Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 23

22 April, 2020

CASE I: 69887 (JPC 4117530).

Signalment: Neutered male Domestic Short Hair cat of unknown age, Felis catus

History: The animal was a rescue shelter cat current on all vaccinations. The animal was presented with dyspnea, hemoptysis and subsequent cardiac arrest.

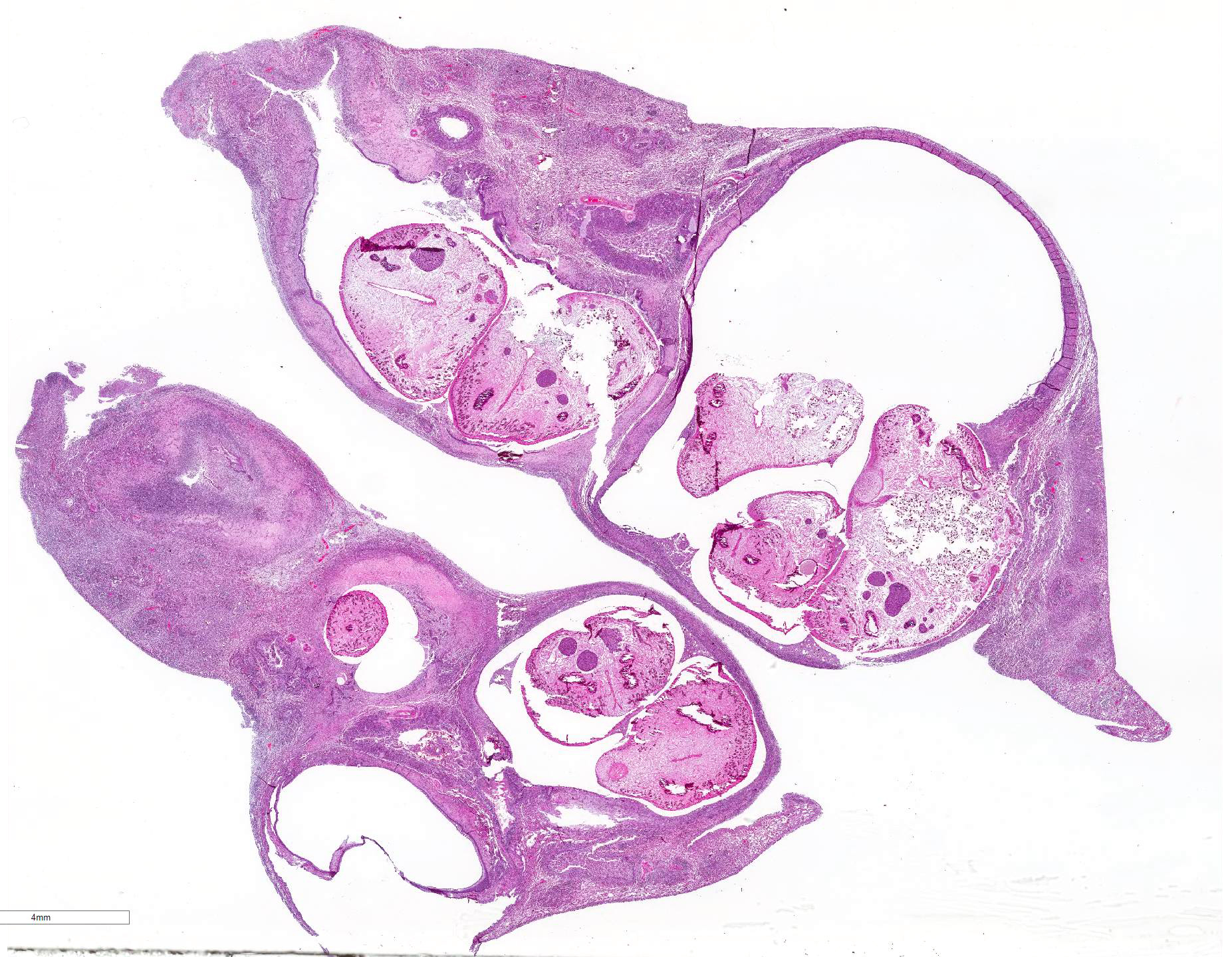

Gross Pathology: The most notable postmortem findings were restricted to the lungs, which were uncollapsed, moist, firm, meaty and diffusely mottled dark red to pink with multifocal to coalescing 2-4mm white/tan raised round nodules. Impression smear of these nodules showed numerous degenerate neutrophils and macrophages. There were also multifocal, dome shaped, raised, 1-2 cm nodules with central cavitations containing few ovoid, reddish-brown ~5 x 10 mm adult trematodes.

