Signalment:

Gross Description:

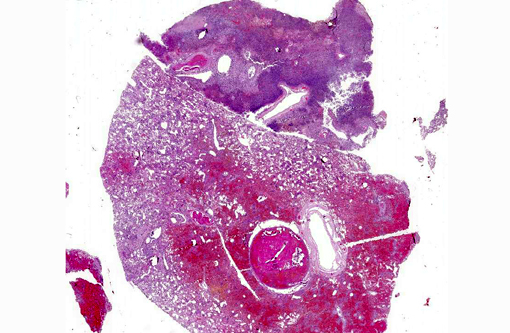

Severe, diffuse pleural thickening and fibrinous pleuritis affected all lung lobes. Severe diffuse pulmonary edema and fibrino-necrotizing pneumonia were present. Multifocal areas of necrotizing and gangrenous pneumonia with colliquative necrosis were evidenced on cut section of lung lobes.Â

Mild pericardial effusion and severe right ventricular and atrial dilation were observed.Â

Histopathologic Description:

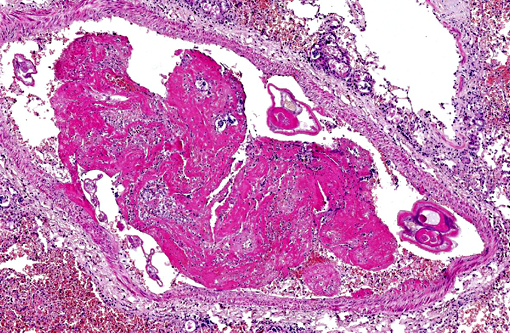

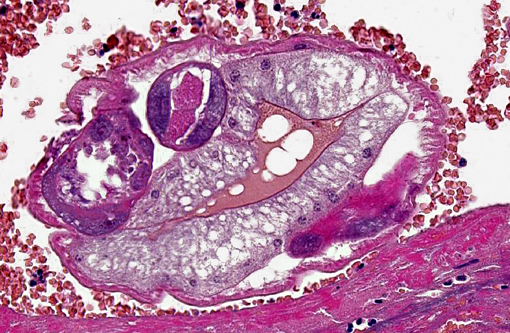

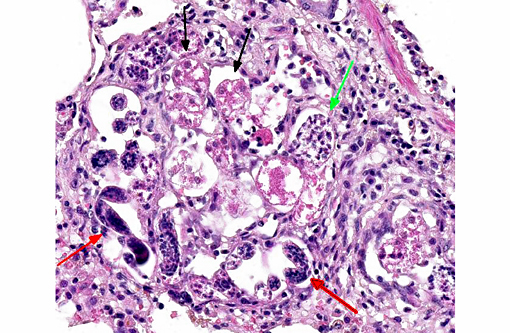

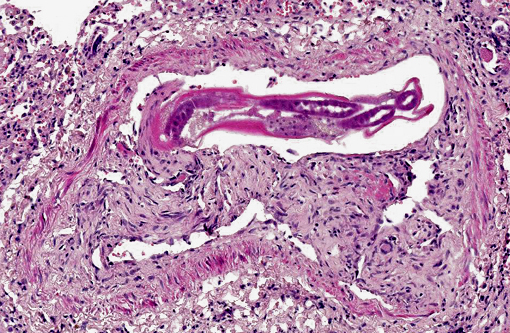

Occasionally, in arterial lumens or embedded in the endoluminal fibrin thrombi there are variable numbers of transverse and longitudinal sections of both viable and degenerated/necrotic adult nematodes associated in some instances with larvae, occasionally with deep basophilic granular material (dystrophic mineralization). Intravascular adult nematodes are approximately 450-550μm in length and 200-250μm in diameter, with a smooth eosinophilic 4-5μm thick cuticle, coelomyarian musculature and a pseudocoelom, in which are detectable tracts of the gastrointestinal tract with an intestine lined by multinucleated cells and of the reproductive male and female tracts, the latter with intrauterine embryonated eggs.

