Conference 15, Case 2:

21-year-old, intact male, rhesus macaque, (Macaca mulatta)

History:

This Indian-origin rhesus macaque has a history of oral and dental disease. Approximately four months prior to necropsy, heavy dental calculus, gingivitis, and loose teeth necessitated cleaning and extraction of multiple teeth. The extraction sites did not heal despite several therapies. Radiographs revealed a retained tooth fragment and an oronasal fistula. The dental fragment was removed and this surgical site also failed to heal. Incisional biopsies of the palatine mucosa and buccal mucosa were collected and microscopic evaluation revealed an ameloblastoma. Euthanasia was elected.

Gross Pathology:

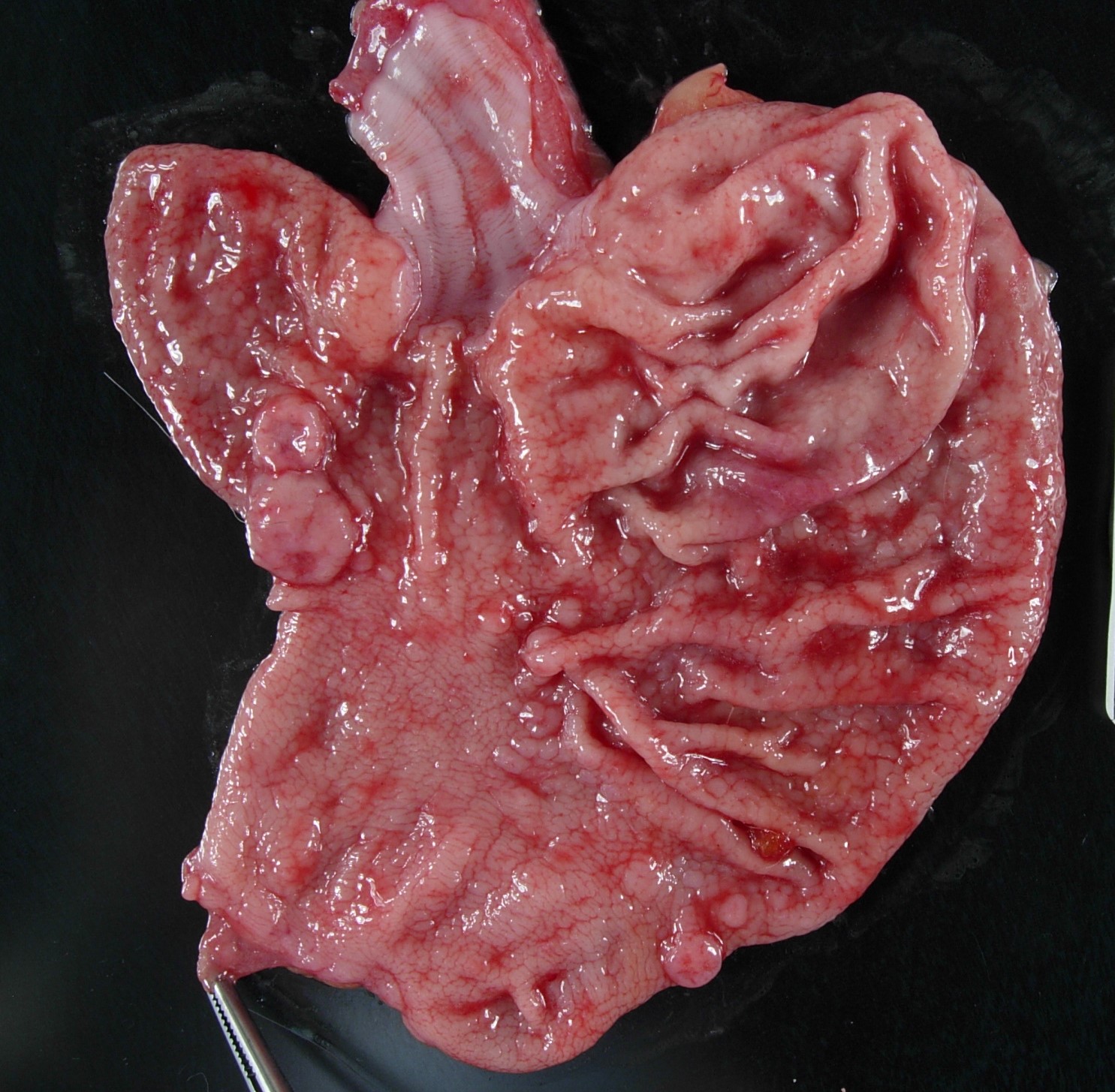

Well-muscled, aged, intact male rhesus monkey in excellent nutritional condition (body weight 11.8, body condition score 3/5). Expanding the buccal mucosa and gingiva adjacent to the dental extraction sites and invading the hard palate is a pale, white, glistening neoplasm that measures up to 3.6 cm in greatest dimension (tissue not submitted). The gastric mucosa is diffusely and moderately thickened and exhibits a cobblestone pattern. Round, fleshy, dark pink, sessile tumors protrude from the gastric mucosa into the lumen and measure up to 1 cm in diameter (fig. 1). There are multiple outpouchings of the intestinal mucosa (diverticulosis). The free margins of the left atrioventricular valve are minimally thickened and nodular (endocardiosis). The aortic intima is multifocally thickened with raised white to yellow irregular plaques (atherosclerosis). Few cysts measuring up to 0.2 cm in diameter are present in both renal cortices.

Laboratory Results:

N/A.

Microscopic Description:

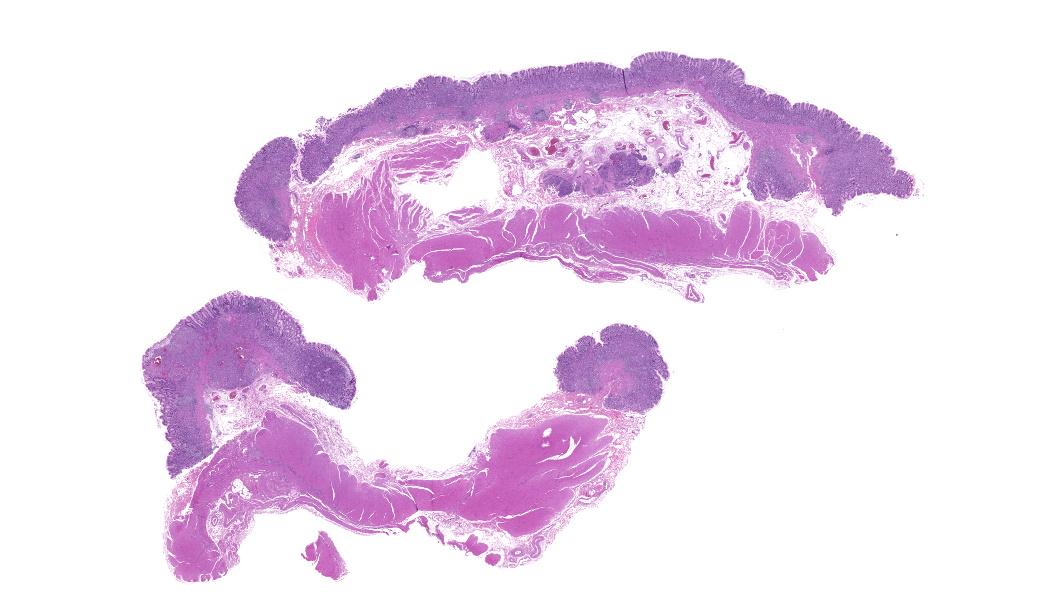

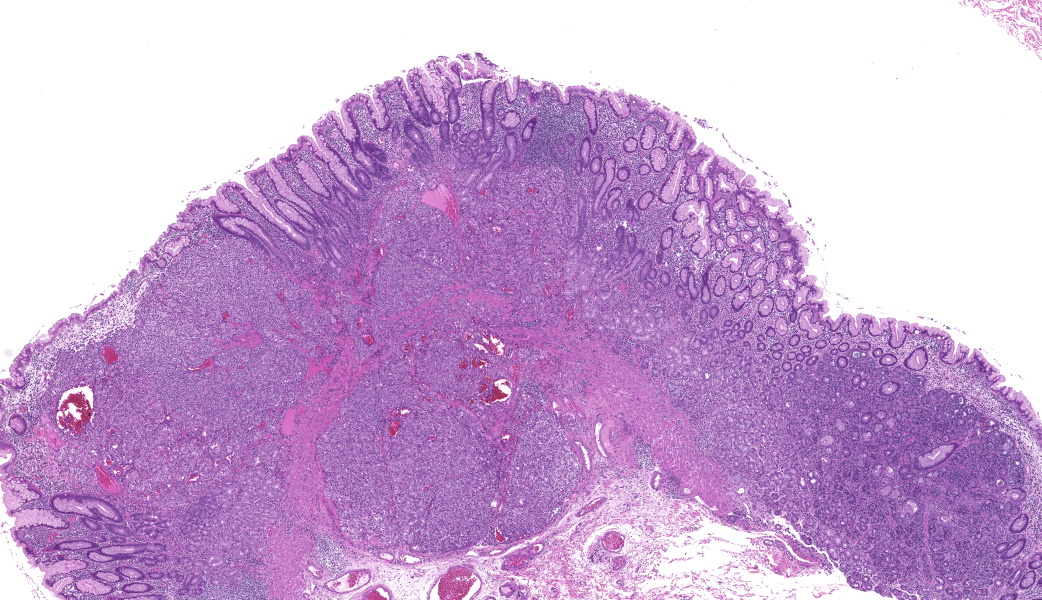

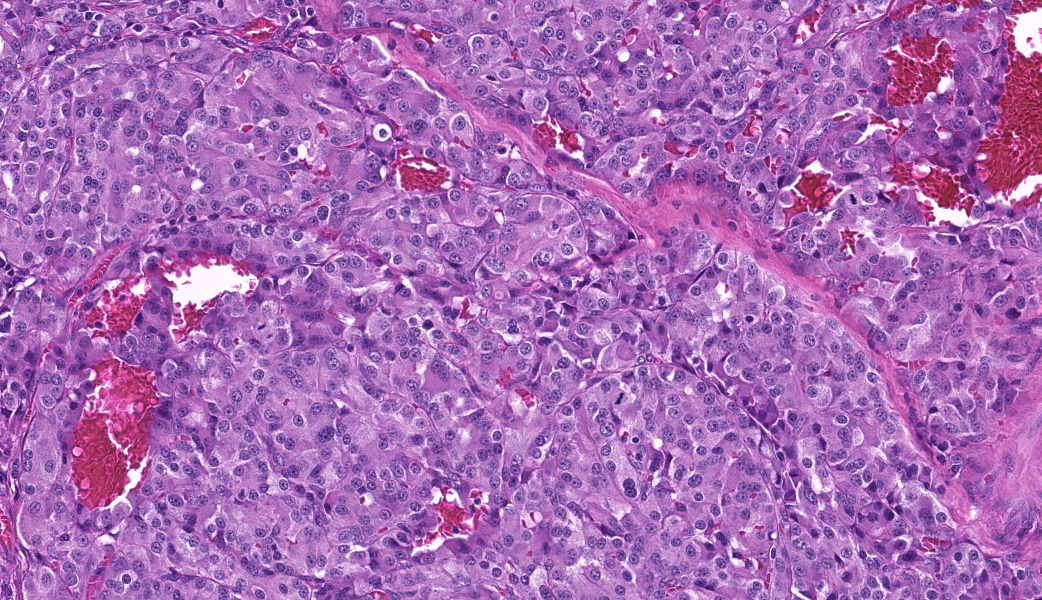

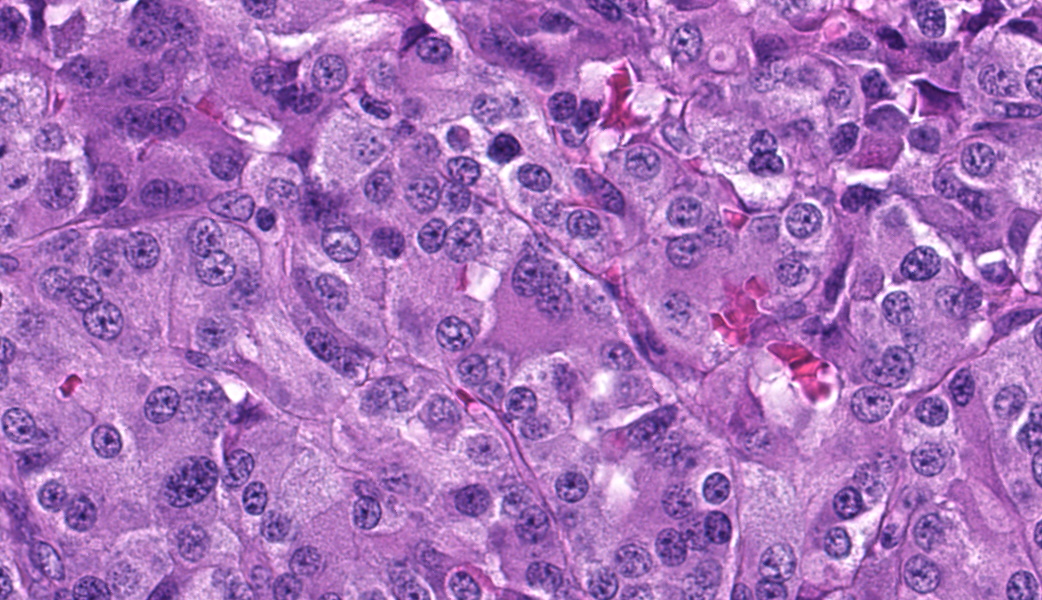

Focally elevating the attenuated, intact superficial epithelium and expanding the gastric mucosa and submucosa and displacing gastric glands are multiple, coalescing, partially encapsulated multilobulated neoplasms composed of nests and packets of neoplastic cells supported by a fine fibrovascular stroma. Some rosette formation with luminal blood is present and in other areas, there is pseudoglandular formation with entrapment of glands and foveolar epithelium. Neoplastic cells are round to polygonal with variably indistinct cell borders and amphophilic to pale eosinophilic, lightly granular cytoplasm. Nuclei are round to oval with usually one distinct nucleolus and finely dispersed to coarsely stippled chromatin. Occasionally, neoplastic cells contain up to three nuclei. There is moderate to marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis and less than one mitotic figure/HPF. Submucosal vascular invasion is present. There is proprial edema overlying mucosal nodules. Moderate numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes, fewer eosinophils, and occasional macrophages, neutrophils, and Mott cells are present within the lamina propria and multifocally traverse the muscularis mucosa and extend to the submucosa. Multifocally, there is foveolar hyperplasia and dysplasia and expansion of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. The submucosa is variably edematous and lymphatic vessels are ectatic.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

1. Stomach: Neuroendocrine tumor (carcinoid), multiple, mucosa and submucosa with vascular invasion.

2. Stomach: Gastritis, plasmacytic, lymphocytic, few eosinophils and occasional macrophages, neutrophils, and Mott cells, diffuse, moderate, with multifocal, mild foveolar hyperplasia and dysplasia.

Contributor’s Comment:

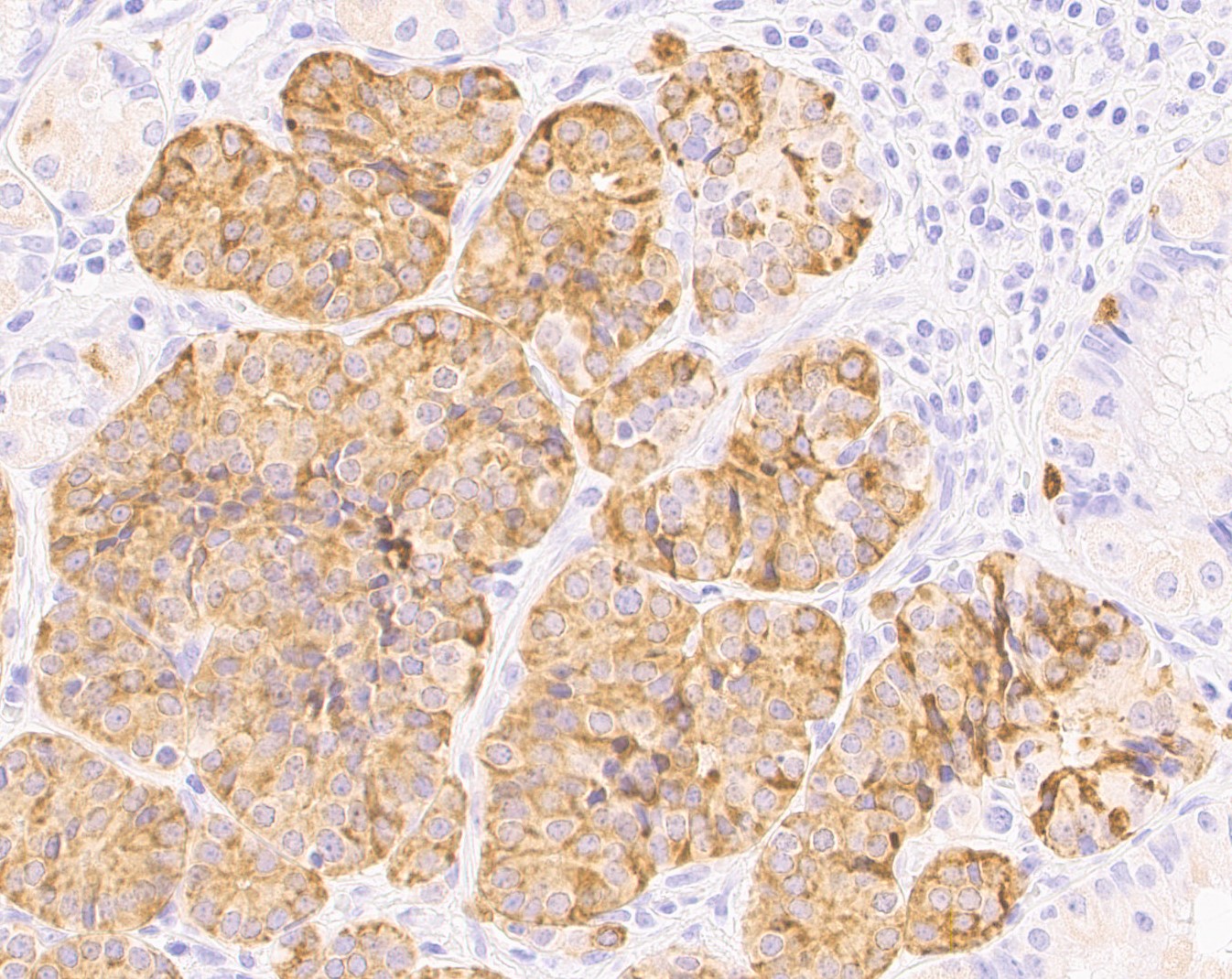

This macaque had multiple malignant gastric carcinoids. Vascular invasion was evident in the vasculature of the submucosa; however, regional or distant metastases were not identified on microscopic examination of remaining tissues. A Churukian-Schenk histochemical stain highlighted argyrophilic granules within neoplastic cells, and neoplastic cells were also immunoreactive for chromogranin A, a neuroendocrine marker (fig. 3). The histologic features, immunohistochemical and special histochemical staining of these neoplasms were consistent with the diagnosis of carcinoids.

Gastric carcinoid tumors arise from the neuroendocrine cells of the mucosa and are rare in this large nonhuman primate colony. A retrospective review of pathology records spanning the last six decades at the center revealed only one other case of gastric carcinoid in an adult female rhesus macaque. A single, malignant carcinoid that exhibited lymphatic invasion was diagnosed. During a recent virtual conference, multiple neuroendocrine gastric neoplasms were reported in an aged rhesus macaque. (Ruivo, P. 2023, April 25. Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumor, NHPRC Virtual Slide Conference, California National Primate Research Center, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.) A review of the literature revealed rare reports of carcinoid tumors involving sites other than the stomach in nonhuman primates and included hepatic carcinoid tumors in a baboon (Papio sp.) and a Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata), the lung of a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), and the duodenum of a cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis).2,4,5,7

