Signalment:

Gross Description:

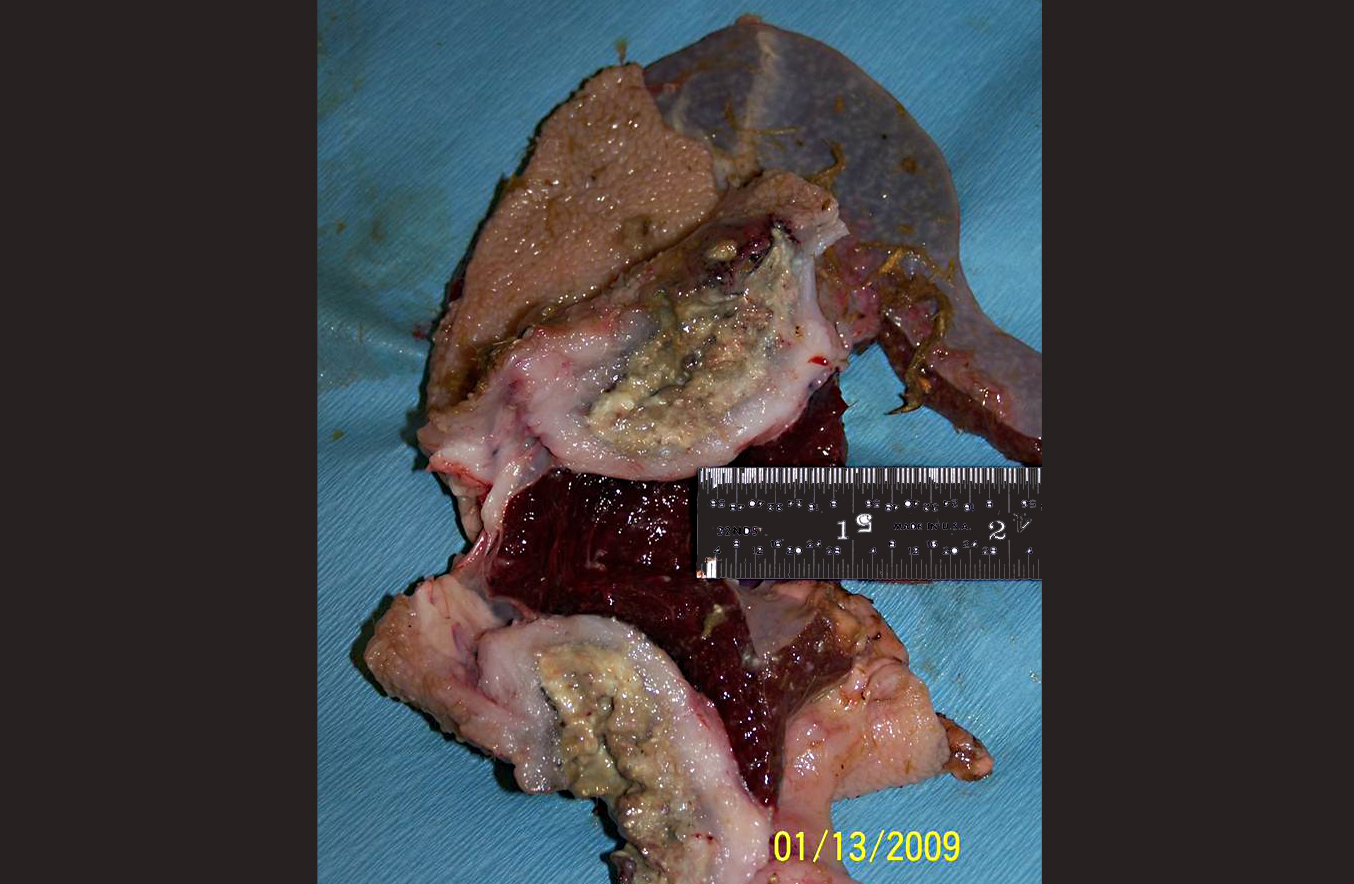

The rumen was filled with brown fluid and watery hay ingesta; expanding the wall of a saccule, there was a 5 cm long x 3 cm wide x 3 cm thick mass with an ulcerated, crateriform center containing greenish-white pus. There were multiple 2-4 mm in diameter erosions around the central crater. On cut section, the crateriform ulcer extended into the rumen wall forming a pus-filled pocket which was surrounded by an approximately 1-2 cm thick band of white, firm, glistening tissue. Adhered to the adventitial surface of the caudal vena cava in the mid-abdomen was a 1.5 cm in diameter, fluid-filled translucent, sac-like structure. Multiple lymph nodes including the mediastinal, mesenteric, and axillary, as well as several subcutaneous lymph nodes, were bright green and enlarged up to three times normal size.

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Rumen: Leiomyosarcoma, goat, caprine.

2. Nasal mucosa: Rhinitis, granulomatous, focally extensive, severe, with fungal hyphae and granulation tissue (histoslides not submitted).

3. Vena cava: Pseudocyst with larval cestode (cysticercosis) (histoslides not submitted).

4. Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, granulomatous, multifocal, mild, with intralesional nematode larvae, morphology consistent with Muellerius capillaries (histoslides not submitted).

5. Spleen, white pulp: Lymphoid depletion, diffuse, mild (histoslides not submitted).

Lab Results:

Positive: Vimentin; smooth muscle actin; S100 protein; desmin, multifocally positive.Â

Negative: Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP); myoglobin; CD117a (c-kit); discovered on GIST-1 (DOG-1).

Microorganism stains:

Lilli Twort (Gram stain): Gram-positive coccobacilli in small colonies on the periphery of large colonies of Gram-negative filamentous bacteria within the necrotic exudate.Â

Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS): Positive for long, filamentous bacterial rods forming club-shaped colonies; positive for fungal hyphae within the ulcers necrotic core.Â

