Signalment:

Gross Description:

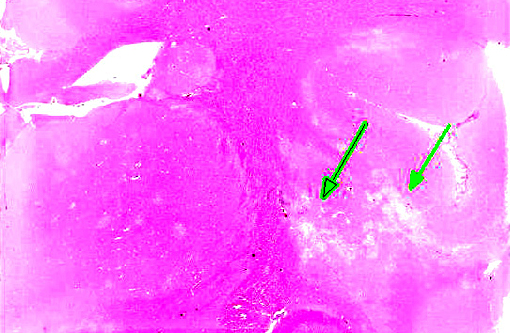

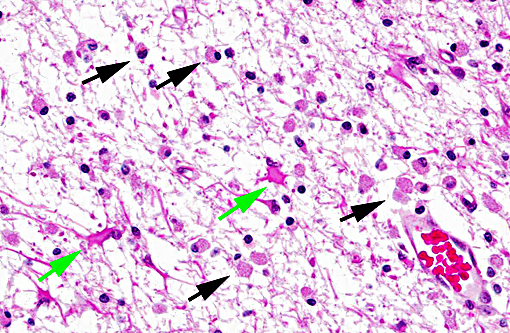

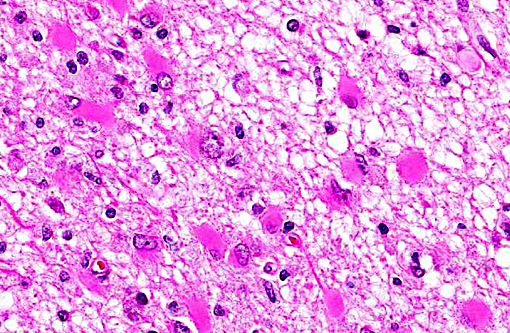

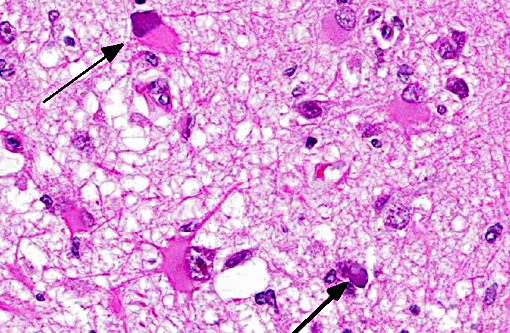

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Immunohistochemistry of brain sections for SV40 antigen revealed moderate to strong staining of astrocyte nuclei and nuclei of (presumably) oligodendroglia within the white matter of the cerebrum and the cerebellum. Luxol fast blue staining of cerebrum and cerebellum highlighted loss of myelin with minimal myelin particulates in gitter cells.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Polyomaviruses are small, double-stranded DNA viruses and have been identified in birds, rodents, nonhuman primates, and humans. They were named for their propensity to cause tumors in either their natural host or atypical host(s), typically in differentiated cells. Much like herpesviruses, infection by polyomaviruses in their natural hosts typically causes an asymptomatic, life-long infection. The polyoma virion is divided into early and late-coding regions. The early region codes T antigens, the late codes capsid proteins. Small (t) and large (T) transforming/tumor antigens are conserved across all polyomavirus species and these proteins are fairly well-characterized. The small t antigen is not necessary for productive infection in cell culture, but the large T antigen is essential for production of progeny virions. T antigen plays a role in DNA replication as well as tumorigenesis. Some polyomaviruses, including SV40, have additional T antigens.1

Simian virus 40 (SV40) is an endemic polyomavirus in captive and free-ranging macaques. Seroprevalence increases with age in socially-housed animals, and the majority of animals are seropositive by 1 year of age.(9) Infection does not cause lesions in immunocompetent animals, but immune-suppression, such as SIV infection or immunosuppressive drug regimens, allows reactivation of latent infections or primary infections to cause disease. Disease in immunosuppressed macaques can manifest as progressive multifocal leukoenceph-alopathy (PML), nephritis, or pneumonia.(6)

SV40 is of particular utility in research due to its comparative ease to grow in culture as well as it causing PML in SIV or SHIV-infected macaques similar to disease in human AIDS patients infected with JC virus. SV40 is potentially zoonotic, identified as a contaminant in early polio vaccines and is seroprevalent in people working with macaques.(3,4) There is public concern over SV40 vaccine contamination, and there has been extensive research into oncogenicity of SV40 in people as it is known to cause a host of neoplasms in hamsters.(7)

