Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 16

January 24th, 2018

CASE III: H15-0067L (JPC 4067142).

Signalment: Unknown age, male, Bilby, Macrotis lagotis, marsupial.

History: A captive young adult male bilby (Macrotis lagotis) was euthanized at a wildlife park following the onset of severe lethargy and was subsequently presented to the anatomic pathology service at Murdoch University Veterinary Hospital for necropsy examination. Approximately two months prior, the bilby was captured for an annual health check. He was healthy and weighed 2098 grams. On that day he was transferred to a neighboring enclosure which contained 10 other bilbies, including one young male and nine adult and sub-adult females. Approximately seven weeks later, the bilby became lethargic and was recaptured. He weighed 1630 grams. He was isolated and euthanized three days later following no improvement. A zoo keeper was bitten during capture.

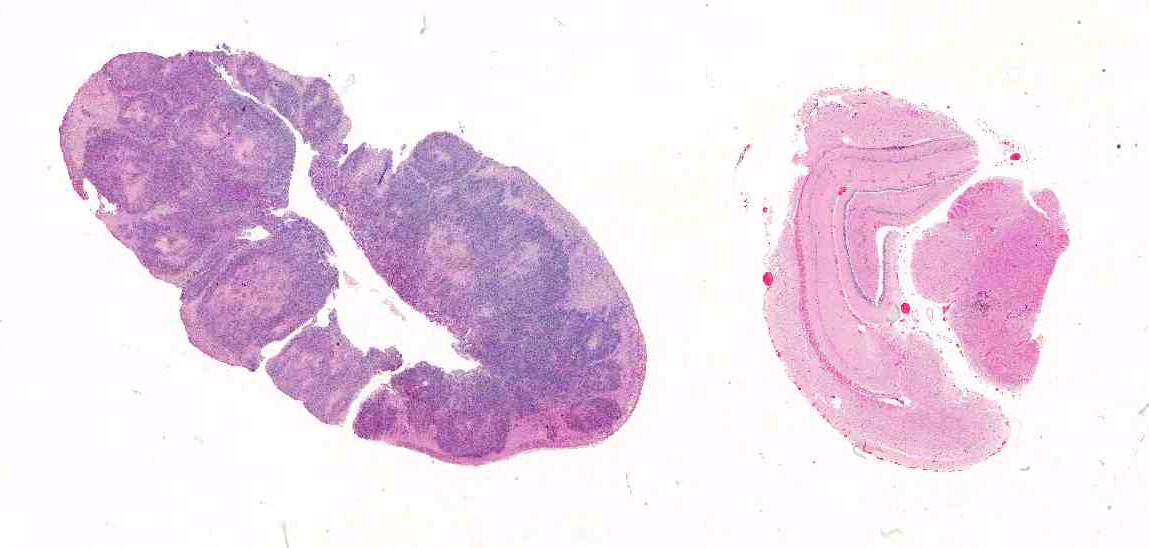

Gross Pathology: On gross examination, the bilby was emaciated with a focal circular, ulcerated skin lesion on the dorsal tail base. Dozens of variably sized, poorly demarcated, red to tan nodules were present throughout the lungs and kidneys. The adrenal glands were markedly enlarged, pale tan and soft with loss of corticomedullary distinction.

Laboratory results: Samples of aseptically collected lung and spleen were stored at 4°C prior to submission for fungal culture. Tissue cultures isolated Sporothrix schenckii demonstrating thermal dimorphism. At 26°C the isolates were expanding, crumbly and grey in color and at 36°C an atypical yeast-like organism was identified. Microscopically, organisms were characterized by clavate conidia arranged predominantly terminally on erect conidophores attached by fine denticles. Dematiaceous sessile conidia were also observed. Subsequent sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions confirmed the isolate as Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato.

