Signalment:

4-year-old, male beagle (

Canis familiaris). The dog presented with a two-month history of abdominal enlargement. Hepatomegaly was diagnosed. Two weeks prior to death, high fever (40.5 C), vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and lethargy were noticed. The dog arrived at the clinic severely weakened with bright yellow (jaundiced) mucous membranes and a tense abdomen. The patient died the next day.

Gross Description:

Severe jaundice and extreme enlargement of the lymphocentrum mesentericum craniale were the main postmortem findings. The lymph nodes showed a light brown to yellow cut surface with extensive necrosis; a differentiation between cortex and medulla was not possible. Other lymph nodes were moderately enlarged with a light brown cut surface. In vivo diagnosis of hepatomegaly was confirmed. The liver had a coarsely humped surface with multiple, confluent, light brown, not raised foci in the parenchyma of approximately one centimeter in diameter. Other findings included splenomegaly due to pulpy hyperplasia and a mild granulomatous nephritis.Â

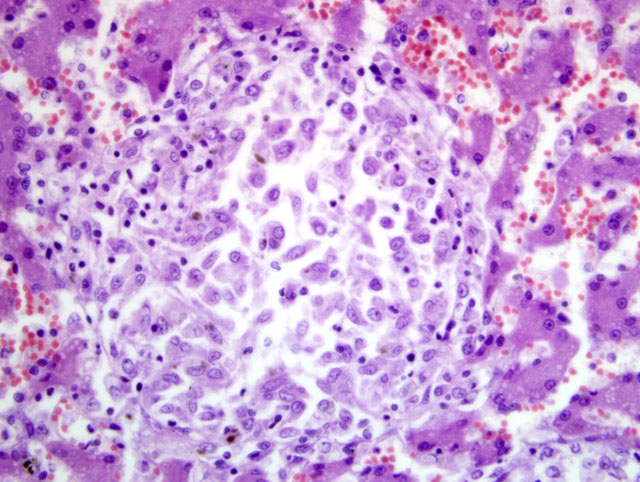

Histopathologic Description:

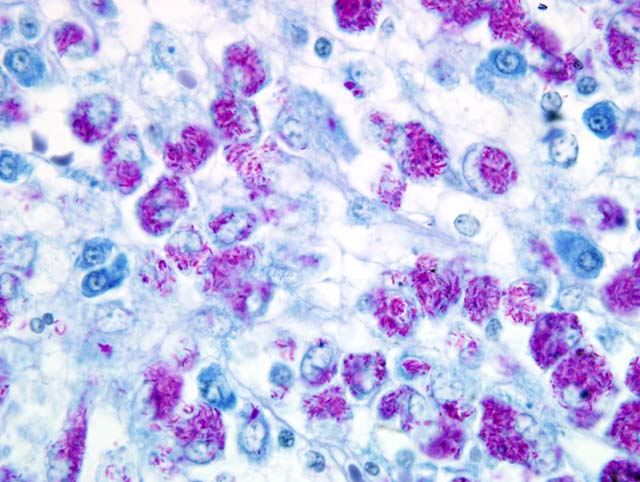

The histopathological examination of the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes of the lymphocentrum mesentericum craniale revealed an extreme infiltration of these organs with macrophages, which were characterized by a very large, euchromatic nucleus and a foamy, basophilic, granular cytoplasm, and sporadic giant cells of the Langhans type. The liver showed a severe interlobular, periportal, and intralobular infiltration with macrophages and a small number of lymphocytes causing almost total destruction of organ specific structures. Pressure atrophy of the surrounding liver tissue developed as a result of the extensive cellular invasion. Aside from the macrophage infiltration, the lymph nodes of the lymphocentrum mesentericum craniale showed central necrosis with multifocal calcification. Necrosis could not be found in other lymph nodes (e.g. lymphocentrum inguinale profundum, hepatic lymph nodes, lymphocentrum axillare), which were sinusoidally infiltrated with macrophages as well. Mild, circumscribed, predominantly perivascular infiltration with macrophages was present in both kidneys, the left ventricular myocardium and the lamina propria mucosae of the small intestine. The femoral bone marrow turned out to be myelopoetically active without any indication of osteomyelitis. The Ziehl-Neelsen stain revealed a massive presence of acid-fast rod-shaped bacilli in the macrophages infiltrating the liver, lymph nodes, spleen, kidneys, heart and intestine.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Severe granulomatous hepatitis with an abundance of intrahistiocytic acid-fast rod shaped bacilli (Ziehl-Neelsen stain); etiology consistent with

Mycobacterium avium (dog, beagle).Â

Lab Results:

Microbiological culture of the liver and kidneys revealed mycobacteria, which were identified as

