Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 12, Case 3

Signalment:

2 year intact female cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis)History:

Gross Pathology: No gross lesions were noted at the time of necropsy.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

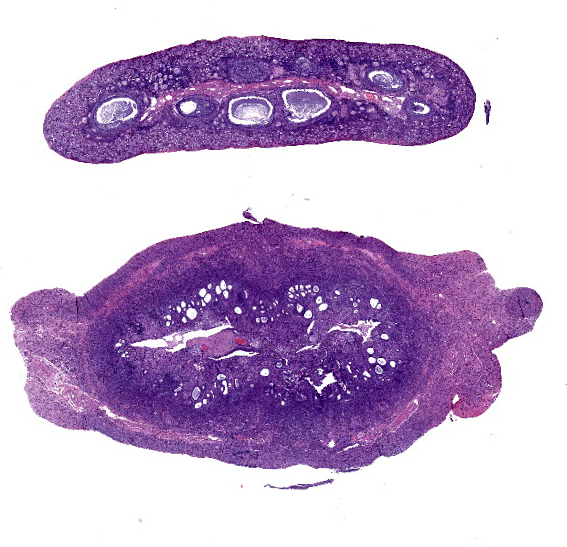

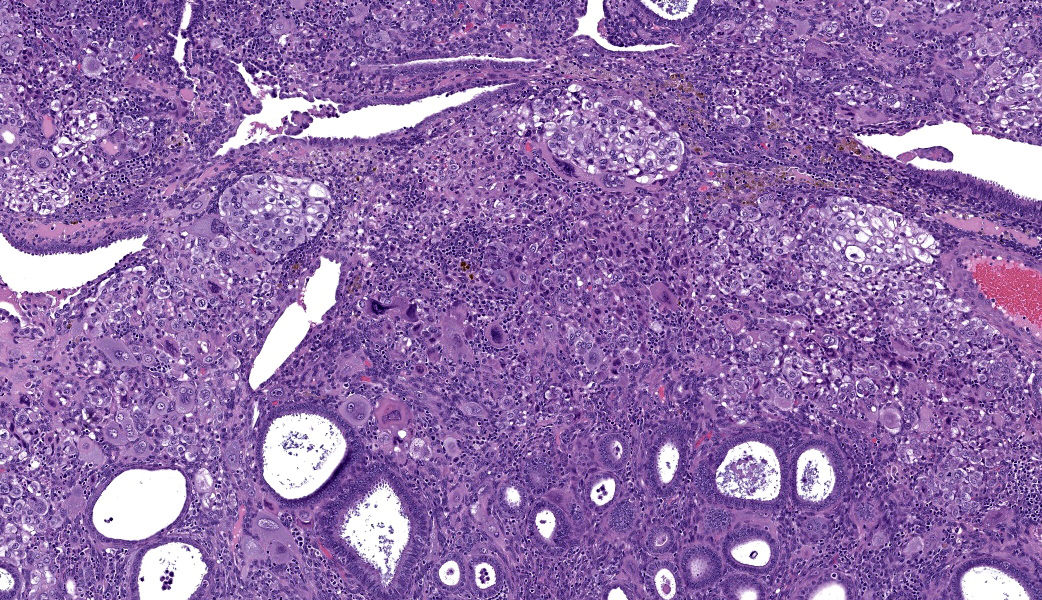

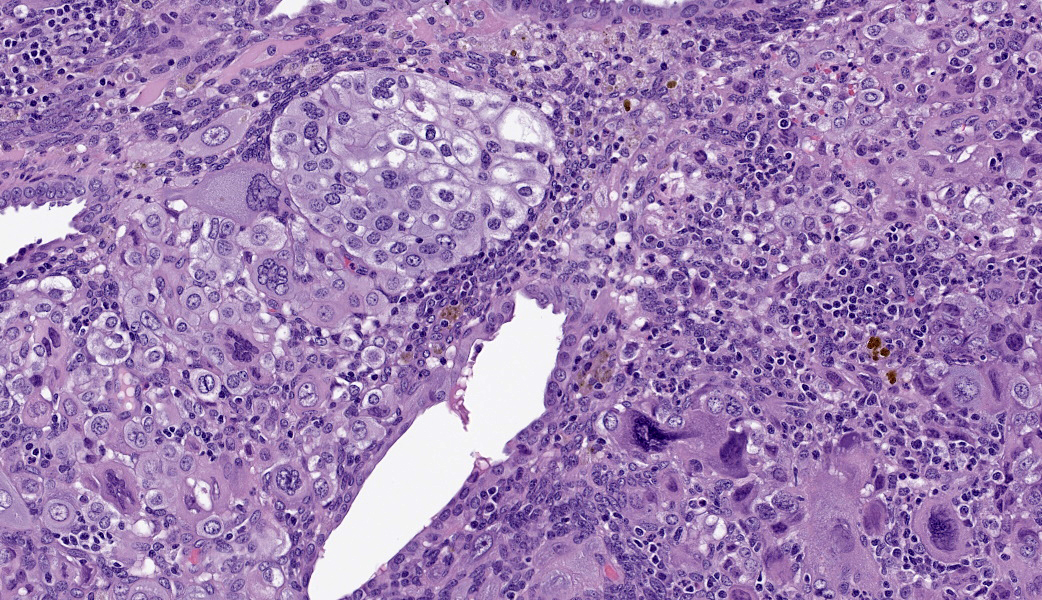

Uterus: Regionally effacing the endometrium, displacing and disrupting the normal glandular and stromal architecture, is a poorly circumscribed, nonencapsulated, infiltrative proliferation of highly pleomorphic round to polygonal neoplastic cells arranged in sheets. The neoplastic proliferation is composed of a biphasic population of uninucleate or multinucleate cells with distinct cell borders, moderate to marked amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and large round vesiculate to finely stippled nuclei and 1-4 variably prominent nucleoli, consistent with a trophoblastic (cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts, respectively) lineage. There are 2 mitotic figures in 10 high power fields (400x). Moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells are scattered throughout the adjacent endometrial stroma and outer myometrium. Dilated endometrial glands occasionally contain a variable amount of eosinophilic amorphous to basophilic flocculant debris and few macrophages or lymphocytes. Regional erosion of endometrial epithelium is present. The ovary lacks corpora lutea, consistent with sexual immaturity.Slides not provided:

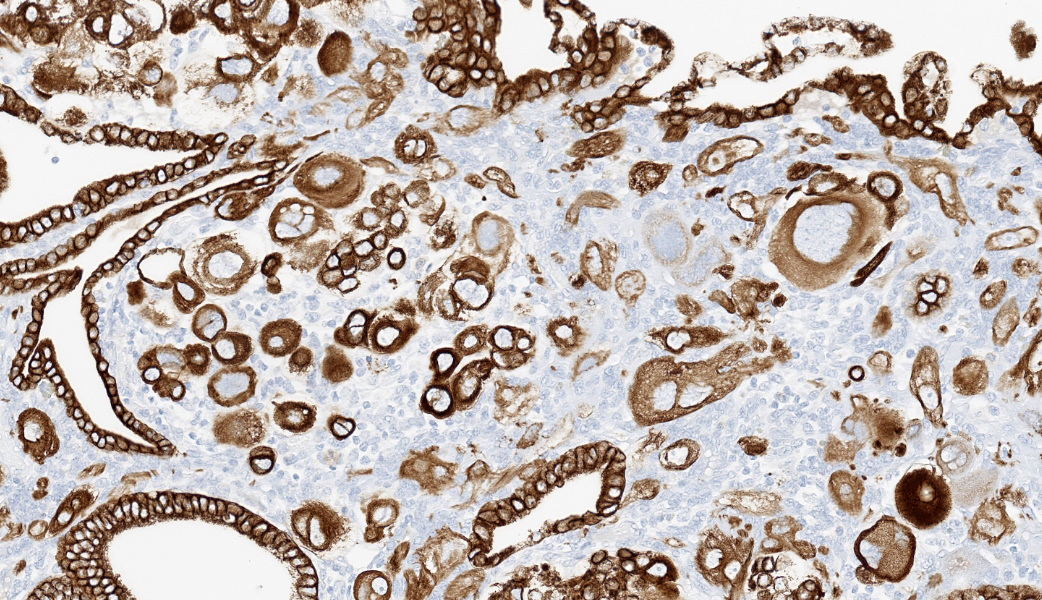

Immunohistochemistry on the uterine neoplasm is performed using anti-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), anti-pancytokeratin AE1/AE3, anti-human placental lactogen (huPL), anti-p63, anti-CD10, anti-placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAPH), anti-progesterone receptor (PR), anti-estrogen receptor α (ERα), and anti-Ki67 antibodies and is visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine or Fast Red as a chromogen. Occasional neoplastic cells with high degrees of atypia express cytoplasmic labeling for hCG. Neoplastic cells have strong cytoplasmic and membranous labeling for pancytokeratin AE1/AE3. Labeling for huPL and CD10 demonstrates rare neoplastic cells expressing moderate to strong cytoplasmic immunolabeling; however, the majority of neoplastic cells are negative. Few neoplastic cells have weak nuclear p63 labeling. Labeling for Ki67 demonstrates moderate to high numbers of proliferative neoplastic cells regionally. Overall, PR and ERα expression is limited due to the immature age of the animal, but is present in the expected locations in the endometrial stroma and glandular epithelium, and absent in the neoplastic population. Neoplastic cells do not label for PLAPH. These immunohistochemical findings further support a diagnosis of choriocarcinoma.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Uterus: ChoriocarcinomaContributor's Comment:

Choriocarcinoma is a neoplasm of trophoblastic lineage that most often arises in women following normal or abnormal pregnancies.1 Diagnostic features include highly pleomorphic, polygonal to round cells with abundant cytoplasm that are both uninucleate (cytotrophoblast or intermediate trophoblast-like) and multinucleate (syncytiotrophoblast) cells, and often a high mitotic rate with metastasis. Morphologic features on histologic evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin-stained uterus from this sexually immature cynomolgus macaque were consistent with choriocarcinoma.In human medicine, choriocarcinoma falls under the umbrella entity of gestational trophoblastic disease. Other neoplasms in this entity include placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT) and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor (ETT). PSTTs are composed of a monomorphic population of large, pleomorphic cells derived from implantation-type intermediate trophoblasts. Most cells are uninucleate, but it is not uncommon to see occasional scattered multinucleate cells. ETTs arise from chorionic-type intermediate trophoblasts and present as nests, cords, or solid masses with a monomorphic population of small, round cells.1 Choriocarcinomas tend to have a distinct morphology compared to PSTT and ETT with the presence of uninucleate and multinucleate cells; however, a panel of immunohistochemical markers is commonly used to confirm diagnosis. Characterization with antibodies against hCG, pancytokeratin AE1/AE3, huPL, p63, CD10, PLAPH, and Ki67 provides further support for a diagnosis of choriocarcinoma. These immunohistochemical markers are helpful in distinguishing between PSTT, ETT, and choriocarcinoma (see table).5

Marker |

PSTT |

ETT |

Choriocarcinoma |

Lesion |

hCG |

+/- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

huPL |

+ |

+/- |

+/- |

Rare |

p63 |

- |

+ |

+/- |

Rare weak |

Pancytokeratin AE1/AE3 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

CD10 |

+/- |

- |

+/- |

Rare |

PLAPH |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Inhibin-α |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Not performed |

Ki67 Index |

Moderate |

Moderate |

High |

High |

This neoplasm has been reported in laboratory and domestic species and is noted in the International Harmonization of Nomenclature and Diagnostic Criteria (INHAND) for non-proliferative and proliferative lesions in non-human primates (NHP), mice, and rabbits.2-4 In women, non-gestational choriocarcinoma can occasionally arise in the ovary and have only rarely been reported as a primary tumor in the uterus.7 While non-gestational choriocarcinoma of the ovary has been reported in NHP, there are no published examples of a primary non-gestational choriocarcinoma of the uterus.

Spontaneous neoplasms in nonrodent species are rare in routine toxicology work due to the young age of animals used in nonclinical toxicity testing. Knowledge of spontaneous background lesions is necessary to distinguish from potential test article-related effects in any species.

