Signalment:

Adult female intact chicken (

Gallus galls domestics), breed unknown.4-week history of respiratory illness in the flock, affecting up to 35 birds. Clinical signs include coughing and sneezing in a subset of birds. This patient was found deceased.

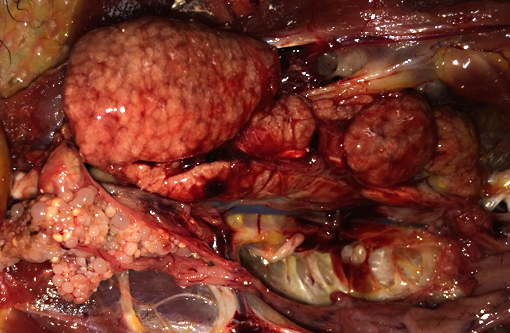

Gross Description:

A brown hen was submitted for necropsy in poor body condition with a

prominent keel due to marked atrophy of the pectoral muscles. There is a minimal amount of

internal body fat stores and subcutaneous fat is not present. The kidneys are diffusely enlarged

up to 3x normal, mottled pale to red in color, soft and friable, and bulge slightly upon cut section.

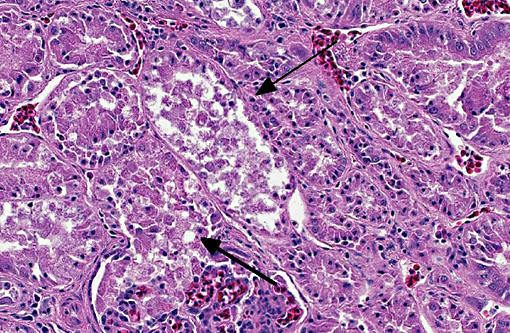

Histopathologic Description:

Diffusely throughout the renal parenchyma, there is widespread

degeneration and necrosis of the renal tubular epithelium characterized by swollen cells with

vacuolated cytoplasm and swollen nuclei (degeneration) or loss of cellular detail, eosinophilic

cellular debris and pyknotic nuclei (necrosis). Tubules have segmental loss of epithelium with

epithelial attenuation across bare basement membrane. Multifocally, small numbers of tubular

epithelial cells contain increased amounts of basophilic cytoplasm, have anisokaryosis and rare

mitotic figures (regeneration). Renal tubules are often ectatic, dilated up to 3x normal and

contain numerous epithelial cell casts, moderate numbers of heterophils, occasional granular

casts and/or amorphous, eosinophilic material (protein). The interstitium is expanded by

coalescing aggregates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and occasional heterophils. This

inflammatory infiltrate is accompanied by mild to moderate amounts of edema and fibrosis.

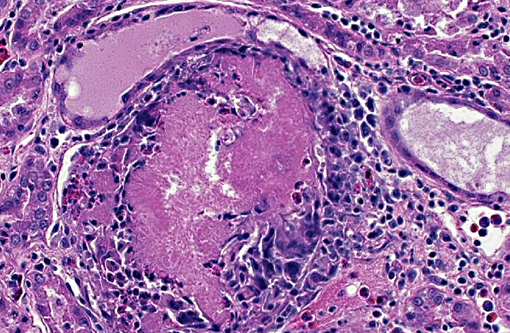

Additionally, renal tubules and glomeruli within the cortex are multifocally expanded and

replaced by sharp, radiating, eosinophilic crystalline deposits that range in size from 50-150

microns in diameter and are surrounded by moderate numbers of degenerate heterophils and

macrophages (urate tophi). Rarely, the parietal epithelium of Bowmans capsule is mildly

hypertrophic, characterized by plump, cuboidal epithelial cells that protrude into the glomerular

space.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Kidney: Tubulointerstitial nephritis, diffuse,

lymphoplasmacytic and heterophilic, chronic, severe with tubular necrosis, degeneration and

regeneration, urate tophi, cellular casts and tubuloproteinosis.

Lab Results:

Tracheal swab Avian Influenza real-time PCR Negative

Tracheal swab Infectious Bronchitis Virus real-time PCR Negative

Kidney Infectious Bronchitis Virus real-time PCR Negative

Condition:

Renal gout

Contributor Comment:

Tubulonephritis in chickens typically occurs as a result of infection

with either the nephrogenic strain of infectious bronchitis virus or avian nephritis virus.

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is a coronavirus with a non-segmented, positive-sense, singlestranded

RNA genome that infects all ages of chickens and results in major economic losses for

the poultry industry.(3,5) Clinical manifestations of IBV infection include respiratory disease,

reproductive disorders, and nephritis, with the latter presenting as a progression from respiratory

illness to clinical signs of renal failure such as excessive water intake, rapid weight loss and

diarrhea.(4) Infection with the nephrogenic strain of IBV initially results in viral replication in the

trachea, followed by spread to the kidney and infection of the renal tubular epithelium.(1,2,5)

Histologic lesions include interstitial polymorphonuclear inflammation, renal tubular

degeneration and necrosis, and uric acid precipitation, with tubular regeneration occurring in

surviving birds.(1,2,5) Detection of IBV infection is required for a definitive diagnosis, and is most

commonly achieved by virus isolation, reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RTPCR),

or serology.(3) In this case, RT-PCR was performed directly on a tracheal swab and on