In humans, gastric carcinoids may be solitary or multiple and are placed in three categories. Type 1 presents with multiple, slow growing tumors. Local and distant metastases are rare. The pathogenesis is thought to involve chronic atrophic gastritis where there is parietal cell loss resulting in achlorhydria which causes excessive release of gastrin from G cells. Hypergastrinemia stimulates tumor formation and growth. Type 2 carcinoids are associated with gastrinomas; hypergastrinemia occurs because of a primary increase in gastric acid production. These carcinoids are associated with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and generally occur in patients with MEN type I. Tumors are small, multiple, slow growing, and metastasize more often when compared to type 1. Type 3 carcinoids are usually solitary, rapidly growing, and exhibit frequent metastases to regional lymph nodes and the liver. They are not associated with chronic atrophic gastritis, gastrinomas, or MEN 1, and may be composed of multiple kinds of endocrine cells. Blood gastrin levels are normal. Atypical carcinoid syndrome characterized by flushing may be seen.13 The classification scheme for human carcinoids could not be applied in this case. There were multiple tumors in this macaque. The functionality of the tumors is unknown. Clinical signs such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and sustained weight loss consistent with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome were not reported. Chronic, atrophic gastritis was not evident on microscopic examination.

Spontaneous gastric neuroendocrine tumors are rare in domestic veterinary species.1,12 Other species reported with spontaneous gastric neuroendocrine tumors include a ferret (Mustela putorius furo), an aged Sprague-Dawley Rat, and 7/135 striped field mice (Apodemus agrarius).3,8,9 At least two species are an exception to the rarity of gastric carcinoids noted here. A retrospective study of neoplasia in the alimentary tract of bearded dragons (Pogona spp) reported that of 26 gastric neoplasms, 16 were neuroendocrine carcinomas. Metastases were observed in 14 of these cases most often to the liver and kidney reflecting an aggressive biologic behavior.6 In another study involving bearded dragons, 5 of 5 tumors demonstrated immunolabeling for somatostatin.10 Spontaneous gastric carcinoids were diagnosed on necropsies of 600 African rodents, Praomys (Mastomys) natalensis housed in a closed colony. Two-thirds of the aged males and one-third of the aged females were affected and exhibited regional and distant metastases.11

Contributing Institution:

Pathology Services Unit

Division of Animal Resources and Research Support

Oregon National Primate Research Center

505 NW 185th Avenue

Beaverton, OR 97006

https://www.ohsu.edu/onprc

JPC Diagnoses:

1. Stomach: Neuroendocrine tumor (carcinoid).

2. Stomach: Gastritis, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, diffuse, moderate.

JPC Comment:

Another fantastic write-up! This case made for highly educational discussion on a classic entity. Many thanks to the contributor for providing this case, along with chromogranin A IHC images that supported the diagnosis. Chromogranin A is a great IHC to use for these types of cases, as it immunoreacts with dense granules in neuroendocrine cells. Other great IHC options for neuroendocrine neoplasms include synaptophysin or insulinoma-associated protein-1 (INSM-1).

Most participants were initially split on this diagnosis based on the H&E alone, with some confidently diagnosing a carcinoid and others wondering about an adenocarcinoma due to the formation of what appeared to be acini. The presence of nests, packets, pseudoglandular formation, and rosettes in the neoplasm’s pattern should clue the pathologist into the possibility that this is a neuroendocrine neoplasm rather than an epithelial one. Participants engaged in spirited debate on the presence of vascular invasion in this digital-only case. Most participants were not sold on it and interpreted the nucleated cells within blood vessels as either histiocytes or other nucleated circulating cells. Ultimately, IHC would have been necessary to confirm this. As such, vascular invasion was left out of the JPC’s morphologic diagnosis. Participants did agree that the gastritis should receive its own morphologic diagnosis, as most did not think it was simply a result of the neoplasm due to the prevalence of gastritis, enteritis, and colitis seen in captive nonhuman primates.

