WSC 22-23

Conference 23

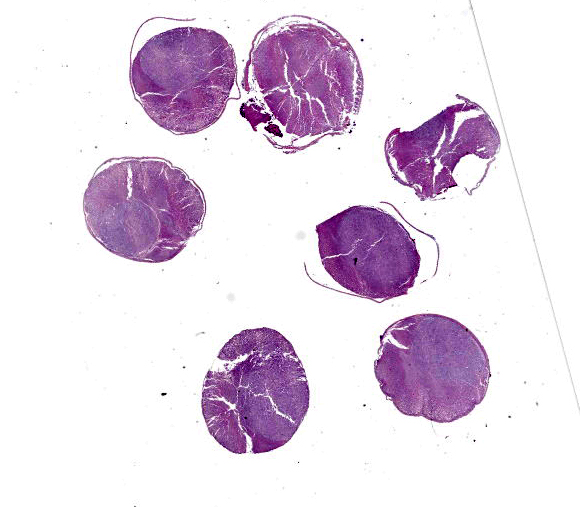

Case 2:

Signalment:

14-year-old neutered male Persian cat (Felis catus)

History:

The cat had an acute onset of difficulty walking on the hind limbs, with a progressive worsening. The cat urinated and defecated in inappropriate places with sagging of the limbs during urination / defecation; had difficulty in jumping and appeared depressed. Palpation of the thoraco-lumbar spine caused discomfort. The cat underwent hospitalization and a complete diagnostic workflow. Due to a severe worsening of the symptoms and the health status, the cat was euthanized, and a necropsy was performed.

Gross Pathology:

An intramedullary neoformation was present in the thoraco-lumbar spinal cord (approximately T7).

Laboratory Results:

Hematobiochemistry: mild leucopenia; hyperazotemia.

Serology for FIV, FeLV, Toxoplasma gondii: negative.

PCR for Feline coronavirus, Neospora caninum, Feline parvovirus, Toxoplasma gondii (liquor): negative.

Liquor cytology: mixed pleocytosis, mainly monocytoid and neutrophilic.

Liver and spleen cytology: mild hepatocellular degeneration; splenic extramedullary hemopoiesis.

Microscopic Description:

