Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 3, Case 2

Signalment:

2-month-old, female, Yorkshire swine (Sus scrofa domesticus).History:

This animal was found dead after exhibiting coughing and poor appetite for an unknown duration. It came from a group of 30 pigs, many of which had pruritus and black “greasy” exudate of the extremities. These animals had been purchased from multiple sources and introduced to the property within the last six weeks. This pig, and several others had areas of pruritic skin with black, “greasy” exudate, most severely on the distal extremities. Previous bacterial culture of these lesions had identified Staphylococcus hyicus.Gross Pathology:

Distal extremities: The dorsal aspects of the pasterns of all four limbs are carpeted with dark brown, crusty, raised plaques. The lesions are most severe on the forelimbs.Thorax: Multifocal strands of tan to yellow friable material (fibrin) are loosely adhered between the pleural surfaces of the lungs and the body wall. The lungs are diffusely wet, heavy, soft, pink and exude dark red fluid on cut section. All examined sections float in formalin. The pericardium contains ~5 mL of pink, clear, watery fluid. The hilar lymph nodes are mildly enlarged to 1.5 - 2x normal size.

Abdomen: The abdomen contains approximately 50 mL of dark red, clear, watery peritoneal fluid. There are multifocal strands fibrin adhered between visceral organs. The stomach contains bright yellow to green semi-liquid ingesta. The descending colon contains formed feces. There is mild congestion in the liver, and black, round, flat spots on the left lateral lobe of the liver.

The remainder of the gross examination is unremarkable.

Laboratory Results:

Bacteriology: Staphylococcus hyicus was cultured from the liver.Microscopic Description:

