Signalment:

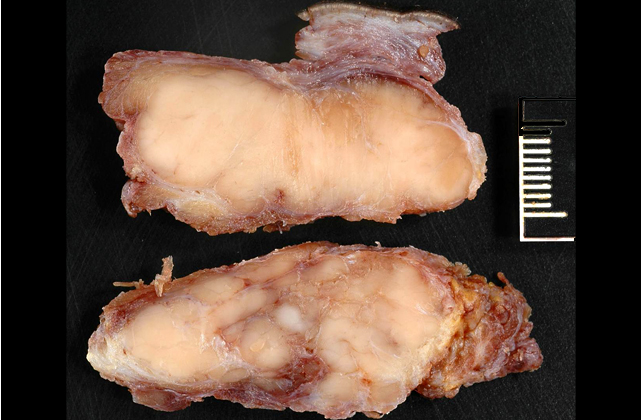

Gross Description:

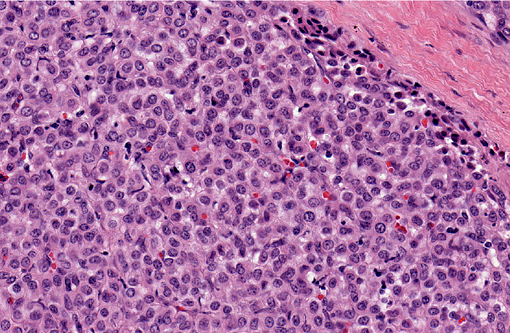

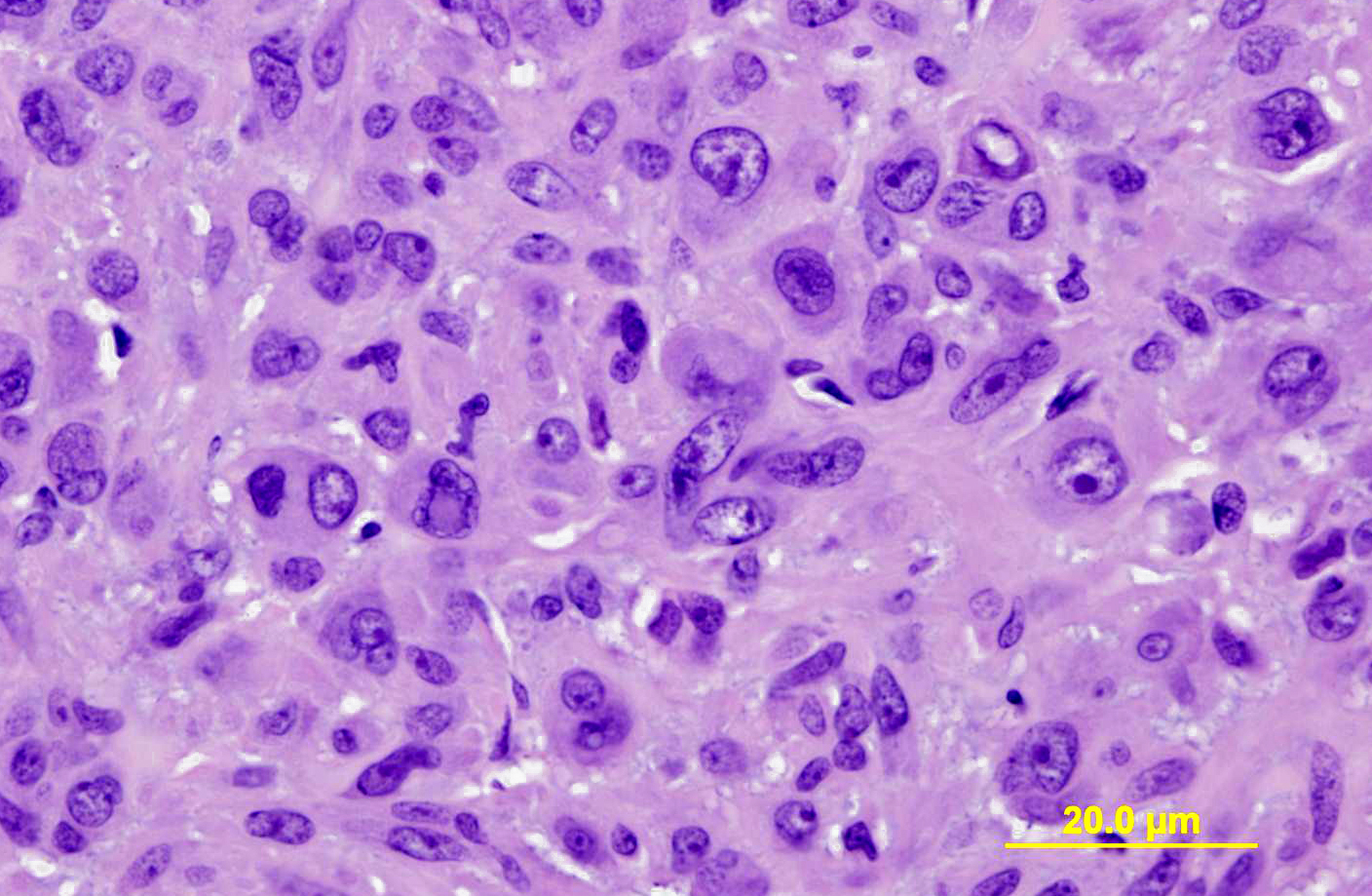

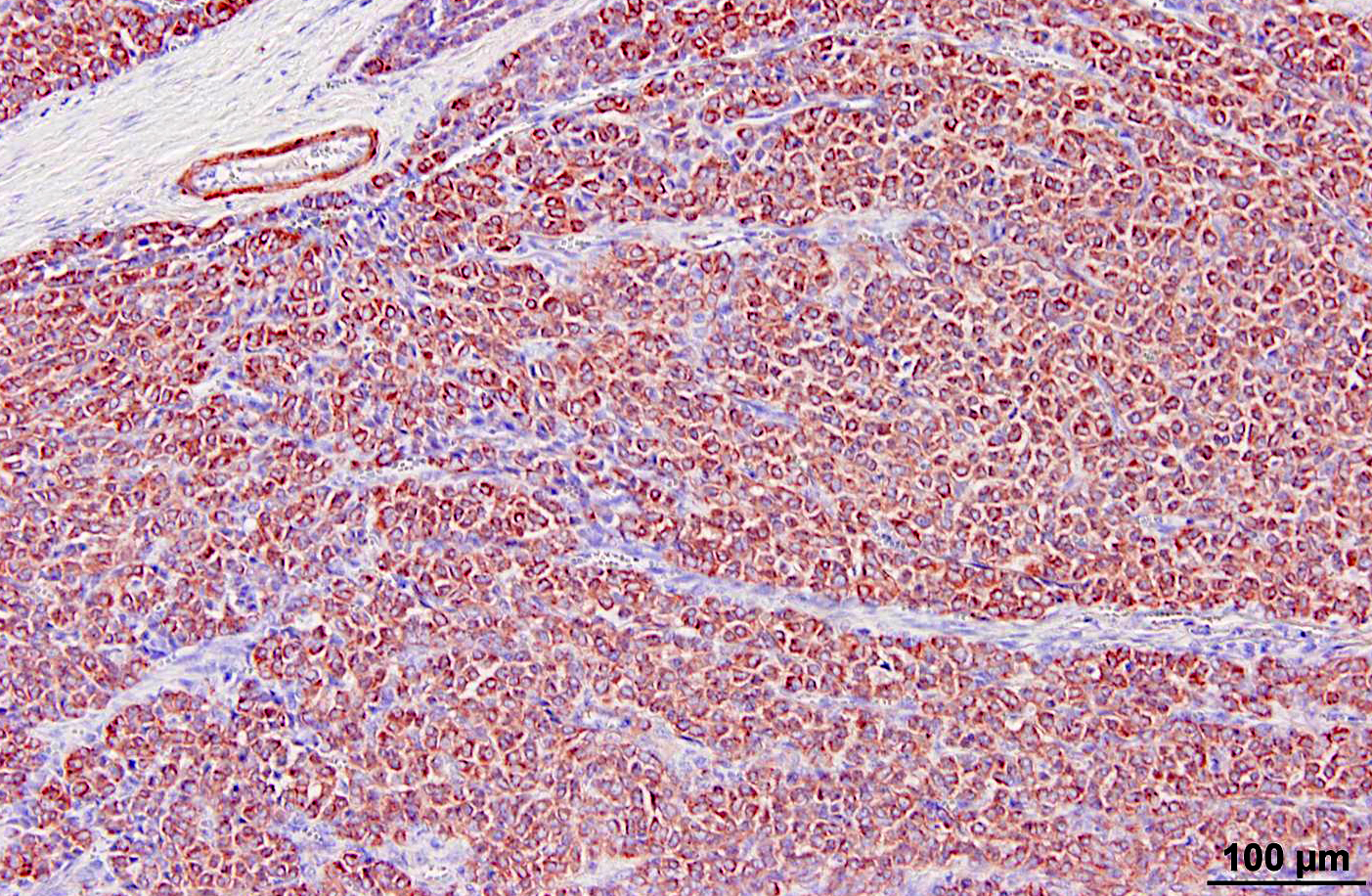

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

A feature of glomus tumors of the subungual region in humans, and less commonly of these tumors in other sites, is associated intense pain, presumably a result of innervation with substance P-containing nerve fibers.(6,10) In human medicine, this feature is diagnostically useful as few types of skin tumors are painful. Some degree of soreness was thought to be associated with this tumor, which was immediately adjacent to the facial nerve grossly and included several nerve fibers histologically. Interestingly, the other equine glomus tumor in the UC Davis case files was removed because it appeared to be painful to the horse when touched.

