CASE 3: P17-1884 (4117377-00)

Signalment:

1-year-old male neutered DSH cat (Felis catus)

History:

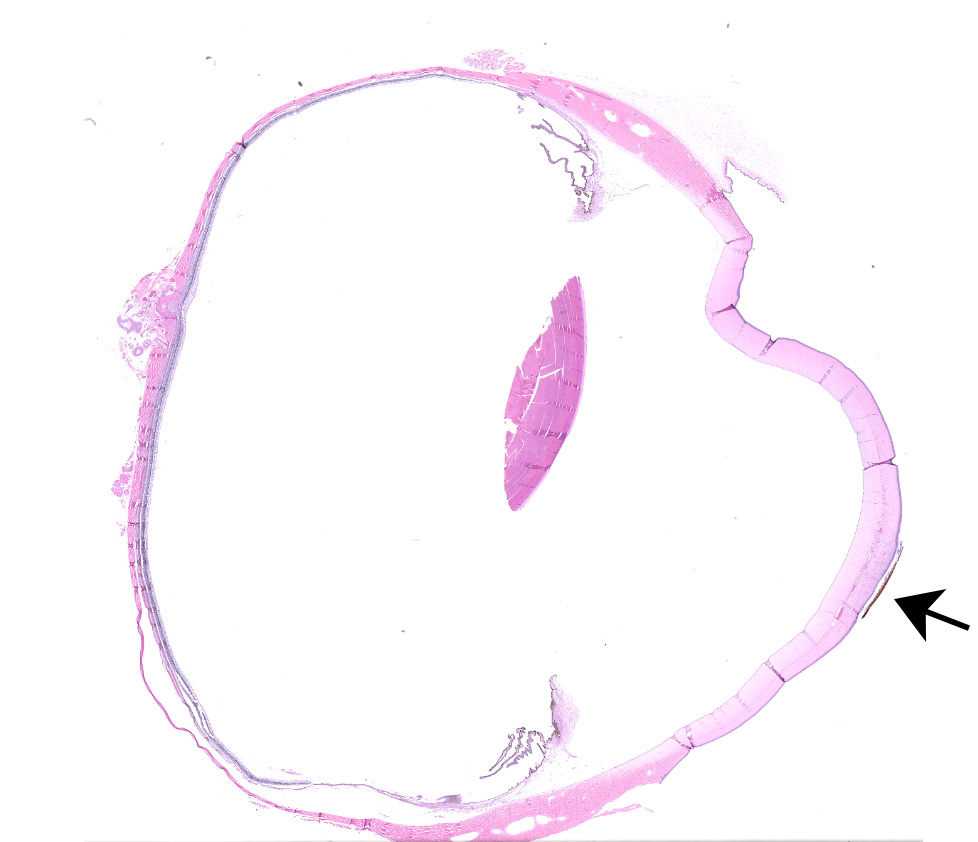

A black spot was noted on the eye by the owner and the eye was enucleated.

Gross Pathology:

The cornea has a 0.5 mm diameter black spot on the surface.

Laboratory results:

None.

Microscopic description:

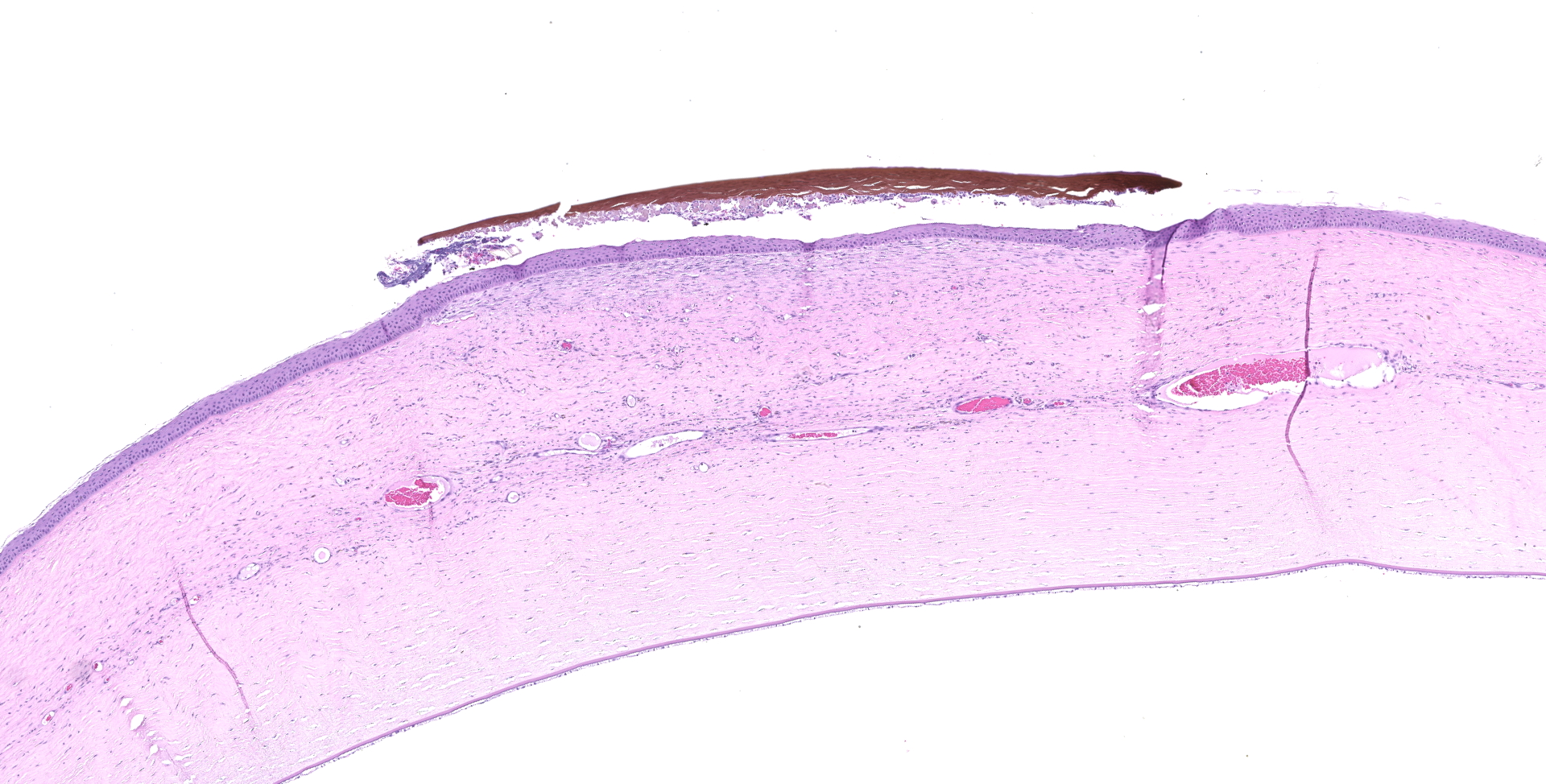

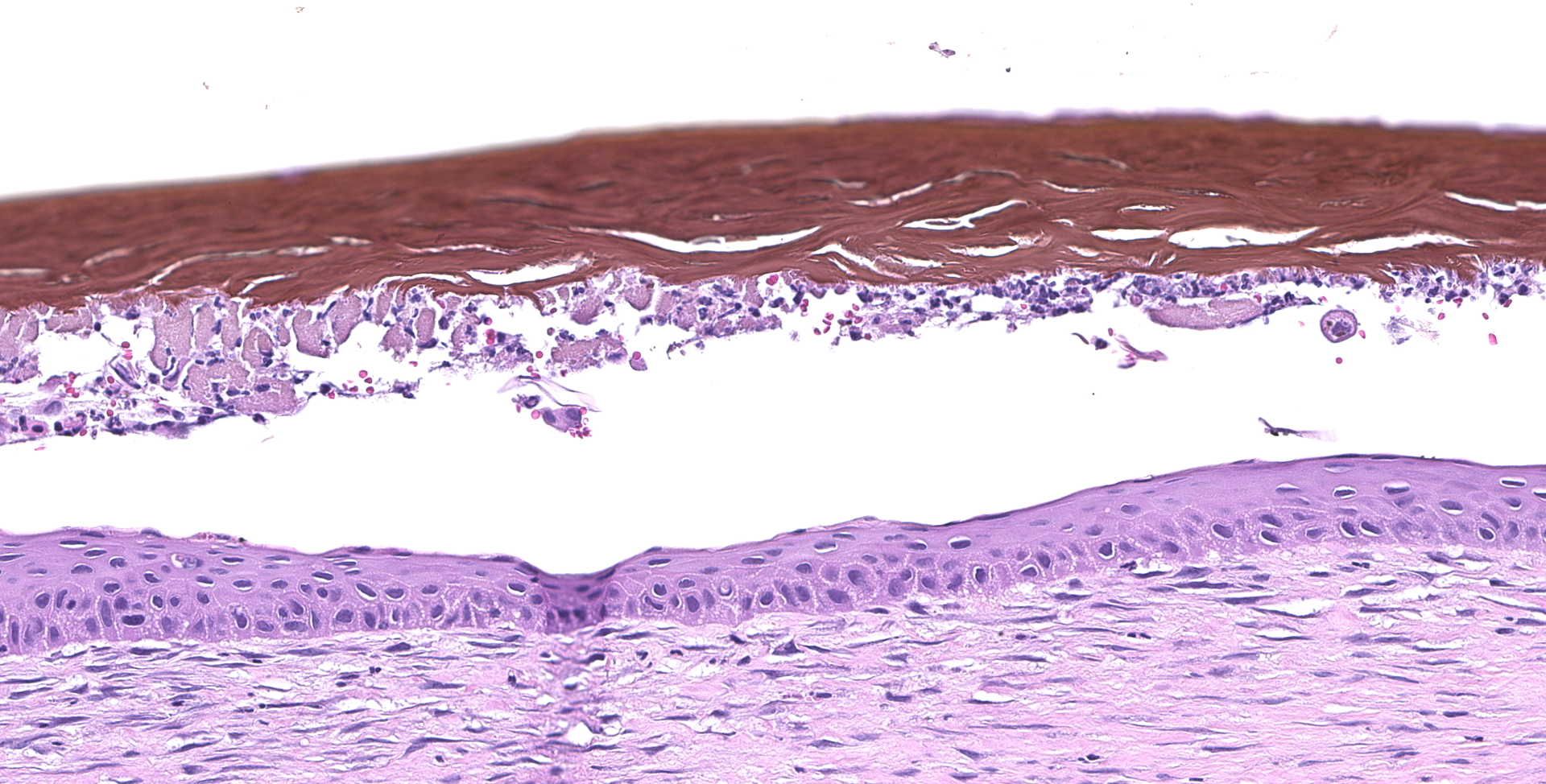

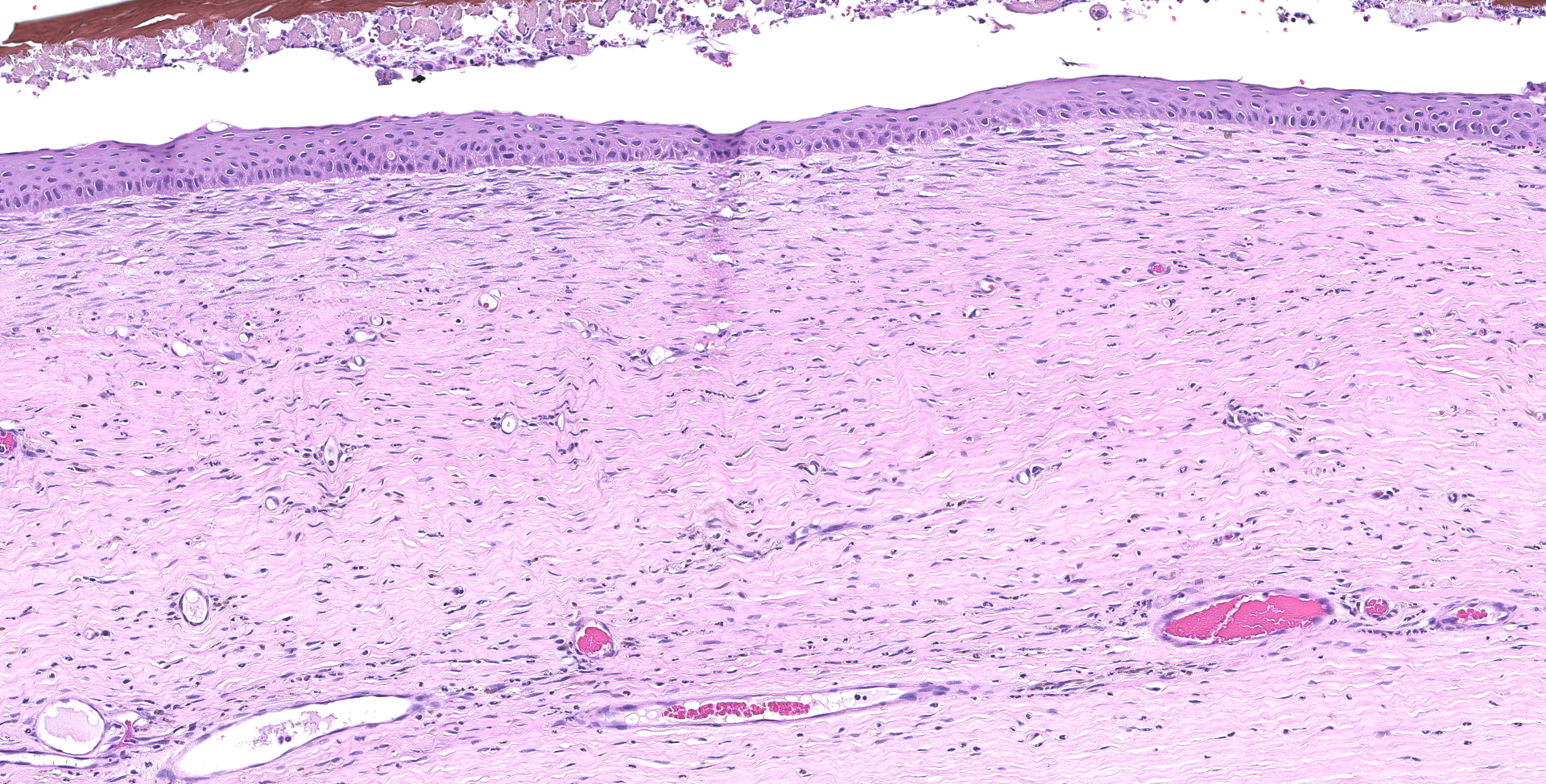

Adherent to the ulcerated cornea is a plaque of acellular brown-staining, fibrillary material. The corneal ulcer has a bed of granulation tissue extending half the thickness of the stroma. Neutrophils cover the ulcerated surface and extend through the granulation tissue. A few neutrophils are in the surface plaque. The corneal epithelium at the margin of the ulcer has hyperplasia.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Corneal sequestrum

Ulcerative, suppurative keratitis

Contributor's comment:

A corneal sequestrum is an aggregate of degenerate corneal stromal collagen which becomes pigmented with amber to black pigment. It has also been called partial corneal mummification or corneal nigrum.3,5-7

The cause of corneal sequestrum is not known. It may be a response to corneal irritation or be associated with ocular trauma.3,5-7 The source of the pigment also is not known. One investigator found melanin in the sequestrum2, but others have not substantiated this.

