WSC 2023-2024, Conference 25, Case 4

Signalment:

Age and breed unspecified ram (Ovis aries).

History:

During mating, the animal would start shaking and mating could not continue. Since this happened several times, the animal was euthanized and submitted for necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

The subcutaneous tissue of the ventral part of the abdomen, preputium, and penis was affected by severe suppurative inflammation in the form of large encapsulated abscess.

Laboratory Results:

Bacteriological culture examination showed an increase in the mixed bacterial flora in which Corynebacterium spp. predominated. Species identification was done by the MALDI-TOF method which confirmed that the species belonged to Corynebacterium xerosis.

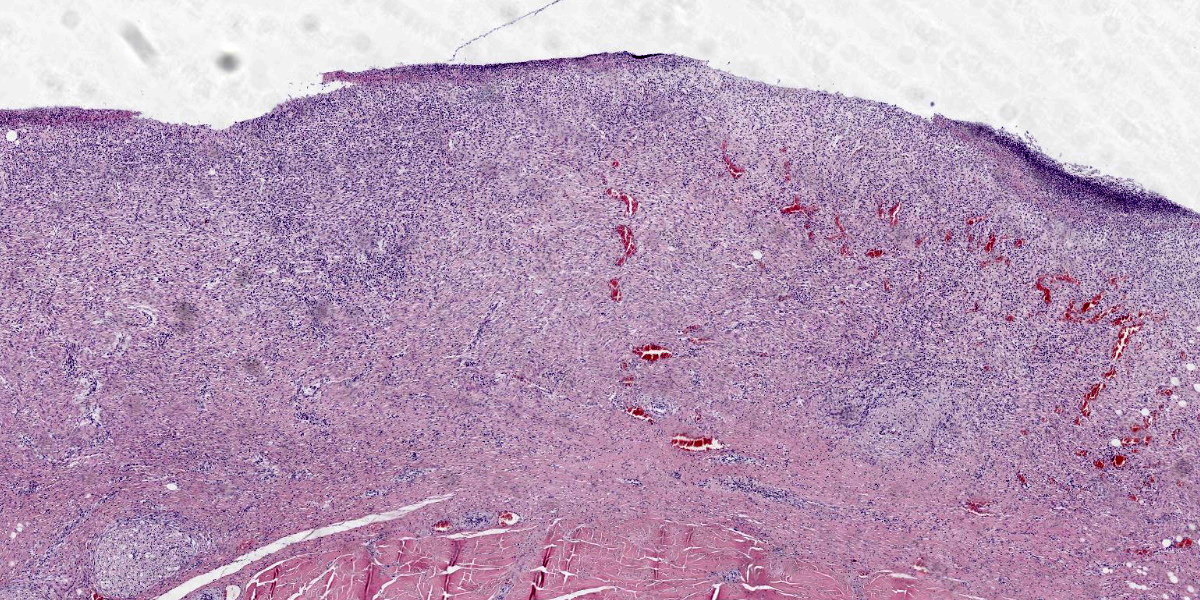

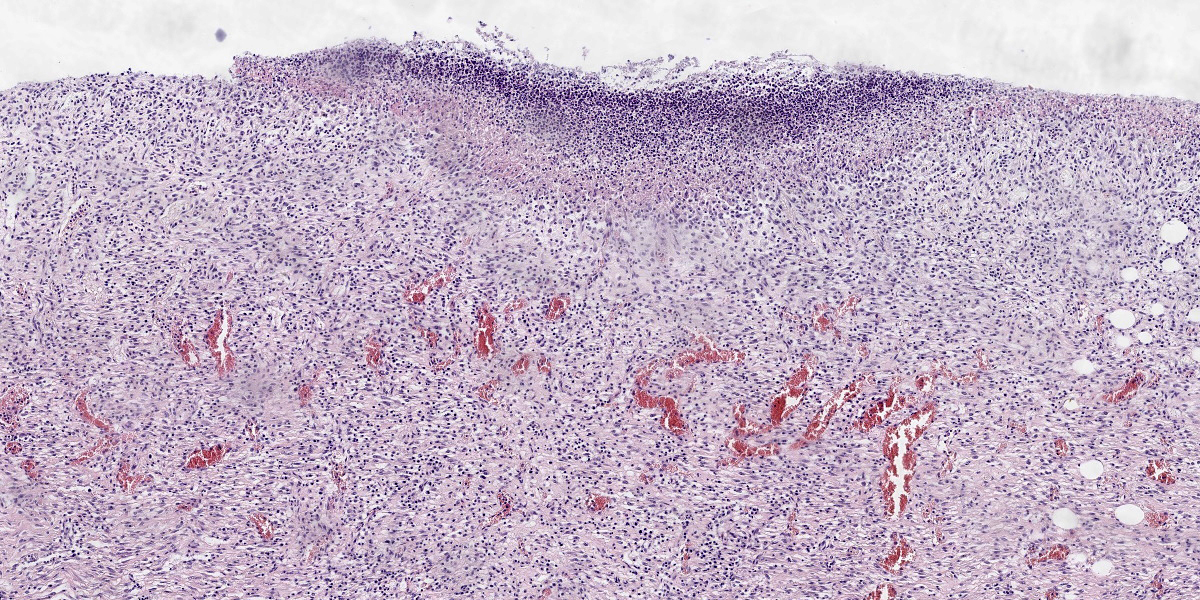

