Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The disease affects a wide variety of mammals.(3) In North America, histoplasmosis is often diagnosed in the Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri River areas. The disease is mostly non-contagious in humans, dogs, cats, swine, horse, wild animals, and cattle. In companion animals, it is most often found in dogs and less frequently in cats.(7) True rate in companion animals is difficult to measure due to subclinical infections.(2) The infection is initiated by inhalation or ingestion of dust from soil. The majority of infections occur without signs and lesions, whereas when infection becomes clinically apparent, it is disseminated, and always fatal.(7) It is known now that in humans and lower animals, an acute, nonfatal form is more prevalent than the disseminated, fatal, rare form. The infection is connected to common environmental source rather than contagion from host to host.(3)

The genus Histoplasma, besides the three conventionally accepted species (capsulatum, duboisii, and farciminosum), was reported to have eight clades from different geographic regions, suggesting that genetically distinct geographical populations exist.(1,4) Genetic polymorphisms in the same areas were 100% similar.(6) Histoplasma capsulatum is the cause of classic histoplasmosis worldwide. H. duboisii is the cause of African histoplasmosis and H. farciminosum is the cause of epizootic lymphangitis in horses. This is characterized by chronic indurative ulceration of the skin with enlargement of regional lymph nodes.(3)

When inhaled, the microconidia are able to reach the lower respiratory tract. The incubation period is usually 12-16 days, during which the microconidia transform into yeast phase and reproduce by budding. The yeast is phagocytosed by mononuclear phagocytes and replicates further inside the cell.(2) This route accounts for the infection in the cervical and bronchial lymph nodes, but the usual intestinal lesions were also suggested to occur directly via ingestion, or by secondary infections like in the case of many other organs. The latent infections might persist without causing illness for months to years in different species. The signs of advanced disease include diarrhea, pyrexia, emaciation, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, a lymphadenopathy, and a nonregenerative, normochromic, normocytic anemia. In later stages the leukocyte counts are low, and toxic changes occur, such as the appearance of Doehle bodies. The disease usually causes lymphopenia and eosinopenia. Diagnosis can be made from fine-needle aspirations of liver, spleen, enlarged lymph nodes, bone marrow, or skin with microscopic examination. Cytologically, the organism can be detected in the cytosol of macrophages.(7)

If the spore dose is high or the hosts immune system is compromised, the infection can cause severe disease. The hosts cellular immune system, mainly involving cytokine-mediated macrophage killing, can control the infection. In some instances, the infection is not completely cleared and if immune suppression takes place, a reactivation can occur. The yeast form is more resistant to host defense due to its more invasive nature as it can severely impair phagocyte function. Moreover, the fungus can induce nonspecific anergy by overproducing interleukin-4, thus interfering with cellular immune response.(2)

In dogs, the primary disease in the lung appears as classic granulomas containing epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells carrying the organisms. After recovery, these regress to fibrocalcareous nodules present in the lungs for many years. Sometimes, similar lesions may be found in other organs.(3) Pathologically, the pulmonary lesions are 1-2 cm grayish nodules.

In the intestines, the lesions most frequently occur in the lower part of the small intestine as nodular thickenings of the mucosa in the lamina propria and submucosa that are the result of infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages. In rare instances, ischemic ulcerations might occur when the thickening is extreme.(7) In the intestine the lymph nodules and adjacent lymph nodes are greatly enlarged.(3)

Lymph nodes are firm and dry and greatly enlarged. In histological preparations, coalescing granulomas that replace portions of the cortex can be seen.(7) In lymph nodes, the predominant infiltrating cell type is histiocytic, with a less frequent plasma and lymphoid cell presence.(3) The spleen is also enlarged, grey, and firm, characterized by sinus expansion and colonization with macrophages containing the organism.

The liver becomes enlarged, and diffuse grey discoloration, due to capsular thickening without focal lesions, occurs.(7) Liver enlargement is caused by diffuse interlobular and intralobular proliferation of mononuclear phagocytes, leading to displacement of liver parenchyma, and causing liver dysfunction.(3)

The disease often involves the adrenal glands cortex, medulla, or both.(7) The involvement of adrenal glands in fatal cases is very striking, characterized by the replacement of the gland by macrophages. This phenomenon is most likely connected to the terminal stage of the disease, as it is not seen in animals sacrificed earlier.(3)