Although this case did not classify as such, diagnostic criteria for gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma (gNEC) were reviewed as part of the discussion due to the invasion into the underlying stroma seen on the slide. This feature should have put gNEC on any initial differentials list. Important criteria for gNEC include a single, large, ulcerated mass, usually in the cardia or antrum of the stomach, with poorly differentiated cells arranged in sheets or nests with extensive necrosis.14 gNEC usually has a spicy mitotic rate (>20 per 1mm2) and an high Ki67 proliferation index (always >20% and commonly above 70%).14 The neoplasm in this case was not classified as a gNEC as, although it was invading into the submucosa, it did not have a high mitotic rate, was multifocal, and was not associated with necrosis.

Other gastric and intestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms were reviewed, along with a few important syndromes to keep in mind that are commonly associated with them. For example, gastrinomas that secrete gastrin can do so in such amounts that they stimulate hypersecretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, causing gastritis, esophagitis, and/or gastric and duodenal ulceration. This is known as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Additionally, carcinoids can be seen in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia-1 Syndrome. MEN1 results from an autosomal dominant inactivating mutation of the menin gene. Normally, this gene produces menin, a scaffold protein that functions as a critical tumor suppressor, especially in endocrine glands, where it regulates cell growth, division, DNA repair, and apoptosis.9 The diagnosis of MEN1 in humans requires either demonstration of the genetic mutation OR least two of the following: parathyroid gland tumor, pituitary tumor, and either gastric, enteric, or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pancreatic are the most common).12 Alternatively, in humans, MEN1 can also be diagnosed with any one of the listed neoplasms along with demonstration that the affected person also has a first-degree relative with confirmed MEN1. Clinically, primary hyperparathyroidism is the first and most common manifestation of MEN1.12 Other final points of discussion included the classification of gastric carcinoids (GNETs) into three different types, each of which was kindly covered in the contributor’s comment.

References:

- Albers TM, Alroy J, McDonnell JJ, Moore AS. A Poorly Differentiated Gastric Carcinoid in a Dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1998;10(1):116-118.

- Aloisio, F, Dick EJ, Hubbard, GB. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in a baboon (Papio sp.). J Med Primatol. 2009;38:23-26.

- Bousquet T, Bravo-Araya M, Davies JL. Gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma (carcinoid) in a ferret (Mustela putorius furo). Can Vet J. 2022;63(11):1109-1113.

- Giddens WE, Dillingham LA. Primary Tumors of the Lung in Nonhuman Primates; Literature Review and Report of Peripheral Carcinoid Tumors of the Lung in a Rhesus Monkey. Vet Pathol. 1971;8(5-6):467-478.

- Hirata A, Miyamoto Y, Kaneko A, Sakai H, Yoshizaki K, Yanai T, Miyabe-Nishiwaki T, Suzuki J. Hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in a Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata). J Med Primatol. 2019;48(2):137-140.

- LaDouceur EB, Argue A, Garner MM. Alimentary Tract Neoplasia in Captive Bearded Dragons (Pogona spp). J Comp Pathol. 2022;194:28-33.

- Lau DT, Spinelli JS. A spontaneous carcinoid tumor in a cynomolgus monkey, Macaca fascicularis. Lab Anim Care. 1970;20(6):1145-8.

- Majka JA, Sher S. Spontaneous gastric carcinoid tumor in an aged Sprague-Dawley rat. Vet Pathol. 1989;26(1):88-90.

- Matkar S, Thiel A, Hua X. Menin: a scaffold protein that controls gene expression and cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(8):394-402.

- Oh SW, Chae C, Jang D. Spontaneous gastric carcinoid tumors in the striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius). J Vet Med Sci. 1997;59(8):703-6.

- Ritter JM, Garner MM, Chilton JA, Jacobson ER, Kiupel M. Gastric Neuroendocrine Carcinomas in Bearded Dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Veterinary Pathology. 2009;46(6):1109-1116.

- Singh G, Mulji NJ, Jialal I. Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Snell KC, Stewart HL. Spontaneous diseases in a closed colony of Praomys (Mastomys) natalensis. Bull World Health Organ. 1975;52(4-6):645-50.

- Uccella S, La Rosa S. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the stomach. Update on diagnostic criteria, classification, and prognostic markers. Virchows Arch. Published online November 22, 2025.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:105-106.

- Wardlaw R, Smith JW. Gastric carcinoid tumors. Ochsner J. 2008;8(4):191-6.