Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 11, Case 4

Signalment:

Five-month old, male, Japanese black, bovine (Bos taurus)History:

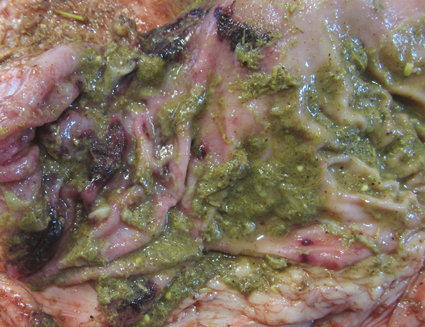

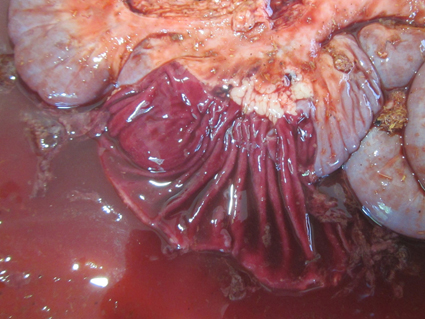

Gross Pathology: At necropsy, a small amount of bloody feces was attached to the anal area. The lung showed multiple consolidation with caseonecrotic foci. The abomasum had multiple erosions and ulcers in the pyloric part of mucosa. From the duodenum to rectum, the mucosa was dark red and covered with dark red, watery or fibrinous contents. The thymus, both the cervical and thoracic parts, was membranous, showing to be atrophic. The gallbladder was almost empty of bile and had streaks of dark red mucosa.Laboratory Results:

No bacteria were isolated from liver, spleen, kidney, heart, lung, or brain. Neither Salmonella nor Clostridium perfringens were isolated from cecal and jejunal contents, respectively. PCR tested positive for Mycoplasma bovis from the lung, negative for BVDV from the kidney, and positive for BAV from the liver, kidney, heart, lung, and cecal content. BAV was isolated from the liver, kidney, heart, lung, and cecal content. The isolate was identified to be BAV type 5 by sequencing the hexon gene.Microscopic Description:

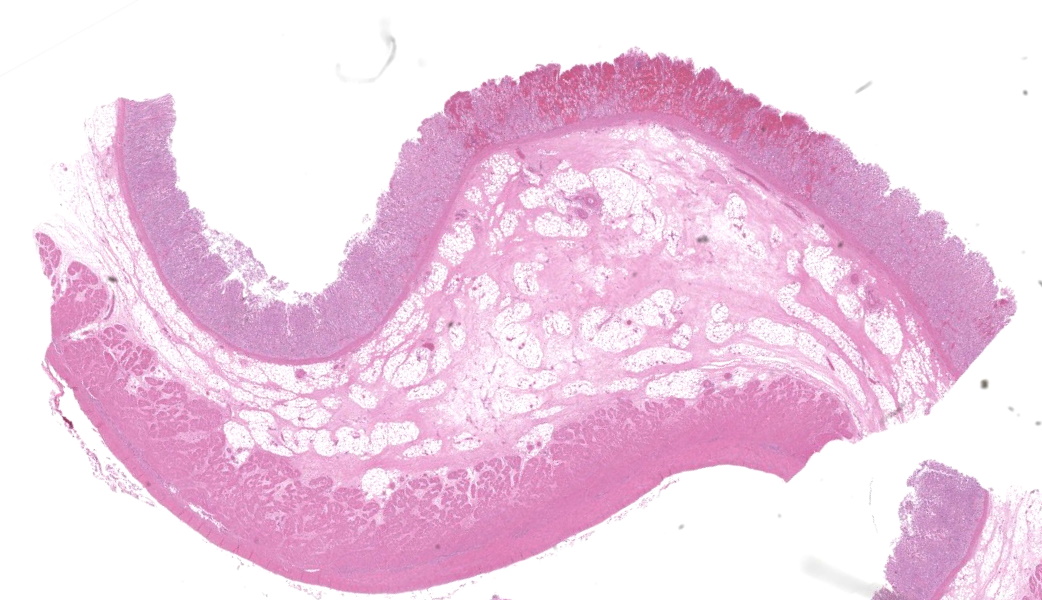

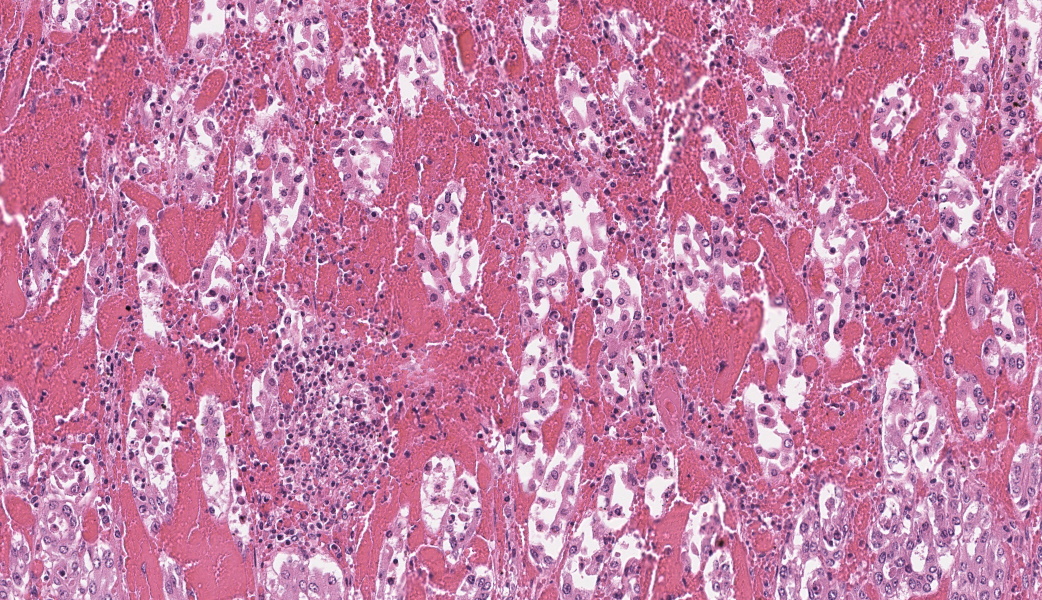

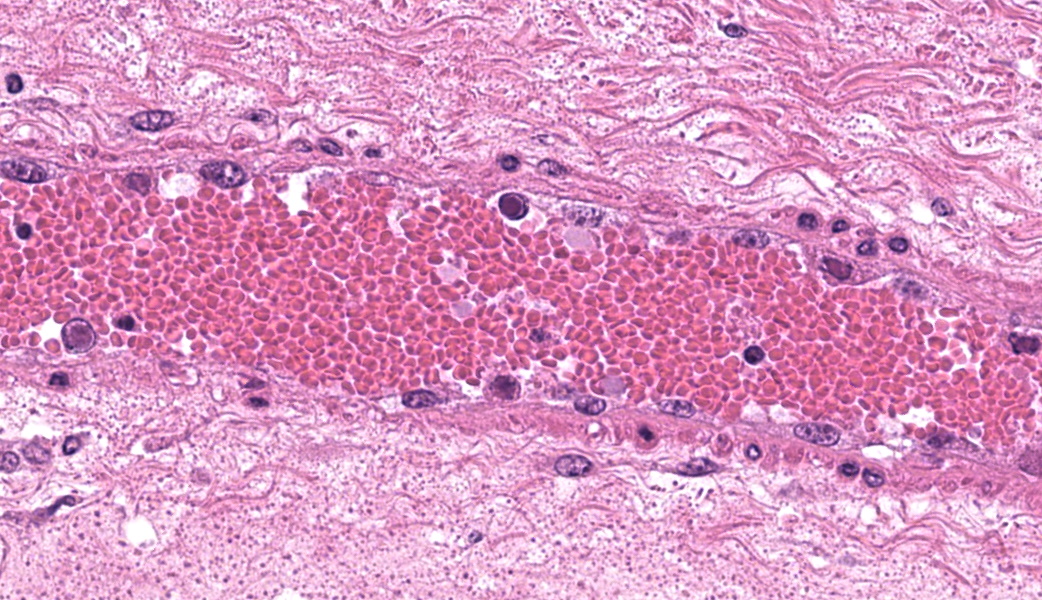

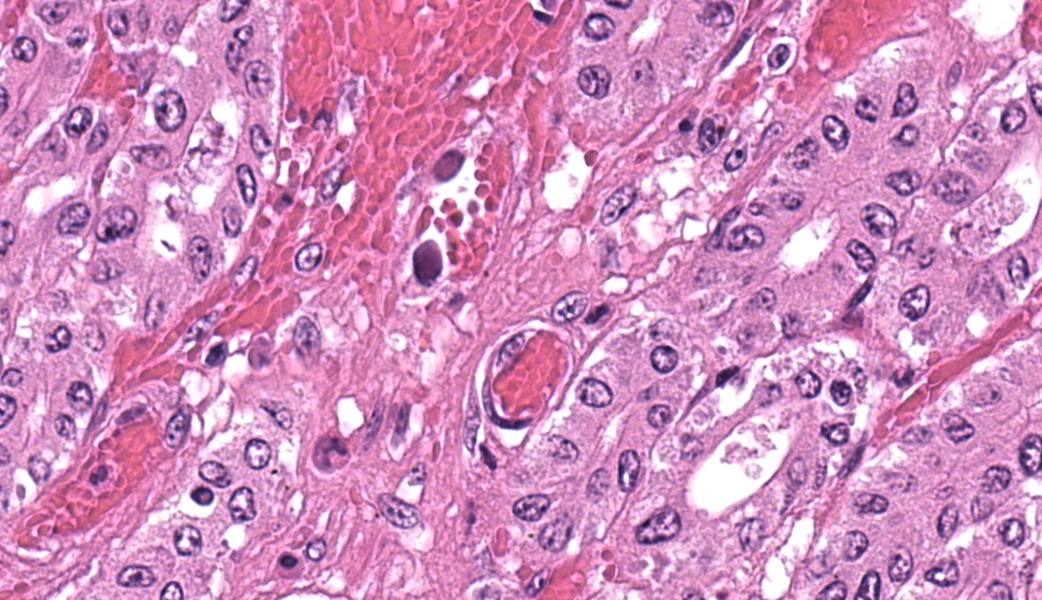

In the abomasum, focally extensive hemorrhage and edematous swelling were present in the lamina propria mucosa and in the submucosa, respectively. In the lamina propria mucosa, the capillary blood vessels and small veins showed severe congestion and hemorrhage. The endothelial cells of these vessels and arterioles had basophilic to amphophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies, of either full type or Cowdry type A. Occasionally, focal areas of necrotic mucosal epithelium were accompanied by neutrophil infiltration. In the submucosa, the endothelial cells of blood vessels had the same intranuclear inclusion bodies. Fibrinous and proteinous or serous materials were accumulated in some parts of the submucosal tissue. Neither bacteria nor fungi were detected by Gram and Giemsa stain, and by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott methods, respectively.Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Abomasum: abomasitis, hemorrhagic, focally extensive, with endothelial intranuclear inclusion bodies.Contributor's Comment:

The present case was characterized pathologically by adenoviral hemorrhagic gastroenteritis and mycoplasmal caseonecrotic bronchopneumonia. The endothelial intranuclear inclusion bodies were detected histologically in the gastrointestinal tract (abomasum, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon, and rectum), liver, gallbladder, spleen, kidney and lung. The forestomach and brain contained no endothelial intranuclear inclusion bodies. In the abomasum, focal ulceration was associated with hemorrhagic abomasitis (No ulceration in the submitted sections). In the ileal Peyer's patch, lymphocytes were severely depleted. Epitheliotropic BAV inclusion bodies were not observed in any organs. By immunohistochemistry, the