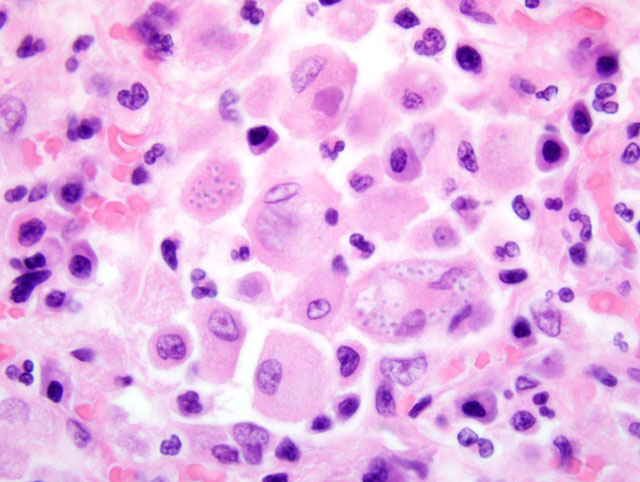

The organ enlargements are caused by intense infiltration of extensively proliferating monocytes and epitheloid macrophages carrying the organisms in their cytoplasm. The 2-4 um yeast bodies appear as basophilic dots surrounded by a halo (part of the cell wall) on sections stained with eosin and hematoxylin. The halo can be stained for bound glycogen, appearing as a ring, that helps distinguish the organism from cellular debris.(7) The cell wall can be stained selectively by PAS, Bauer, GMS or Gridley fungus method, resulting in a red or black ring appearance.(3)

When the organism is present in abundance, the staining is not necessary. However, in case of occult infection, isolation of organism from tissues must be done for diagnosis. Care must be taken during isolation to prevent inhalation of chlamydospores. The organism can only be held responsible for focal, nonprogressive lesions if it can be histologically demonstrated from tissue sections. For biopsy, enlarged lymph nodes or aspiration biopsy of bone marrow can be used.(7) Also, biopsies of tonsils and liver, which are places of extensive mononuclear phagocyte proliferation, or in certain cases, smears of circulating blood, can be used. Serologic tests are not reliable.(3)

Differential diagnosis is necessary from H. farciminosum by culturing the organism, as in tissue sections they appear the same, though the geographic and anatomical locations of the two diseases can reduce this difficulty. Differentiating from other protozoan and mycotic organisms can be done by immunologic staining techniques or can be based on morphological differences. Leishmania donovani contains a bar-shaped kinetoplast that is not present in histoplasmosis. Toxoplasma gondii is smaller and does not have rings when stained for bound glycogen. Blastomyces dermatitidis yeasts are larger and the budding base is different. Differentiating from Sporothrix schenckii requires immunologic staining. Some malignant neoplasms such as lymphoma can lead to uptake of tissue debris by macrophages; however, in these cases the absence of organism can differentiate from histoplasmosis.(3)

Public Health considerations: Animals and people traveling through endemic areas might be at risk. Direct host-to-host transmissions have not been reported. Also, transplanting kidneys of infected donor can carry the disease to the host.(2) In humans, the disease can affect people with AIDS or on immunosuppressive therapy. The disease can be the result of reactivation from a latent infection in both humans (8) and dogs.(5) (Reviewed in 1)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Green CE: Histoplasmosis. In: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, ed. Greene CE, 3rd ed., pp. 577-584. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2006

3. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed., pp. 519 - 522. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD, 1997

4. Kasuga T, White TJ, Koenig G, McEwen J, Restrepo A, Casta+â-¦eda E, Lacaz CDS, Heins-Vaccari EM, De Freitas RS, Zancop+â-¬-Oliveira RM, Qun Z, Negroni R, Carter DA, Mikami Y, Tamura M, Taylor ML, Miller GF, Poonwan N, Taylor J: Phylogeography of the fungal pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum. Mol Ecol 12:3383-401, 2003

5. Mackie JT, Kaufman L, Ellis D: Confirmed histoplasmosis in an Australian dog. Aust Vet J 75:362-3, 1997

6. Muniz MM, Pizzini CV, Peralta JM, Reiss E, Zancop+â-¬-Oliveira RM: Genetic diversity of Histoplasma capsulatum strains isolated from soil, animals, and clinical specimens in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, by a PCR-based random amplified polymorphic DNA assay. J Clin Microbiol 39:4487-94, 2001

7. Valli VEO: Hematopoietic system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 299-302. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

8. Wheat LJ, Kauffman CA: Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 17:1-19, vii, 2003