Signalment:

Gross Description:

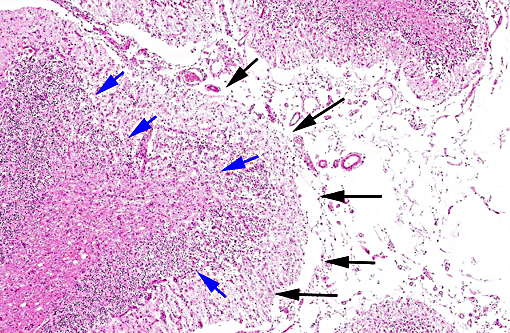

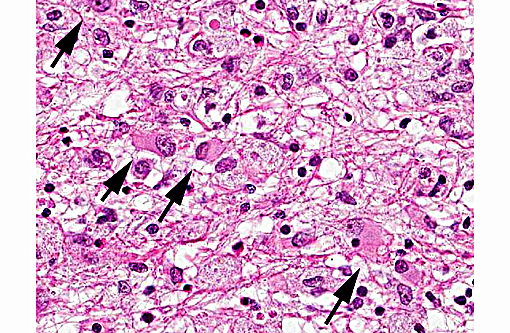

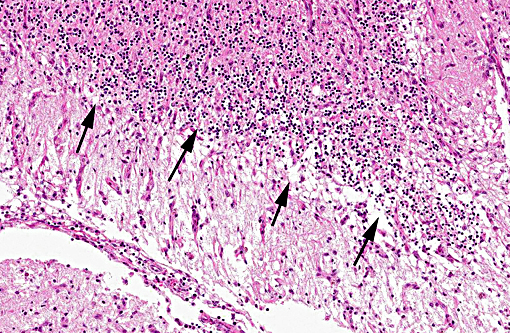

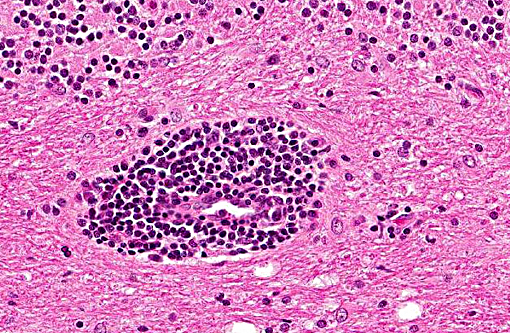

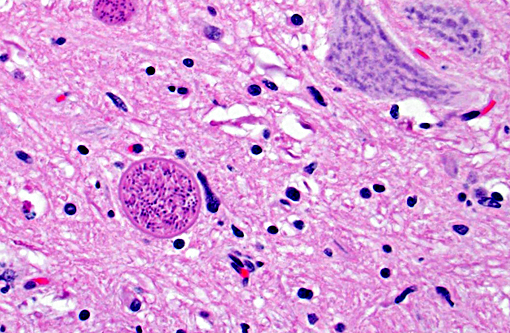

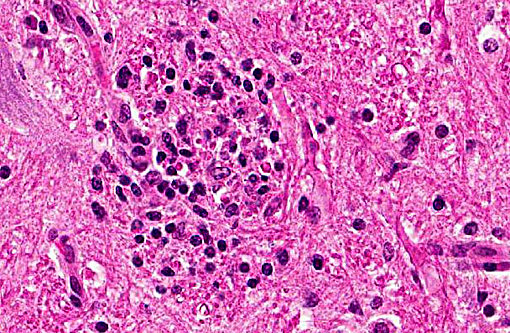

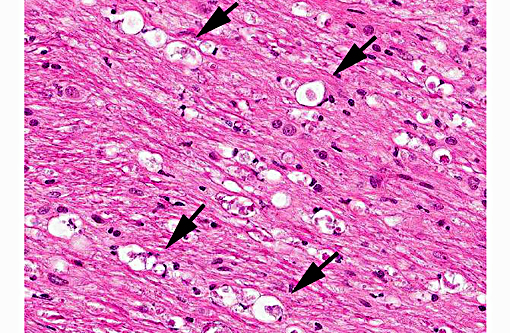

Histopathologic Description:

In tissues not included for conference material, also contain similar lesions and protozoal tissue cysts. These lesions were noted in the cerebrum, midbrain, thalamus, and spinal cord with mild infiltration of the spinal nerve roots.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Infection in adult dogs can result in polymyositis, polysystemic infection, or multifocal central nervous system involvement.(8,10) Several reports describe necrotizing cerebellitis and cerebellar atrophy as a significant lesion associated with Neospora encephalitis in adult dogs.(3,11,12) This particular case is unique in that it is significant the necrotizing cerebellar lesions were found in a puppy. Transmission of N. caninum in dogs may occur both vertically and horizontally. Vertical transmission is well recognized in the dog with data suggesting that transmission from the dam to puppies occurs transplacentally, during the terminal stages of gestation, or postnatally via milk.(9) Horizontal transmission also occurs in the dog through ingestion of infected tissues.(9) Further communications with the breeder revealed that the dam of this puppy, as well as 10 other dogs from the same kennel, was fed a diet of raw beef and deer. Additional serological testing revealed that dam, as well as 4 other dogs, tested positive for Neospora caninum. The diet of raw tissues were the likely source of infection in the dam with subsequent horizontal transmission this puppy. Given that most puppies do not develop clinical signs until over 4 weeks of age,(8) it is difficult to determine if transplacental or postnatal infection occurred in this case.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Differential diagnosis considered for this case included Toxoplasma gondii as well as Sarcocystis spp. Many features of toxoplasmosis and neosporosis are similar including the presence of the proliferative tachyzoite and tissue cyst phases. However, N. caninum does not develop in a parasitophorus vacuole and has a thicker cyst wall than T. gondii. The differences cannot be reliably differentiated by light microscopy, and require the use of electron microscopy or immunohistochemistry in many cases.(14) Ultrastructural differences include greater number of micronemes and rhoptries with N. caninum, in addition to a thicker cyst wall.(12) N. caninum is more commonly reported in the CNS where the tissue cysts are most commonly found; although T. gondii has a CNS form causing similar histologic changes. N. caninum seems to have an affinity for cells of the monocyte macrophage system, although many cell types can be infected, and it likely spreads to the CNS via leukocyte trafficking.(14) Toxoplasmosis seems to affect a wider variety of mammalian species

Although very uncommon, both Sarcocystis canis and Sarcocystis neurona have been documented to cause CNS disease in dogs,(12) In one documented case of S. neurona the affected dog was receiving immunosuppressive therapy and developed widespread encephalitis, predominantly in the grey matter, with brainstem, cerebellum and cerebrum being involved. The lesions also consisted of intense areas of inflammation, which was most pronounced in the cerebellum. (4) The dividing schizonts of S. neurona form distinct rosettes of merozoites, arranged around a prominent residual body and their schizonts differ from other protozoa in that the merozoites lack rhoptries.(14) Encephalo-myelitis due to S. neurona infection has also been described in cats, which along with many other mammals including harbor seals and nonhuman primates, can serve as intermediate hosts for S. neurona.(12)

References:

1. Barber JS, Trees AJ. Clinical aspects of 27 cases of neosporosis in dogs. Vet Rec. 1996; 139(18): 439-443.

2. Bjerkas I, Mohn SF, Presthus J. Unidentified cyst-forming sporozoon causing encephal-omyelitis and myositis in dogs. Z Parasitenkd. 1984; 70(2): 271-274.

3. Cantile C, Arispici M. Necrotizing cerebellitis due to Neospora caninum infection in an old dog. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2002; 49(1):47-50.

4. Cooley AJ, Barr B, Rejmanek D. Sarcystis neurona encephalitis in a dog. Vet Pathol. 2007;44:956-961.

5. Dubey JP. Recent advances in Neospora and neosporosis. Vet Parasitol. 1999; 84(3-4): 349-367.

6. Dubey JP: Review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis in animals. Korean J Parasitol. 2003; 41(1): 1-16.

7. Dubey JP, Carpenter JL, Speer CA, et al.: Newly recognized fatal protozoan disease of dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1988; 192(9): 1269-1285.

8. Dubey JP, Lindsay DS: A review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis. Vet Parasitol. 1996; 67(1-2): 1-59.

9. Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM: Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007; 20(2): 323-367.

10. Gaitero L, Anor S, Montoliu P, et al. Detection of Neospora caninum tachyzoites in canine cerebrospinal fluid. J Vet Intern Med. 2006; 20(2): 410-414.

11. Garosi L, Dawson A, Couturier J, et al. Necrotizing cerebellitis and cerebellar atrophy caused by Neospora caninum infection: magnetic resonance imaging and clinicopathologic findings in seven dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2010; 24(3): 571-578.

12. Greene CE. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:825, 836-838.

13. Lorenzo V, Pumarola M, Siso S. Neosporosis with cerebellar involvement in an adult dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2002; 43(2): 76-79.

14. Zachary JF. Nervous system. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:809, 841.