Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

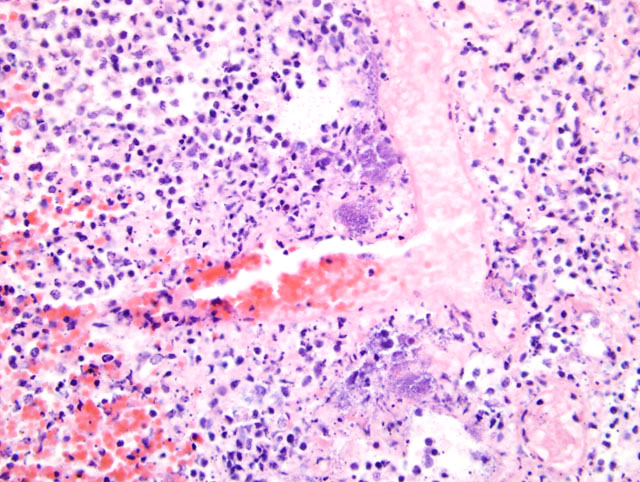

In the tracheobronchial lymph nodes there was lymphocellular necrosis, hemorrhage and medullary hemosiderosis. Widespread, acute centrilobular hepatic necrosis was the only other significant finding.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Hemorrhagic and necrotizing pneumonia caused by necrotoxigenic E. coli has recently been described in dogs1,4. In common with the present case, affected dogs have been young (<1year), the clinical illness is usually less than 24 hours and immunodeficiency or concurrent illness were not identified. In our case, parainfluenza virus and adenovirus testing were not performed and while no inclusion bodies were identified, concomitant infection with these agents cannot be excluded. E. coli of both O4 and O6 serotypes have been reported to cause these lesions, which irrespective of serotype were positive for CNF1.Â

The main differential diagnoses for hemorrhagic pneumonia in dogs are canine influenza and bacterial septicemias including streptococcal septicemia 2,3. Microscopically, canine influenza is characterized by a pneumonia that is more broncho-interstitial and suppurative; with less necrosis 2, but RT-PCR or virus isolation is best performed for definitive exclusion. Samples of lung from this case were negative for canine influenza by RT-PCR.

Little is known about the source and route of infection, means of transmission and pathogenesis of this disease in dogs.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

O antigens (somatic): Determines the serogroup, lipopolysaccharide molecule

H antigens (flagellar): Determines the serotype

K antigens (capsular): Made up of polysaccharides and proteins; may also be used for classification purposes

Fimbrial or pili antigens: Important in adhesion and colonization of epithelium

Extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli have been associated with pyometra, mastitis, otitis, prostatitis, bacteremia, skin diseases, cholecystitis, and pneumonia. Strains producing the cytotoxic necrotizing factor (CNF) are referred to as necrotoxic E. coli.4 These strains produce either CNF1, identified in humans and domestic animals, or CNF2, identified only in ruminants.4,5 The genes that code for CNF-1 and alpha hemolysin are genetically linked and have a tendency to occur with O4 and O6 groups.1,4

The primary fimbrial antigen in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli is the P fimbriae and is encoded by the pap (pilus-associated pyelonephritis) gene.1,4 The papG (fimbrial tip adhesion) and papA (major fimbrial subunit) alleles have also been associated with necrotoxic E. coli.1,4

References:

2. Crawford PC, Dubovi EJ, Castleman WL, Stephenson I, Gibbs EP, Chen L, Smith C, Hill RC, Ferro P, Pompey J, Bright RA, Medina MJ, Johnson CM, Olsen CW, Cox NJ, Klimov AI, Katz JM, Donis RO: Transmission of equine influenza virus to dogs. Science 310:482-485, 2005

3. Garnett NL, Eydelloth RS, Swindle MM, Vonderfecht SL, Strandberg JD, Luzarraga MB: Hemorrhagic streptococcal pneumonia in newly procured research dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 181:1371-1374, 1982

4. Handt LK, Stoffregen DA, Prescott JS, Pouch WJ, Ngai DT, Anderson CA, Gatto NT, DebRoy C, Fairbrother JM, Motzel SL, Klein HJ: Clinical and microbiologic characterization of hemorrhagic pneumonia due to extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in four young dogs. Comp Med 53:663-670, 2003

5. Garnett NL, Eydelloth RS, Swindle MM, Vonderfecht SL, Strandberg JD, Luzarraga MB: Hemorrhagic streptococcal pneumonia in newly procured research dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 181:1371-1374, 1982

6. Songer JG, Post KW: The genera Escherichia and Shigella. In: Veterinary Microbiology - Bacterial and Fungal Agents of Animal Disease, eds. Songer JG, Post KW, pp. 113-119. Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, MO, 2005