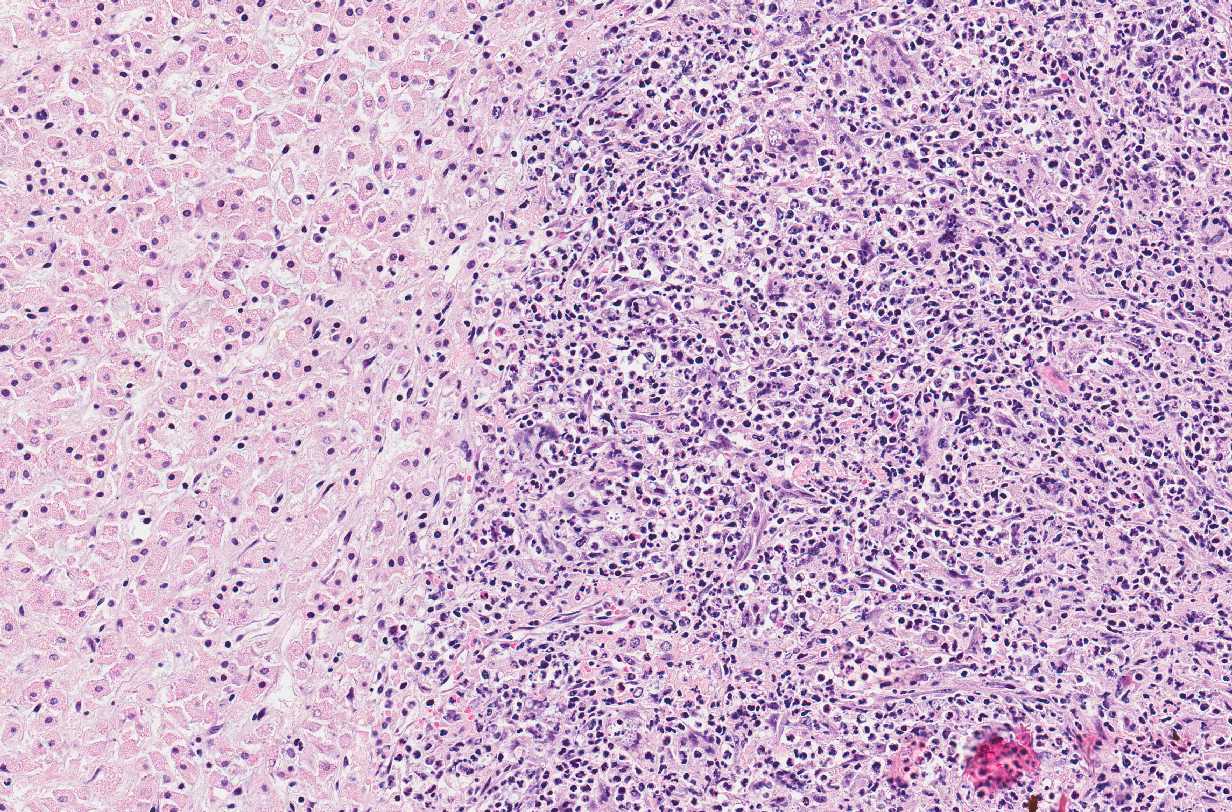

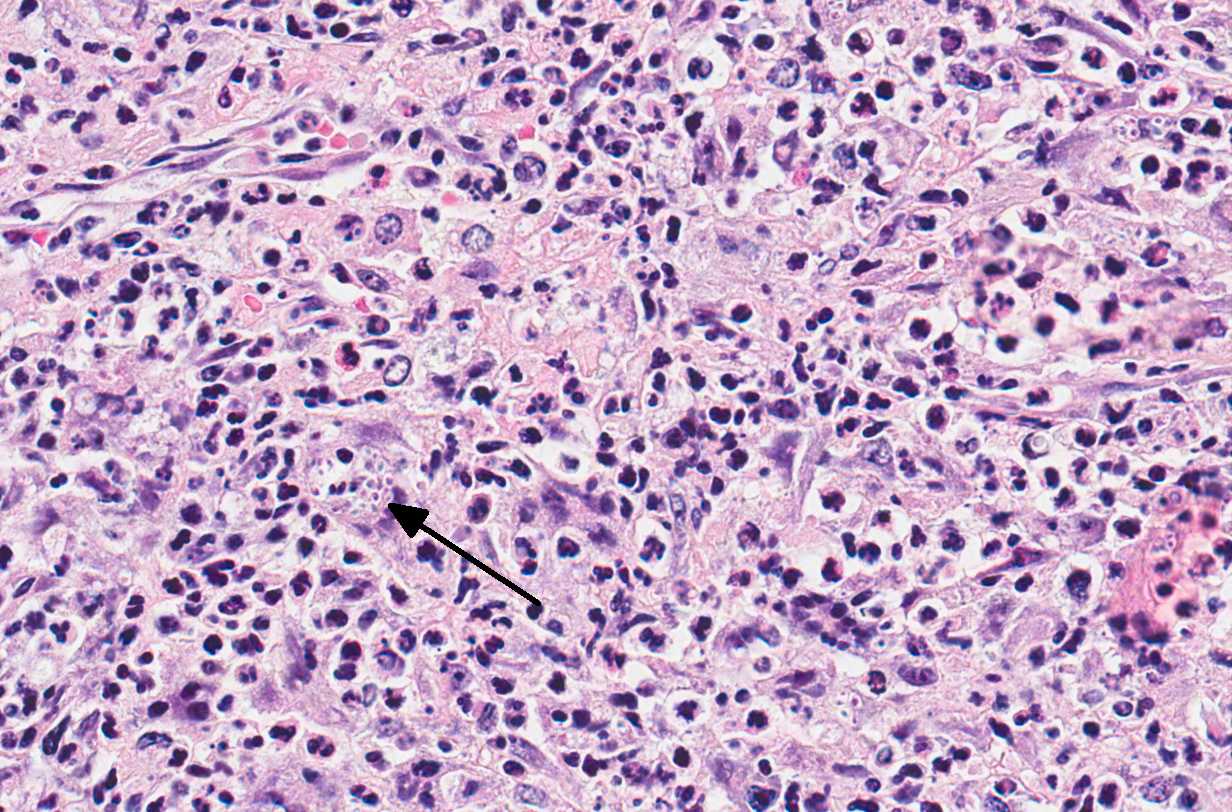

Microscopic Description: Adrenal glands: Diffusely effacing the normal medullary architecture and extensively infiltrating and effacing over 90% of the cortex, are large numbers of degenerate neutrophils and epithelioid macrophages admixed with moderate numbers of multinucleate giant cells, and large amounts of eosinophilic and karyorrhectic debris (necrosis). Admixed are frequent pleomorphic 2-15 μm diameter yeast. These organisms are predominately intracellular within the cytoplasm of macrophages and multinucleate giant cells, but are also present in fewer numbers extracellularly within areas of necrosis. Yeasts are round, oval or elongate (cigar-shaped) and larger yeast (10-15 μm diameter) are round to oval with rare narrow-based budding. Yeasts are sometimes surrounded by a clear thin halo and/or a slightly refractile clear cell wall, and stain intensely positive with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). The smaller forms (2-9 μm diameter) are elongate, cigar-shaped to oval and stain intensely positive with PAS and are also Gram positive.