endothelial intranuclear inclusion bodies showed positive cross-reaction to anti-BAV type 7, weak cross-reaction to anti-BAV type 1, but negative for anti-BAV type 3 antisera. By transmission electron microscopy, the endothelial cells of hepatic sinusoids had paracrystalline arrays of adenovirus-like particles, 60-80 nm in diameter, in their nuclei.BAV belong to the family Adenoviridae, genera Mastadenovirus, and Atadenovirus.8 The serotypes of BAV-1, -2, -3, -9 and -10 belong to the genus Mastadenovirus, and the serotypes of BAV-4, -5, -6, -7, and -8 belong to the genus Atadenovirus.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,10 Serotypes 3, 4, 7, 10 have been associated with enteric disease.4,7,8 BAV, including serotypes 3, 7 and 10 has also been associated with respiratory disease.2,4,5,6 BAV-5 was isolated from a calf with weak calf syndrome, but not have been fully associated with severe gastroenteric disease.1

Adenovirus infections in animals appear, in general, to be subclinical, and disease seems to occur more commonly in immunologically compromised individuals.8 In the present calf, the stress and debilitation caused by transportation and by mycoplasmal pneumonia might have caused immunosuppression, followed by systemic BAV-5 infection and gastroenteritis.

The pathogenesis of adenoviral gastroenteritis in calves is not fully clarified. It appears that after an initial viremic stage, the virus localizes in the endothelial cells of vessels in a variety of organs, resulting in thrombosis with subsequent focal areas of ischemic necrosis.8 Especially, in the bovine gastrointestinal tract, it appears that the endothelial cells of capillary and small veins are highly susceptible to cytopathic effect of the BAV-5 strain. Severely swollen and necrotic endothelial cells may impede the blood circulation through the lamina propria, leading to severe congestion, followed by hemorrhage per diapedesis and per rhexis.