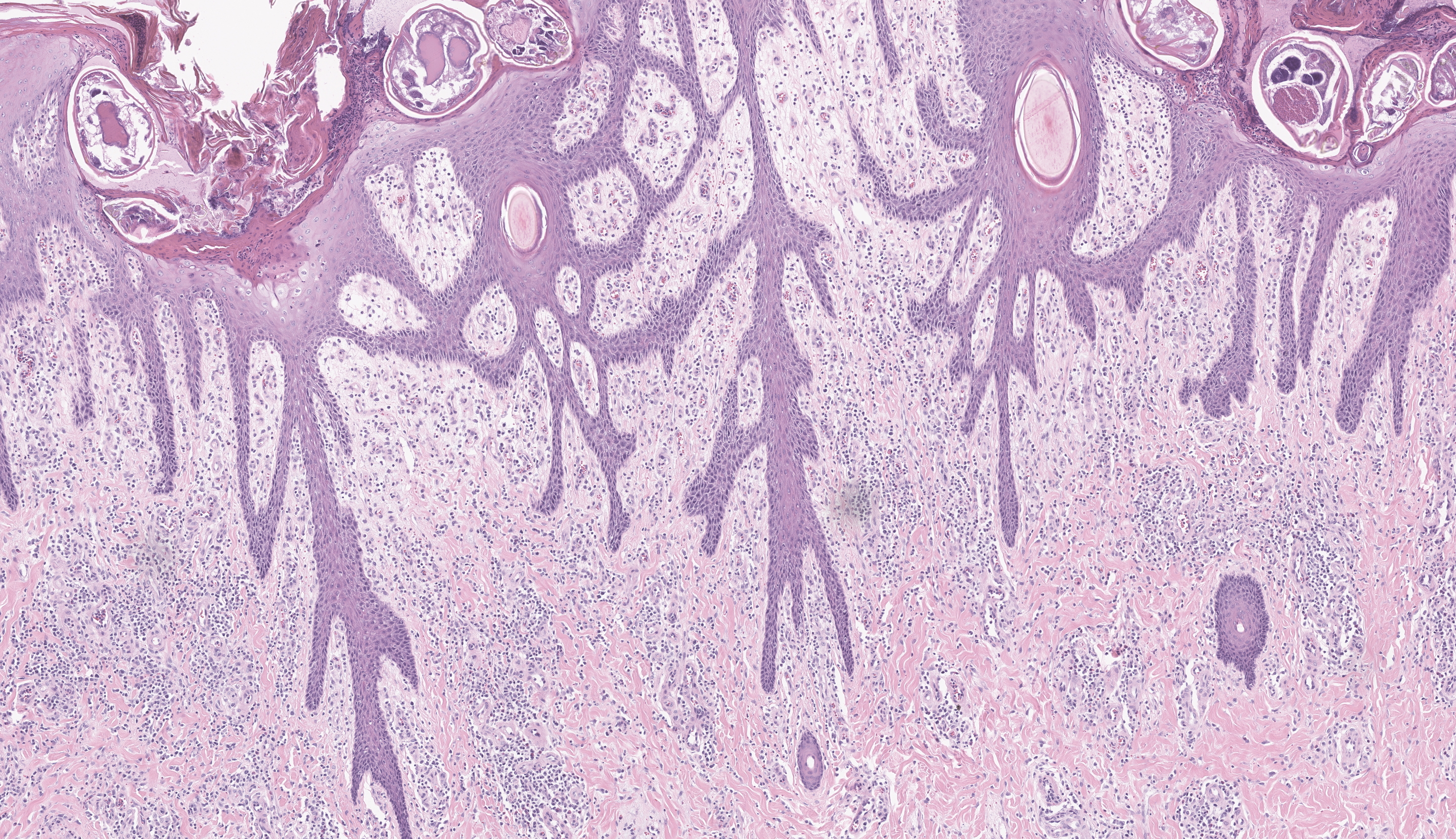

Skin: In the dermis, there is marked parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, with numerous colonies of extracellular cocci, and intracorneal arthropod mites. The mites are up to 300-400 μm in diameter, have a chitinous exoskeleton with dorsal spines, short jointed appendages, striated skeletal muscles, and internal gastrointestinal and reproductive tracts. The mites often contain birefringent internal crystalline material, suspected to be scybala. The epidermis is hyperplastic with prominent rete pegs, and the superficial dermis is infiltrated by marked numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and fewer eosinophils.Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Haired skin: Severe, locally extensive, chronic, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic hyperplastic dermatitis with hyperkeratosis, intralesional arthropods (Sarcoptes scabiei presumed), and numerous colonies of extracellular cocci.Contributor's Comment:

Microscopic evaluation revealed two concurrent pathogenic processes within the exudative skin lesions observed grossly: exudative epidermitis (greasy pig disease) caused by Staphylococcus hyicus, and sarcoptic mange, caused by Sarcoptes scabiei.Staphylococcus hyicus is a Gram-positive, coagulase-variable, facultatively anaerobic bacterium which typically causes disease in piglets between 5 and 60 days old. The most common clinical finding is greasy, often crusting exudate widely dispersed over the body, but most severely affecting the feet. It is typically transmitted from animal to animal, or is sometimes acquired from the environment, and enters the skin through penetrating wounds.3 Strains of Staph hyicus that have the potential to cause clinical disease do so by producing exfoliative toxins. These toxins, including ExhA, ExhB, ExhC, ExhD, SHETA, and SHETB, are thought to cause exfoliation of the epidermis through the cleavage of porcine desmoglein 1, an integral component of the epidermal desmosomes.9 Infections are often introduced into herds by new animals, and morbidity and mortality rates can be high in younger piglets.3 In addition to abrasions and wounds from rough surfaces and fighting, additional predisposing factors for infection are infestation with ectoparasites such as mites.4,7,8 The isolation of Staphylococcus hyicus from the liver in this case suggests the animal developed bacteremia.

Sarcoptes scabiei suis is a specific variety of Sarcoptes scabiei mite which is globally endemic in swine and is the causative agent of Sarcoptic mange. It is typically transmitted by direct contact, but it may also be spread by fomites and can be easily introduced into a naïve herd by a single infected animal or contaminated equipment. This disease is most prevalent in younger animals, and typically manifests as papules which progress to scaling, oozing, crusts, and alopecia, and often progresses to lichenification in chronic cases. Affected areas are afflicted with severe pruritus. The mechanism of injury to the skin is a combination of mechanical trauma caused by the mite’s feeding and burrowing behavior, chemical irritation from ectoparasite saliva and feces, and a hypersensitivity reaction to Sarcoptes antigens.1

Contributing Institution:

University of Missouri Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory https://vmdl.missouri.edu/JPC Diagnoses:

- Haired skin: Epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, diffuse, severe, with mild lymphoplasmacytic dermatitis, intracorneal adult and nymphal mites and eggs.

- Haired skin: Epidermitis, pustular, subacute, regionally extensive, moderate with extracellular cocci.

JPC Comment:

“Greasy pig disease” has been covered several times in the Wednesday Slide Conference, including as recently as last year (Case 1, Conference 4, 2024-2025, Case 1, Conference 9, 2008-2009, and Case 3, Conference 8, 2009-2010). It always provides a solid descriptive opportunity for conference participants and is truly a classic entity. This year’s case, though, had additional guests on the slide in the form of Sarcoptes scabiei suis, making this a great “two-fer” case. The slides provided by the contributor were simply beautiful; you could almost draw a line right down the middle of the tissue to demarcate the more routine lesions from Staphylococcus hyicus on the right side compared to the far more severe lesions on the left from both the mites and the bacteria together. Many thanks to the contributor for an excellent submission of these two infectious dermatologic entities.Conference discussion focused on the virulence factors of S. hyicus that enable it to cause the exudative epidermitis it is famous for. This bacterium has a variety of exfoliative toxins, such as ExhA, ExhB, ExhC, ExhD, Staph hyicus exfoliative toxin A (SHETA), and SHETB. These toxins selectively digest desmoglein-1 in porcine skin.4 Desmoglein-1 is a tight junctional adhesion molecule that is primarily expressed in the superficial epithelium of the skin, playing a critical role in maintaining cell–to-cell adhesion and tissue integrity. When broken down, the cells stop “holding hands” and separate from one another. Coupled with sebaceous hyperplasia within the dermis as a sequela of inflammation, these broken cell junctions enable leakage of sebaceous material onto the surface of the skin, thus the name “greasy pig disease.” Conference participants were also quizzed about other commonly encountered desmogleins, including desmoglein-2 (found in desmosomes in skin, cardiomyocytes, and intestines), desmoglein-3 (found between basilar epithelial cells and their basement membranes in the skin; also the known target of pemphigus vulgaris), and desmoglein-4 (found in desmosomes between epithelial cells both in the epithelium of the skin and in hair follicles, and helps to anchor the hair follicle into the dermis).

Shifting now to the maddeningly itchy Sarcoptes scabiei mite, “Scabies” or “sarcoptic mange” is caused by Sarcoptes scabiei, a burrowing mite, of which there are numerous subspecies that are host specific. Female mites invade the stratum corneum of their selected host and create cozy homes for themselves in the form of tunnels, where they live, move, feed, defecate, and lay eggs.7 Upon locating a host, the mite secretes saliva that lyses the epithelium of the stratum corneum. As the mite works its way deeper with its cutting mouthparts, it uses its two anterior-most pairs of legs to “swim” forward and create a tunnel. The mite intakes water and nutrients from the host’s extracellular fluid and lymph that leaks into the space around the mite’s mouthparts while they dig.7 The females, once mated, will lay their eggs in a burrow that offshoots from their tunnel. The eggs hatch into larvae, which channel their way out of their nursery burrow within the stratum corneum and grow into two subsequent nymphal stages: protonymphs and tritonymphs.7 The tritonymphs mature into adults on the skin and males will roam about looking for unmated females to repeat the life cycle with.

Scabies is most common in tropical countries, but is ubiquitous and can be seen anywhere, including cold regions where people (and animals) will huddle together for warmth, as prolonged physical contact is the main mode of mite transmission between hosts.7 Transmission can occur indirectly on contaminated fomites, but environmental temperature plays a strong role in mite survivability while off-host. Mites don’t survive long in warmer climates, regardless of humidity, due to being unable to maintain water balance, but have increased survivability in cooler temperatures with high humidity.7

So, which came first, the chicken or the egg? It is the opinion of conference participants that, in the case of this particular young pig, the Sarcoptes scabiei suis mites likely set up shop first, causing superficial trauma to the skin of the pig and inducing severe itch, which would have resulted in additional self-trauma from scratching. As a result, the Staphylococcus hyicus, seeing as how they are opportunistic commensals, would have had an easy time infecting the skin further and causing additional dermatologic insult. Talk about an itchy one-two punch.

References:

- Davis DP, Moon RD. Density of itch mite, Sarcoptes scabiei (Acari: Sarcoptidae) and temporal development of cutaneous hypersensitivity in swine mange. Vet Parasitol. 1990;36(3–4):285–293.

- Foo CW, Florell SR, Bowen AR. Polarizable elements in scabies infestation: a clue to diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;40(1):6–10.

- Foster AP. Staphylococcal skin disease in livestock. Vet Dermatol. 2012;23(4):342.

- Fudaba Y, Nishifuji K, Andresen LO, Yamaguchi T, Komatsuzawa H, Amagai M, Sugai M. Staphylococcus hyicus exfoliative toxins selectively digest porcine desmoglein 1. Microb Pathog. 2005;39(5-6):171-6.

- Kim J, Chae C. Concurrent presence of porcine circovirus type 2 and porcine parvovirus in retrospective cases of exudative epidermitis in pigs. Vet J. 2003;167(1):104–106.

- Maes D, Vandersmissen T, De Jong E, Boyen F, Haesebrouck F. Staphylococcus hyicus-infecties bij varkens. Vlaams Diergeneeskd Tijdschr. 2013;82(5).

- Sharaf MS. Scabies: Immunopathogenesis and pathological changes. Parasitol Res. 2024;123(3):149.

- Wattrang E, McNeilly F, Allan GM, Greko C, Fossum C, Wallgren P. Exudative epidermitis and porcine circovirus-2 infection in a Swedish SPF-herd. Vet Microbiol. 2002;86(4):281–293.

- Yun CS, Kang S, Kwon DH, et al. Characterization and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus hyicus from swine exudative epidermitis in South Korea. BMC Vet Res. 2024;20(1).