Signalment:

Gross Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

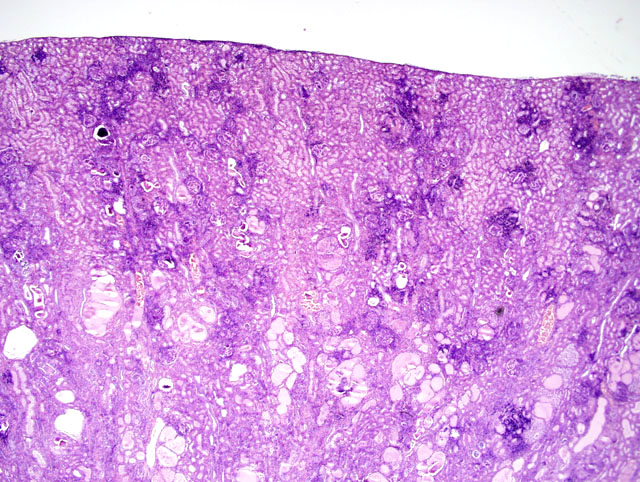

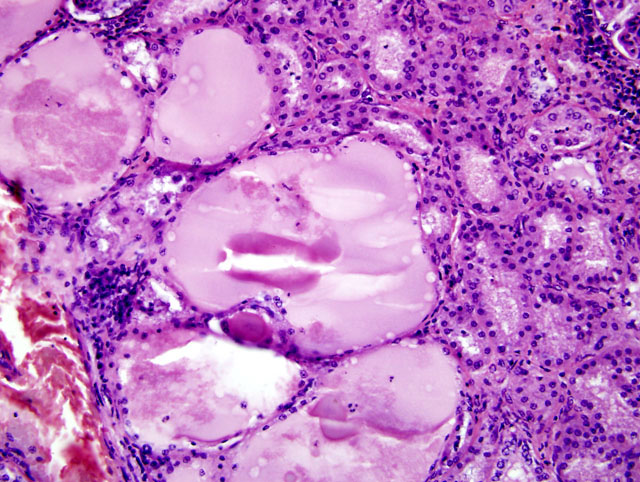

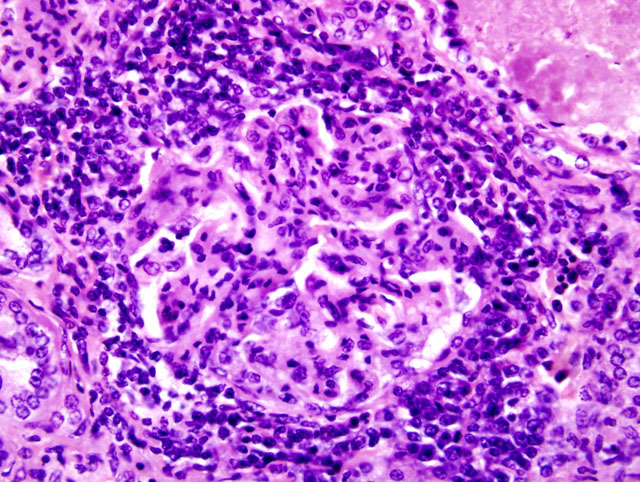

2) Kidney, tubular ectasia (Fig. 3-2), diffuse, severe with glomerulosclerosis and membranous glomerulopathy with mesangial proliferation (Fig. 3-3), multifocal, moderate.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The relationship between malaria and renal disease has been long understood and was first described in a malarial patient with edema in 1905.1 There are two major renal syndromes associated with malarial infection. The first is a chronic, progressive glomerulopathy most common in children in Africa with P. malariae infection and the other an acute renal failure associated with falciparum malaria in Southeast Asia, India, and sub-Saharan Africa.2 Falciparum malaria can also be associated with a severe disease in humans characterized by intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinurea, acute tubular necrosis, and renal failure and is termed blackwater fever.

Although there are differences between P. malariae and P. falciparum infection in humans, the histological changes within the kidney of experimentally infected owl monkeys can be similar. Histological features include glomerular hypercellularity, infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and thickening of the glomerular basement membrane and mesangium.1,5,6 Immunofluorescent microscopy reveals IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 within the mesangium and along the basement membrane and Plasmodium sp. antigens and corresponding antibodies.1,5,6 Interstitial inflammation is a common finding in inoculated monkeys.

A condition exists that complicates studying malarial associated renal disease and nephrotic syndrome in owl monkeys. Owl monkeys commonly have spontaneous renal disease.1,3,8 Renal disease such as glomerulonephropathies and interstitial nephritis are some of the most common causes of death in owl monkeys. The cause is unknown, but it has been speculated that it may be due to immune responses to infectious agents in their natural habitat of Central and South America. Histologically, lesions are characterized by increased mesangium, glomerulosclerosis, and interstitial nephritis with lymphocytic, eosinophilic, and plasma cell infiltration.1,3

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Diagnosis may be made on a blood smear stained with Giemsa or Wright-Giemsa stains. Hemazoin, a brownish malarial pigment formed from the incomplete catabolism of hemoglobin by the parasite7, can be seen in Kupffer cells of the liver, within macrophages in the bone marrow, and in the red pulp of the spleen.10

The life cycle4, 9 consists of an infected mosquito feeding on a susceptible host injecting sporozoites into the host circulation. These sporozoites invade hepatocytes by binding hepatocyte receptors for the serum proteins thrombospondin and properdin.9 They develop in hepatocytes to form schizonts that release up to 30,000 merozoites when the hepatocytes rupture. Merozoites enter erythrocytes by binding a parasite lectinlike molecule to sialic residues on glycophorin molecules on the surface of red blood cells.9 There, they reside within a parasitophorous vacuole, until it enlarges into a trophozoite stage, divides into schizonts containing 24 or more merozoites, and lyses the erythrocyte to then infect other RBCs. A few merozoites will develop into gametocytes (both micro- and macrogametocytes) which are taken up by a mosquito during a blood meal. Within the mosquito, the gametocytes develop into gametes, forming a motile zygote. Through repeated nuclear divisions, the oocyst ruptures releasing sporozoites into the hemolymph, where they then migrate to the salivary gland for injection into a susceptible vertebrate host.

References:

2. Barsoum RS: Malarial acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 11:2147-2154, 2000

3. Chalifoux LV, Bronson RT, Sehgal P, Blake BJ, King NW: Nephritis and hemolytic anemia in owl monkeys (Aotus trivirgatus). Vet Pathol 18(S6):23-37, 1981

4. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues, pp 65-66. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology, Washington, DC 1998

5. Hutt MSR, Davies DR, Voller A: Malarial infections in Aotus trivirgatus with special reference to renal pathology. Br J Exp Path 56:429-438, 1975

6. Iseki M, Broderson JR, Pirl KG, Igarashi I, Collins W, Aikawa M: Renal pathology in owl monkeys in Plamodium falciparum vaccine trials. Am J Trop Med Hyg 43:130-138,1990

7. Jones TC, Hunt RD, and Norval WK: Veterinary Pathology, pp. 590-593. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD 1997

8. Roberts JA, Ford EW, Southers JL: Urogential system. In: Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research, Diseases, eds. Bennett BT, Abee, CR, Henrickson R, pp. 311-333. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 1998

9. Samuelson J: Infectious diseases. In: Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, eds. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, 6th ed., pp. 389-391. WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, PA 1999

10. Toft JD, Eberhard ML: Parasitic diseases. In: Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases, ed. Bennett BT, Abee CR, Henrickson R, pp.124-126, 249. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 1998