Signalment:

Male, Coimbra's titi (

Callicebus coimbrai)This monkey was kept at the zoological

park in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. It was found on the floor in a cage, prostrated

and hypothermic. It received emergency therapy with fluids, corticosteroids,

glucose, and heating, but died soon after the initial treatment.

Gross Description:

Grossly, the mesenteric lymph nodes were

hemorrhagic, the colon was dilated with multifocal and moderate hemorrhage in

the serosa. The colon content was hemorrhagic with a few blood clots, and large

amounts of fibrinous exudate. There was sand in the oral cavity, esophagus, and

stomach. The heart was mildly dilated. On the surface and cut surfaces of the

liver, there was a prominent lobular pattern. Kidneys and adrenal glands were

moderately congested.

Histopathologic Description:

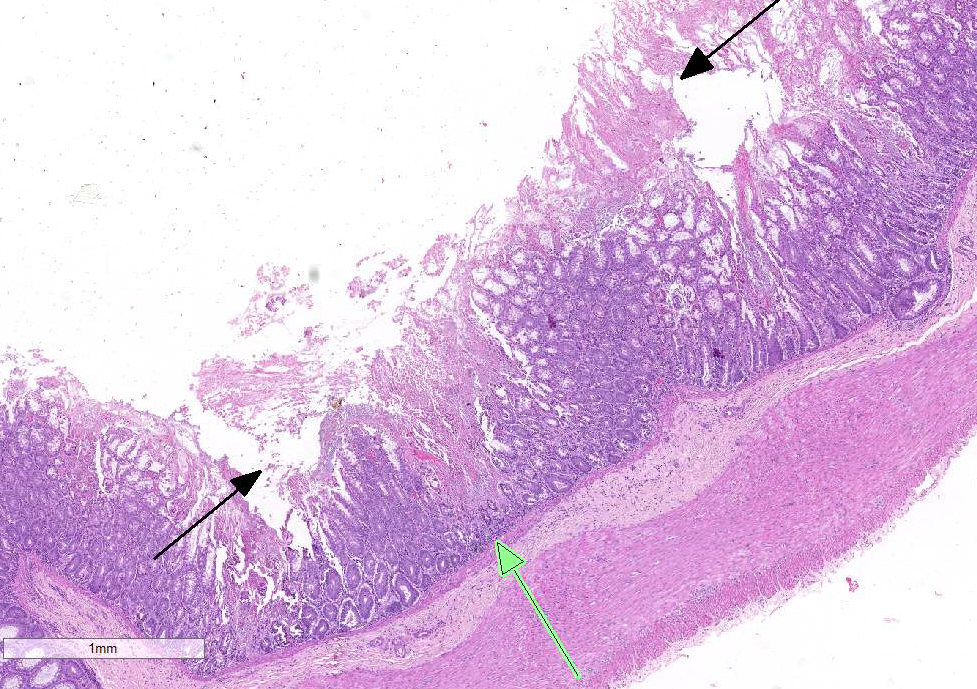

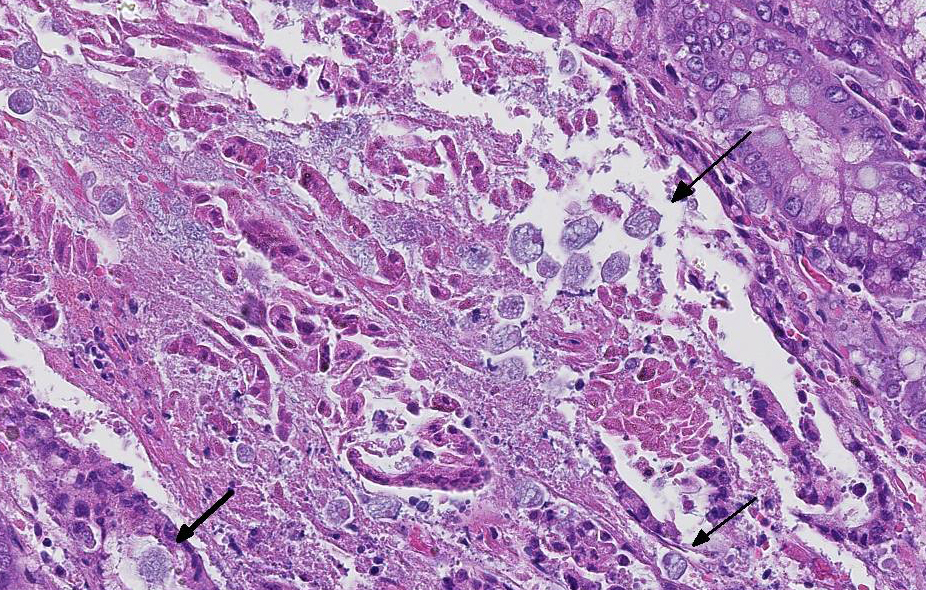

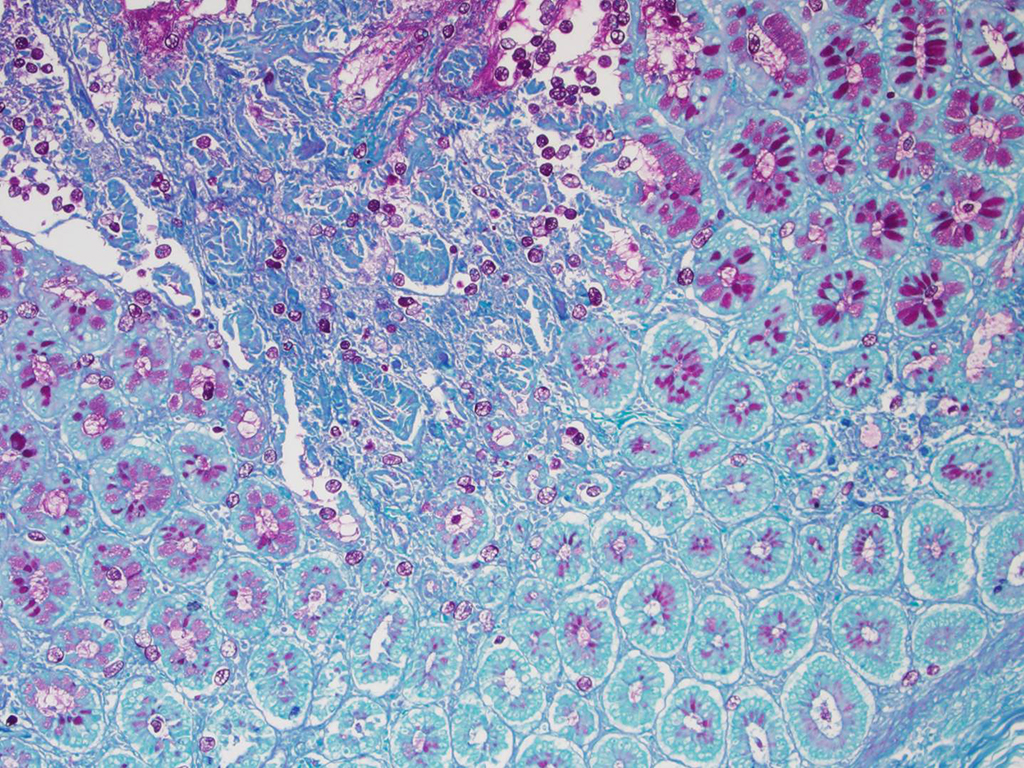

Multifocal to

coalescing and severe necrosis associated to multifocal and moderate hemorrhage was observed in the mucosa of

the colon. Myriads of round, 30-50 m

diameter, eosinophilic staining trophozoites were diffusely distributed in the

lumen, necrotic mucosa, crypts, and lamina propria of the colon. There was a

multifocal and mild infl-ammatory infiltrate composed of ly-mphocytes,

histiocytes and neutrophils in mucosa and submucosa. Some epithelial cells of

the colonic crypts had numerous circular, intensely basophilic cytoplasmic

structures, which were interpreted as apoptotic bodies.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Large

intestine, colon: Colitis, necrotizing, hemorrhagic, acute, multifocal to co-alescing,

severe with numerous protozoal organisms consistent with

Entamoeba

histolytica.

Lab Results:

None.

Condition:

Entamoeba histolytica, titi monkey

Contributor Comment:

Entamoeba

histolytica

is a protozoan parasite capable of invading the intestinal mucosa. It affects

other organs, mainly the liver, causing amebiasis.7 Entamoeba

