Signalment:

Gross Description:

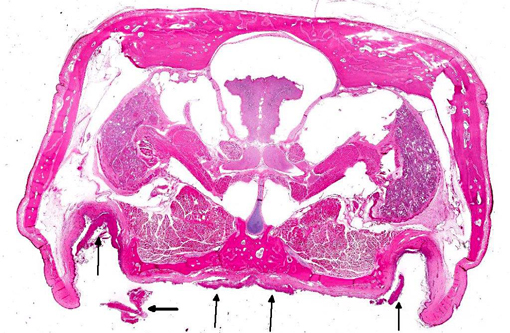

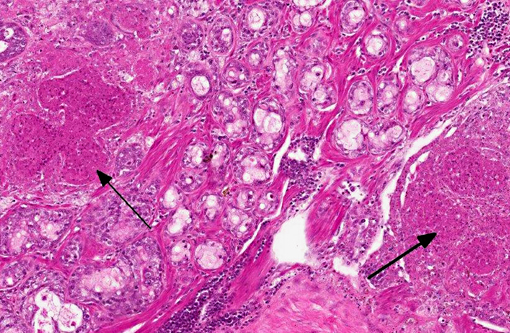

Histopathologic Description:

The lacrimal gland has multifocal mild interstitial lymphocytic inflammation with necrosis.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Oral cavity (hard palate): Stomatitis, heterophilic and lymphohistiocytic, ulcerative, fibrinonecrotic, multifocal to coalescing, subacute, severe, with moderate submucosal lymphohistiocytic perivasculitis, superficial pseudomembrane formation, and superficial bacteria.

2. Lacrimal gland: Adenitis, lymphocytic, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, moderate.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Antemortem oropharyngeal samples were collected from many turtles and submitted for PCR detection. Ranavirus was confirmed in 8 of the 10 tested turtles submitted for necropsy, including all of the turtles with oral plaques similar to the submitted case. In two turtles, PCR was followed by DNA sequencing, identifying the ranavirus frog virus 3 in both cases. Herpesvirus was confirmed in 4 of the 10 tested turtles. Tissue from this turtle was negative for herpesvirus. Several bacterial agents were detected in oropharyngeal and blood samples from other ranavirus-positive turtles in this population, highlighting the potential role of secondary bacterial pathogens as factors contributing to inflammation, sepsis, and death of ranavirus-infected turtles.Â

Ranavirus currently is classified as a genus in the Iridoviridae family. Iridoviruses are large (120-200nm), icosahedral, double stranded DNA viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm. Ranavirus infections are important causes of disease in fish(9) and amphibians.(4) The ranavirus frog virus 3 has been reported with increasing frequency as a significant cause of mortality in several reptile species.(5) Environmental stressors, na+�-�ve or suppressed immunity, or introduction of novel strains may play a role in outbreaks that emerge in wild and captive reptiles. Amphibians and reptiles have been suggested as important reservoirs for ranaviruses that may cause economically and ecologically important disease in finfish.

Typical presentations of ranavirus infection in turtles includes cervical edema, palpebral edema, rhinitis, and stomatitis-glossitis.(5) A series of cases of ranavirus in captive eastern box turtles in North Carolina(1) describes clinical signs that also included cutaneous abscesses, oral erosions and abscesses, and respiratory distress. Other studies that include several species of turtles and tortoises describe similar signs as well as yellow-white oral plaques.(6,7) In these studies, histopathology revealed fibrinoid vasculitis of skin, mucous membranes, lungs, and liver, multifocal hepatic necrosis, multicentric fibrin thrombi, fibrinous and necrotizing splenitis, and necrotizing stomatitis and esophagitis. While basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies have been reported in ranavirus infections,(5) often they are not observed, even with ranavirus infection confirmed by PCR, electron microscopy, or virus isolation.(3,6)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Oral cavity (hard palate): Stomatitis, necrotizing, focally extensive, severe.

2. Lacrimal gland: Dacryoadenitis, necrotizing, multifocal, moderate.

Conference Comment:

The contributor does an outstanding job of covering all the salient features of ranavirus infection in reptiles. Ranavirus, specifically frog virus 3, was initially associated with widespread disease epizootics in amphibians. Affected tadpoles (who are particularly vulnerable to infection) and frogs typically present with cutaneous hemorrhage/ulceration or disseminated disease with multiorgan necrosis. Subclinical infections are common in frogs; the kidneys and macrophage populations are considered the primary sites of virus persistence.(7) Both adult and larval salamanders are susceptible to a ranavirus known as Ambystoma tigrinum virus, which results in splenic, hepatic, renal and gastrointestinal necrosis, sloughing of the skin, and discharge of inflammatory exudate from the vent. Interestingly, ambient temperature appears to play a significant role in disease pathogenesis, as high mortality is observed in those salamanders infected at 18oC, while those infected at 26oC tend to survive.(8) Ranavirus infection in fish populations was first reported in Australian redfin perch and rainbow trout in the 1980s; it has since been implicated in multiple disease episodes in both farmed and wild freshwater fish worldwide. Fingerlings and juveniles are most susceptible, and disease is characterized by severe necrosis in the liver, pancreas and renal/splenic hematopoietic cells. In addition to these tissues, Santee-Cooper virus, a ranavirus in wild largemouth bass, also causes enlargement and inflammation of the swim bladder, resulting in moribund fish that tend to float to the surface. As in amphibians, ranavirus infections in fish can be subclinical.(8) Furthermore, inter-species transmission between amphibians and fish has been demonstrated, implicating both species as potential reservoirs for the virus.(8) Ranavirus is such a significant problem in both fish and amphibians that it meets the criteria for listing by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE).(1)

References:

1. Ariel E. Viruses in reptiles. Vet Res. 2011;42(1):100-112.

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2007:230.

3. De Voe R, Geissler K, Elmore S, Rotstein D, Lewbart G, Guy J. Ranavirus-associated morbidity and mortality in a group of captive eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina carolina). J Zoo Wildl Med: official publication of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians. 2004;35:534-543.

4. Gray MJ, Miller DL, Hoverman JT. Ecology and pathology of amphibian ranaviruses. Dis Aquat Org. 2009;87:243-266.

5. Jacobson ER. Infectious Diseases and Pathology of Reptiles: Color Atlas and Text. Boca Raton, FL: CRC/Taylor & Francis; 2007:288, 404-406, 440.

6. Johnson AJ, Pessier AP, Jacobson ER. Experimental transmission and induction of ranaviral disease in Western Ornate box turtles (Terrapene ornata ornata) and red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans). Vet Pathol. 2007;44:285-297.

7. Johnson AJ, Pessier AP, Wellehan JF, Childress A, Norton TM, Stedman NL, et al. Ranavirus infection of free-ranging and captive box turtles and tortoises in the United States. J Wildl Dis. 2008;44:851-863.

8. MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ, eds. Fenners Veterinary Virology. 4th ed. London, UK: Academic Press; 2011:172-175.

9. Whittington RJ, Becker JA, Dennis MM. Iridovirus infections in finfish - critical review with emphasis on ranaviruses. J Fish Dis. 2010;33:95-122.