Pulmonary arteries multifocally are occluded by laminated meshwork of pale eosinophilic finely beaded to fibrillar material adherent to the endothelium (fibrin thrombi), occasionally characterized by ingrowth of endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts and slit-like clefts (capillary channels; thrombus organization and recanalization) and extravasated erythrocytes (hemorrhages). Some arterial lumens contain necrotic debris and moderate numbers of both viable and degenerated (karyorrhectic) neutrophils (thrombus dissolution). Multifocally, arteries have medial hypertrophy/hyperplasia with intima bulging within the vascular lumen (luminal narrowing) and endothelium lined by plump reactive endothelial cells (proliferative endoarteritis). The walls of pulmonary arteries are multifocally expanded by extravasated erythrocytes (intramural hemorrhages) or by bright eosinophilic amorphous material (fibrinoid necrosis), in which are embedded degenerated neutrophils (leukocytoclastic vasculitis) with disruption of the wall.Â

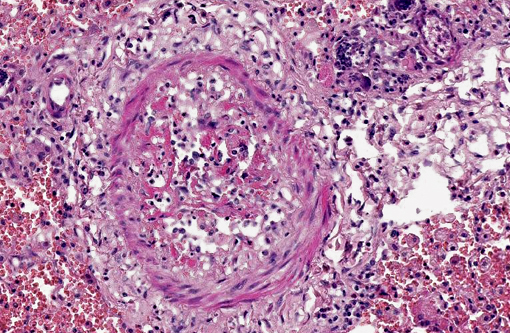

Multifocally expanding alveolar septa, peribronchial interstitium and filling alveolar lumens there are nematode eggs and larvae, or more rarely on adult nematodes. Eggs are round to oval, 40-50μm in diameter, filled with eosinophilic granular material and containing a single basophilic often eccentric, 10μm in diameter nucleus (nonembryonated eggs) or are oval, 150x50μm and are multinucleated (embryonated eggs). Larvae are 150x50μm and are composed of numerous, round, 4-6μm in diameter, basophilic nuclei with scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and a smooth 1μm wide amphophilic cuticle.Â

Larvae and eggs are occasionally free in the alveoli but more frequently are surrounded by inflammatory cells composed by a prevalence of epithelioid macrophages, foamy reactive macrophages, occasionally containing golden granular material (hemosiderin), and by lesser numbers of multinucleated giant cells with up to 7 haphazardly arranged nuclei (foreign body-type) and rare eosinophils and granulocytes. Granulomas are multifocally surrounded by dense fibrous tissue.Â

Multifocally the lung is characterized by locally extrensive areas of coagulative necrosis (pulmonary infarcts) associated often with hemorrhages and/or hematoidin (chronic hemorrhages). Alveoli not affected by the inflammatory process are characterized by edema, rupture of alveolar septa and blunted clubbed ends (alveolar compensatory emphysema) or atelectasis. Diffusely, alveolar capillaries are engorged by erythrocytes (alveolar septa hyperemia).

In some of the examined slides are also detectable:

-intrabronchial and intrabronchiolar nematode larvae, admixed with sloughed epithelial cells and a moderate amount of eosinophilic cellular and karyorrhectic necrotic debris;

-bronchioles lined by a multifocally ulcerated epithelium, with denuded lamina propria;

-thickening of the pleura, expanded up to 8-10 times normal by collagen bundles (fibrosis);

-alveolar septa lined by plump type II pneumocytes (type II pneumocytes hyperplasia)

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Pulmonary multifocal to locally extensive necrosis (pulmonary infarcts) and hemorrhage with multifocal occlusive arterial thrombosis with variable numbers of adult nematodes, larvae and eggs and multifocal moderate subacute proliferative endoarteritis.Â

2. Multifocal to coalescing severe chronic granulomatous and eosinophilic pneumonia, with intralesional nematode adult, larvae and eggs, with multifocal severe subacute pulmonary coagulative necrosis (infarcts), hemorrhages and hemosiderosis

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In the first part of 2014 (February, March, April), an increased number of dogs (at least one every week) have been referred for necropsy at our institution and have been diagnosed with massive pulmonary nematodiasis with parasitological identification of A. vasorum. Italy is considered one of the European countries where this nematode is spreading rapidly.(7) In Northern Italy, this year has been for the most part a warm winter with mild temperatures that have caused an increased survival/vitality rate of intermediate hosts and larvae of A. vasorum