dispar is mor-phologically similar. It also colonizes the human gut,

however it has no invasive potential.1 Both species are found of

non-human primates, such as monkeys, orangutans, and baboons.5

Most asymptomatic

infections found worldwide are now at-tributed to

Entamoeba dispar,

because it is non-invasive.

E. dispar is distinct but closely related to

E. histolytica. This non-invasive species has im-plications for

understanding the epidemiology of amebiasis.

3

In humans,

amebiasis is more common in developing countries. Bad conditions such as

overcrowding, poor education, co-ntaminated water, and poor sanitation favor

fecal-oral transmission of amoebas. This disease results in 70 thousand deaths

annually. Amebiasis is considered the fourth cause of death due to protozoa.

11A recent study revealed a high prevalence of

E. histolytica in

long-tailed macaques in the Philippines.

8 Captive monkeys infected

with

E. histolytica is a concern not only for the animal health risk,

but also due to the zoonotic nature of the disease.

4

The trophozoite,

which is the motile form of

E. histolytica, lives in lumen of crypts in

large intestine, where it multiplies and differentiates into cyst (resistant

form responsible for transmission). Cysts are excreted in stools, and may be

ingested by a new host through contaminated food or water. Upon ingestion of

infective cysts, parasites are released in terminal ileum, with each emerging

quadrinucleate trophozoite giving rise to eight uninucleated trophozoites.

Trophozoites may invade the colonic mucosa and cause dysentery.

3

There

are some molecules produced by

E. histolytica that are related to lysis

of the colonic mucosa: adhesins, amoebapores, and proteases. The parasite

attachment to colonic mucus blanket is due to a multifunctional adherent

lectin, preventing elimination in intestinal stream. Lectins are involved in

signaling cytolysis and in blocking the deposition of the injurious membrane

attack complex of complement. It maybe also participates in anchorage of the

ameba to proteoglycans, during invasion process.