RNA extracted from kidney, with negative results. However, as previously demonstrated, IBV

antigen is detected up to day 13 post-inoculation by immunohistochemistry, but not after,

suggesting clearance of the virus.(1,2) The 4-week span of respiratory illness with progression to

nephritis in this case may have allowed sufficient time for clearance of IBV from the trachea and

kidney prior to sampling, thus resulting in a negative result on RT-PCR. Furthermore, if the

primers used in the RT-PCR assay are not from conserved regions across all IBV strains, false

negatives may occur.(3) Tracheal or renal clinical samples may also can contain non-specific

inhibitors of the polymerase used in PCR, resulting in decreased sensitivity.(3) Together, these

points highlight the difficult challenge of obtaining a definitive diagnosis of IBV infection, even

in the presence of strongly supportive clinical signs and histopathologic findings. The clinical

history of respiratory illness in this flock, together with the gross and histologic lesions observed

in this adult chicken, are consistent with nephrogenic IBV infection. These findings underscore

the importance of recognizing distinct clinical signs and histopathological lesions so that an

accurate diagnosis is made, allowing for the institution of appropriate flock management.

Alternatively, avian nephritis virus (ANV) represents another possible differential for the renal

lesions observed in this case. Avian nephritis virus is a non-enveloped astrovirus with a single

stranded, positive sense RNA genome that affects young poultry and results in degeneration of

the renal tubules and interstitial inflammation, with formation of lymphoid follicles in later

stages.(6,8,9) Virus isolation, serology, and/or RT-PCR are the most common laboratory methods of

detecting ANV and a positive result is required for definitive diagnosis.(10) Although renal lesions

in this case may be consistent with ANV infection, this virus is not documented to cause

respiratory disease, such as that observed in this bird and the rest of the flock. Additionally,

lymphoid follicles seen in chronic cases of ANV infection were not observed in the kidney of

this case, despite 4-week duration of disease.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Kidney, tubules: Degeneration, necrosis, and regeneration, multifocal, moderate, with intratubular protein.Â

2. Kidney, cortex: Gouty tophi, multiple.

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides an overview of the two most likely etiologic

differentials in this case, and conference participants, whom are not privy to the provided clinical

history, added avian influenza and Newcastle disease as well. Herpesvirus and polyomavirus

may each also cause tubular necrosis in avian species, however, intranuclear inclusions would be

prominent in both instances.(4)

Much of the conference discussion was focused on whether the gouty tophi and the described

concentric amorphous structures, interpreted by most to be protein, were associated with the

infection. Urates are actively excreted by renal tubular epithelium, so it stands to reason that loss

of tubular epithelium can lead to urate accumulation and subsequent tophi formation.

Additionally, a sick bird as described in this case would likely be dehydrated which will further

exacerbate urate deposition. The gouty tophi formation was minimal in most sections, thus not

likely a significant contributor to the tubular lesions as observed in cases of true renal gout.

As exemplified here, definitive diagnosis with even the ultra-sensitive PCR is challenging with

infectious bronchitis virus, the most likely cause of disease in this case. This virus is unique

among coronaviruses in that it replicates, mutates and recombines rapidly resulting in the

creation of an extensive number of serotypes. These pose a challenge to poultry producers and

veterinarians, as vaccines do not provide cross-protection for different serotypes, necessitating

the need to develop specific vaccines to the identified serotype associated with an outbreak. Even

the vaccines themselves have been associated with the emergence of new strains capable of

causing disease. The most significant protein for virus detection is the club-shaped glycoprotein

known as spike. Spike mediates cell attachment, fusion and target specificity. It is composed of

two subunits: S1, which makes up the outer portion; and S2, which anchors it to the viral

envelope. The S1 protein is the common target for RT-PCR and can be used to predict levels of

cross-protection between different serotypes of IBV, thus making it the focus of research and

vaccine development for this enduring disease.(7)

References:

1. Chen BY, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of renal lesions due to infectious bronchitis virus in chicks. Avian Pathology. 1996;25(2):269-283.

2. Chen BY, Itakura C. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of renal lesions due to avian infectious bronchitis virus in chicks uninoculated and previously inoculated with highly virulent infectious bursal disease virus. Avian pathology. 1997;26(3):607-624.

3. De Wit JJ. Detection of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian pathology. 2000;29(2):71-93.

4. Fletcher OJ, Abdul-Aziz T, Barnes HJ. Urinary system. In: Fletcher OJ, ed. Avian Histopathology. 3rd ed. Madison, WI: American Association of Avian Pathologists; 2008:241-242.

5. IgnjatoviÄ J, Sapats S. Avian infectious bronchitis virus. Revue scientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics). 2000;19(2):493-508.

6. Imada T, Yamaguchi S, Mase M, Tsukamoto K, Kubo M, Morooka A. Avian nephritis virus (ANV) as a new member of the family Astroviridae and construction of infectious ANV cDNA. Journal of Virology. 2000;74(18):8487-8493.

7. Jackwood MW. Review of infectious bronchitis virus around the world. Avian Diseases. 2012;56:634-641.

8. Narita M, Ohta K, Kawamura H, Shirai J, Nakamura K, Abe F. Pathogenesis of renal dysfunction in chicks experimentally induced by avian nephritis virus. Avian Pathology. 1990;19(3):571-582.

9. Shirai, J, Nakamura K, Narita M, Furuta K, Kawamura H. Avian nephritis virus infection of chicks: Virology, pathology, and serology. Avian Diseases 1989;34(3):558-565.

10. Todd D, Trudgett J, McNeilly F, McBride N, Donnelly B, Smyth VJ, et al. Development and application of an RT-PCR test for detecting avian nephritis virus. Avian Pathology. 2010;39(3):207-213.