Signalment:

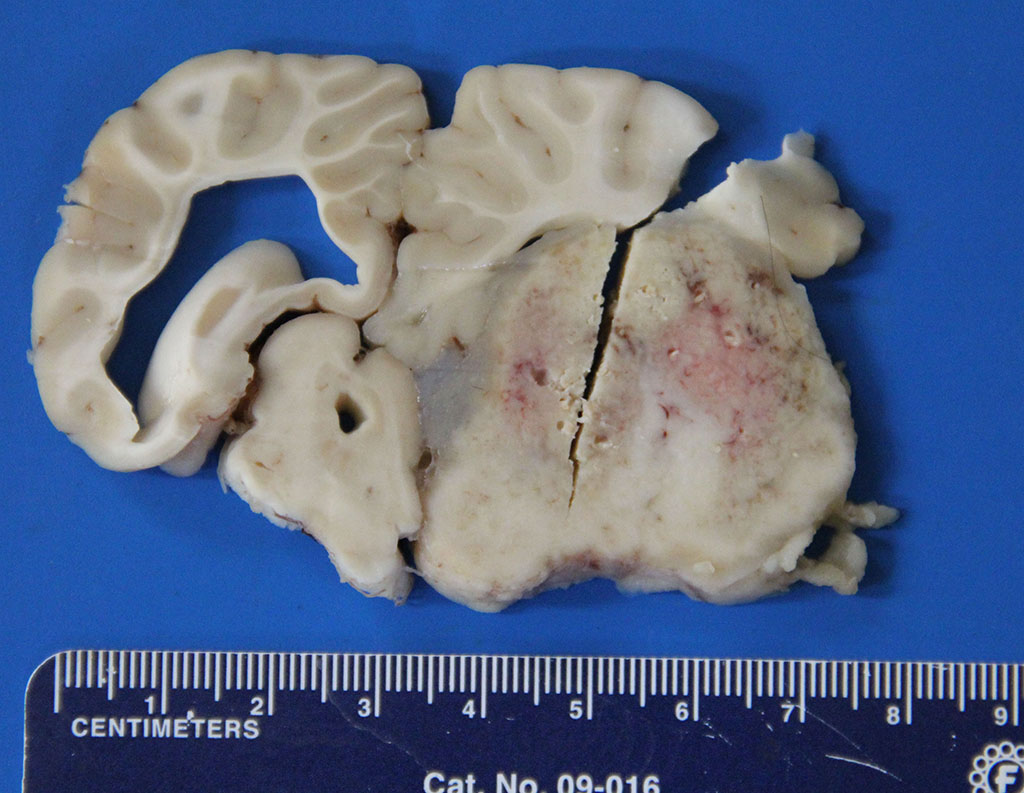

Gross Description:

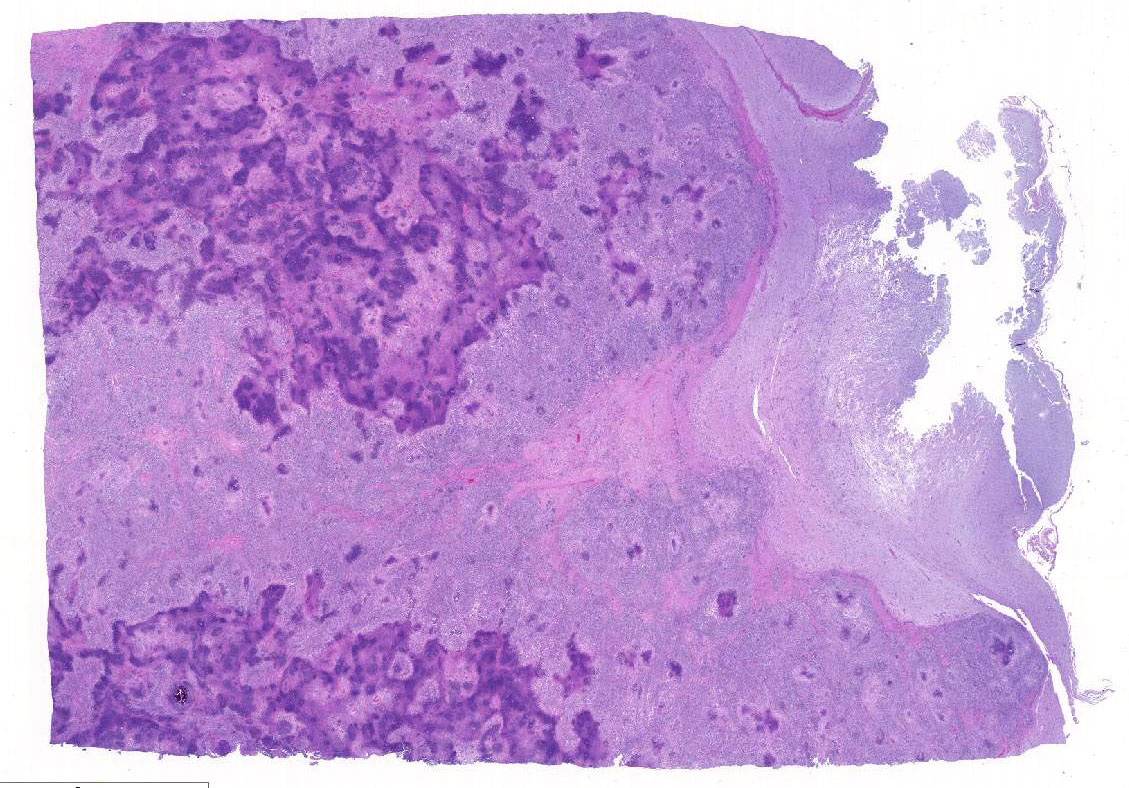

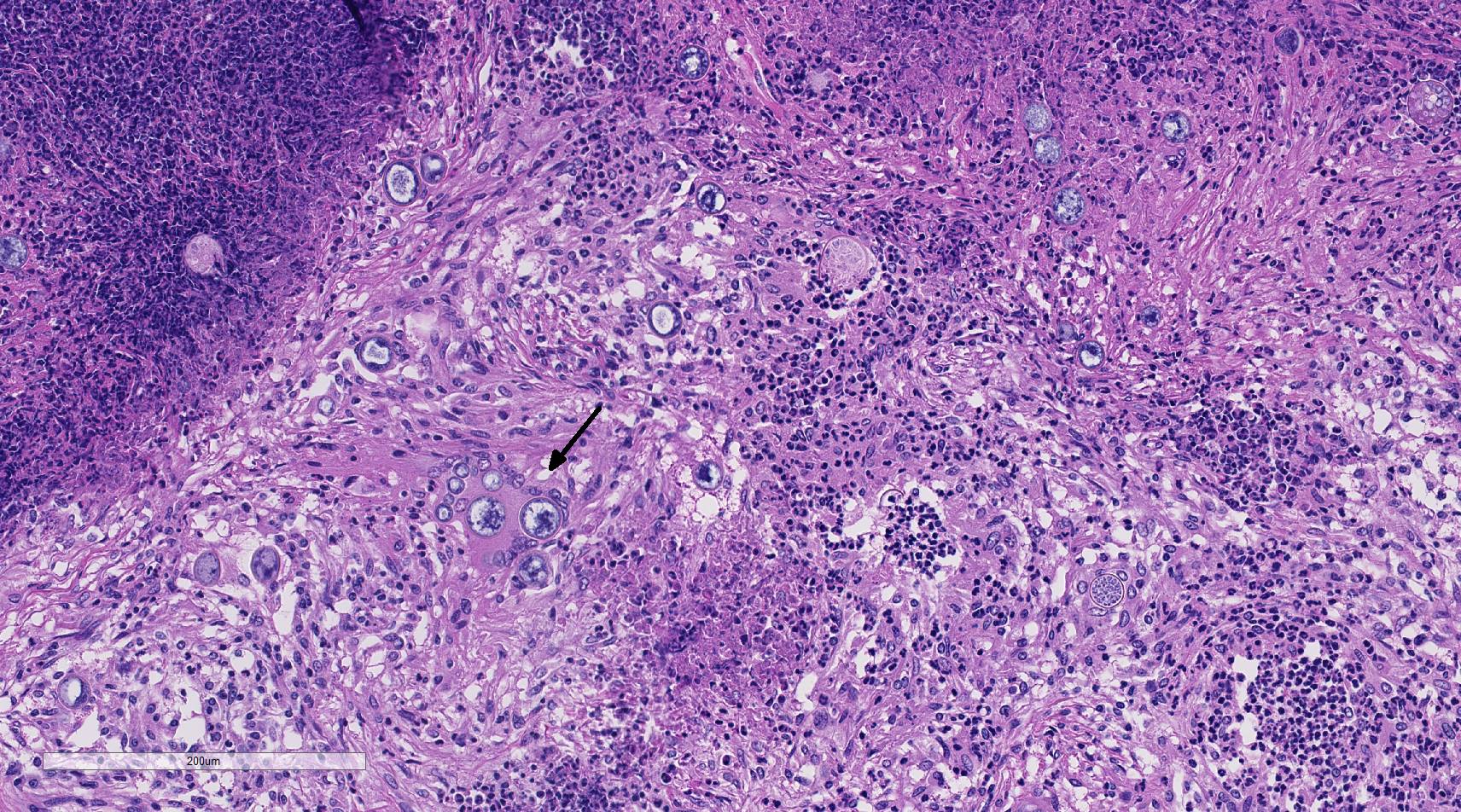