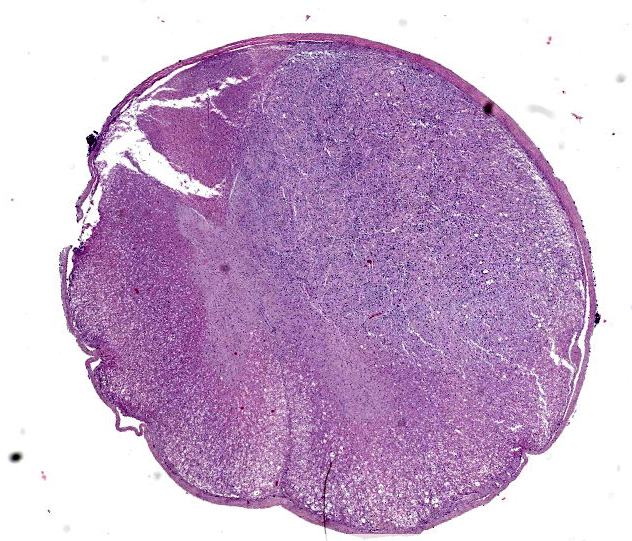

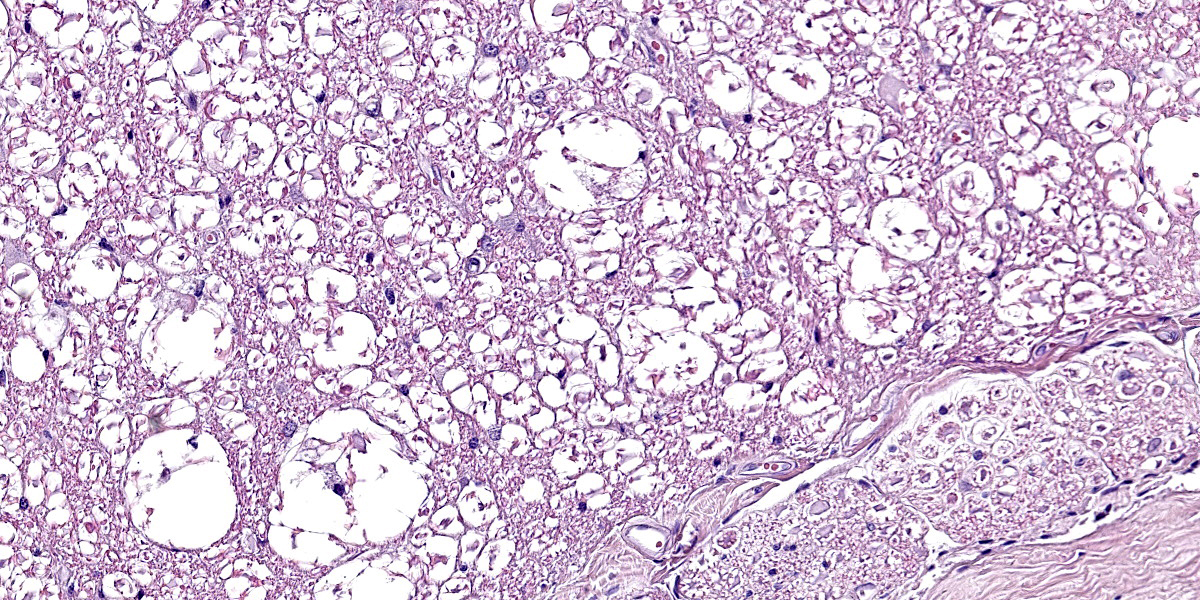

Spinal cord. Focally effacing and replacing about 60% of the grey and white matter compressing the adjacent tissue, there is a nodular neoplasm of 4 mm that is moderately cellular, multifocally infiltrative, moderately demarcated and unencapsulated.

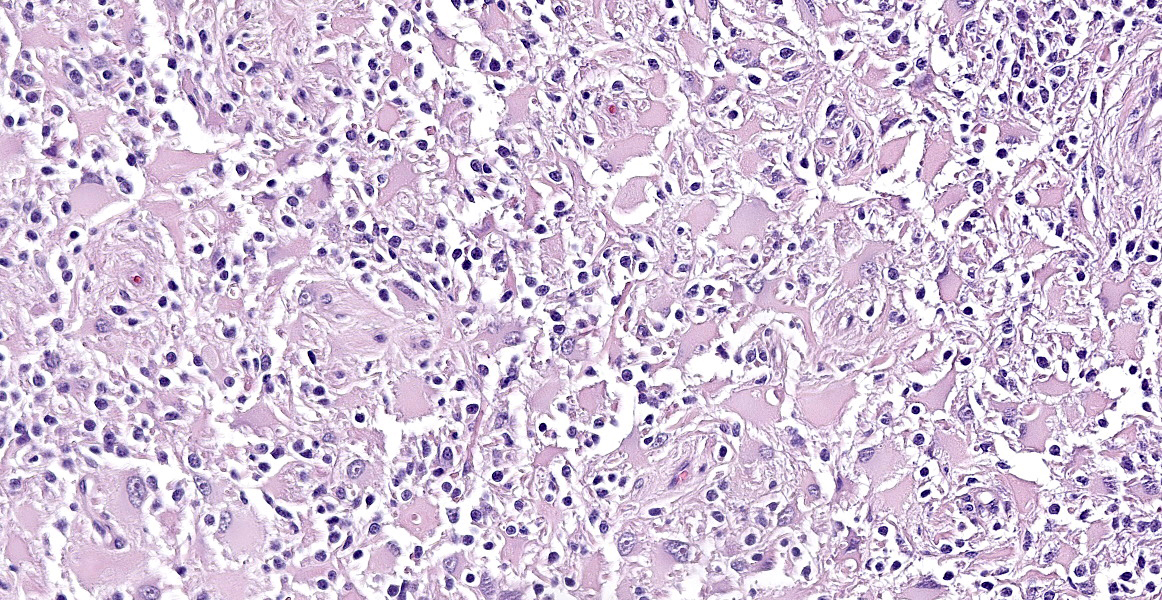

Neoplastic cells are variably arranged in interlacing streams, short bundles, and sheets with scant amounts of supporting fibrovascular stroma. A mixed cell population is present. The predominant neoplastic cells are round to angular, 20-50 microns large, with low nucleus/cytoplasm ratio, variably distinct cell borders and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm that multifocally forms stout processes. Nuclei are 5-15 microns large, round to elongated to pleomorphic, eccentric, with open-faced chromatin and mostly single prominent nucleolus. Rare binucleated neoplastic cells and multifocal megakaryosis are observed. Anisokariosis and anisocytosis are severe (gemistocyte-like cells; 60%). The predominant population is admixed with spindle to stellate cells, 10-15 microns large, with high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio, indistinct cell borders and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are oval to elongated, 6-8 micros large, central with finely stippled chromatin and rarely evident nucleoli. Anisokariosis and anisocytosis are mild (astrocytes; 40%). Mitoses are less than 1 in 2.37mm2.

In the surrounding white matter axonal sheaths are moderately vacuolized (spongiosis). Vessels are hyperemic.