3 Peptides of

E.

histolytica named am-oebapores destroy phagocytosed bacteria from the

microbiota that serve as the main nutrient source for the parasite. Whether

amoebapores play a role in the cytolytic event has not yet been proven.

Proteases produced by the parasite can degrade the extracellular matrix during

invasion and contribute in the lysis of target cells.

3

JPC Diagnosis:

Colon: Colitis, necrotizing, acute, multifocally extensive, marked with crypt abscesses, goblet

cell loss and numerous amoebic trophozoites.

Conference Comment:

E.

histolytica

colonizes the large intestine resulting in colitis and diarrhea,

and in some cases, may result in liver abscesses. E. histolytica has

two morphogenetic forms: the trophozoite and infectious cyst form. Ingestion

of viable cysts initiates infection and subsequent steps are discussed above. The

initial attachment to mucosal enterocytes by trophozoites, mediated through

adhesins and lectins, appears to be important in the initial pathogenesis and

apparently plays a role in cytotoxic activity.6 The host

inflammatory response contributes to tissue damage and may help facilitate

infection. Important cytokines involved in the host response include IL-8,

IL-6 and IL-1?; genes involved in cell proliferation also participate in the

response to infection. E. histolytica destroys host tissue and commonly

causes enterocyte apoptosis; trophozoites may ingest host cells following their

death. The mechanisms leading to host cell apoptosis are not completely

understood, but may involve production of reactive oxygen species and oxidative

stress. Other mechanisms which may be involved in cell death include amoebic

trogocytosis, where the parasite ingests fragments of host cell, resulting in

increases in intracellular calcium and cell death. 2 Other parasite

factors which are

involved in the pathogenesis include production of prostaglandin E2, which

increases sodium ion permeability through tight junctions, as well as secretion

of cysteine proteases which digest matrix components such as gelatin, collagen

type I and fibronectin. Epithelial barrier disruption also plays an important

role in infection.2 E. histolytica

trophozoites normally remain in the colonic lumen. However, in some cases, the

trophozoites invade the mucosa as well as mural blood vessels and lymphatics,

and eventually infect the liver. Ulcerative gastritis secondary to E.

histolytica infection has also been described in primates that have a

sacculated stomach, which is adapted for leaf eating and fermentation.

Similarly, E. histolytica-associated gastritis may also occur in

macropods (kangaroos and wallabies), which likewise have a sacculated stomach.

9 Trophozoites are observed in the mucosa and gastric glands, but may

also invade to the level of the submucosa, including vessels and

lymphatics.

E. histolytica may

also cause necrotizing and ulcerative colitis in dogs and cats (likely acquired

from a human source) although less commonly than in primates. In cats, E.

histolytica infection has been associated with severe necrosis of the colon

and cecum.9,10 It is apparently uncommon for infected dogs to shed

infectious cysts.

References:

1.

Diamond LS, Clark CG. A redescription of Entamoeba histolytica

Schaudinn, 1903 (emended Walker, 1911) separating it from Entamoeba dispar

Brumpt, 1925. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993; 40: 340–344.

2. Di

Genova BM, Tonelli RR. Infection strategies of intestinal parasite pathogens

and host cell responses. Front Microbiol. 2016; 7:256. doi:

10.3389/fmicb.

3.

Espinosa-Cantellano M, Martínez-Palomo A. Pathogenesis of Intestinal Amebiasis:

From molecules to disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000; 13(2):318.

4.

Feng M, Cai J, Min X, Yongfeng F, Xu Q, Tachibana H, Cheng X. Prevalence and

genetic diversity of Entamoeba species infecting macaques in southwest China. Parasitol

Res. 2013; 112:1529–1536.

5.

Feng M, Yang B, Yang L, Fu YF, Zhuang YJ, Liang LG, Xu Q, Cheng XJ, Tachibana

H. High prevalence of Entamoeba-infections in captive long-tailed macaques in

China. Parasitol Res. 2011; 109:1093–1097.

6. García MA, Gutiérrez-Kobeh L, López Vancell R. Entamoeba

histolytica: Adhesins and Lectins in the trophozoite surface. Molecules.

2015; 20:2802-2815.

7.

Martínez-Palomo A, Espinosa-Cantellano M. Amoebiasis: new understanding and new

goals. Parasitol Today. 1997; 14:1–3.

8. Rivera WL, Yason JA, Adao DE. Entamoeba histolytica and E.

dispar infections in captive macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in the

Philippines. Primates. 2010; 51:69–74.

9.

Stedman NL, Munday JS, Esbeck R, Visvesvara GS. Gastric amebiasis due to Entamoeba

histolytica in a Dama Wallaby (Macropus eugenii). Vet Pathol.

2003;40:340-342.

10. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and

Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO:

Elsevier; 2016:98-99.

11.

World Health Organization. 1998. The World Health Report 1998. Life in the 21st

century: a vision for all. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland.