Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 7, Case 1

Signalment:

8-year-old, male castrated, 20.3 kilograms crossbreed dog (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

The dog was rescued by a local animal shelter and presented to Ross University Veterinary Clinic for panting. All vitals and hematologic and serum chemical analysis results were within the reference range. Two weeks later, the dog was presented again for evaluation of difficulty breathing, non-productive cough, and inappetence. On physical examination of the most recent consultation, the dog was depressed with a lowered head carriage and showed signs of dyspnea and abdominal breathing. Auscultation revealed muffled heart sounds. The veterinarian discussed the possibility of a late-stage tumor and suggested euthanasia if the condition deteriorated due to quality-of-life concerns. The patient presented again five days later with worsened respiratory distress and recurrence of pleural effusion. Euthanasia was elected.

Gross Pathology:

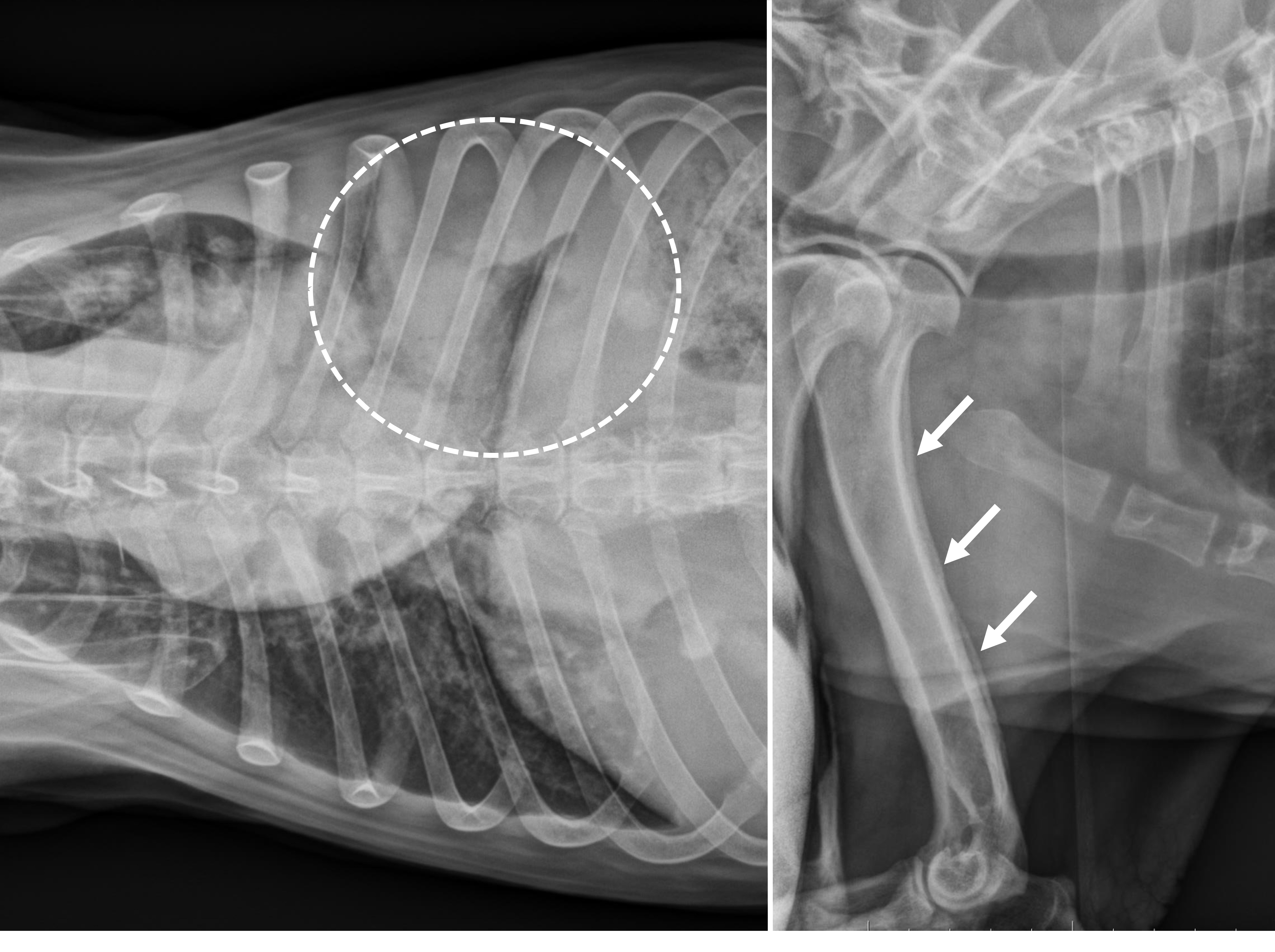

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed splenomegaly with abnormal echogenicity. Thoracic radiographs showed pleural effusion, loss of silhouette sign, and nodular interstitial pattern of the lungs. Thoracocentesis drained out approximately 1.15 litters of serosanguineous fluid from each side. On thoracic radiographs, after thoracocentesis, a persistent opacity was noted in the left caudal lung field. On skeleton radiographs, marked thickening and deformity of long bones with periosteal new bone formation was noted on distal bones of both front and hindlimbs, including the humerus, radius, carpus, tibia, ulna, metatarsal, and metacarpal bones.

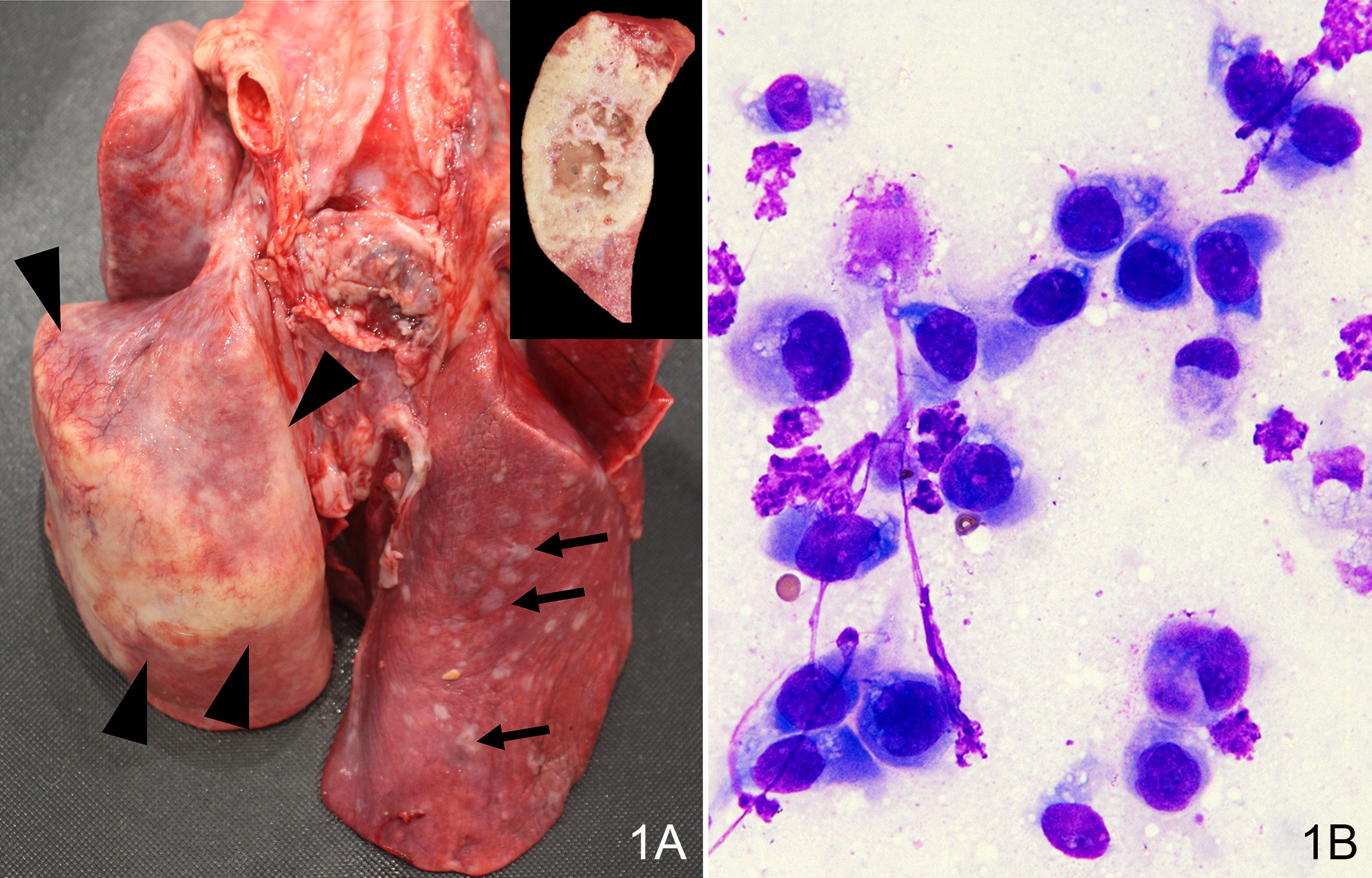

On autopsy, approximately 90% of the left caudal lung lobe was infiltrated by a raised, moderately firm, irregularly shaped tan-white mass, 10-cm in largest diameter, with areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, and mucus on cross-sections. The rest of the lung lobes contained multifocal white raised nodules up to 1 cm in diameter. The costal, mediastinal, and diaphragmatic pleura contained foci of white fibrotic plaques and adhesions to the pericardium. The pericardium was diffusely thickened with multiple coalescing white raised nodules. The distal esophagus near the cardia was thickened and had a 7-cm-diameter cystic lesion containing yellow viscous fluid. The spleen was attached to the omentum and contained a 2.5 cm round nodule near the attachment site. The caudal pole of the left kidney contained multiple raised grey to brown nodules extending to the renal cortex and appeared to be cystic on cross sections.

Laboratory Results:

In the past four months before the last consultation, serial hematologic and serum chemistry analysis during routine checkups showed a combination of mild mature neutrophilia (13.44 X 103 neutrophils/μL; reference interval, 3.00 X 103 to 12.00 X 103 neutrophils/μL), mild non-regenerative anemia, and mild hyperglobulinemia (5.6 g/dL; reference interval, 2.3 to 5.2 g/dL). On serologic qualitative test (Snap 4Dx Plus test, IDEXX laboratories Inc), the dog tested negative for heartworm disease, ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, and anaplasmosis.

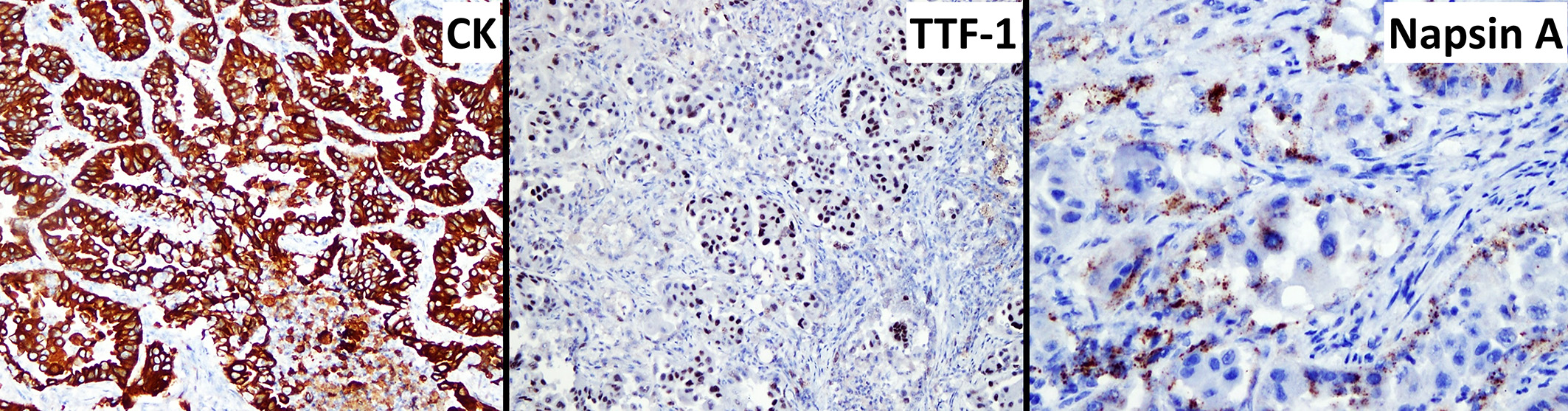

Table 1: Immunochemistry panel (lungs)

|

Marker |

Results |

|

Cytokeratin |

80-90% positivity |

|

Thyroid transcription factor 1 |

60-75% positivity |

|

Napsin A |

40% positivity |

Microscopic Description:

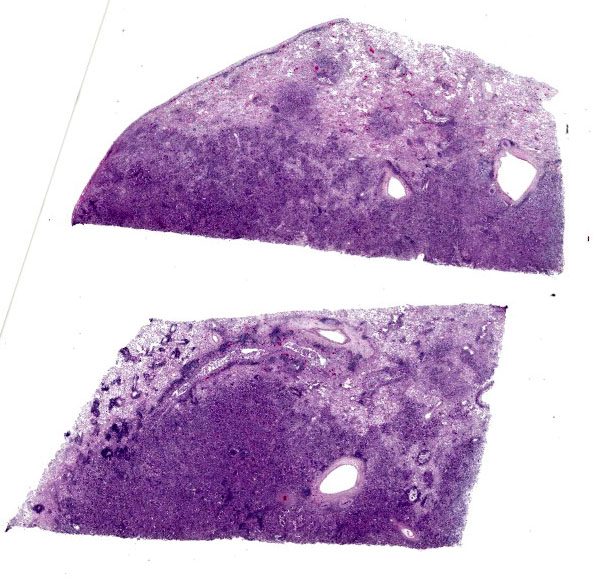

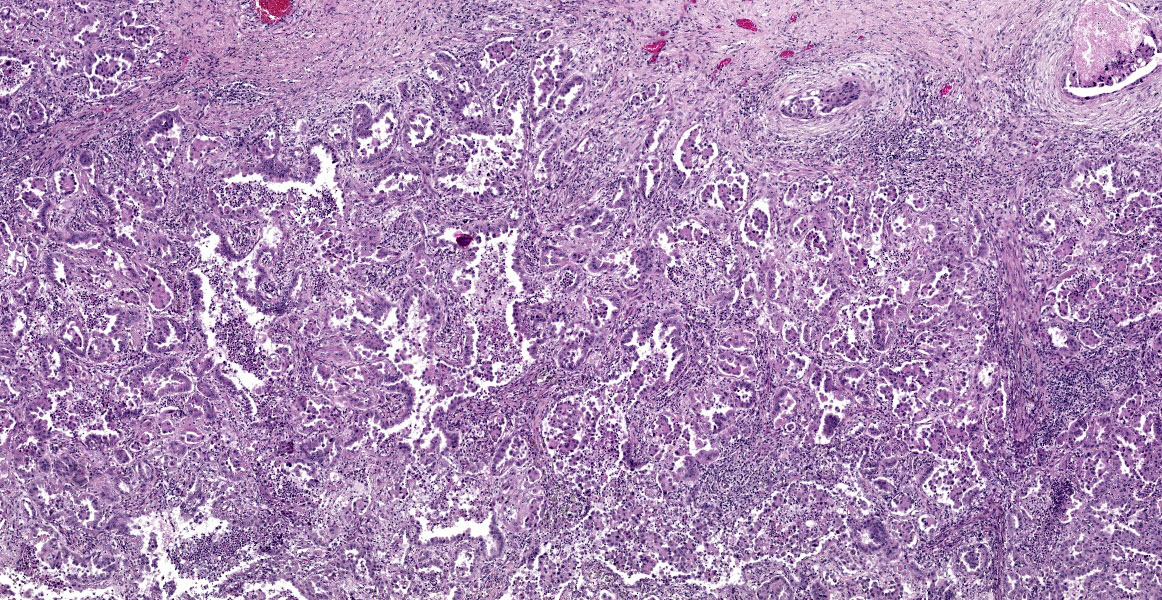

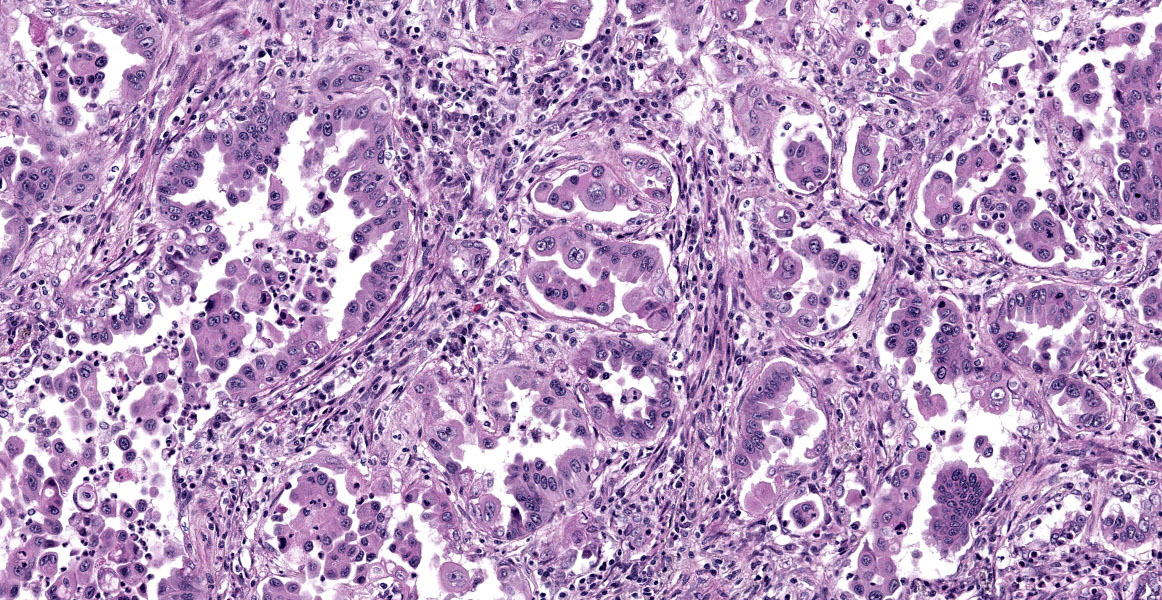

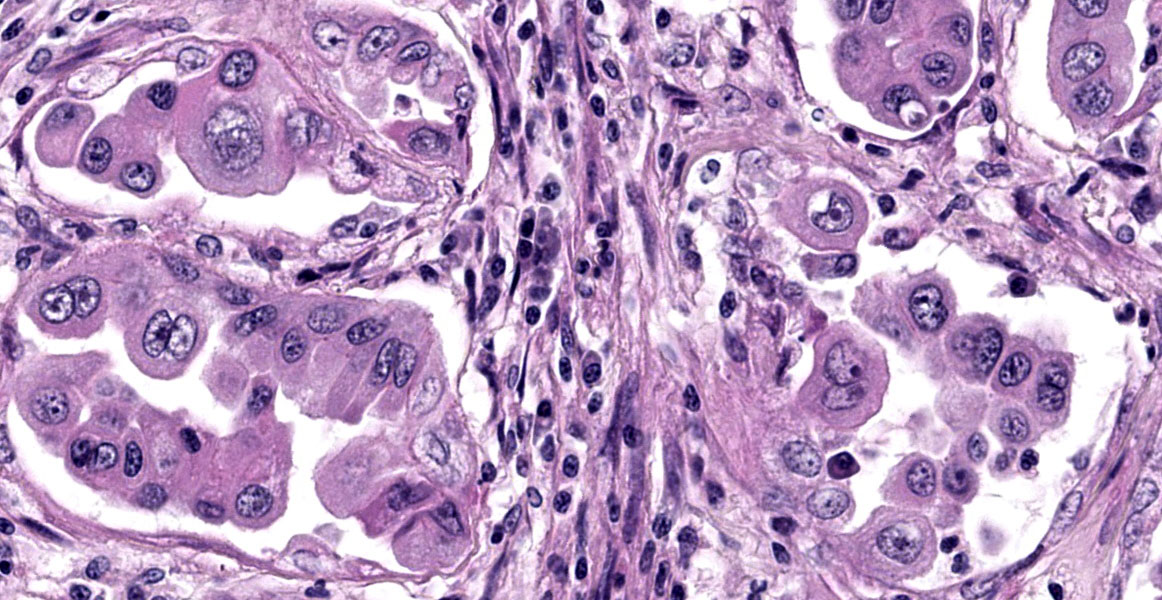

Lungs: focally and extensively effacing the pulmonary parenchyma is a nonencapsulated, non-demarcated infiltrative neoplasm forming islands, tubules, and acinar structures and loss of polarity with intraluminal papillary projections, supported by a prominent fibrovascular stroma, admixed with areas of necrosis and inflammation characterized by a moderate to high number of viable and degenerate neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells with the odd apoptotic cell. The neoplastic cells are pleomorphic (columnar to polyhedral) and lined the remnant of pulmonary airways with round to oval and basal nuclei. Moderate to high anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, often karyomegaly, and multinucleation with up to three nuclei are noted in the cell population. The cytoplasm of these cells is eosinophilic, finely granular to vacuolated. Mitotic count is 14 per 2.37 mm2 with atypical mitotic figures. Satellite neoplastic cell clusters are seen in the airways (mostly bronchioles), and lymphovascular invasion is also present. Adjacent to the neoplasm, inside alveolar spaces, there are many foamy macrophages. Diffusely the pleura is expanded by a moderate amount of fibrovascular tissue.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Pulmonary adenocarcinoma, acinar and papillary type.

Contributor’s Comment:

Respiratory distress in dogs can be associated with a variety of conditions, including congestive heart failure, upper airway obstruction, and pulmonary tumors. A multimodal approach is often required to investigate the cause of a dyspneic dog. Besides clinical history and physical examination, thoracic radiographs are considered the most important diagnostic test for pets with lung disease because imaging studies can provide a wealth of information on the presence, location, and intensity of the abnormality to guide differential diagnosis and diagnostic plans.1 Though fine-needle aspiration of the pulmonary parenchyma can be viewed as a relatively invasive technique, it is inexpensive and safe and its result turnaround period is fast and should be considered when evaluating animals with a nodular lung pattern noted on imaging studies.

Primary lung tumors are relatively uncommon in domestic animals. However, pulmonary adenocarcinoma is the most commonly diagnosed primary pulmonary tumor in dogs.4,6 The most frequent clinical sign associated with pulmonary carcinoma in dogs was coughing (52%), followed by dyspnea (24%), lethargy (18%), and weight loss (12%).5 However, in the same survey, 25% of the pulmonary carcinoma cases were incidental findings with no evident clinical signs of respiratory disease before diagnosis.

The lung is also a frequent site for tumor metastasis, and it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate primary pulmonary neoplasms from metastatic neoplasms originating from another location. Immunohistochemistry on thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and Napsin A are recommended to confirm the diagnosis of primary pulmonary neoplasia.7 In the present case, within the lungs, the pulmonary adenocarcinoma had spread through bronchial invasion and re?aspiration with intra?airway seeding in other lobes and lymphovascular invasion The neoplasm also disseminated to the pericardium and esophageal serosa, most likely through direct extension. The fibrous pleuritis was thought to be from the rubbing effects of the neoplasm between the pulmonary and parietal pleura. The hypertrophic osteopathy demonstrated by the thickening of cortical bones is a common paraneoplastic syndrome associated with thoracic space-occupying lesions,6 of which the exact mechanism is still unknown. The combination of hyperglycemia and mild mature neutrophilia supports that the patient was under stress and, in combination with the mild non-regenerative anemia, likely represented a result of chronic disease, such as cancer.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Biomedical Sciences?

Ross University School of Veterinary?

Medicine, St. Kitts, West Indies?

www.veterinary.rossu.edu?

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Dr. Taryn Donovan who is the head of Anatomic Pathology at the Animal Medical Center (AMC) in New York City. The conference cases had a decidedly cardiopulmonary emphasis with the first case being an opportunity to revisit the nomenclature of pulmonary neoplasms. Conference participants noted that the exact pattern of this adenocarcinoma was difficult to pin down with examples of papillary, acinar, and lepidic patterns all within the same neoplasm though this distribution was hardly uniform (figures 1-4 and 1-5). Dr. Donovan emphasized that morphology has diagnostic significance in the human literature3 though data (and relative importance) is still being weighed in domestic animals. In particular, lepidic patterns (growth along a pre-existing alveolus) may be important if it is the only or predominant pattern as the lack of disruption of the existing pulmonary architecture may include some benign diagnoses such as bronchioalveolar hyperplasia and less aggressive neoplasms (in situ and minimally invasive carcinomas) that carry a better prognosis.3

Conversely, patterns that disrupt existing pulmonary architecture (e.g. papillary) are far more likely to be associated with an invasive neoplasm and poorer prognosis. Although not conducted for this case, a Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain for elastic fibers may help to illustrate this concept as papillary patterns will lack elastin fibers. Conference participants also discussed micropapillary patterns which are noted to confer the worst prognosis though this nomenclature has not caught on in the veterinary literature. Dr. Donovan described this pattern as ‘florettes’ with clustering of small numbers of neoplastic cells within alveolar spaces that lacked the more robust stalk of supporting stroma of a true papillary pattern (figure 1-6). Participants also noted evidence of lymphovascular invasion in section with neoplastic cells within a lymphoid vessel, though distinguishing this from an acinar pattern with surrounding myofibroblastic stroma (and an adjacent micropapillary focus) prompted some careful second looks among the group. Dr. Donovan noted 50% of canine and 38% of feline cases in a recent literature meta-review noted a papillary pattern as the predominant morphology of primary pulmonary tumors among the articles4 reviewed.

As the contributor notes, delineating the origin of pulmonary masses requires consideration of both primary and metastatic neoplasia. We ran IHCs for AE1/3, TTF-1, CK7, Napsin A, vimentin, and P40. Our results mirrored the contributor’s (figure 1-7). Neoplastic cells were also modestly immunoreactive for CK7, but not for P40 (marker for squamous differentiation). Altogether, these findings confirm the diagnosis of a primary lung adenocarcinoma. One interesting feature of this case was that select neoplastic cells also expressed vimentin, consistent perhaps with a change in phenotype i.e. epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)2, though this can also be a feature of poorly differentiated carcinomas as well. EMT of type II pneumocytes is coordinated via cytokines in response to disruption of normal lung architecture – in neoplasia, this also is associated with increased ability of transitioning cells to invade.2

Lastly, this case features ancillary diagnostics that are worth a quick look. The contributor provides a solid example of hypertrophic osteopathy (figure 1-1) and representative cytology of a lung aspirate (figure 1-2) that tie this case together.

References:

1. Cohn LA. Diseases of the Pulmonary Parenchyma In: Ettinger SJ, Cote E,Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine 8ed: Elsevier Health Sciences 2016.

2. Kobayashi K, Takemura RD, Miyamae J et al. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of novel pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell lines established from a dog. Nature Sci Rep 13, 16823 (2023).

3. Kuhn E, Morbini P, Cancellieri A, Damiani S, Cavazza A, Comin CE. Adenocarcinoma classification: patterns and prognosis. Pathologica. 2018;110(1):5-11.

4. McPhetridge JB, Scharf VF, Regier PJ, et al. Distribution of histopathologic types of primary pulmonary neoplasia in dogs and outcome of affected dogs: 340 cases (2010-2019). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2021;260:234-243.

5. Ogilvie GK, Haschek WM, Withrow SJ, et al. Classification of primary lung tumors in dogs: 210 cases (1975-1985). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1989;195:106-108.

6. Wilson DW. Tumors of the respiratory tract In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in domestic animals. Ames Iowa, USA: Wiley Blackwell, 2017;467-498.

7. Ye J, Findeis-Hosey JJ, Yang Q, et al. Combination of napsin A and TTF-1 immunohistochemistry helps in differentiating primary lung adenocarcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in the lung. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2011;19:313-317.