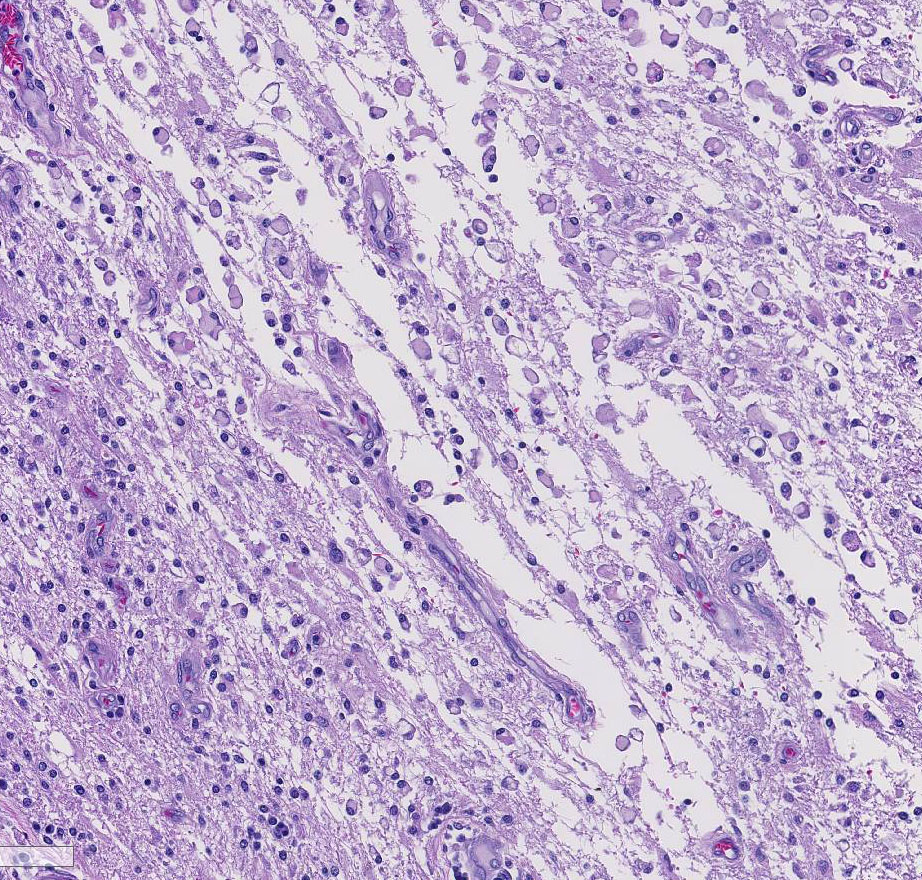

Histopathologic Description:

In other sections (slides not submitted), there is marked dilation of the lateral ventricle accompanied by multifocal, mild to moderate cuffing of subependymal blood vessels by plasma cells. One section of the lateral ventricle contains clumps of cellular debris, purulent exudate, and several small spherules. A moderate lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is present in the choroid plexus.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Fungal mycelia survive well in dry, hot conditions; grow after intense rainfall and release arthroconidia which are disseminated by the wind.3,9 Inhalation of airborne arthroconidia is the most common route of infection, although local traumatic inoculation has been associated with cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions. 3 The arthroconidia migrate to bronchi and alveoli and transform to yeast forms (immature spherules) of 10-20 um in diameter. As spherules mature they enlarge up to 100 um in diameter and are surrounded by a double contour, 4-5 um hyaline wall. Spherules undergo endosporulation forming numerous uninucleated endospores 2-5 um in diameter. Mature spherules rupture to release endospores that form new spherules in tissue or mycelia if released to the environment.3,14 Dissemination to other organs is through blood or lymphatics, and fungi are believed to reach the central nervous system through leukocytic trafficking and hematogenous spread from primary sites of infection. 3,12

Three main virulence mechanisms by which Coccidiodes spp. survive in host environment have been described.12 These include:

- 1. Production of dominant spherule outer wall glycoprotein (SOWgp) which modulates the host immune response resulting in compromised cell-mediated immunity

- 2. Depletion of SOWgp presentation on endospore surface preventing host recognition of the pathogen

- 3. Induction of host arginase 1 (decreased nitric oxide production) and coccidial urease which contribute to tissue damage at sites of infection.

Although the spherule form shed from lesions is not readily infectious, arthroconidia from mature cultures are easily aerosolized and are highly infectious. 14 As such, Coccidioides immitis is designated as Biosafety Level 3, and is classed as a select agent of bioterrorism in the United States due to its high virulence and infectious nature. 6

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The most common presentation of disseminated disease is lameness due to osteomyelitis.9,10 This typically occurs late in the disease and is characterized by osteolytic granulomas surrounded by proliferative new bone growth. Painful draining tracts in the overlying skin, palpable bone swelling, and enlarged and reactive regional lymph nodes are additional signs of disseminated disease.3 However, generalized lymphadenopathy is uncommon in this disease.3,9 Other clinical signs of disseminated disease are variable and are usually dependent on the organ infected. Animals with central nervous system (CNS) disease, such as this case, typically have seizures, progressive ataxia, and are comatose in severe cases. Other organs affected include: eyes, liver, spleen, kidney, and testes.3,9 Abortion has also been reported in both horses and an alpaca in Southern California. 5