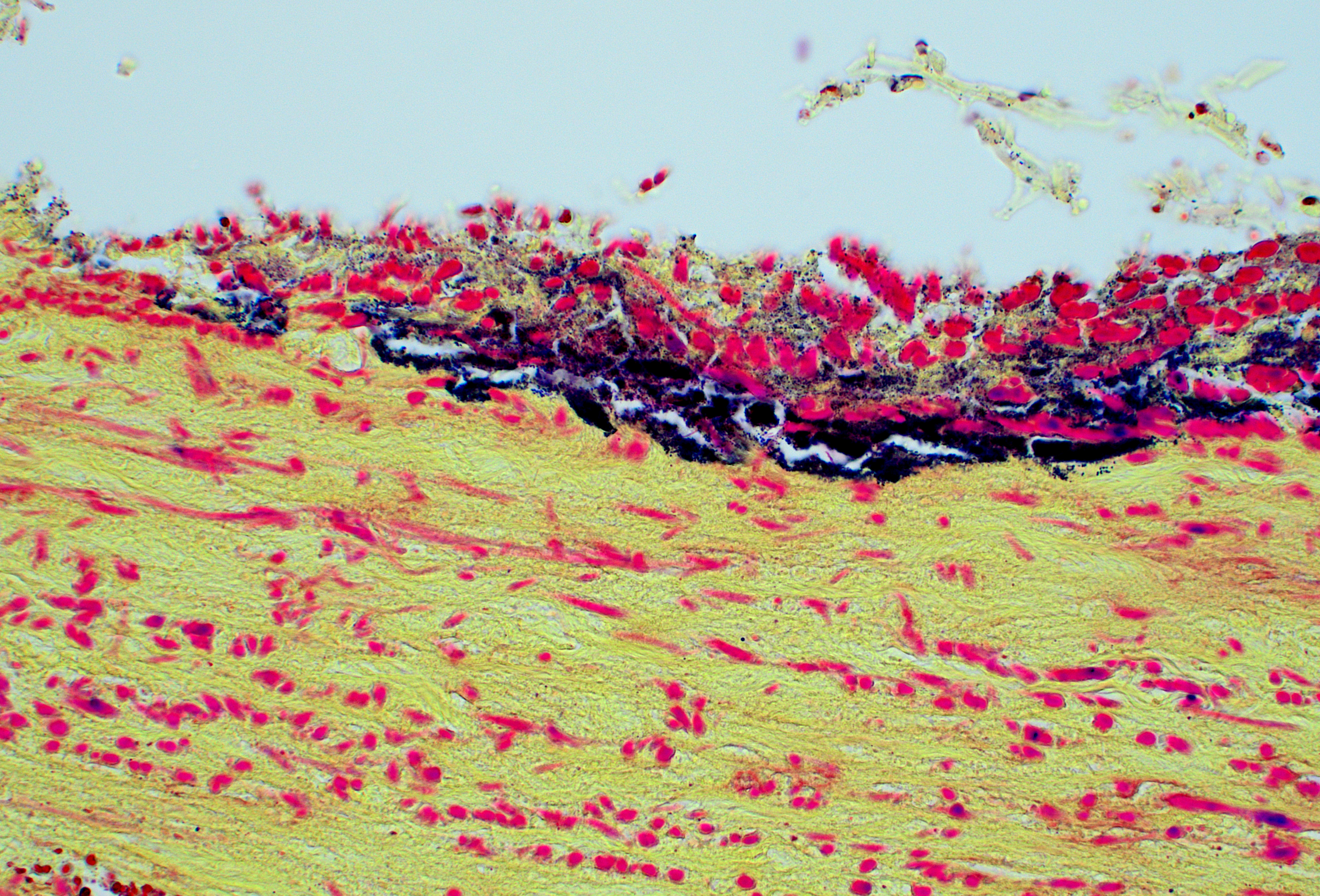

Microscopic Description:

Penis (glans): The most outer layer (penile mucosa) is replaced with amorphous eosinophilic material admixed with cellular debris mainly composed of degenerate neutrophils (necrosuppurative inflammation). There are multifocal colonies of coccobacillary bacteria on the surface. The lamina propria is diffusely infiltrated with larger numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and low numbers of neutrophils. The amount of inflammatory infiltrate decreases toward the internal parts of the penis (corpora cavernosa, corpus spongiosum, and urethra), which do not show pathological changes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Penis (glans): Balanitis, necrosuppurative, subacute to chronic, focally extensive, severe with intralesional coccobacillary bacteria.

Contributor’s Comment:

Rams can develop a range of lesions of the penis and prepuce and inflammation is common pathology. Inflammation of the penis is phallitis, that of the head (glans) of the penis is balanitis, and inflammation of the prepuce is posthitis. It can be of viral and bacterial etiology, but foreign materials can also cause inflammation.3 Although in our case the bacteriological examination showed an increase in mixed bacterial flora with a predominance of Corynebacterium spp., we believe that the isolated Corynebacterium xerosis (C. xerosis) played a role in the pathogenesis of this condition.

The genus Corynebacterium, which currently has more than 110 validated species, is highly diversified. It includes species that are of medical, veterinary, or biotechnological relevance.1,7,9 The most common cause of cutaneous abscesses and caseous lymphadenitis (CLA) in sheep is Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Caseous lymphadenitis in sheep almost always follows a wound infection, usually a shearing wound.10 The sequence of events in progressive CLA is infection of a superficial wound, spread of infection to the local lymph nodes, which suppurate, and then lymphogenous and hematogenous extension to produce abscesses in internal organs. The progression is slow and may reach the bloodstream only in older animals, whereas in young animals the disease tends to be confined to the superficial lymph nodes, most commonly the precapsular and precrural.10

Corynebacterium xerosis is a commensal organism normally present in the skin and mucous membranes of humans.2 It is considered an unusual pathogen, but it is able to cause endocarditis, skin infections, and other illnesess like maternal ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection, pneumonia, ear and brain abscess, and vertebral osteomyelitis.1,2,5,12 Corynebacterium xerosis grows in colonies of 0.2–1.0 mm in diameter that are brown-yellowish in colour, slightly dry in appearance, and non-haemolytic when cultured in blood agar. Microscopically, C. xerosis appears as irregularly stained, pleomorphic gram-positive rods presenting club-like ends.4

Infections with Corynebacterium xerosis in animals are rarely described. It has been isolated in pure culture from normally sterile organs of animal clinical specimens. C. xerosis was isolated from the joint of a pig suffering from a subcutaneous abscess and from a goat liver suspected to have paratuberculosis.11,12 The case for C. xerosis producing a clinical cutaneous abscess in sheep was reported in Mexico in 2016 and C. xerosis strain GS1 was isolated from a liver lesion with caseous nodules from a yak.4,12

Unlike C. pseudotuberculosis infection, the virulence factor that could contribute to the development of abscesses as a pathogenic toxin has not been reported in C. xerosis. The main factor of virulence and pathogenicity in C. pseudotuberculosis is the exotoxin phospholipase D, which is a permeability factor that promotes hydrolysis of the ester bonds in sphingomyelin in mammalian cell membranes, possibly contributing to the spread of bacteria from the initial site of infection to secondary sites through the lymphatic system to regional ganglia.6 This highlights the importance of carrying out further research regarding the mechanisms of infection present in this Corynebacterium species.4

In the presented case, the source of the infection remains unknown. Hernandez-Leon et al. discussed the possible epidemiology of C. xerosis in a sheep herd and hypothesized that a possible source of this bacterium could be pigs.4 The ovine production system where the sample was obtained was previously used for swine, a species where C. xerosis has been reported as a common pathogen. Additionally, sharp objects were widespread all over the facilities, which increased the chance of injury to the animals, opening a portal for microorganisms including C. xerosis.4,8,11 All these data indicate that C. xerosis has a certain clinical significance in veterinary medicine and that this bacterium should be considered as a possible cause of subcutaneous abscesses but also suppurative inflammation in other organs.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

University of Zagreb, Croatia

http://www.vef.unizg.hr/

JPC Diagnosis:

Penis: Balanitis, ulcerative, chronic, circumferential, severe, with granulation tissue and mixed colonies of bacteria.

JPC Comment:

As the contributor notes, Cornynebacterium xerosis is uncommonly isolated from veterinary patients and much of what is understood about this pathogen is extrapolated from human infections. Despite the novelty of the pathogen, however, this case presents a fairly straight-forward case of balanitis, which is typically accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages.3 Lymphocytes and plasma cells, and occasionally lymphoid follicles, are present within the normal preputial mucosa, and immunoglobulins derived from these plasma cells are present in preputial washes.3

In most cases of balanitis or balanoposthitis, ascribing pathogenicity to organisms isolated from a penile lesion is fraught with difficulty, as normal preputial bacterial flora may include a variety of nonpathogenic and potentially pathogenic bacteria such as Corynebacterium renale, fungi, mycoplasmas, ureaplasmas, chlamydial species, and a variety of protozoa.3 Attempting to determine which, if any, of these resident organisms is responsible for particular lesions has lead to conflicting research and a morass of speculation in most cases.

Dorper sheep and Leicester rams have a distinct, severe form of ulcerative balanitis which can also cause vulvovaginitis in ewes with whom they are mated.3 In the male, the condition is characterized by large, deep ulcers that occur on the ventral surface of the penis and typically progress to excessive granulation tissue and hemorrhage.3 Chronically, adhesions form between the penis and the prepuce as a result of necrotic and purulent material covering the head of the penis. Mated ewes develop shallow ulcers on the labia and posterior vagina. The etiologic agent responsible for this condition remains unknown.3

Rams and wethers may also develop “ulcerative posthitis of wethers,” commonly known as pizzle rot. The condition, which is unfortunately common, develops in the presence of urea-hydrolyzing bacteria, such as Corynebacterium renale, in animals that excrete urea-rich urine.3 Lesions progress from small areas of epithelial necrosis around the preputial orifice to more extensive geographic ulceration and granulation tissue that results in occlusion of the preputial orifice. The occlusion leads to the accumulation of urine and pus and, ultimately, to extensive internal ulceration of the prepuce, the urethral process, and the head of the penis.3

Balanitis occurs in all domestic species and is caused by a variety of familiar infectious agents, including bovine herpesvirus I in bulls; canid herpesvirus 1 and leishmaniasis in dogs; and Equid herpesvirus 1, Trypanosoma equiperdum (the causative agent of dourine), cutaneous habronemiasis, pythiosis, and cutaneous halicephalobiasis in horses.3

Conference participants began discussion of this case by noting the large colonies of bacteria, noting that these large colonies are a possible way to begin narrowing down the list of possible etiologic agents to one of the YAACSS agents (Yersinia, Actinomyces, Actinobacillus, Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus). The moderator cautioned participants not to read too much into the large colonies, as virtually any agent can form large colonies given enough time.

The agent isolated in this case is, of course, a member of YAACSS, albeit a somewhat enigmatic one, and discussion of this case largely centered on whether C. xerosis was the actual cause of the histologic lesions or just an opportunist. The question is largely rhetorical, and Dr. Bender used the discussion as a pivot to other Corynebacterium spp. of veterinary importance, including Corynebacterium renale and Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis centered largely on how to capture the unique appearance of this lesion and how to describe the bacteria. Participants felt the primary lesion was ulceration and that the granulation tissue was abundant enough to merit specific mention. Participants also felt that the bacterial population consisted of both cocci and bacilli and preferred to describe the bacterial population as mixed.

References:

1. Bernard K. The genus Corynebacterium and other medically relevant coryneform-

like bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50 (10):3152-3158.

2. Coyle BM, Lipsky BA. Coryneform bacteria in infectious diseases: clinical and laboratory aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3(3):227-246.

3. Foster RA. Male Reproductive System. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1194-1222.

4. Hernandez-Leon F, Acosta?Dibarrat J, Vázquez?Chagoyán JC, Rosas PF, Oca? Jiménez RM. Identification and molecular characterization of Corynebacterium xerosis isolated from a sheep cutaneous abscess: first case report in Mexico. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:358.

5. Krish G, Beaver W, Sarubbi F, Verghese A. Corynebacterium xerosis as a cause of vertebral osteomyelitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27(12):2869-2870.

6. McKean SC, Davies JK, Moore RJ. Expression of phospholipase D, the major virulence factor of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, is regulated by multiple environmental factors and plays a role in macrophage death. Microbiology (Reading). 2007;153(7):2203-2211.

7. Oliveira A, Oliveira LC, Aburjaile F, et al. Insight of genus Corynebacterium: ascertaining the role of pathogenic and non-pathogenic species. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1937.

8. Palacios J, Vela AI, Molin K, et al. Characterization of some bacterial strains isolated from animal clinical materials and identified as Corynebacterium xerosis by molecular biological techniques. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(9):3138–3145.

9. Soares SC, Silva A, Trost E, et al. The pan-genome of the animal pathogen Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis reveals differences in genome plasticity between the biovar ovis and equi strains. PLos One. 2013;8(1):e53818.

10. Valli T, Kiupel M, Bienzle D (with Wood RD). Hematopoietic System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kenedy & Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier; 2016:103-267.

11. Vela AI, Grac?a E, Fernandez A, Dominguez L, Fernandez-Garayzabal JF. Isolation of Corynebacterium xerosis from animal clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2242–2243.

12. Wen F, Xing X, Bao S, Hu Y, Hao B. Whole-genome sequence of Corynebacterium xerosis strain GS1, isolated from yak in Gansu Province, China. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019;8(37): e00556-19.