Corneal sequestrum occurs more commonly in brachycephalic breeds, Siamese, and domestic short hair cats.5-7 The condition is usually unilateral but can be bilateral in the predisposed breeds.3

The ulcerative keratitis is a response to the collagen degeneration of the sequestrum. The sequestrum develops in the stroma but is gradually extruded through the epithelium and comes to lie on the surface of the cornea.

Contributing Institution:

College of Veterinary Medicine

Virginia Tech

Blacksburg, VA 24061

www.vetmed.vt.edu

JPC diagnosis:

Cornea: Necrosis, coagulative, focally extensive, with pigmentation and vascularization.

JPC comment:

There is some slide variation between participants, with some sections containing colonies of cocci adherent to the sequestrum. The moderator also briefly discussed picrosirius red, a histochemical stain that allows for the differentiation between healthy and degenerative collagen fibers. Unfortunately, that histochemical stain was not available for this case.

The pathogenesis of feline corneal sequestrum is incompletely understood. However, as the contributor stated, brachycephalic breeds, specifically Persian and Himalayan cats, are more often affected. While early cases may lack the typical discoloration, lesions are characterized by a discrete focus of non-inflammatory necrosis of corneal stromal keratocytes. The stroma affected usually exhibits pallor, hyalinization, and orange discoloration. Sequestra may be accompanied by a concurrent ulceration of the overlying corneal epithelium, or there may be evidence of prior ulceration.9

Suggested predisposing factors leading to corneal sequestra include corneal trauma, topical corticosteroid use, primary corneal dystrophy, altered corneal stromal metabolism, chronic corneal ulcers or keratitis, often by feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1) or mechanical irritation from entropion or trichiasis.1,8 During routine histologic analysis, apoptotic keratinocytes have been noted, possibly suggesting a role for apoptosis in the development of these lesions.8

On transmission electron microscopy (TEM), sequestra contained variable amounts of amorphous, electron-dense substance, continuous with intact basement membrane to the periphery. Remnants of necrotic keratocytes were observed between loosely packed collagen bundles subjacent to ulceration. Occasionally, keratocytes were characterized by clumped and marginated chromatin, with shrunken cytoplasm, changes consistent with apoptosis.1

Studies comparing the association of FHV-1 with corneal sequestrum in Persian and Himalayan cats did not find a correlation, with the control group having much higher rates of PCR positive results for FHV-1.8 Additionally, there does not appear to be an association between qualitative tear film abnormalities, abnormal goblet cell numbers, Chlamydia psittaci, or Mycoplasma felis.4

References:

- Cullen CL, Wadowska DW, Singh A, Melekhovets Y. Ultrastructural findings in feline corneal sequestra. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2005;8(5):295-303.

- Featherstone HG, Franklin VJ, Sansom J. Feline corneal sequestrum: laboratory analysis of ocular samples from 12 cats. Vet Ophthal. 2004;7:229-238.

- Featherstone HG, Sansom J. Feline corneal sequestra:a review of 64 cases (80 eyes) from 1993-2000. Vet Ophthal. 2004;7:213-227.

- Grahn BH, Sisler S, Storey E. Qualitative tear film and conjunctival goblem cell assessment of cats with corneal sequestra. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2005;8(3):167-170.

- Laguna F, Leiva M, Costa D, Lacerda R, Gimenez TP. Corneal grafting for the treatment of corneal sequestrum. Vet Ophthal. 2015;18:291-296.

- Oria AP, Soares AMB, Laus JL, Neto FD. Feline corneal sequestration. Ciencia Rural. 2001;31:553-556.

- Sandmeyer LS, Breaux CB, Grahn BH. Diagnostic Ophthalmology. Canadian Vet J;51:1295-1296.

- Stiles J. Feline Ophthalmology. In: Gelatt KN, Gilger BC, Kern TJ, eds. Veterinary Ophthalmology, 5th Ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley and Sons. 2013;1493-1496.

- Wilcock BP. Eye. In: eds. Maxie MG, Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016; 434.