Laboratory results: NA.

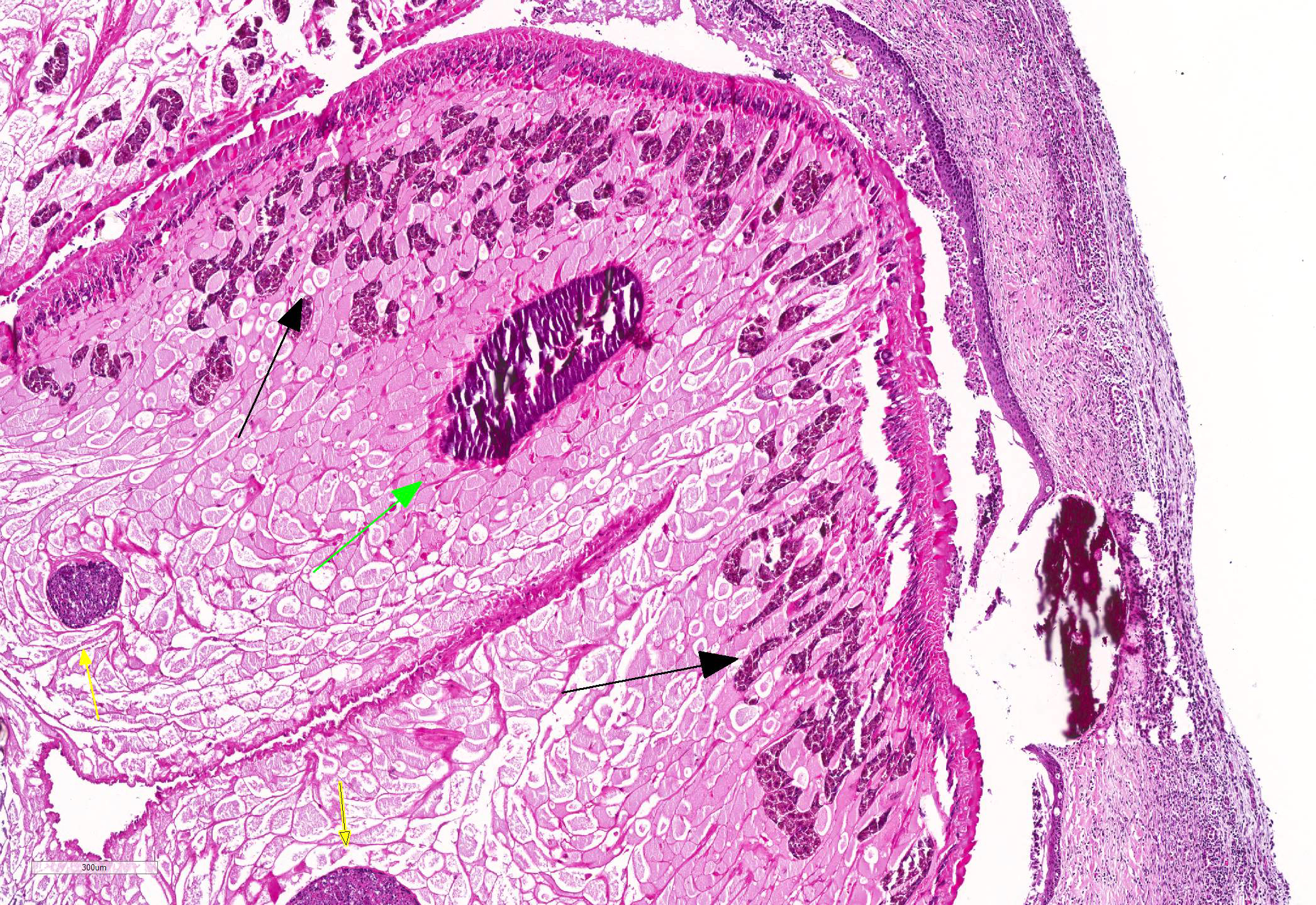

Microscopic Description: Lung: Pyogranulomatous inflammation effaces and replaces up to 40% of the lung parenchyma and occludes bronchi and bronchioles. This inflammation is composed of numerous degenerate and viable neutrophils and macrophages with fewer multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Associated with inflammation, there are multiple adult trematodes, parasitic eggs and multifocal bacterial colonies in the alveolar, bronchiolar and bronchial lumena. Adult trematodes are ~ 6mm X 4mm with a 40um thick spiny tegument and a spongy parenchyma that contains numerous subtegumental vitellaria with eosinophilic globular yolk material, centrally located uterus with numerous egg, few testis containing sperms, and intestinal caeca. The parasite eggs in the adult trematode and airways are 50um X 120um and embryonated with curved 110um X 30um larva, and have 1-3um thick, gold-brown, operculate, ansiotrophic shell. Bacterial colonies are composed of numerous 1-2um cocci enmeshed in a brightly eosinophilic protein matrix (Splendore-Hoeppli material). Bronchi and bronchioles are partially filled with sloughed epithelial cells and low numbers of macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells and surround by moderate numbers of the same inflammatory cells, hyperplastic peribronchial mucous glands and mild fibrosis. Many bronchi containing adult trematodes are lined by lined by squamous epithelium (squamous metaplasia). Less affected areas have pigment-laden macrophages, eosinophilic proteinaceous material (edema) and hemorrhage. Multifocally, small and medium caliber blood vessels have tunica media and intima thickened by hypertrophic and vacuolated smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, respectively, and multifocally surrounded by paler connective tissue separated by clear space (edema). There is multifocal bronchiolar and alveolar smooth muscle hypertrophy. The pleura is thickened up to 50um by inflammatory infiltrate and increased fibrosis and lined by plump and cuboidal mesothelial cells (reactive).

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung, pneumonia pyogranulomatous and lymphoplasmacytic, multifocal to coalescing, chronic active, severe with pleuritis and trematode adults and eggs and bacterial cocci