SV40 is of particular utility in research due to its comparative ease to grow in culture as well as it causing PML in SIV or SHIV-infected macaques similar to disease in human AIDS patients infected with JC virus. SV40 is potentially zoonotic, identified as a contaminant in early polio vaccines and is seroprevalent in people working with macaques.(3,4) There is public concern over SV40 vaccine contamination, and there has been extensive research into oncogenicity of SV40 in people as it is known to cause a host of neoplasms in hamsters.(7)

Neuropathology of SV40 can be PML or meningoencephalitis, though some overlap does occur.(2) PML is hypothesized to occur in animals with underlying SV40 infection that subsequently are immunosuppressed, while macaques with more inflammatory than demyelinating lesions were SV40-negative at the time of SIV infection with subsequent experimental SV40 infection.(8,2) PML occurs due to infection and subsequent loss or dysfunction of myelin-producing oligodendroglia. In addition to the demyelination, a unique histopathologic feature of PML in macaques are the gemistocytic astrocytes with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and bizarre nuclei.(6) The gitter cell infiltration and gliosis are a secondary reaction to the breakdown of myelin. The more inflammatory manifest-tation of neurologic SV40 is characterized by leptomeningeal edema and perivascular and multifocal plaque-like infiltrates of lymphocytes and macrophages with extension of inflammatory cells into cortical gray matter.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The pathogenesis of infection and corresponding CNS lesions in this case was also discussed. Recrudescence of the virus secondary to immunosuppression results in infection of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, with loss of oligodendrocytes resulting in the demyelinating lesion seen histologically.

Multifocal to coalescing areas of necrosis and loss of the white matter constitute approximately 10% of the section, and are located primarily at the junction of the grey and white matter which contain numerous gemistocytic astrocytes and gitter cells. Additional characteristics include mild spongiosis and multifocal dilation of axon sheaths. There was a discussion regarding the chronicity of these lesions with some participants interpreting areas of pallor as having abundant astrocytic fibers, less debris and fewer gitter cells, indicating a developing astrocytic scar. Immuno-histochemistry for glial fibrillary acidic protein proved that many of the filaments traversing these areas are indeed astrocytic processes.

References:

1. An P, S+â-íenz Robles MT, Pipas JM. Large T antigens of polyomaviruses: amazing molecular machines. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012. 66:213-236.

2. Axthelm MK, Koralnik IJ, Dang X, et al. Meningoencephalitis and demyelination are pathologic manifestations of primary polyomavirus infection in immunosuppressed rhesus monkeys. J Neuropath Exp Neurol. 2004. 63 (7): 750-758.

3. Engels EA. Cancer risk associated with receipt of vaccines contaminated with simian virus 40: epidemiologic research. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2005 Apr; 4(2):197-206.

4. Engels EA, Switzer WM, Heneine W, Viscidi RP. Serologic evidence for exposure to simian virus 40 in North American zoo workers. J Infect Dis. 2004 Dec 15; 190(12):2065-9.

5. Fahey MA, Westmoreland SV. Nervous system disorders of nonhuman primates and research models. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T. eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. 2nd ed. Vol 2. Waltham, MA: Elsevier; 2012: 739-741.

6. Horvath CJ, Simon MA, Bergsagel DJ et al. Simian Virus 40-induced disease in rhesus monkeys with simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Path.1192 140(6): 1431-1440.

7. Qi F, Carbone M, Yang H, Gaudino G. Simian virus 40 transformation, malignant mesothelioma and brain tumors. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011; 5(5):683-97. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.51.

8. Simon MA, Ilyinskii PO, Baskin GB, Knight HY, Pauley DR, Lackner AA. Association of simian virus 40 with central nervous system lesion distinct from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in macaques with AIDS. Am J Pathol. 1992; 154: 437-446.

9. Verschoor EJ, Niphuis H, Fagrouch Z, et al. Seroprevalence of SV40-like polyomavirus infections in captive and free-ranging macaque species. J Med Primatol. 2008 Aug;37(4):196-201. doi:

10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00276.x. Epub 2008 Jan 9.