Mycobacterium avium by PCR and reverse hybridization.Â

Condition:

Mycobacterium avium

Contributor Comment:

Disease due to

Mycobacterium avium occurs in mammals, especially as opportunistic infections, in the course of hereditary or acquired immune deficiencies. Generalized forms of tuberculosis as caused by

M. tuberculosis or

M. bovis have been rarely reported in dogs and cats in the last decades; but disseminated disease due to

M. avium and other atypical mycobacterioses are described more often in the current literature.(1,3-5,7)

A dog with

M. avium infection was mentioned in 1979 by Friend et al.(5) It is supposed that the infection can be caused by incorporation of infectious liver tissue of chickens or pigs. Both dogs and cats usually show a high resistance against

M. avium.(2-4,7) Therefore, hereditary immune deficiencies are thought to be responsible for the outbreaks described in the literature. Hereditary immune deficiencies are discussed in basset hounds (3) and miniature schnauzers, (4,7) which possibly go along with a high incidence of opportunistic infections in these breeds. Such a breed associated immune deficiency is, to our knowledge, not described in beagles.

In the presented case, it was not possible to find out if the dog was fed potentially infectious material. The route of infection remains unclear. Because the bacteria are prominent in the liver, intestine, and its lymph nodes, but not in the lungs, an oral infection is presumed. The formation of a complete primary complex with a rapid lympho-hematological spreading of the bacteria in the course of an early generalization is supposed. The massive periportal, intra- and interlobular infiltration of the liver with pathogen-bearing macrophages matches the description of the typical liver tuberculosis in carnivores according to Pallaske.(8) A similar morphology was seen in disseminated

M. avium infection in dogs.(2,4)

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, marked, with numerous intrahistiocytic acid-fast bacilli.

Conference Comment:

Because of the extent to which the granulomatous infiltrate effaces normal hepatic architecture in this case, many participants considered a neoplastic or atypical histiocytic proliferation in their initial differential diagnosis.Â

Mycobacterium avium and

M. intracellulare are two separate species that result in very similar lesions, and are thus referred to as

M. avium-intracellulare complex (MAC).(6) These nontuberculous, nonlepromatous mycobacteria are the most common etiologic agents in disseminated mycobacteriosis in dogs, although the disease remains uncommon overall.(7) Interestingly, they are also the most common opportunistic mycobacteria isolated from localized cutaneous infections in dogs and cats.(6) The lesions in the intestine and lymph nodes in this case, as well as in previously-reported cases, bear striking resemblance to those seen in sheep and cattle with Johne+�-�-�-�-�-�s disease. This is not particularly surprising, given that the causative agent of Johne+�-�-�-�-�-�s disease is

M. avium subsp.Â

paratuberculosis. In humans, disseminated opportunistic mycobacteriosis is usually associated with immunosuppression due to AIDS, and in reported canine cases, immunosuppression has been suspected, though not unequivocally proven. An alternate hypothesis for the pathogenesis in cases where multiple littermates are affected is exposure to a common source, possibly perinatally, as occurs in Johne+�-�-�-�-�-�s disease.(7)

References:

1. Bauer N, Burkhardt S, Kirsch A, Weiss R, Moritz A, Baumgaertner W: Lymphadeopathy and diarrhea in a miniature schnauzer. Vet Clin Pathol

31:61-64, 2002

2. Beaumont PR, Jezyk PF, Haskins ME:

Mycobacterium avium infection in a dog. J Small Anim Pract

22:91-97, 1981

3. Carpenter JL, Myers AM, Conner MW, Schelling SH, Kennedy FA, Reimann KA: Tuberculosis in five basset hounds. J Am Vet Med Assoc

192:1563-8, 1988

4. Eggers JS, Parker GA, Braaf HA, Mense MG: Disseminated

Mycobacterium avium infection in three miniature schnauzer litter mates. J Vet Diagn Invest

9:424-7, 1997

5. Friend SCE, Russell EG, Hartley WJ, Everist P: Infection of a dog with

Mycobacterium avium serotype II. Vet Pathol

16:381-4, 1979

6. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM: Skin and appendages.Â

In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer+�-�-�-�-�-�s Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 689-691. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

7. Horn B, Forshaw D, Cousins D, Irwin PJ: Disseminated

Mycobacterium avium infection in a dog with chronic diarrhoea. Aus Vet J

78:320-5, 2000

8. Pallaske G: Spezifische Entzundungen der Leber.Â

In: Handbuch der speziellen pathologischen Anatome der Haustiere, ed. Joest E, Band VI, Digestionsapparat 2, pp. 159-178. Verlag Paul Parey, Berlin, Hamburg, Germany, 1967