An increased emergence of canine heartworms and lungworms has been reported in Europe. This increase may have many drives including global warming, changes in vector epidemiology and movement of animal populations.(19) Survival rates of A. vasorum L1 larvae have been demonstrated to be influenced by temperatures and temperatures over 10° celsius influencing positively larval development into infective L3 stage larvae.(8,9) Also, larval burdens within slugs are highly dependent on temperatures.(9)

Additional risk factors in dogs include age (higher risk in younger dogs), season (more cases earlier in the calendar year), and worming history (lower risk if given milbemycin oxime in the past 12 weeks).(13) No history was available in this dog; however, young age and early in the year (February) were compatible with these observations.Â

Angiostrongylus vasorum, French heartworm, is a metastrongyloid parasite found in the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle of wild and domestic canids and various other animal species.(5,19) The natural definitive hosts are foxes. The geographic distribution of the parasite includes various countries of Europe, Africa, South America, and North America. In North America, autochthonous A. vasorum infection occurs only in the Canadian province of Newfoundland-Labrador.(5) Angiostrongylosis is considered an emerging disease in dogs in Europe(19) and North America.(5) At present, angiostrongylosis is considered endemic in parts of France, southwestern England, Ireland, Denmark, Italy, Spain, Germany, Hungary, Finland, Switzerland, and Turkey, in South America in Brazil and Colombia, and in Uganda.(2)

However, in the last decade, a relatively new endemic focus of A. vasorum infection has emerged in eastern Canada, in the provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador.(2) The reasons of increased emergence are little known but many drivers such as global warming, changes in vector epidemiology and movements in animal populations may be taken into account.

A. vasorum is a nematode of the superfamily Metastrongyloidea, family angiostrongylidae. The life cycle of A. vasorum is indirect. Adults inhabit the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle of dogs and foxes.(3, 7) Red foxes and other species of wild foxes serve as natural definitive hosts and are an important reservoir of infection for dogs.(7) Natural infection has also rarely been reported in other species including badgers, wolves and coyotes. (3, 7) Gastropods such as snails and slugs but, also amphibians such as frogs may serve as intermediate hosts. Gastropods become infected with L1 when foraging on infected feces or on contaminated plant material. In the intermediate host, the larvae mature and develop into second-stage and third-stage larvae (L2 and L3). The final host, usually a fox or dog, becomes infected by eating an intermediate host containing L3. The slug or snail is digested within the stomach or intestine of the canid, releasing L3 that penetrate the gastrointestinal tract wall, migrate to visceral lymph nodes, and eventually develop into immature adults. The juvenile worms migrate via portal circulation to the liver, caudal vena cava, the right atrium, right ventricle, and pulmonary arteries where they reach maturity approximately 33 to 35 days post-infection. The prepatent period for A. vasorum is approximately 38 to 57 days.(2, 5)

Clinical signs associated with angiostrongylosis may be diverse and a range of signs is described in the above reports. However, two prevalent clinical syndromes predominate; respiratory disease caused by the inflammatory response to eggs and migrating larvae, and hemorrhagic diatheses manifesting as local or diffuse hemorrhages.(4,15) Clinical features include cardiorespiratory (63%), coagulopathic (71%) and other (63%) signs. Cough, dyspnea and tachypnea have been reported as the most common cardiorespiratory abnormalities. Of animals with evidence of coagulopathy, excessive hemorrhage from wounds, airway hemorrhages, epistaxis, hematomas, haemarthrosis, and hematuria have been reported. (4,15) Vague signs of exercise intolerance, lethargy and weakness may be present.(15)

Most cases develop chronic heart failure, but acute interstitial pneumonia occurs in heavily infected dogs. Pulmonary arterial hypertension seems to develop rarely despite the severe lung lesions in chronic cases.(14) Other uncommon manifestations include disseminated intravascular coagulation, uveitis in response to aberrant migration to the anterior chamber of the eye,(3) hemothorax(16) and hemoabdomen.(22)

Acute neurological signs caused by hemorrhages in the central nervous system (brain and/or spinal cord) have been reported.(6,10,11, 21) In these cases, results of coagulation assays are inconsistent for certain authors(11) while others find consistently coagulopathy and associated pulmonary hemorrhages.(6,10)