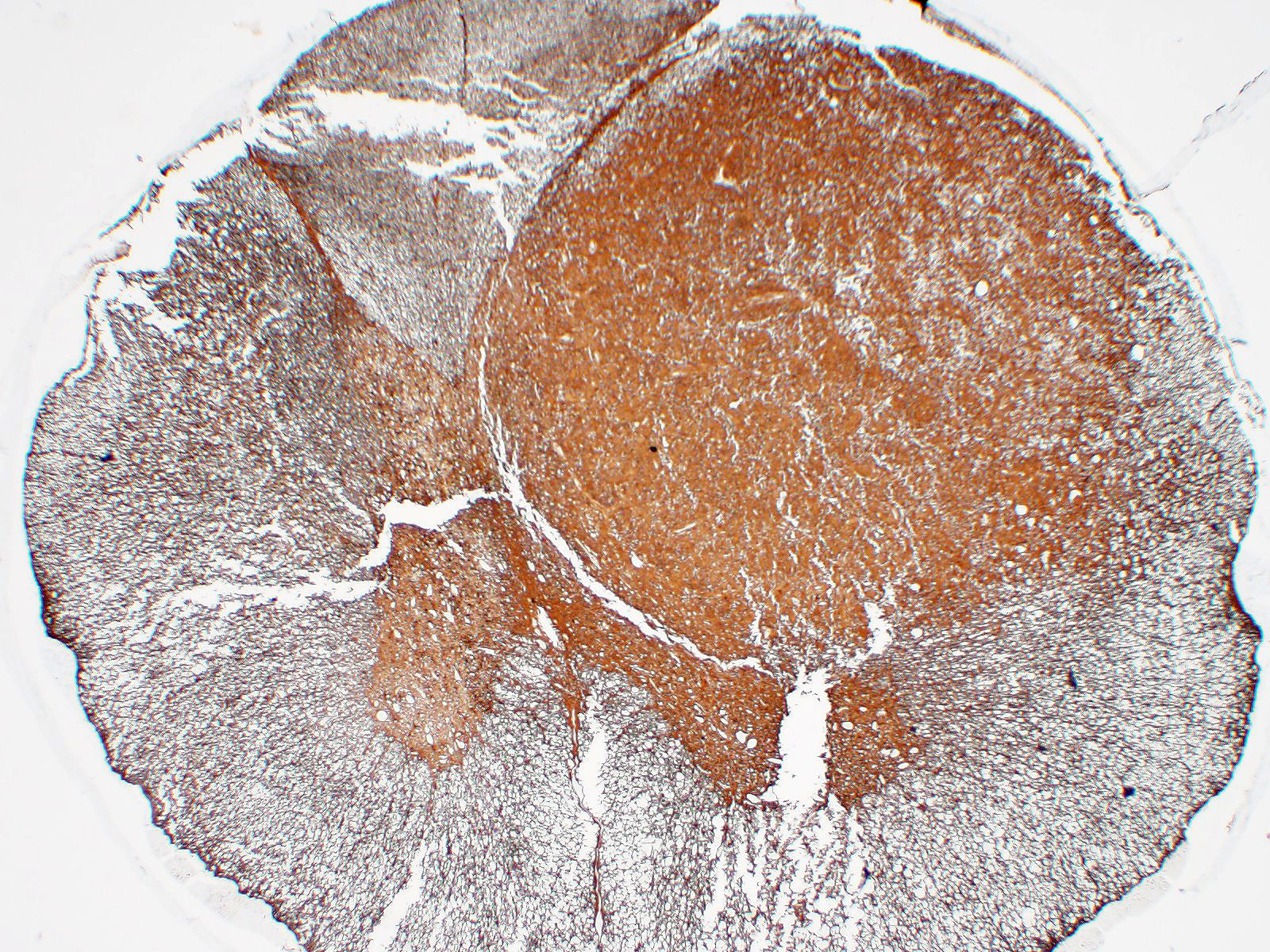

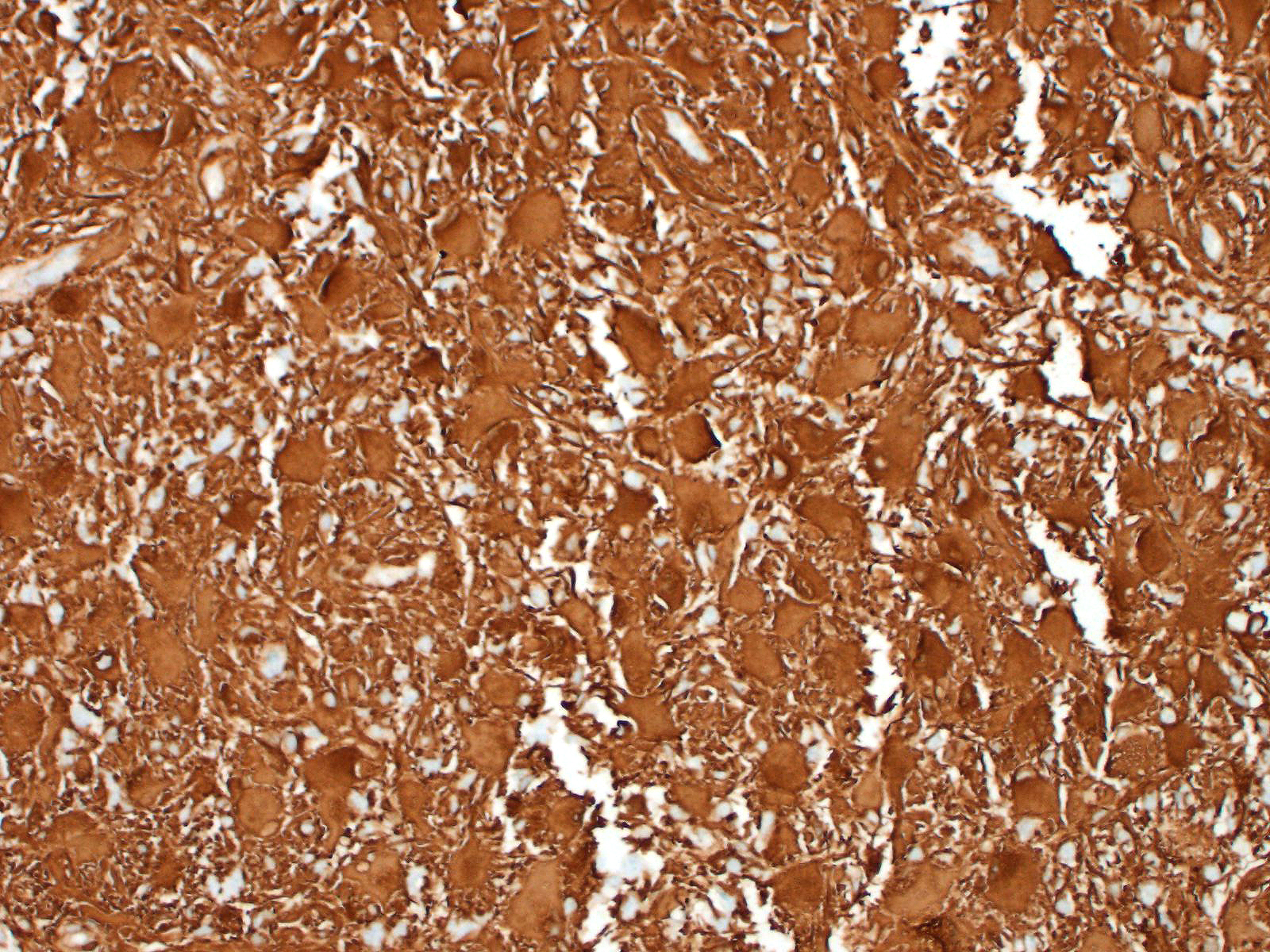

Immunohistochemistry: neoplastic cells are diffusely and strongly GFAP-positive, diffusely and moderately S100-positive; negative to CNPase.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Spinal cord. Gemistocytic astrocytoma, grade II

Contributor’s Comment:

Gliomas are primary neoplasms of the central nervous system originating from glial cells.18 Astrocytomas are common in dogs, whereas they are rare in cats. In cats, astrocytomas represent about 2.8% of intracranial neoplasms and 3.5% of spinal ones; the most common tumors of the spinal cord in cats are lymphoma and osteosarcoma.1,8,18 The most frequent location of astrocytomas in cats, according to the literature, is telencephalon, with rarer reports in the brainstem, cerebellum and spinal cord.8,9,12,18

Astrocytomas have variable macroscopic appearance, although their presence might be hard to assess grossly. They can be firm, palpable masses, ranging from white to gray, with ill-defined borders and possible areas of necrosis, especially with larger and more malignant tumors.3

Histologically, astrocytomas are neuroepithelial tumors classified in different histological subtypes which correlate to the grade. Based on the 2007 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous system, there are:

- Low-grade astrocytomas (grade I), with the variants fibrillary astrocytoma, protoplasmic astrocytoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma;

- Medium grade astrocytomas (grade II), with the gemistocytic variant;

- Anaplastic astrocytomas (grade III);

- High-grade astrocytomas (grade IV) or glioblastoma.3,6

Low-grade astrocytomas are mostly scarcely or moderately cellular, unencapsulated, expansile, with round to oval neoplastic cells replacing the pre-existing tissue. On the other hand, the medium grade astrocytomas usually are more densely cellular, showing more nuclear atypia. Anaplastic astrocytomas are characterized by cells with the greater extent of atypia and higher mitotic index. In high-grade astrocytomas there are frequent areas of haemorrhages and necrosis, around which neoplastic cells are pseudopalisading. Proliferation of the endothelium of blood vessels is present. In this entity high pleomorphism and atypia of the neoplastic cells are expected.3