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Smooth muscle tumors (leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma) of the alimentary system are the most common type of gastrointestinal stromal tumor reported in domestic animals.(3) In dogs, there are reports of leiomyomas arising from the wall of the gall bladder and outer muscle coats of the distal esophagus and stomach as well as reports of leiomyosarcomas arising throughout the digestive tract including the tongue, liver and spleen.(3,4,5) Likewise for cats, there are reports of leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas throughout the gastrointestinal tract.(3) Additionally, there are rare reports of leiomyomas and/or leiomyosarcomas arising in the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileocecal junction, rectum and omentum of horses as well as reports of a leiomyoma in the spiral colon of a cow and the omasum of a goat.(2,3,10) In general, leiomyomas of the digestive tract are more likely to be located in the upper rather than the lower tract.(5) To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a primary leiomyosarcoma arising from the rumen of a goat.

In contrast to the alimentary system, leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas are much more commonly reported in the urinary and reproductive tracts of laboratory and domestic animals. As such, there are reports in the veterinary literature of leiomyomas/leiomyosarcomas of the uterus in rats, rabbits, and guinea pigs; urinary bladder, vagina and uterus of cows; the scrotum, vagina, cervix, uterus, and urinary bladder of goats; the female genital tract, testis and urinary bladder of horses; and the urinary bladder, vagina, uterus, cervix and prostate gland of dogs and cats.(3,4,5,11)

Immunohistochemisty can be useful in differentiating and aiding in the diagnosis of neoplasms which have similar cellular morphology. In this case, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and peripheral nerve sheath tumor were considered differential diagnoses.Â

