Signalment:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

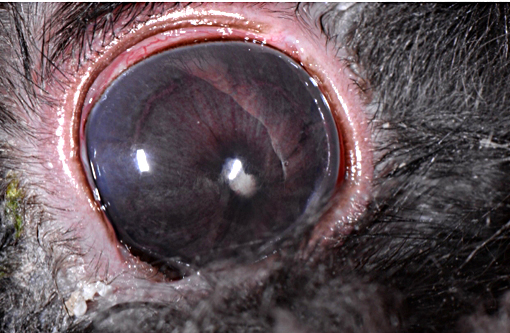

E. cuniculi primarily infects rabbits (Type I genotype), including research colonies used in experimental models of human disease resulting in lesions of E. cuniculi being confused and misinterpreted as lesions associated with more serious human conditions.(10) While seroprevalence for the organism is high in rabbits, infection is often subclinical and associated with incidental renal lesions at necropsy.(6) Seropositive rabbits with clinical manifestations of encephalitozoonosis exhibit signs of vestibular disease (head tilt, ataxia), azotemia with nonspecific anorexia, lethargy and weight loss, and white intraocular masses (granulomas), cataracts and uveitis resulting in enucleation.(5) Microscopic lesions include focal to segmental granulomatous interstitial nephritis (early), fibrosing lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis (chronic) and nonsuppurative granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis.(6) Rabbits with neurological deficits have a more favorable prognosis than those presenting with clinical signs of renal insufficiency.(5)

Dwarf rabbits are especially prone to ocular lesions associated with E. cuniculi including white intraocular masses (granulomas), cataracts and phacoclastic uveitis resulting in enucleation.(6)

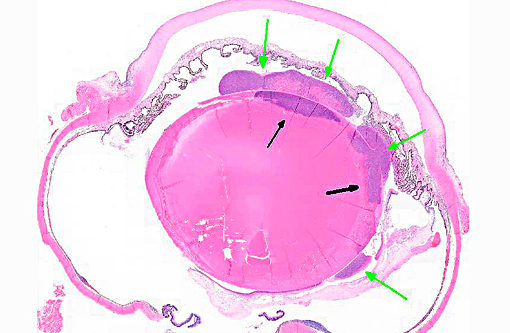

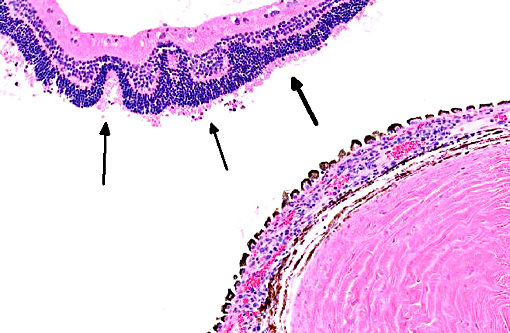

Ocular lesions are mostly unilateral, and rabbits with ocular disease generally do not suffer extra-ocular clinical abnormalities.(5) Intrauterine infection is the proposed route of transmission with ocular encephalitozoonosis. The organism permeates the developing lens resulting in cataract formation, spontaneous rupture of the lens capsule and extrusion of lens substance inciting phacoclastic uveitis characterized by granulomatous inflammation intimately associated with the lens capsule.(5) Posterior synechia, phthisis bulbi and secondary glaucoma are not uncommon sequelae.(2,4,8) Early in the course of ocular disease associated with the organism, phacoemulsification can be used to treat the condition.(2) The tendency of nearly complete lens regeneration from lens epithelial cells requires large capsulectomy to suppress lens regrowth.(1) The prognosis for treatment of phacoclastic uveitis is poor, and enucleation is almost invariable.

