Signalment:

Gross Description:

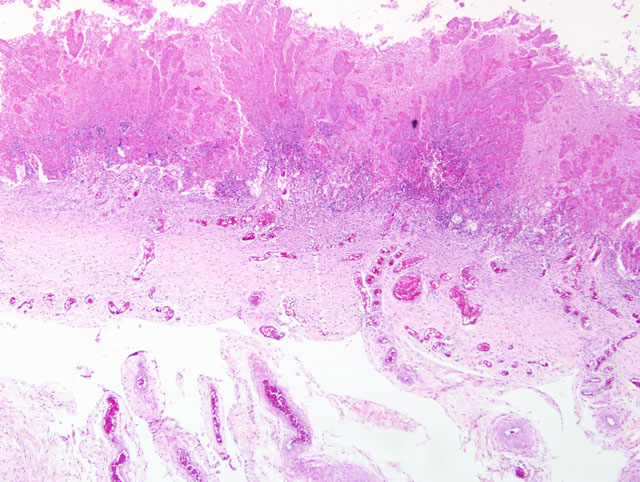

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Placenta: Marked pyogranulomatous placentitis, chronic with necrosis and squamous metaplasia.

2. Amnion: Membrane hyperplasia with moderate funisitis.

Lab Results:

Aerobic bacterial culture: Trace numbers of Delftia acidovorans, Acinetobacter lwoffi and Staphylococcus epidermidis.Â

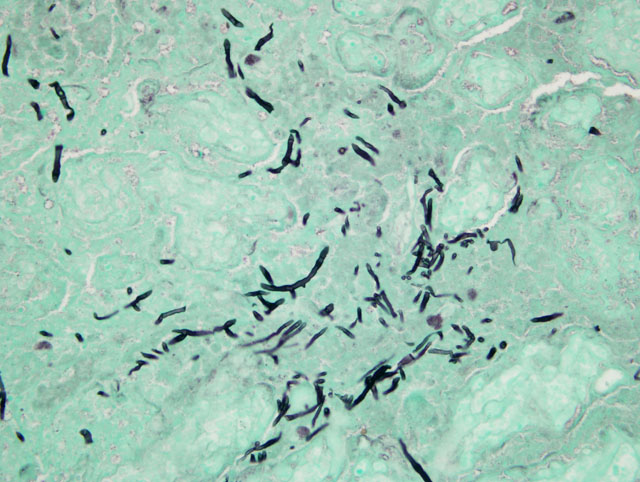

Fungal culture: Bipolaris sp.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Though recognized less often than bacterial placentitis, mycotic placentitis is still an important cause of reproductive loss. Mycotic placental infections are typically characterized by brown, thickened leathery lesions at the cervical star that indicates (as above) an ascending route of infection. Ascending mycotic infections can result in lesions restricted to the placenta only. Historically, this was hypothesized to be the reason for the delay in recognizing the importance of fungal abortions as well as the reason for the plea to submit fetal membranes along with the fetus for an accurate diagnostic work-up.(3) Certainly, the mycotic lesions can spread to the amnion and the fetus as well.

This horse was part of a group of horses that was under continual gestational monitoring and the placentitis was recognized and treated. The mare entered an uncomplicated parturition and the foal was born alive and healthy and as of this writing (4 months later) remains healthy. Unfortunate outcomes include fetal loss due to separation of the placenta or placental insufficiency or perinatal loss as an extension of either placental insufficiency (hypoxia) or infection of the fetus with the microorganisms causing the placentitis. In this case, there were trace numbers of bacteria and a dematiaceous fungus (Bipolaris sp.) isolated from the fetal membranes. Teeming numbers of fungi were seen associated with the placental lesion on GMS stains; however, on H&E stains, only a minority of the fungal hyphae seen was pigmented. As Bipolaris sp. exhibits rapid take-over growth in vitro, it is possible that a second fungal isolate was obscured. Otherwise, the inconspicuous nature of the pigmentation seen on H&E may be related to the age of the fungal growth within the lesion (intensity of pigmentation increases with time).

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

In addition to the microscopic lesions described by the contributor, participants noted that the allantoic epithelium is diffusely cuboidal to columnar (i.e. reactive), in contrast to the squamous epithelium typical of the normal equine allantoic membrane. The histologic finding of reactive allantoic epithelium may be of particular diagnostic utility in cases with suboptimal sampling of the affected chorion, such as in cases with only focal or multifocal placentitis where inflammation is not present in the microscopic sections, because it usually occurs as a diffuse change and suggests inflammation somewhere in the placenta. The large size of the equine allantois as a proportion of the entire fetal membranes renders the finding of reactive allantoic epithelium a useful microscopic sentinel for inflammation elsewhere in the placenta. This is well-illustrated by the finding in this case that both severely and minimally affected areas of chorion are present in most sections, but the allantoic epithelium is diffusely reactive. Additionally, participants noted foci of coagulative necrosis in the chorion; these are interpreted as areas of ischemia secondary to thrombosis, as substantiated by the presence of variable numbers of vascular thrombi in the section.

In both mares and cows with mycotic placentitis, Aspergillus fumigatus is the most frequent isolate; however, significant species differences in distribution reflect a fundamental disparity in pathogenesis. In mares, fungi usually ascend through a patent cervix, resulting in a chronic, focally extensive placentitis in the region of the cervical star. In cattle, by contrast, lesions initially develop in placentomes, reflecting hematogenous arrival from rumen or pulmonary infections.(4)

Prior to the conference, the moderator reviewed comparative placentation with conference participants, emphasizing equine placentation and placental pathology. As discussed by the contributor, lesion distribution is of tremendous diagnostic significance for elucidating the etiopathogenesis of equine placentitis. As described above, many infectious agents ascend through the cervix to cause a focally extensive placentitis that originates near the cervical star. One exception is Leptospira spp., which characteristically produce a diffuse placentitis with numerous spirochetes demonstrated with special silver stains, particularly in the stroma.(1) A second exception is nocardiaform placentitis, caused by several genera of gram-positive, branching, filamentous actinomycetes (i.e. Crossiella equi, Streptomycin sp., Amycolatopsis sp.), which is typically localized to the cranial uterine body and entrance to the uterine horns and does not communicate with the cervical star.(4)

Finally, the conference moderator noted that syncytia and focal areas of mineralization are normal findings in the equine chorioallantois, but may increase in pathologic conditions. Other normal components of the equine placenta that may be confused with lesions were reviewed, including amniotic plaques, hippomanes, chorioallantoic pouches, allantoic pouches, and the yolk sac remnant.

References:

2. Hong CB, Donahue JM, Giles Jr. RC, Petrites-Murphy MB, Poonacha KB, Roberts AW, Smith BJ, Tramontin RR, Tuttle PA, Swerczek TW: Equine abortion and stillbirth in central Kentucky during 1988 and 1989 foaling seasons. J Vet Diagn Invest 5:560-566, 1993

3. Mahaffey LW and Adam NM: Abortions associated with mycotic lesions of the placenta in mares. J Am Vet Med Assoc 144:24-32, 1964

4. Schlafer DH, Miller RB: Female genital system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, pp. 507-509. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007