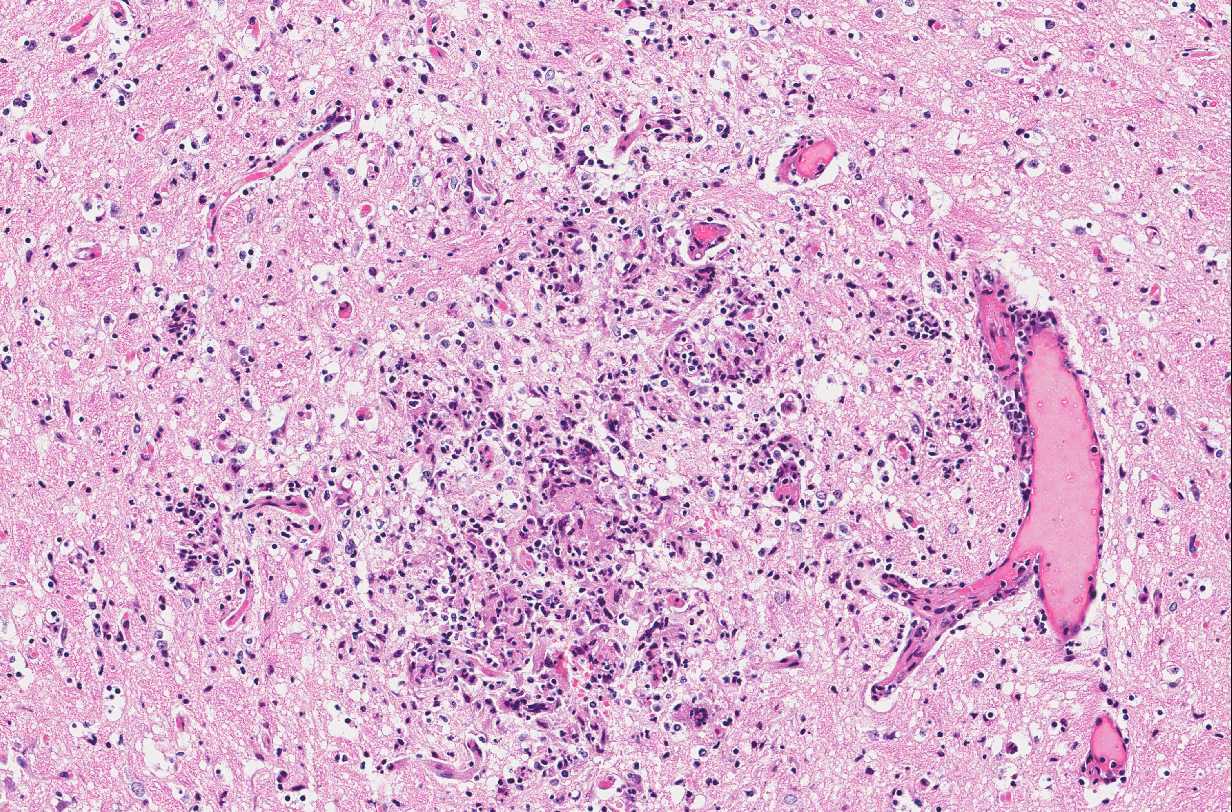

Brain: In multiple regions of brain, including the cerebrum, hippocampus and midbrain, the neuropil and leptomeninges are disrupted by multifocal to coalescing, randomly distributed foci of pyogranulomatous inflammation as previously described. Low numbers of the previously described fungal yeast are present scattered throughout the inflammatory foci. Mildly increased numbers of glial cells are present immediately surrounding these inflammatory foci.

Similar inflammatory foci are also present within the kidneys, lungs, testes, lymph nodes, heart, liver, spleen, salivary glands and tail wound.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Adrenal glands: Severe, regionally extensive, subacute, pyogranulomatous and necrotizing adrenalitis with numerous intrahistiocytic and extracellular fungal yeast.

Brain: Moderate, multifocal to coalescing, random, subacute, pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis with occasional intrahistiocytic and extracellular fungal yeast and mild gliosis.

Contributor’s Comment: The histological and fungal culture findings are consistent with disseminated sporotrichosis, an uncommon fungal disease of humans and animals which, outside of Brazil, is usually caused by the fungus Sporothrix schenkii. Gene sequencing of isolates from Brazil have shown the most common species as S. brasiliensis, with S. globosa, S. albicans, S. luriei and S. Mexicana also isolated.1,5 Sporothrix spp. are thermally dimorphic, cosmopolitan fungi found in soil, hay and decaying plant matter.

Based on the size and pleomorphic nature of the yeast, Sporothrix schenckii was strongly suspected following initial microscopic evaluation; however, other yeast that can appear morphologically similar include Cryptococcus spp. and Blastomyces dermatitidis (see table below for summary of common fungal yeast pathogens).

Given the presence of the organism within the chronic skin wound on the tail base, the most likely route of infection in this case was considered to be either wound inoculation or direct inoculation from a penetrating wound, with subsequent dissemination via hematogenous or lymphatic spread to numerous internal organs.

Although multiple cases of fungal disease have been described in a variety of native Australian marsupials and monotremes, to our knowledge this is the first reported case of sporotrichosis in a native Australian marsupial. Trichophyton spp. and Microsporum spp. have been described as the cause of dermatophytosis in both native Australian macropods and koalas. Mucor amphibiorum causes significant morbidity and mortality in the platypus, with severe ulcerative dermatitis, occasional spread to underlying muscle and dissemination to other organs. Candida spp. have been reported to cause gastrointestinal infections in macropods and koalas and Cryptococcus gatii and C. neoformans var grubii have been associated with cryptococcal meningitis, pulmonary and disseminated cryptococcosis in a number of macropod species, koalas and a single dusky antechinus (Antechinus swainsonii).

In the veterinary literature, sporotrichosis has been reported in a variety of animals. Cats are the most commonly affected domestic species; however, cases in dogs, horses, cattle, pigs, fish, rodents and armadillos have also been reported.6,12 In cats, sporotrichosis typically presents as ulcerated, nodular cutaneous lesions, most commonly on the head and ears. Respiratory mucosal involvement is common; ascending lymphangitis and dissemination are reported less frequently.8,13 Disseminated disease is rare in all species, with human cases occurring most often in immunocompromised patients. In cats, however, it usually occurs in the absence of immunosuppression.8,11,13 Feline sporotrichosis is an important source of zoonotic sporotrichosis in humans, with cases in Brazil associated with bites and scratches from infected domestic cats (Felis catus). S. schenkii has been isolated from the nail beds of healthy cats.4 Human infections resulting from bites or scratches from rodents, armadillos, and a single opossum have also been reported.3,12 In this case, zoonotic infection did not occur following the bilby bite.