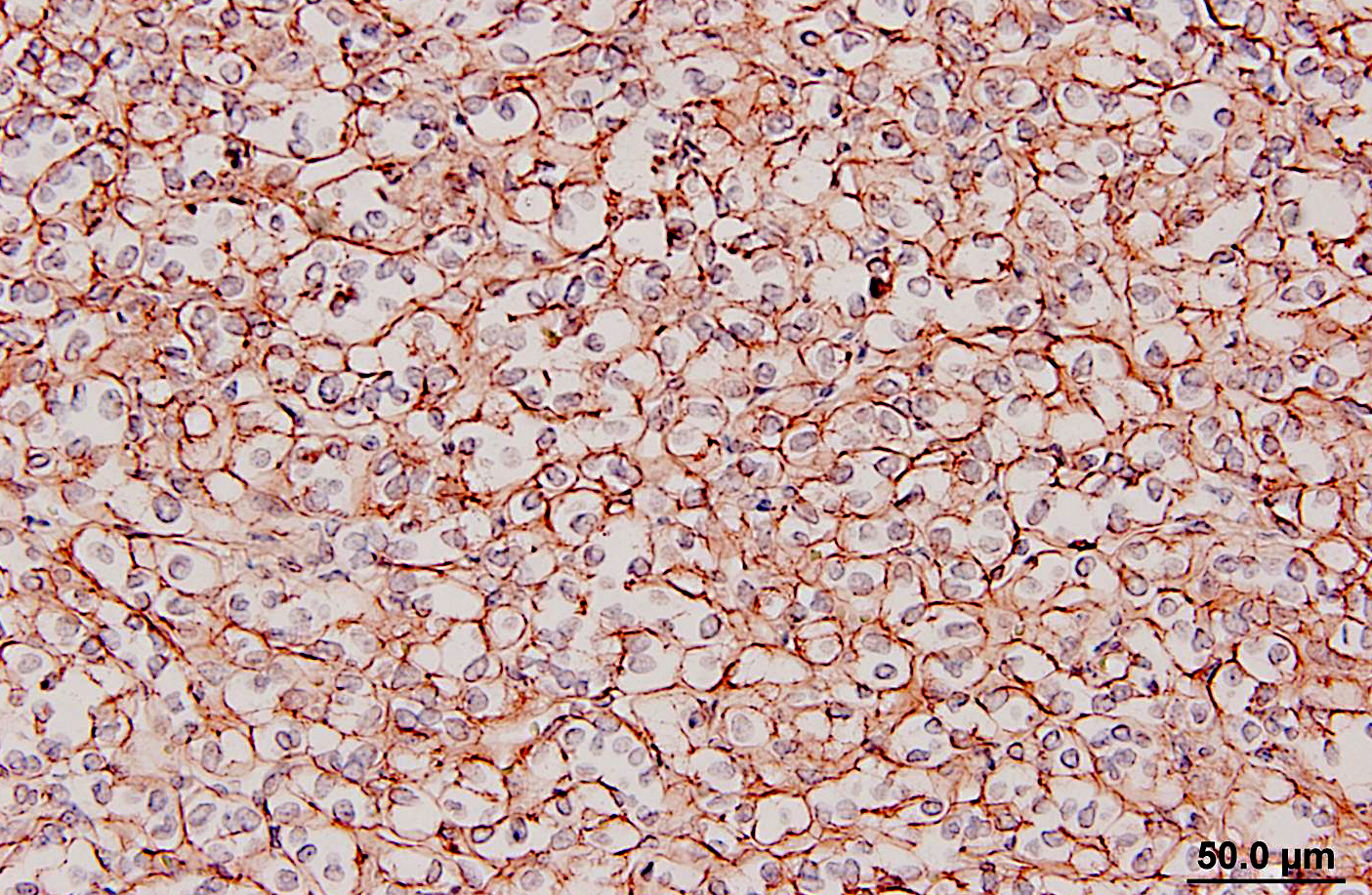

Glomus tumors in humans can be classified as solid, angiomatous, or myxoid types.(6) Except for multiple angiomatous glomus tumors in the bladder of a cow,(5) glomus tumors in animals, including this case, have generally been of the solid type.(2,3,7,9) They have several characteristic features which were seen in this case, including an intimate relationship with blood vessels, which may only be evident at the periphery, a round or cuboidal epithelioid cell shape with a punched out round nucleus and eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a network of basement membranes around each cell.(6,10) Immunohistochemistry for laminin was used in this case to demonstrate the basal lamina surrounding the neoplastic cells. Primary differential diagnoses for this tumor included trichoblastoma (the initial diagnosis), other epithelial neoplasms, or a neuroendocrine tumor, all of which were ruled out with additional immunohistochemical stains. Typical of glomus tumors, the neoplastic cells were positive for smooth muscle actin and vimentin and negative for cytokeratins, synaptophysin, factor VIII, and S100. The cells were variably positive for desmin, which has occasionally been reported in human and canine glomus tumors.(10)

In humans, malignant glomus tumors (glomangiosarcomas) are very rare, but have been defined by being larger than 2 cm with a deep location, having atypical mitotic figures, or having marked nuclear atypia and mitoses >5 per 50 high power fields (hpf). The tumor in this horse was considered to be malignant based on recurrence and rapid growth, invasiveness of deep tissues, large size, and areas of marked cellular atypia. Mitotic figures were also 8 per 50 hpf. Although clusters of neoplastic cells appeared to be present within vascular channels, true intravascular invasion was difficult to assess because of the close association of the tumor with blood vessels. No metastases were evident at presentation. The horse was treated with intralesional injections of cisplatin every 2-4 weeks post-surgery, with a total of 4 treatments planned. However, the mass recurred prior to the final injection, and the horse was euthanized (necropsy not performed at our institution).

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The differentiation between benignancy and malignancy is one of the most important roles of the pathologist, and tumors can sometimes defy typical classifications, so a best effort must be made on a diagnosis. Standard features to differentiate a benign tumor from its cancerous counterpart are the amount of differentiation or presence of anaplasia, the rate of growth, and the presence of local invasion and metastasis. The moderator commented that often with a surgical biopsy, which can be accompanied by a limited or no history as was the case with conference participants, the pathologist gets no information on metastasis, and local invasion may not be observed if no adjacent normal tissue is present(8).