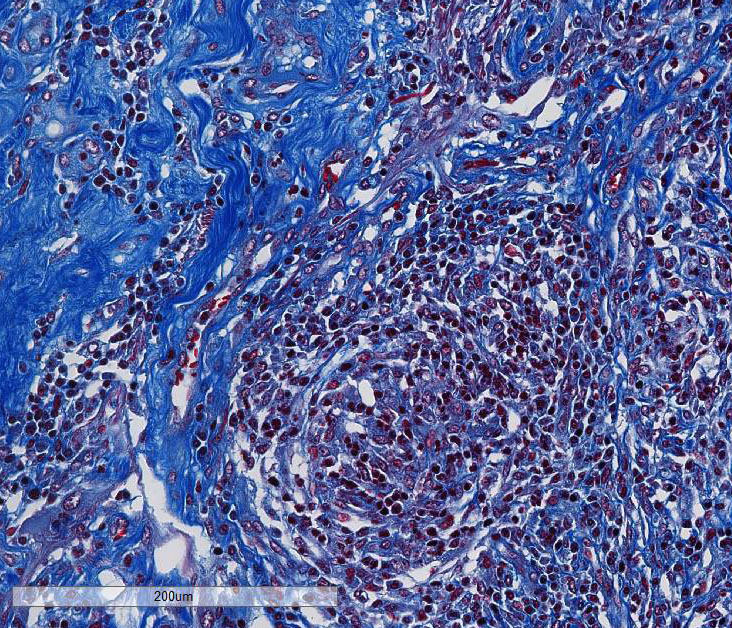

This case generated enthusiastic debate among conference participants regarding whether the profound pyogranulomatous inflammation effacing 90% of the histologic section originated from the cerebrum or the meninges. Participants favoring cerebral origin argued that the cerebrum is lost and replaced by an astrocytic scar with spindled and palisading epithelioid macrophages. Participants favoring meningeal origin noted that the spindled cells are birefringent and likely represent collagen and fibrous connective tissue deposition secondary to chronic pyogranulomatous inflammation. A Massons trichrome stain revealed abundant blue staining collagen within the granuloma. Given that fibrocytes are not a normal component of the neuropil, it is likely that fibrocytes penetrated into the granuloma from the adjacent meninges. The granuloma was also diffusely immune-negative for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), supporting a meningeal origin of the granuloma rather than an astrocytic scar in the cerebrum.

Several conference participants also noted a focal area of cavitary necrosis within the cerebrum adjacent to the pyogranuloma. This is likely due to thrombosis of a vessel adjacent to the large granulomatous nodule, creating an infarct in the section of the cerebrum. Unfortunately, none of the conference participants noted vascular thrombi within their tissue sections. The vascular thrombi may be out of the plane of section.

References:

2. Ajithdoss DK, Trainor KE, Snyder KD, Bridges CH, Langohr IM, Kiupel M, Porter BE. Coccidioidomycosis presenting as a heart base mass in two dogs. J Comp Pathol. 2010; 145:132-137.

3. Caswell JL, Williams KJ: Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 583-584.

4. Coster ME, Ramos-Vara J, Vemulapalli R, Stiles J, Krohne SG. Coccidioides posadasii keratouveitis in a llama (llama glama). Vet Ophthalmol. 2010; 13:53-57.

5. Diab S, Johnson S, et al. Case report: abortion and disseminated infection by Coccidioides posadasii in an alpaca (Vicugna pacos) fetus in Southern California. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2013; 2:159-162.

6. Dixon DM. Coccidioides immitis as a select agent of bioterrorism. J Appl Microbiol. 2001; 91:602-605.

7. Fauquier DA, Gulland FMD, Trupkiewicz JG, Spraker TR, Lowenstine LJ. Coccidioidomycosis in free-living California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) in Central California. J Wildl Dis. 1996; 32:707-710.

8. Fisher MC, Koening GL, White TJ, Taylor JW. Molecular and phenotypic description of 22 Coccidioides posadasii sp. previously recognized as the nonCalifornian population of Coccidioides immitis. Mycologia. 2002; 94:73-84.

9. Graupmann-Kuzma A, Valentine BA, Shubitz LF, Dial SM, Watrous B, Tornquist SJ. Coccidioidomycosis in dogs and cats: a review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2008; 44:226-235.

10. Higgins JC, Leith GS, Pappagianis D, Pusterla N. Treatment of Coccidioides immitis pneumonia in two horses with fluconazole. Vet Record. 2006; 159:349-351.

11. Hoffman K, Videan EN, Fritz J, Murphy J. Diagnosis and treatment of ocular coccidioidomycosis in a female captive chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) a case study. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007; 1111:404-410.

12. Hung C-Y, Xue J, Cole GT. Virulence mechanisms of Coccidioides. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007; 1111:225-235.

13. Reidarson TH, Griner LA, PappagianisD, McBain J. Coccidioidomycosis in a bottlenose dolphin. J Wildl Dis. 1998; 34:629- 63, 1998.

14. Shubitz LF, Dial SM. Coccidioidomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2005; 220:226.

15. Shubitz LF, Dial SM, Galgiani JN. T-lymphocyte predominance in lesions of canine coccidioidomycosis. Vet Pathol. 2010; 45:1008-1011.

16. Terio KA, Stalis IH, Allen JL et al. Coccidioidomycosis in Przewalskis horses (Equus prewalskii). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2003; 34:339-345.

17. Tofflemire K, Betbeze C. Three cases of feline ocular coccidioidomycosis: presentation, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment. Vet Ophthalmol. 2010; 13:166-172.