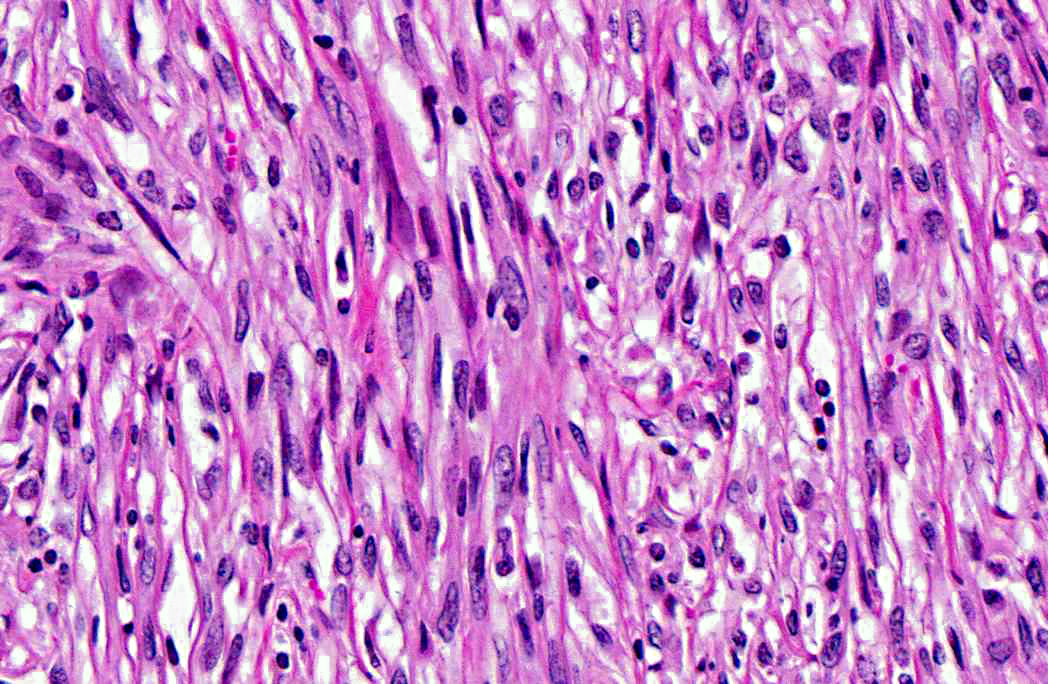

Leiomyomas/leiomyosarcomas typically express vimentin, desmin, and smooth muscle actin (SMA).(4) GISTs are believed to arise from primitive mesenchymal cells and, as such, can express vimentin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), and S-100 protein to varying degrees.(3,7,9,4,8,10) Additionally, in humans, GISTs also commonly express both the tyrosine kinase receptor CD117 (c-kit), and/or the chloride channel protein, discovered on GIST-1 (DOG1).(9) Peripheral nerve sheath tumors are composed of spindloid cells with characteristics of Schwann cells and are typically vimentin, S-100 protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) positive and SMA negative.(3) The neoplastic cells of the tumor described in this case expresses vimentin, desmin, SMA, and it does not express CD117, DOG1, or GFAP. These immunohistochemical findings support the diagnosis of a smooth muscle origin neoplasm; however, well-differentiated smooth muscle tumors do not typically express S100 protein as was seen in this neoplasm. There is a small percentage of human cases of leiomyosarcomas which do express immunoreactivity for S100 protein.(6)

Additional features of this lesion include large, up to 300 μm in diameter, radiating, club-shaped colonies of filamentous bacteria scattered throughout the necrotic exudate, often associated with mineralized debris (sulfur granules). Gram-negative and strong PAS staining of the large colonies of filamentous bacteria suggests infection by Fusobacterium necrophorum, a normal inhabitant of the alimentary tract and a common cause of necrobacillary rumenitis secondary to rumenal acidosis. Differentials for large colonies of filamentous bacteria include the higher forms of bacteria such as Actinomyces sp., Nocardia spp., or Arcanobacterium pyogenes; however, all three generally stain gram-positive. Additionally, with the aid of Gram stain, small colonies of gram-positive coccobacilli, suggestive of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, are also identified within the necrotic exudate.Â

Multifocally concentrated along the deep margin of the exudate are clusters and individually scattered fungal hyphae. These hyphae have a width of approximately 3-5 μm with regularly septate parallel walls and dichotomous acute angle or Y-shaped branching consistent with Aspergillus sp. Based on microscopic morphology, differential diagnoses for Aspergillus sp. include Fusarium spp., Pseudoallescheria boydii and Candida sp.