Contributing Institution:

Charles River Laboratories – Mattawan, MIcriver.com

JPC Diagnoses:

Uterus: Choriocarcinoma.JPC Comment:

The contributor of this case provides a great overview of choriocarcinomas, their main differentials, and the common immunohistochemical profiles expected with these neoplasms in their comment. These topics covered much of what was discussed in conference for this case.The topic of the IHCs prompted a review of what each of the pertinent markers is for and what some of the IHC targets do physiologically. For example, choriocarcinomas are readily immunoreactive for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). In the body, hCG (or any of the species-specific CGs, for that matter), is produced by the placental trophoblasts (the cell of origin in choriocarcinoma) and stimulates the release of progesterone from the corpus luteum (CL) to maintain the pregnancy. Human placental lactogen (HPL) also functions as a marker for trophoblasts and is released by the placenta to, among other functions, stimulate growth of the mammary glands for lactation. CD10 marks endometrial stroma. Inhibin, released from granulosa cells (GC) to regulate production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), will be immunoreactive in granulosa cells (including in some neoplastic GC populations). Although choriocarcinoma is classified as a germ cell tumor, it is weakly to not at all immunoreactive for placental-like alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), which is a marker of germ cells. This is thought to be due to the neoplastic choriocarcinoma cells being less well-differentiated or potentially even de-differentiated compared to regular syncytiotrophoblasts, which are usually immunoreactive for PLAP.6 Lastly, p63, a member of the p53 “Guardian of the Genome” family of genes, will be immunoreactive in myoepithelial cells, squamous epithelial cells, and a few others. The table provided by the contributor provides an excellent resource for cross-comparison of IHC profiles between these in choriocarcinomas and their differentials.5

Choriocarcinomas are categorized as gestational (associated with pregnancy) or non-gestational (formed in the absence of pregnancy). Some participants were astutely able to deduce from the types of follicles found in the accompanying ovary on the slide that this was very likely a juvenile animal. This, coupled with the lack of gestational change to the uterus, led some to make the jump to a non-gestational choriocarcinoma. Kudos are due to the participants that managed to reason through those subtleties! As mentioned in the contributor’s comment, there are no published examples of primary non-gestational uterine choriocarcinoma in non-human primates.

While most participants were readily able to reach the diagnosis of “choriocarcinoma” from the H&E section in the absence of any immunomarkers,there was quite a bit of discussion on if this neoplasm would truly classify as a choriocarcinoma or if it would be considered “choriocarcinomatous differentiation” due to the young age of the animal. This is a term occasionally utilized in research settings, usually in the context of early choriocarcinoma-like changes seen with decidual reactions in NHPs. Although there was no evidence of decidual reaction in this case, we consulted with our JPC MD reproductive subspecialists, who agreed with the diagnosis of choriocarcinoma. The term “choriocarcinomatous change/differentiation” is not utilized in human medicine and is not listed in the NHP INHAND guide for terminology related to this neoplasm.3 As such, the JPC refrains from the usage of this term.

References:

- Benirschke K, Kaufmann P. Chapter 23: Trophoblastic Neoplasms. Pathology of the Human Placenta. 5th New York: Springer-Verlag; 2006.

- Bradley AE, Wancket LM, Rinke M, et al. International Harmonization of Nomenclature and Diagnostic Criteria (INHAND): Nonproliferative and Proliferative Lesions of the Rabbit. J Toxicol Pathol, 2021; 34(3 suppl): 183S-292S.

- Colman K, Andrews RN, Atkins H, et al. International Harmonization of Nomenclature and Diagnostic Criteria (INHAND): Non-proliferative and Proliferative Lesions of the Non-human Primate ( fascicularis). J Toxicol Pathol, 2021; 34(3 suppl): 1S-182S.

- Dixon D, Alison R, Bach U, et al. Nonproliferative and Proliferative Lesions of the Rat and Mouse Female Reproductive System. J Toxicol Pathol, 2014; 27(3-4 suppl): 1S-107S.

- Elmore SA, Carreira V, Labriola CS, et al. Proceedings of the 2018 National Toxicology Program Satellite Symposium. J Toxicol Pathol, 2018; 46(8): 865-897.

- Lösch A, Kainz C. Immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of the gestational trophoblastic disease. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996;75(8):753-6.

- Maesta I, Michelin OC, Traiman P, Hokama P, Rudge MVC. Primary non-gestational choriocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: A case report. Gynecol Oncol, 2005; 98(1): 146-50.