Neurological signs reflect the site of lesions and may include seizures, various cranial nerve deficits, vestibular signs, proprioceptive deficits, ataxia and paraplegia.(6,10,11, 21) Thoracic radiographs (n = 19) identified abnormalities in 100% of cases.(15) A variety of changes were observed, the most typical being a patchy alveolar-interstitial pattern affecting the dorso-caudal lung fields.(4)

Dogs may exhibit increased total white blood cell counts with transient neutrophilia and eosinophilia. Also increase in serum globulins and a decrease in serum fructosamine have been found.(23) Variably severe anemia (hematocrit ⤠0.20 L/L) and thrombocytopenia characterize dogs with hemorrhagic diatheses. Prolonged prothrombin time and/or activated partial thromboplastin and BMB values have been observed.(4)

The mechanism behind the coagulation defects is poorly understood but most authors have suggested that antigenic factors secreted by the parasites cause excessive intravascular coagulation and a consumptive coagulopathy.(4) Dogs with neurological signs may demonstrate high concentrations of protein and evidence of erythrophagia in the cerebrospinal fluid.(23)

Lesions during the prepatent period are mild. Adult, 14-21 mm long worms are present in the pulmonary arteries, and the lungs contain a few 1-2 mm red nodules, consisting of aggregates of eosinophils and mononuclear cells.(3) More severe lesions develop at the time of patency, including proliferative endoarteritis in response to the adult worms in the pulmonary arteries, and granulomatous to pyogranulomatous pneumonia as a consequence of embolized eggs and larvae.(2,3) Arterial lesions include thrombosis, thickening of the tunica intima by fibromuscular tissue, medial hypertrophy, and lymphoplasmacytic aggregates in the adventitia.(2,3,6,17) Pulmonary lesions consist of red or golden-brown, nodular or confluent areas of hemorrhage, edema, and firmness at the periphery of the lung.(2,3) Histologically, coalescing granulomas formed by macrophages and giant cells are centered on parasite eggs and larvae in the lung are present with variable association with necrosis, neutrophils and eosinophils.(2,3,6,17) There is mild proliferation of type II pneumocytes, alveolar hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and arteriolar thrombosis.(2,3,17) Fibrosis and recanalization of arterial thrombi develop as the lesion ages. Similar granulomas developing around dead or degenerating worms have been reported in brain, kidney, and various tissues.(3) Foci of granulomatous interstitial pneumonia can often be found in which worm remnants may no longer be identified. Central nervous system hemorrhages have also be observed.(2) Definitive ante-mortem diagnosis is by detection of L(1) in feces, sputum, or bronchoalveolar lavage samples. Baermann fecal examination is the most reliable method for fecal detection.(5) However, false negative results can occur due to the typical erratic/sporadic fecal larval shedding pattern of A. vasorum.(5,6) However, this method has been reported to have low sensitivity. Only recently has an increased repertoire of techniques for A. vasorum infection diagnosis been reported, such as detection of L1 in broncho-alveolar lavage fluid and the development of a sandwich ELISA to detect circulating antibodies and worm excretory/secretory antigens.(18,20)

Diagnosis has been achieved by testing fecal samples and blood of foxes and domestic dogs by PCR.(1,12) Definitive diagnosis requires extraction of intact adults from the lungs, as the histologic appearance is similar to Andersonstrongylus milksi. Angiostrongylus can be differentiated from Dirofilaria by examination of intact adults, or by histologic examination. Angiostrongylus has thin coelomyarian musculature, a large, strongyloid intestine composed of few multinucleate cells, and eggs in the uterus. The females have a "barber-pole" appearance due to the helically arranged red gut and white ovaries. The larvae in the lungs are wider and more developed than the microfilariae of Dirofilaria. In contrast, Dirofilaria has well-developed coelomyarian musculature, a smaller intestine, and a uterus containing microfilariae.(3)

Current treatment options include moxidectin, milbemycin oxime, and fenbendazole.(5) However, killing the worms with an anthelmintic may incite severe response.(3,10,11)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

1. Al-Sabi M, Deplazes P, Webster P, Willesen J, Davidson R, Kapel C: PCR detection of Angiostrongylus vasorum in faecal samples of dogs and foxes. Parasitol Res 107: 135-140, 2010

2. Bourque A, Conboy G, Miller L, Whitney H: Pathological findings in dogs naturally infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. J Vet Diagn Invest 20: 11-20, 2008