Differentiation is the degree to which neoplastic cells resemble the cell or tissue of origin, both in appearance and function. Anaplasia is when the tumor is poorly differentiated, and it is believed that the undifferentiated cells with immature stem-cell-like properties with a loss of differentiation capacity. Anaplastic tumors may also exhibit lack of cell and nuclear uniformity, or pleomorphism; abnormal nuclear morphology with hyperchromasia, high nuclearto- cytoplasmic ratio, irregular shape, and variable nucleoli; bizarre mitoses or a high mitotic rate; loss cellular polarity with haphazard organization; tumor giant cells; and large areas of ischemic necrosis. The rate of growth in malignant tumors is often erratic, ranging from slow to rapid, and this is a difficult parameter to measure and use for the evaluation of malignancy. The local aggressiveness of a tumor is a good indicator of malignancy, as benign tumors are often expansile, while malignant tumors invade or efface the surrounding normal tissue. Malignant tumors are often poorly demarcated and lack an obvious cleavage plane. Finally, the presence of metastasis is an indisputable marker of malignancy, as benign tumors by definition to do not metastasize. Metastasis is achieved through either the seeding of body cavities and surfaces, as in carcinomatosis, or hematogenous or lymphatic spread. While generally carcinomas spread via lymphatic routes and sarcomas spread via hematogenous routes, the interconnectedness of the two vascular systems often blurs these lines. In lymphatic spread, neoplastic cells follow the natural route of lymphatic drainage. In hematogenous spread, veins are more easily penetrated by neoplastic cells, and spread usually occurs in the closest capillary bed. However, pulmonary capillary beds or primary pulmonary tumors allow easier access to arterial spread(8).

Despite the history of recurrence and rapid growth, conference participants felt the tumor was a benign entity based on the section presented in conference, and a discussion on the features of malignancy ensued. Cytomorphologic features of malignancy, such as areas of cellular atypia, atypical mitoses, and local invasiveness, lack of cellular differentiation, and evidence of metastasis, were not appreciated by conference participants The moderator commented that often with a surgical biopsy, limited or no history and the relatively small amount of tissue evaluated in a single histologic slide may make the differentiation between benign and malignant tumors elusive.

The moderator offered his approach to the characteristics of malignancy in order of most reliable to least as follows: By its very definition, evidence of metastasis means that a tumor is malignant. However, this information is often not present, and the next best feature to indicate metastasis is the presence of intravasation of the neoplasm, which underscores its aggressive nature. The next most reliable feature of malignancy is focal tissue invasion, characterized by neoplastic cells breaking through basement membranes, or inciting a desmoplastic response, inflammation or other features of host reaction. The least reliable criterion of malignancy is the cytologic appearance of neoplastic cells. When evaluating malignancy based on cellular features, evidence of cell behavior is more important that their appearance, such as the presence of bizarre mitotic figures; however, this can be difficult to completely ascertain based on the two-dimensional cut through a three-dimensional nucleus.

Glomus tumors are often difficult to characterize based on histomorphology alone, and this was an excellent example, having definitive features of a glomus tumor, including characteristic bulging into vascular channels.

References:

2. Dagli MLZ, Oloris SCS, Xavier JG, dos Santos CF, Faustino M, Oliveira CM, Sinhorini IL and Guerra JL: Glomus tumour in the digit of a dog. J Comp Path 128: 199-202, 2003

3. Furuya Y, Uchida K, Tateyama S: A case of glomus tumor in a dog. J Vet Med Sci 68: 1339-1341, 2006

4. Ludewig T: Occurrence and importance of glomus organs (Hoyer-Grossers organs) in the skin of the equine and bovine mammary gland. Anat Histol Embryol 27: 155-159, 1998

5. Roperto S, Borzacchiello G, Brun R, Perillo A, Russo V, Urraro C, Roperto F: Multiple glomus tumors of the urinary bladder in a cow associated with bovine papillomavirus type 2 (BPV-2) infection. Vet Pathol 45: 39-42, 2008

6. Rosai J: Soft tissues. In: Surgical Pathology, 9th ed., pp. 2288-2290. Mosby, St. Louis, MO, 2004

7. Shinya K, Uchida K, Nomura K, Ozaki K, Narama I, Umemura T: Glomus tumor in a dog. J Vet Med Sci 59: 949-950, 1997

8. Stricker TP, Kumar V. Neoplasia. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds., Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:262-271.

9. Uchida K, Yamaguchi R, Tateyama S: Glomus tumor in the digit of a cat. Vet Pathol 39:590-592, 2002

10. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR: Perivascular tumors. In: Soft Tissue Tumors, 5th ed., pp. 751-757. Mosby, St. Louis, MO, 2008