBC, Flanders DJ, Dubielzig RR, McLellan GJ. Canine orbital rhabdomyosarcoma: a report of 18 cases. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016;19(2):130–137.

- Sher RB, Cox GA, Mills KD, Sundberg JP. Rhabdomyosarcomas in Aging A/J Mice. McNeil P, ed. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e23498.

- Spugnini EP, Filipponi M, Romani L, et al. Electrochemotherapy treatment for bilateral pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51(6):330–332.

- Tandon A, Sethi K, Pratap Singh A. Oral rhabdomyosarcoma: A review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4(5):e302-8.

- Teramoto N, Ikeda M, Sugihara H, et al. Loss of p16/Ink4a drives high frequency of rhabdomyosarcoma in a rat model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Vet Med Sci. 2021;83(9):1416–1424.

- Tuohy JL, Byer BJ, Royer S, et al. Evaluation of Myogenin and MyoD1 as Immunohistochemical Markers of Canine Rhabdomyosarcoma. Vet Pathol. 2021;58(3):516–526.

- Maxie MG, editor. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s pathology of domestic animals. Elsevier 2016.