Contributing Institution:

National Institute of Animal Health, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), 3-1-5Kannondai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 3050856, Japan, (WSC ID95)http://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/english/niah/index.html

JPC Diagnoses:

Abomasum: Abomasitis, necrohemorrhagic, acute, focally extensive, severe, with submucosal edema and endothelial intranuclear viral inclusions.JPC Comment:

This was a beautiful example of a classic entity that served as a nice little dessert to wrap the conference up. The endothelial intranuclear viral inclusions (and their ubiquitous distribution) in this case are textbook-worthy (have you ever considered how many histologic images in veterinary pathology texts come from the WSC?)As some participants struggled minimally with tissue identification in this case, a quick review of abomasal microanatomy is in order, as not all regions of the abomasum are identical. Chief and pyloric cells are only found in the fundic portion of the abomasum, whereas the pylorus and cardia lack these. Additionally, there are no goblet cells. The lack of goblet cells in this section immediately rules out large intestine, Other helpful hints include the tortuosity of gastric pits, whereas intestinal crypts are straight. Adipose tissue is not found in the intestinal submucosa but can be seen in the submucosa of the ruminant abomasum and in the equine cecum. Lastly, the degree of autolysis can also be used as a clue. The intestines tend to have a high degree of autolysis due to the milieu of bacterial flora that reside within. The stomach, on the other hand, is a borderline sterile environment that very few bacteria can tolerate due to the level of acidity (unless you are Helicobacter spp…), so there is generally little autolysis.

The contributor’s write-up of bovine adenoviruses covered much of what was discussed in conference about this ubiquitous and relevant viral family. While the pathogenesis is not well-understood, the abomasum in this case had a significant, wedge-shaped hemorrhagic infarct on the H&E slide that tied in well to the current hypothesis on the pathogenesis of this virus. It is thought that viral targeting of endothelial cells and subsequent endothelial viral inclusions may disrupt blood flow to some degree, leading to turbulence and increased incidence of thrombosis of smaller vessels that can lead to ischemic infarcts.9 There was conversation on whether this should be morphed as an abomasitis or a vasculitis due to the endothelial targeting. It was ultimately the opinion of participants that this would not classify as true vasculitis due to the lack of inflammation in vessel walls.

Conference concluded with a quick review of the viruses that form paracrystalline arrays on electron microscopy, which include adenovirus, polyomavirus, papillomavirus, picornavirus, circovirus, iridovirus, birnavirus, and flavivirus and a brief overview of a few pertinent adenoviruses in other species that would likely qualify as important boards-fodder. The main one on that list was canine adenovirus-1, which causes infectious canine hepatitis usually in puppies less than 10 days old and can also cause “blue eye” secondary to the corneal edema sometimes seen with this virus. The other notable mentions were avian adenovirus serovars 4 and 8, which cause inclusion body hepatitis and hydropericardium syndrome in poultry, and type II avian adenovirus, which causes hemorrhagic enteritis and marble spleen disease in turkeys.

References:

- Coria MF, McClurkin AW, Cutlip RC, et al. Isolation and characterization of bovine adenovirus type 5 associated with “weak calf syndrome”. Arch Virol. 1975;47:309-317.

- Fent GM, Fulton RW, Saliki JT, et al. Bovine adenovirus serotype 7 infections in postweaning calves. Am J Vet Res. 2002;63(7):976-978.

- Graham DA, Calvert V, Benk? M, et al: Isolation of bovine adenovirus serotype 6 from a calf in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 2005;156:82-86.

- Lehmkuhl HD, Cutlip RC, DeBey BM. Isolation of a bovine adenovirus serotype 10 from a calf in the United States. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1999;11:485–490.

- Narita M, Yamada M, Tsuboi T, et al. Immunohistopathology of calf pneumonia induced by endobronchial inoculation with bovine adenovirus 3. Vet Pathol. 2002;39:565–571.

- Narita M, Yamada M, Tsuboi T, et al. Bovine adenovirus type 3 pneumonia in dexamethasone-treated calves. Vet Pathol. 2003;40:128–135.

- Smyth JA, Benko M, Moffett DA, et al. Bovine adenovirus type 10 identified in fatal cases of adenovirus-associated enteric disease in cattle by in situ hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(5):1270–1274.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:143-144.

- Werid GM, Ibrahim YM, Girmay G, Hemmatzadeh F, Miller D, Kirkwood R, Petrovski K. Bovine adenovirus prevalence and its role in bovine respiratory disease complex: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet J. 2025;310:106303.

- Zhu Y-M, Yu Z, Cai H, et al. Isolation, identification, and complete genome sequence of a bovine adenovirus type 3 from cattle in China. Virol J. 2011;8:557-564.