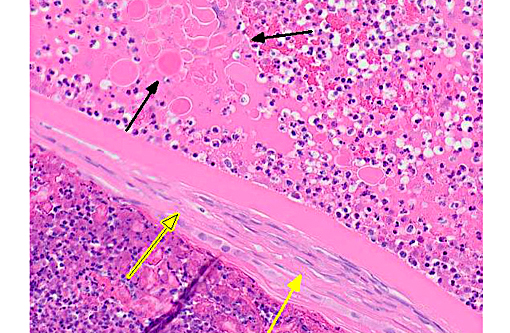

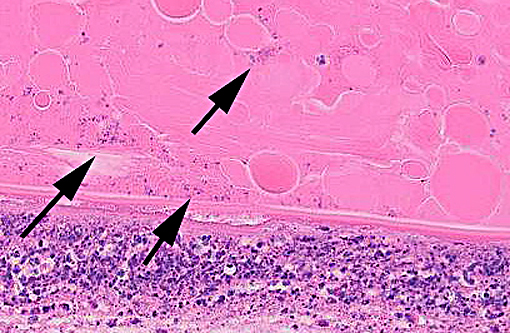

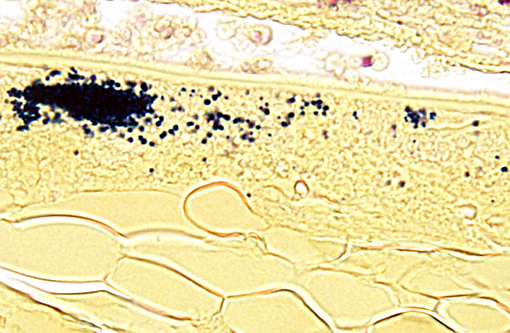

Visualization of small (2-3 micron) spores is challenging with routine H&E stains. Gram, Giemsa, carbon fuschin and Ziehl-Neelsen acid fast stains permit greater visualization of the spores. Immunohistochemical detection of intralenticular E. cuniculi organisms and PCR of liquefied lens substance is especially effective in organism detection.(4,5)

Subclinical chronic infections in lagomorphs (Type I genotype) and dogs (Type III genotype) and the risk for zoonoses in immunocompromised individuals require appropriate precautions and biosecurity when working with infected or at risk populations of these species.(3,9) Disseminated encephalitozoonos in the kidney, sinuses, lung, brain and conjunctiva is well-recognized in AIDS patients.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Although clinical and subclinical E. cuniculi infections were once common in laboratory rabbits, the agent is excluded from most modern facilities. Spores are transmitted primarily by ingestion and inhalation (or transplacentally), and they are shed in the urine of infected animals. E. cuniculi is capable of causing disease in dogs as discussed above, where lesions are most common in the brain and kidney. The organism targets vascular endothelium resulting in segmental vasculitis. Once infected, animals often remain permanently infected as macrophages are incapable of clearing the organism, although organisms can be difficult to find in chronic lesions. Within the kidney, they are most common in the renal tubular epithelium and glomerular capillaries. Gross kidney lesions include nonsuppurative interstitial nephritis.(1) In addition to nephritis and meningoencephalitis, E. cuniculi infections have also been associated with placentitis in horses, squirrel monkeys, blue foxes and an alpaca.(11)

One of the primary differential diagnosis for E. cuniculi is toxoplasmosis. The following characteristics can help differentiate the two organisms: T. gondii is not birefringent, E. cuniculi spores are; T. gondii does not stain with gram, acid fast or Luna stains; T. gondii stains more readily in H&E sections; T. gondii is a larger organism, measuring approximately 3-6um.

Conference participants agreed that this is an excellent descriptive slide, and the conference histologic description was aligned closely with the contributors description above. The inflammation and necrotic debris surrounding the lens was described as containing degenerate eosinophils and heterophils, macrophages and lymphocytes. Within the ruptured lens Morgagnian globules were described as relatively abundant and bladder cells as uncommon. The corneal endothelium is infiltrated with leukocytes, and there is neovascularization and inflammation within the corneal stroma. Microsporidian spores were described as being present extracellularly between lens fibers and rarely within macrophages. Some discussion centered on the nature of the proliferative fibrovascular tissue at the lens margin, i.e. whether the spindled cells represent hyperplastic response or metaplastic lens epithelium. In addition to tissue gram and acid-fast stains, another histochemical stain that can be used to visualize E. cuniculi organisms includes the Luna method.(7)

References:

1. Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015:385.

2. Felchle LM, Sigler RL. Phacoemulsification for the management of Encephalitozoon cuniculi-induced phacoclastic uveitis in a rabbit. Vet Ophthalmol. 2002; 5:211-215.

3. Fournier S, Liguory O, Sarfati C. Disseminated infection due to Encephalitozoon cuniculi in a patient with AIDS: case report and review. HIV Med. 2000; 1:155-161.