Table 1. Summary of common fungal yeast pathogens.10

|

Features |

Sporothrix spp |

Cryptococcus neoformans |

Blastomyces dermatidis |

Coccidioides immitis |

Histoplasma capsulatum |

Histoplasma farciminosum |

|

|

Histopathology |

|||||||

|

Tissue morphology Budding |

Pleomorphic cigar shaped yeast cells Narrow base |

Oval yeast cells with prominent thick capsule Narrow base |

Thick walled yeast cells Broad base & unipolar |

Spherules containing endospores |

Oval yeast cells within macrophages Narrow base |

Oval yeast cells within macrophages Narrow base |

|

|

Size (diameter) |

3-6 μm |

4-8 μm |

8-10 μm |

Spherules 10-80 μm, endospores 2-5 μm |

2-5 μm |

2-5 μm |

|

|

Staining |

PAS, silver stains, small forms: Gram positive |

PAS, silver stains, capsule: mucicarmine |

PAS, silver stains |

PAS, silver stains |

PAS, silver stains |

PAS, silver stains |

|

|

Epidemiology & clinical disease |

|||||||

|

Disease Species most affected Environmental habitat Geographical distribution Site of lesions Route of infection |

Sporotrichosis Horses, cats, dogs & humans Decaying vegetation, soil, moss Worldwide, mainly tropical and subtropical Lymphocutaneous, occasional dissemination Traumatic implantation |

Cryptococcosis Cats horses and humans Soil enriched with bird faeces & Australian red gum trees Worldwide Nasal cavity, lungs, brain, eye, skin Inhalation |

Blastomycosis Dogs and humans Acidic soil rich in organic matter North America, India and the Middle east Lungs with metastasis to skin and other tissues Usually inhalation |

Coccidiomycosis Dogs, horses and humans Arid or semi-arid soil in low-lying areas Southwestern USA, Central and South America Lungs with metastasis to bones Usually inhalation |

Histoplasmosis Dogs, cats and humans Soil enriched with bird and bat faeces Endemic to Mississippi and Ohio river valleys with sporadic cases in other countries Lungs with occasional dissemination Inhalation |

Epizootic lymphangitis Equidae Soil Africa, the Middle East and Asia Skin, lymphatic vessels and nodes Traumatic implantation |

|

|

Mycological characteristics |

|||||||

|

Fungal culture |

Dimorphic 25°C mould colonies white to black/brown, wrinkled and leathery; conidia pear shaped arranges in rosettes on conidiophores 35-37°C yeast colonies cream to tan |

37°C mucoid colonies with capsules, urease activity; brown colonies on birdseed agar |

Dimorphic 25-35°C mould colonies white and cottony producing pear shaped conidia borne on conidiophores or hyphae 37°C yeast colonies cream to tan, wrinkled and waxy |

25-30°C mould colonies shiny moist and grey to white and cottony; septate hyphae with barrel shaped arthrospores separated by empty cells |

Dimorphic 25-30°C white to buff colonies with cottony aerial hyphae; septate hyphae bear small conidia and sunflower-like macroconidia 37°C yeast colonies cream to tan, round and mucoid |

Dimorphic similar to H. capsulatum |

|

JPC Diagnosis:

- Adrenal gland: Adrenalitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, severe with numerous intracellular and extracellular yeasts, Bilby (Macrotis lagotis), marsupial.

- Brain, diencephalon: Encephalitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal, moderate with rare intracellular yeasts.

Conference Comment: Sporotrichosis is a subacute to chronic disease of animals and humans caused by fungi of the Sporothrix spp. of which Sporothrix schenckii is the most common. S. schenckii is a dimorphic fungus, meaning it is in its mycelial form at room temperature and when at 37 °C (body temperature) it develops into the yeast form. Microscopically, the yeast form is oval to cigar-shaped with a thin refractile cell wall, 2-6 um in diameter by 2-10 um in length, exhibit narrow based budding, and may intracellular (within multinucleated giant cells or macrophages) or extracellular. Like many other types of fungi, Sporothrix elicits a diffuse or nodular pyogranulomatous response. When cutaneous, the epidermis is often hyperplastic or ulcerated and often accompanied by fibrosis. In some cases, yeasts are surrounded by Splendore-Hoeppli material or asteroid bodies, but this is not pathognomonic for sporotrichosis and can be seen when there is antigen-antibody complex formation surrounding other organisms or foreign objects.2,9