Alongside the well differentiated astrocytomas reported in cats, the rarer subtypes eg. pilocytic astrocytoma, granular cell astrocytoma, angiocentric astrocytoma and anaplastic gemistocytic astrocytoma are also described.8,9,15,18 There are few reports of gemistocytic astrocytoma in cats. Gemistocytic astrocytoma is considered a medium-grade (grade II) tumor that is histologically characterized by the prevalence of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric oval nuclei (gemistocytic cells).3 Nevertheless, in human pathology gemistocytic astrocytomas are no longer recognized as a histological subtype but rather as a pattern (“gemistocytic tissue pattern”), according to 2021 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system.7 A threshold of 20% gemistocytes in the neoplastic population is suggested to adopt this definition.7

On immunohistochemistry, neoplastic cells in gemistocytic astrocytomas are immunoreactive for glial fibrillar acidic protein (GFAP), S100, vimentin, whereas they do not stain for CNPase and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), in contrast to oligodendrolioma or glioblastoma, respectively.1,3 Variable immunoreactivity for p53 was also described in one study, suggesting a possible abnormal biological behavior of this protein in the pathogenesis of feline astrocytoma.1

We classified the lesion we submitted as a gemistocytic astrocytoma taking into consideration the prevalence of gemistocytic cells observed on histology in association with the immunohistochemical positivity for S100 and GFAP and negativity for CNPase.

Contributing Institution:

San Marco Veterinary Clinic and Laboratory

Pathology division

Viale dell’Industria 3, 35030

Veggiano (PD), Italy

https://www.clinicaveterinariasanmarco.it/

JPC Diagnosis:

Spinal cord: Gemistocytic astrocytoma.

JPC Comment:

A recent Vet Pathol review article by Rissi details the clinical, pathologic, diagnostic, and behavioral features of primary central nervous system neoplasms in cats. Most intracranial neoplasms in cats are primary brain tumors, and the most common primary brain tumor is the meningioma, representing 60% of all intracranial tumors and 85% of all primary brain tumors. 12 Gliomas are the second most common primary CNS tumor of the cat but, in the spinal cord and vertebral column, gliomas are slightly more common (8%) than meningiomas (7%).12 The most commonly reported type of glioma in the cat is the astrocytoma; ependymoma and oligodendroglioma are reported at lower rates.12

Astrocytomas have variable staining for GFAP and OLIG-2, whereas oligodendrogliomas have strong labeling for OLIG-2 and variable reactivity for GFAP.13 Round cell markers may also be useful to rule out lymphoma in neoplasms that lack OLIG-2 staining, as lymphoma is the most common spinal cord tumor of cats.13 Recently, Elbert and Rissi reported on doublecortin immunolabeling in 11 feline gliomas. Doublecortin (DCX) is a protein of neuronal precursor cells. 13 DCX expression along the periphery of invasive human gliomas is suggestive of more invasive behavior. 13 In this study on feline gliomas, DCX was expressed in all 4 astrocytomas, with more intense staining along the margins of the neoplasms. 13 Neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN), expressed by mature neurons, was negative in all four astrocytomas of this study. 13

Gliosarcoma is a rare subtype of the grade IV astrocytoma (glioblastoma), and the first documented case in a cat was reported by Alvarez et al in 2019. Gliosarcomas are composed of bimorphic cell populations: a glial component and a sarcomatous component; both components are thought to arise from a common progenitor cell due to their similar genetic alterations.2 This case was in a 5-year-old cat with 1.5-year history of mild neurologic signs that acutely progressed, and a gliosarcoma was discovered in the septum pellucidum. Within the glial component, neoplastic cells histologically resembled astrocytes and were positive for GFAP and negative for OLIG-2.2 This case also contained all four types of structures of Scherer, which are histologic features of invasiveness in glial tumors.2 Types of Scherer structures include spread within the subpial space, perivascular infiltration, and perineuronal and perivascular satellitosis.2