The yellow, firm, tissue-like mass partially adhered to the nasal respiratory mucosal epithelium was several centimeters long and partially occluded the respiratory passages on the right side of the head. This mass was composed of necrotic debris and a thick mat of fungal hyphae also consistent with Aspergillus sp. infection. Additionally, several lymph nodes were greatly enlarged and contained bright green pus suggestive of infection by Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, a known pathogen of this herd.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference participants began their discussion with a review of the histological morphology of ruminant forestomachs:

| Forestomach | Papillar structure | Presence/Absence of muscularis mucosae |

| Rumen | Long, finger or paddle-like papillae covered by stratified squamous epithelium | Muscularis mucosae is absent; no muscle is observed microscopically within ruminal papillae |

| Reticulum | Conical papillae project from crests of the honeycomb like folds, as well as from the bottom of the wells | Muscularis mucosae is present in the tips of the folds, but is discontinuous down the rest of the fold |

| Omasum | Papillae project from long folds | Muscularis mucosae is continuous projecting into omasal fold1 |

Conference participants went on to discuss the criteria for malignancy, asking the following questions:

1. Is there evidence of metastasis?

2. Is there evidence of local vascular or lymphatic invasion?

3. Is the neoplasm infiltrative?

4. Are there necrotic foci within the neoplasm?

5. Do neoplastic cells display cellular features of malignancy --Are the cells anaplastic?

6. Are the cells pleomorphic?

7. Is the chromatin clumped? Are the nucleoli large and/or irregular?

8. Is there a high mitotic rate? Are there bizarre mitoses?

9. Is there loss of cellular polarity or orientation?

10. Are the cells forming multinucleated cells?

These questions must be addressed whenever evaluating a neoplasm to differentiate benign from malignant tumors. The most important features of malignancy are the ability to metastasize systemically and/or the ability to invade local tissue. Malignant tumors owe their invasive nature to enhanced cell motility, increased protease production, and alterations in cell adhesions. Furthermore, malignant tumors tend to grow independent of exogenous growth factors and are resistant to environmental growth inhibitory signals; thus they have virtually unlimited growth potential. Malignant cells are also more adept at avoiding apoptosis and escaping the cytotoxic immune response and inducing angiogenesis than benign tumors, further enhancing their proliferative abilities.(8) In this case, the infiltrative nature of the tumor, as well as necrotic foci and cellular features of malignancy such as karyomegaly prompted a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma rather than leiomyoma.Â

References:

2. Collier MA, Trent AM. Jejunal intussusceptions associated with leiomyoma in an aged horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;182:819-821.

3. Cooper BJ, Valentine BA. Tumors of muscle. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 4th ed. Ames, Iowa; Iowa State Press: 2002:319-341.

4. Head KW, Cullen JM, Dubielzig RR, et al. Histological classification of tumors of the alimentary system of domestic animals. In: Schulman FY, ed. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumors of Domestic Animals. Second Series. Vol. 10. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology; 2003:35-36, 38, 79-81, 102-104.

5. Hulland TJ. Tumors of muscle. In: Moulton JE, ed. Tumors of Domestic Animals. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 1990:88-92.

6. Kempson RL, Fletcher CDM, Evans HL, et al. Tumors of the soft tissues. In: Rosai J, Sobin LH, eds. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Third Series. Fascicle 30. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology; 2001:239-256.Â

7. Lewin KJ, Appelman HD. Tumors of the esophagus and stomach. In: Rosai J, Sobin LH, eds. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Third Series. Fascicle 18. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology; 1996:145-150.

8. Kusewitt DF. Benign versus malignant tumors. In: Zachary JF, McGavin D, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:291.

9. Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Lasota J. DOG1 antibody in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1401-1408.

10. Schaudien D, Muller JMV, Baumgartner W. Omental Leiomyoma in a Male Adult Horse. Vet Pathol. 2007;44:722-726.

11. Whitney KM, Valentine BA, Schlafer DH. Caprine genital leiomyosarcoma. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:89-94.

*Research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other Federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 1996. The facility where this research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

**Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations above are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army or Department of Defense.