Signalment:

5-month-old male Great Dane, canine (

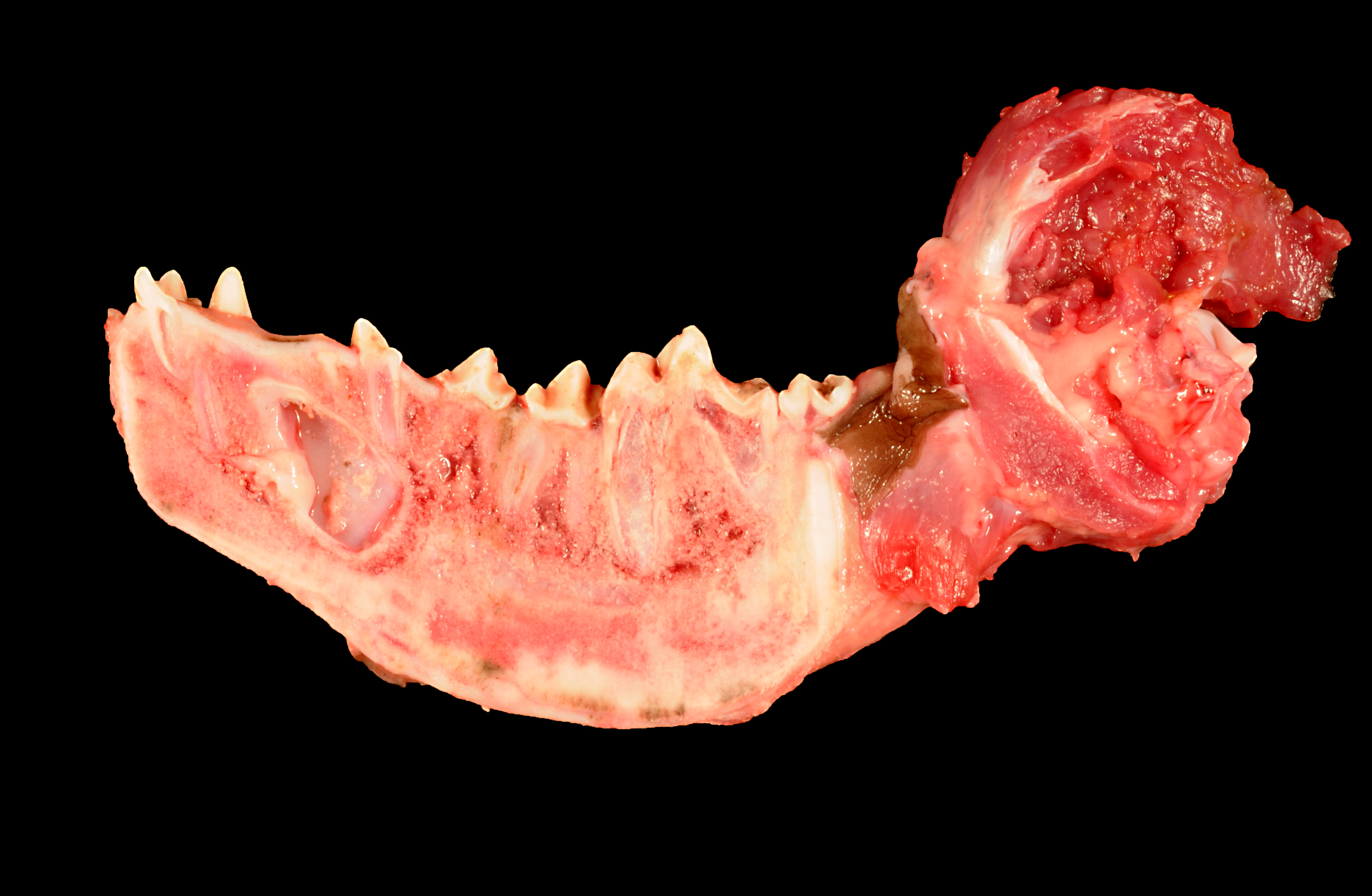

Canis lupus familiars).A 5-month-old male Great Dane was euthanized for multiple

congenital heart defects. Necropsy confirmed a clinical suspicion of a ventricular septal defect,

pulmonic stenosis, tricuspid dysplasia and severe right ventricular dilation. In addition, both

mandibles were uniformly expanded by marked, diffuse bony proliferation that preserved

mandibular anatomy. Multiple axial and appendicular bones including the radius, ulna, humerus

and femur were sectioned and were normal.

Histopathologic Description:

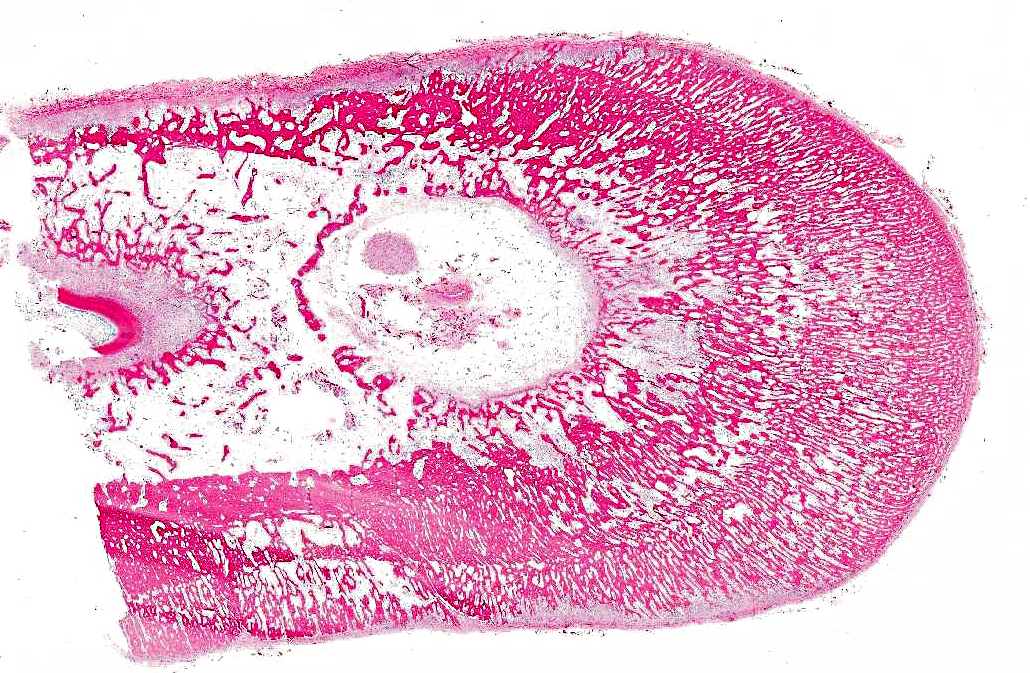

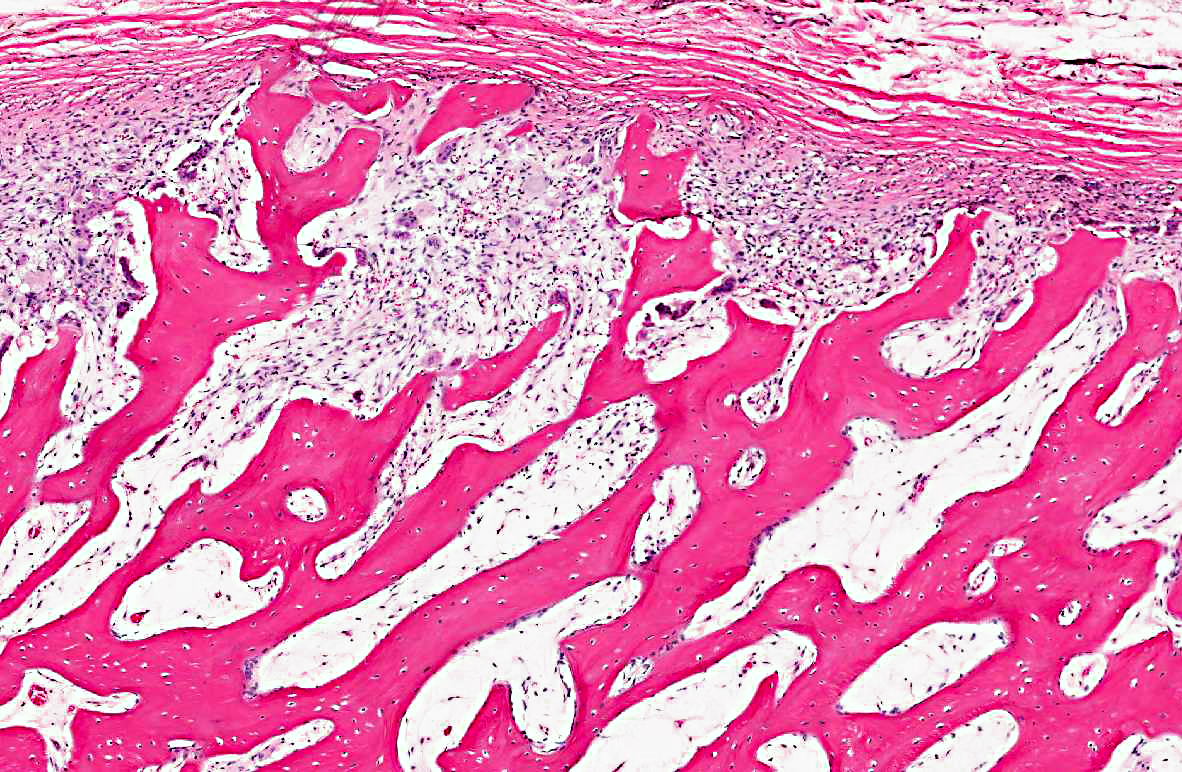

Bone, mandible: Diffusely filling and expanding the mandible by

4 to 5 times the normal size, is a well-organized subperiosteal proliferation of bone that extends

from the periosteum into the medullary cavity and to the lamina dura of teeth. The cortex is not

evident. This bone proliferation is composed of approximately 90% woven bone and 10%

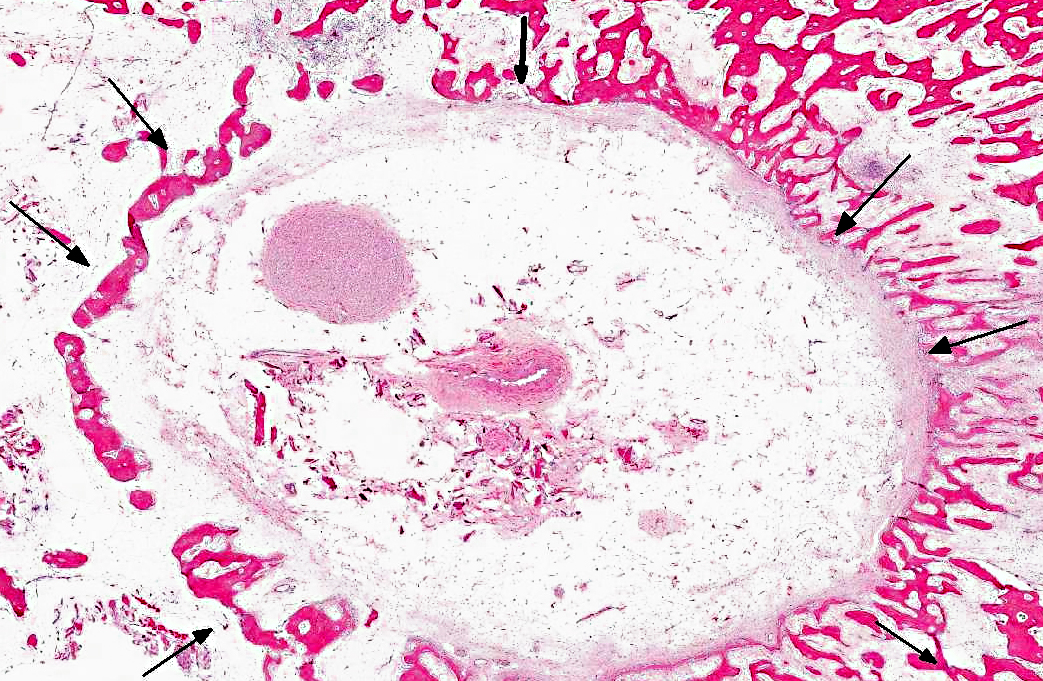

lamellar bone, with a concentration of lamellar bone at the periphery. Haversian canals can be

seen on cross sections of the trabeculae. Trabeculae are frequently lined by a single layer of

well-differentiated osteoblasts that are occasionally interrupted by osteoclasts within Howships

lacunae. Trabeculae are densely packed with small areas separated by moderate amounts of

loose fibrous connective tissue mixed with many plump fibroblasts that are punctuated by rare

aggregates of degenerative neutrophils and eosinophils, mixed with small amounts of necrotic

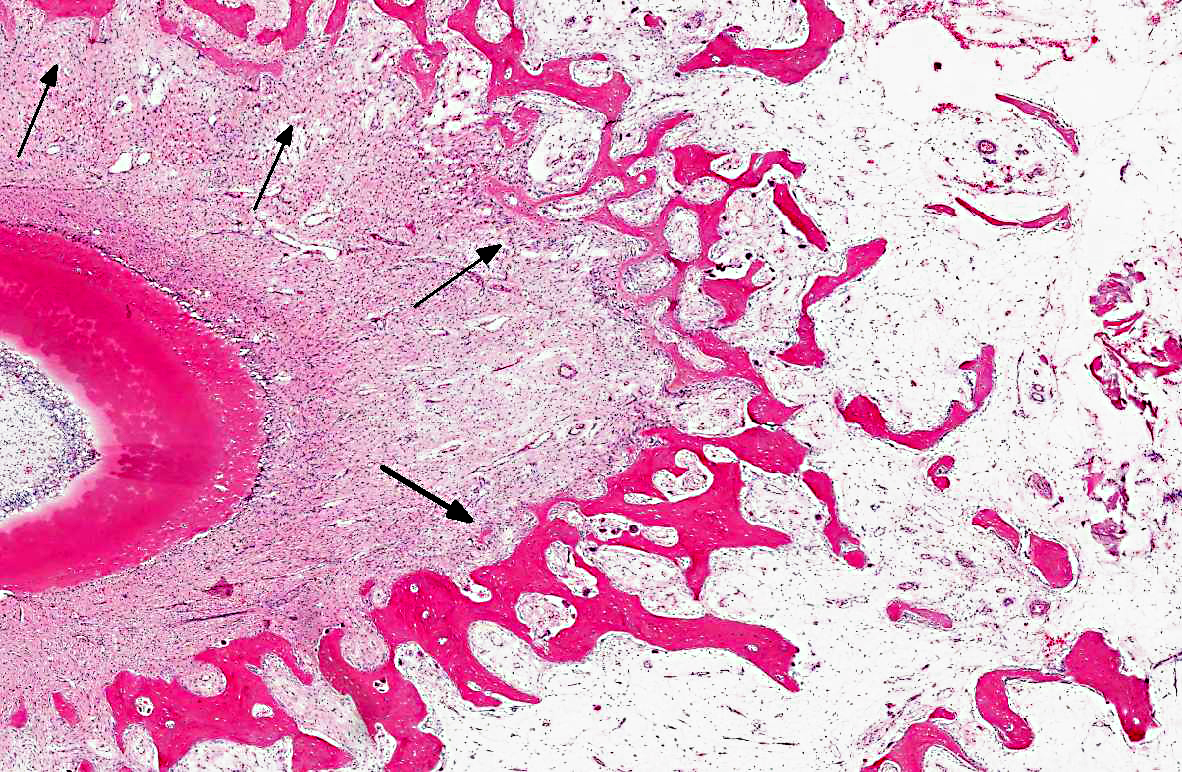

cellular debris. There is an absence of hematopoietic elements. Multifocally, the cambium is

irregularly expanded up to 3 times normal by dense granulation tissue that merges with the bony

trabeculae. There is a moderate increase in osteoclastic activity along this junction. Centrally, a

single tooth is present and surrounded by periodontal ligament that merges with dentin, with an

absence of cementum.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Bone, mandible: Hyperostosis, diffuse, marked.

Condition:

Craniomandibular osteopathy

Contributor Comment:

This is a classic case of craniomandibular osteopathy, with bony

expansion of the jaw characterized by filling of the medullary spaces with woven bone.

Craniomandibular osteopathy (CMO) or lion jaw is a nonneoplastic, proliferative bony disease

of the dog affecting primarily the mandible, tympanic bullae, and occasionally other bones of the

head, and rarely long bones of unknown etiology.(1) The disease predominates in Scottish terriers,

West Highland White Terriers, and Cairn Terriers; however, other dog breeds such as boxers,

Shetland sheepdog, Great Danes, Doberman pinschers and Labrador retrievers have also been

reported in the literature.(1,2,4,5,8,9) The disease is seldom recognized until signs of discomfort due

to chewing and eating are observed. This usually occurs when the dogs are 4 to 7 months old. It

is likely that this dog was euthanized before clinical signs developed. In addition, the peripheral

replacement of woven bone by lamellar bone in this case is suggestive of resolution of the

disease. The pathogenesis of CMO is unknown but is likely multifactorial. Some cases resolve

spontaneously and in others the pain is so great that owners request euthanasia. This animal has

multifocal areas of subperiosteal bone resorption with granulation tissue. This is interpreted to

be secondary to trauma or inflammation, rather than as part of the primary disease process.

Long-bone involvement has been reported mainly in West Highland White Terriers. In a 1995

retrospective study of 10 terriers, 2 terriers had long-bone involvement.(7) Our dog was a Great

Dane and did not have long bone involvement.

JPC Diagnosis:

Mandible: Subperiosteal new bone growth, diffuse, marked, with medullary fibrosis

Conference Comment:

CMO is characterized by intermittent and concurrent bone resorption

and production involving the endosteum, periosteum, and trabecular bone of the skull (most

often the mandible).(6) As the contributor states, the pathogenesis of CMO is unknown. The

occurrence of this condition in multiple breeds may suggest more than one cause.(6) In West

Highland White and Scottish Terriers there is some evidence that CMO is an autosomal recessive

inherited trait. Alternatively, the presence of inflammation in many cases has raised the

suspicion of an infectious etiology, although none has yet been identified. It is also possible that

both an inherited predisposition followed by an additional factor or agent is necessary to initiate

disease.(6)

Conference participants compared and contrasted CMO and hypertrophic osteopathy (HOD),

another syndrome that is characterized by periosteal new bone formation. HOD is often

associated with thoracic cavity chronic inflammation or neoplasia, as well as with botryoid

rhabdomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder in dogs and ovarian tumors in horses.(6) In contrast to

the distribution of CMO, which is usually confined to the bones of the skull, the periosteal

hyperostotic lesions associated with HOD generally occur along the diaphyses and metaphyses

of certain bones (predominantly the radius, ulna, tibia, metacarpals, metatarsals); however, HOD

bony proliferation can occasionally occur in the mandible as well. Like CMO, the pathogenesis

of HOD is poorly understood, and although several mechanisms have been proposed to explain

the increased blood flow to the limbs that appears to consistently occur early in HOD, the exact

cause remains unknown.(6)

References:

1. Burk RL, Broadhurst JJ. Craniomandibular osteopathy in a Great Dane.Â

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1976;169(6):635-6.

2. LaFond E, Breur GJ, Austin CC. Breed susceptibility for developmental orthopedic diseases in dogs.Â

J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2002;38:467477.

3. WH Riser, CD Newton. International Veterinary Information Service, www.ivis.org. Document No. B0055.0685.

4. Schulz S. A case of craniomandibular osteopathy in a Boxer.Â

J. smd Anim. Pract. 1978;19:749-757.

5. Taylor SM, Remedios A, Myers S. Craniomandibular osteopathy in a Shetland sheepdog.Â

Can Vet J. 36(7): 437439, 1995.

6. Thompson K. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG, ed.

Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animal. Vol. II, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:106-108.

7. Watson ADJ, Adams WM, Thomas CB. Cranomandibular osteopathy in dogs.Â

Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian. 1995:17:911.

8. Watson ADJ, Huxtable CRR, Farrow BRH. Craniomandibular osteopathy in Doberman Pinschers.Â

J. small Anim. Pract. 1975;16:11-19.

9. Watkins JD, Bradley RR. Craniomandibular osteopathy in a Labrador puppy.Â

Vet Rec. 1966;79:262.