Etiologic diagnosis: Pulmonary Paragonimiasis

Cause: Paragonimus kellicotti

Contributor Comment: Pulmonary paragonimiasis is a parasitic disease caused by trematodes of the genus Paragonimus and the family Troglotrematidae. It is an important food-borne zoonotic disease affecting crayfish eating mammals and human worldwide, but it is most common in China, southeast Asia, and North America (1). At least 28 species of Paragonimus have been discovered (1). P. westermani (China and southeast Asia) and P. kellicotti (North America) are the two most common species (2).

Adult trematodes are usually found in the lung of definitive hosts (human and wild and domestic animals, including dogs and cats) (1). Trematodes are also rarely found in other viscera and brain (extrapulmonary paragonimosis)(1). The first and second intermediate hosts are small aquatic snails (cercariae stage) and crayfish or crabs (metacercariae stage), respectively (2, 4). Once the second intermediate hosts are ingested by definitive hosts such as dogs and cats, the metacercariae are liberated into the intestine and subsequently migrate across the peritoneal and pleural cavities into the lung where they mature, form cysts and cause pyogranulomatous inflammation and fibrosis (2, 4). The mature adults lay eggs into the bronchioles or bronchi and the eggs are coughed up the tracheobronchial tree, swallowed and passed in feces or excreted in the sputum (2, 4). In the external environment, the eggs hatch and release ciliated miracidia, which infect the first intermediate hosts such as aquatic snails (2).

Clinical signs include intermittent cough, weakness and lethargy (4). Pathologic lesions are principally due to the presence and migration of adult trematodes and eggs and metabolites produced by trematodes (1). Common pulmonary lesions include pyogranulomatous pneumonia, catarrhal and eosinophilic bronchitis and pleuritis (4). In addition, pneumothorax also can happen rarely due to rupture of parasitic cysts (4). Ectopic extrapulmonary paragonimosis occur more often than in other mammalian species (1). Common sites extrapulmonary Paragonimosis are the brain, spinal cord, abdominal cavity and subcutis (1).