3. Casewell J, Williams K: Respiratory system, 5th ed., vol. 2, p. 648. Esevier, 2007

4. Chapman PS, Boag AK, Guitian J, Boswood A: Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in 23 dogs (1999-2002) . J Small Anim Pract 45: 435-, 2004

5. Conboy G: Canine angiostrongylosis: the French heartworm: an emerging threat in North America. Vet Parasitol 176: 382-389, 2011

6. Denk D, Matiasek K, Just FT, Hermanns W, Baiker K, Herbach N, Steinberg T, Fischer A: Disseminated angiostrongylosis with fatal cerebral haemorrhages in two dogs in Germany: A clinical case study. Vet Parasitol 160: 100-108, 2009

7. Eleni C, Grifoni G, Di Egidio A, Meoli R, De Liberato C: Pathological findings of Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Central Italy, with the first report of a disseminated infection in this host species. Parasitol Res 113:1247-50, 2014

8. Ferdushy T, Hasan MT: Survival of first stage larvae (L1) of Angiostrongylus vasorum under various conditions of temperature and humidity. Parasitol Res 107:1323-1327, 2010

9. Ferdushy T, Kapel CM, Webster P, Al-Sabi MN, Gr+�-+nvold JR: The effect of temperature and host age on the infectivity and development of Angiostrongylus vasorum in the slug Arion lusitanicus. Parasitol Res 107:147-151, 2010

10. Garosi L, Platt SR, MCConnell JF, Wray JD, Smoth KC: Intracranial haemorrhage associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in three dogs . J Small Anim Pract 46: 93-99, 2005

11. Gredal H, Willesen JL, Jensen HE, Nielsen OL, Kristensen AT, Koch J, Rikke KK, Pors S, Skerritt G, Berendt M: Acute neurological signs as the predominant clinical manifestation in four dogs with Angiostrongylus vasorum infections in Denmark . Acta Vet Scan 53: 43-51, 2011

12. Jefferies R, Morgan E, Shaw S: A SYBR green real-time PCR assay for the detection of the nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum in definitive and intermediate hosts. Vet Parasitol 166: 112-118, 2009

13. Morgan ER, Jefferies R, van Otterdijk L, McEniry RB, Allen F, Bakewell M, Shaw SE: Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs: Presentation and risk factors. Vet Parasitol 173:255-261, 2010

14. Nicolle AP, Chetboul V, Tessier-Vetzel D, Sampedrano C, Aletti E, Pouchelon J-L: Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension due to Angiostrongylosus vasorum in a dog . Can Vet J 4: 792-795, 2006

15. ONeill E, Acke E, Tobin E, McCarthy G: Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in a Jack Russell Terrier . Irish Vet J 63: 434-440, 2010

16. Sasanelli M, Paradies P, Otranto D, Lia RP, De Caprariis D: Haemothorax associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in a dog . J Small Anim Pract 49: 417-420, 2008

17. Schnyder M, Fahrion A, Riond B, Ossent P, Webster P, Kranjc A, Glaus T, Deplazes P: Clinical, laboratory and pathological findings in dogs experimentally infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum . Parasitol

Res 107: 1471-1480, 2010

18. Schucan A, Schnyder M, Tanner I, Barutzki D, 19 D, Deplazes P: Detection of specific antibodies in dogs infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum . Vet Parasitol 185: 216-224, 2012

19. Traversa D, Di Cesare A, 5 G: Canine and feline cardiopulmonary parasitic nematodes in Europe: emerging and underestimated. Parasit Vectors 3: 62-84, 2010

20. Verzberger-Epshtein I, Markham R, Sheppard J, Stryhn H, Whitney H, 5 G: Serologic detection of Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs. Vet Parasitol 151: 53-60, 2008

21. Wessmann A, Lu D, Lamb C, Smyth B, Mantis P, Chandler K, Boag A, Cherubini G, Cappello R: Brain and spinal cord haemorrhages associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in four dogs. Vet Rec158: 858-863, 2006

22. Willesen JL, Bjornvad CR, Koch J: Acute haemoabdomen associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in a dog: a case report . Irish Vet J 61: 591-593, 2008

23. Willesen JL, Jensen AL, Kristensen AT, Koch J: Haematologicaland biochemical changes in dogs naturally infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum before and after treatment . Vet J 180: 106-111, 2009