The glioma entity was first described over 200 years ago, and several notable pathologists have contributed to our knowledge of the entity. Rudolf Virchow coined the term glioma and provided the first histologic description of the neoplasm,11 and Howard Tooth, Percival Bailey, and Harvey Cushing later expanded the knowledge of glioma histology. German pathologist Hans Joachim Scherer (1906-1945), the namesake for Scherer structures, also conducted extensive landmark research on gliomas.11 One of the many observations made by Scherer that shape our understanding of gliomas is the pseudopalisading of neoplastic cells around areas of necrosis in glioblastoma multiforme (high grade astrocytoma).17 As a researcher in Germany during the first half of the 20th century, Scherer’s work was both influenced and interrupted by Nazi activities and World War II. After being arrested by the Gestapo in 1933, Scherer fled to Belgium, where published numerous studies on human gliomas while employed at the Institute Bunge in Antwerp.10 In 1941, the German military ordered Scherer to return to Germany, and he began working at the Neurologic Institute in Breslau (now Poland).10 There, he conducted post-mortem examinations on at least 209 euthanized children, most with neurologic disabilities.5 Whether his work in this program was voluntary or conducted under coercion is still unknown, but his prior arrest, his exodus from Germany after Hitler rose to power, and personal accounts from his acquaintances suggest that he was not sympathetic to the Nazi party.16 Scherer died in 1945 in a railway station attacked during one of the last Allied bombings.11

Readers are encouraged to review Case 1, Conference 7, 2021-2022, a grade IV astrocytoma in the dog. The contributor and conference comments provide an excellent review of features of canine astrocytoma, including a recently published grading scheme for canine gliomas.

References:

- Aloisio F, Levine JM, Edwards JF. Immunohistochemical features of a feline spinal cord gemistocytic astrocytoma. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008 Nov;20(6):836-8.

- Alvarez P, Wessmann A, Pascual M, Comas O, Pi D, Pumarola M. Cerebral gliosarcoma with perivascular involvement in a cat. JFMS Open Reports. 2019; 5(2): 1-6.

- Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous System. In: Grant Maxie M, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, USA: Elsevier. 2016; 250-406.

- Elbert JA, Rissi DR. Doublecortin immunolabeling and lack of neuronal nuclear protein immunolabeling in feline gliomas. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2022; 34(4):757-760.

- Kleiheus P. Reply to Marc Scherer. Brain Pathol. 2013; 23(4): 488.

- Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007; 114(2):97-109.

- Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021 Aug 2;23(8):1231-1251.

- Marioni-Henry K. Tumors affecting the spinal cord of cats: 85 cases (1980–2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008; 232: 237–243.

- Murthy VD, Liepnieks ML, Roy MA, et al. Diagnosis and clinical outcome following surgical resection of an intracranial grade III anaplastic gemistocytic astrocytoma in a cat. JFMS Open Rep. 2020; 6(2): 2055116920939479.

- Peiffer J, Kleiheus P. Hans-Joachim Scherer (1906-1945), pioneer in glioma research. Brain Pathol. 1999; 9(2): 241-245.

- Reuter G, Lombard A, Molina ES, Scholtes F, Bianchi E. Hans Joachim Scherer: an under-recognized pioneer of glioma research in Belgium. Acta Neurol Belg. 2021; 121(4): 867-872.

- Rissi DR. Feline glioma: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Feline Med Surg. 2017; 19:1307–1314.

- Rissi DR. A review of primary central nervous system neoplasms of cats. Vet Pathol. Online First.

- Rissi DR, McHale BJ, Armién AG. Angiocentric astrocytoma in a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2019; 31(4): 576-580.

- Sant’Ana FJ. Pilocytic astrocytoma in a cat. Vet Pathol. 2002; 39: 759–761.

- Scherer M. Some comments on the paper: Hans-Joachim Scherer (1906-1945), a pioneer in glioma research. Brain Pathol. 2013; 23(4):485-487.

- Stoyanov GS, Petkova L, Dzenkov DL.Hans Joachim Scherer and His Impact on the Diagnostic, Clinical, and Modern Research Aspects of Glial Tumors. 2019; 11(11): e6148.

- Troxel MT. Feline intracranial neoplasia: retrospective review of 160 cases (1985–2001). J Vet Intern Med. 2003; 17: 850–859.