Contributing Institution:

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Department of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/mcp

JPC Diagnosis: Adult trematodes, encysted, multiple, with diffuse atelectasis and multifocal pyogranulomatous bronch pneumonia with trematode eggs.

JPC Comment: Paragonimiasis

is an uncommon acquired infection of crustacean-eating animals. Of the

approximately 30 named species of Paragonimus, ten are considered

pathogenic, but the overwhelming number of cases occur, as mentioned above, as

a result of P. westermani infection in Asia, and P. kellicotti in

the United States.

P. rudis was the first lung fluke to be described by Natere in 1828, P.

westermani was first described by Conrad Kerbert in 1878 in a Bengal tiger

at the Amsterdam Zoo and named for the zoo?s curator, C.F Westerman. The next

year, B.S. Ringer identified the first case of human paragonimiasis in the

lung, and the following year, Patrick Manson and Erwin von Baetz independently

diagnosed cases by viewing fluke eggs in human sputum for the first time. The

first case of P. kellicotti in the U.S. was identified in a dog in Ohio

by Kellicott in 1894, and in a cat by Ward, and the first human case of P.

kellicotti was identified by Abend in 1910.

Human paragonimiasis is far more common in Asia, where it is considered

endeminc in some areas of China and Southeast Asia in humans who eat raw,

undercooked, or alcohol-pickled freshwater crayfish. In the U.S., cases of

non-native paragonimiasis (P. westermani infection from eating imported

Asian crabs) still outweigh cases of native paragonimiasis (P. kellicotti

infection from consuming raw or undercooked crayfish). Published risk factors

for cases of native paragonimiasis include young males (males outweigh females

15:1), alcohol consumption, and paddling, boating, or camping along the upper

Mississippi river valley, with a particular concentration in the state of

Missouri. Many cases of nonnative paragonimiasis arise as a result of eating

poorly cooked imported crabs, often in sushi restaurants. In parts of Asia

where ?drunken crabs? (ethanol-picked crabs) are a delicacy, up to 30% of the

local population have antibodies to P. westermani. A resurgence in

consumption of wild boar meat in Japan has resulted in a number of cases of

infection with P. miyazakii.

The contributor has described the complex life cycle of lung flukes with multiple intermediate hosts. Young pathologists are often intrigued by the very characteristic presence of two hermaphroditic flukes in each cyst (as illustrated in this case). Paragonimus flukes are indeed hermaphroditic, with presence of both testicular and ovarian tissue within an individual. While under certain circumstances they can self-fertilized, cross-fertilization is generally the rule (hence the presence of two flukes) and the cysts are known as ?mating cysts?.)

In humans, the prepatent period for both nonnative and native paragonimasis is 2 to 16 weeks with an average of 10 weeks. The initial clinical signs occur days following ingestion with abdominal cramps, diarrhea and fever (likely the period of migration of metacercaria out of the intestine.). After 2-16 weeks, a constellation of clinical signs occur, including fever, ?rusty? hemoptysis (due to the presence of red blood cells from rusty mating cysts.), and peripheral eosinophilia. Respiratory infections are the rule, although aberrant migration may result in cutaneous infections (trematoda larval migrans) or cerebral infections. Complications of respiratory infections in humans include pneumothorax, constrictive pleuritis and pleural effusions. Following diagnosis, treatment with praziquantel generally effects a cure.

References:

1. Madarame H, Suzuki H, Saitoh Y, Tachibana M, Habe S, Uchida A and Sugiyama H. Ectopic (subcutaneous) Paragonimus miyazakii infection in a dog. Vet Pathol. 2009 Sep;46(5):945-8.

2. Blair D. (2014) Paragonimiasis. In: Toledo R., Fried B. (eds) Digenetic Trematodes. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 766. Springer, New York, NY.

3. Gardiner CH, Poyton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissue. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1990:46-48.

4. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory System. In: Maxie ME, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2, Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:591.