Sporotrichosis has been reported in cats, dogs, horses, mules, donkeys, cattle, goats, swine, camels, and humans. As discussed in this case, sporotrichosis carries a risk of zoonotic transmission, and the most common route is from cats to humans.2 Disease is more common in cats, horses, and dogs living in temperate and tropical zones; particularly in intact male outdoor cats and hunting dogs. Infection is acquired via puncture wounds, and pulmonary infection occurs rarely via inhalation of spores. Sporothrix spores are quite hardy and can survive for months or years in soil, vegetation, and wood. The human form of disease is termed “rose handler’s disease” which illustrates that point.2 Clinically, there are three forms of sporotrichosis: (1) Primary cutaneous form; (2) Cutaneous-lymphatic form; and (3) Extracutaneous or disseminated form.9

The primary cutaneous form is most likely a result of strong host immunity and results from puncture wounds with the organism confined to the point of entry. This form tends to be chronic and clinically appears as multiple scattered raised, alopecic, ulcerated or crusted nodules along the head or distal extremities. Infected cats can spread the organism around their own epidermis through autoinoculation by grooming.9

The cutaneous-lymphatic form is the most common form in horses and humans and involves the skin and subcutis with spread through associated lymphatics. Affected lymphatic vessels become thickened and rope-like, regional lymph nodes are enlarged, and often nodules break open resulting in oozing sores. In this form, lesions are often along the proximal forelimbs, chest, and thighs.9

Finally, the extracutaneous or disseminated form occurs most frequently in cats and may involve a single extracutaneous tissue or multiple organs. This form develops often as a sequela to cutaneous-lymphatic infection or following inhalation of spores. In affected cats, no immunosuppressive factors have been identified and it is unclear what causes Sporothrix to disseminate. Clinically, affected cats are febrile, depressed, and anorexic.9

Microscopically, the cigar-shaped yeast is characteristic, and can be readily identified using standard fungal stains (GMS or PAS) or Gram stain (gram-positive),2 but there are times when the cigar-shaped form is not present. In those cases, common differentials would include Cyptococcus neoformans or Histoplasma capsulatum. However, Cryptococcus neoformans can be much larger (up to 20um) with a very thick 2um capsule that stains with mucicarmine, and Histoplasma capsulatum is always intracellular.9

Contributing Institution:

http://www.murdoch.edu.au/Services/Veterinary-Hospital/About-us/Services/Pathology-and-Clinical-Pathology/

References:

- Alves SH, Boettcher CS, de Oliviera DC, et al. Sporothrix schenckii associated with armadillo hunting in Southern Brazil: epidemiological and antifungal susceptibility profiles. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2010;43:523-525.

- Chandler FW, Kaplan W, Ajello L. Sporotrichosis. In: Color Atlas and Text of the Histopathology of Mycotic Diseases. Chicago, IL: Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc.; 1980: 112-115.

- da Rosa ACM, Scroferneker ML, Vettorato R, et al. Epidemiology of sporotrichosis: a study of 304 cases in Brazil. Journal of the Americal Academy of Dermatology. 2005;52:451-459.

- de Souza L, Nascente P, Nobre M, et al. Isolation of Sporothrix schenkii from the nails of healthy cats. Brazilian Journal of Mycology. 2006;37:372-374.

- Gremiao IDF, Menezes RC, Schubach TMP, et al. Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Medical Mycology. 2015;53:15-21.

- Ladds P. Pathology of Australian Native Wildlife. Collingwood, AUS: CSIRO Publishing. 2009:155-167.

- Lopez-Romero E, Reyes-Montes M, Perez-Torres A, et al. Sporothrix schenckii complex and sporotrichosis, an emerging health problem. Future Microbiology. 2011;6:85-102.

- Mata-Essayag S, Delgado A, Colella MT, et al. Epidemiology of sporotrichosis in Venezuela. International Journal of Dermatology. 2013;52:974-980.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 655-657.

- Quinn P, Markey B, Carter M, et al. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. 2010:235-245.

- Schubach A, de Lima Barros MB and Wanke B. Epidemic sporotrichosis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2008;21:129-133.

- Teixeira MM, de Almeida LGP, Kubitschek-Barreira P, et al. Comparative genomics of the major fungal agents of human and animal sporotrichosis: Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:943-964.

- Wenker CJ, Kaufman L, Bacciarini LN, et al. Sporotrichosis in a nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 1998;29:474-478.