Signalment:

Gross Description:

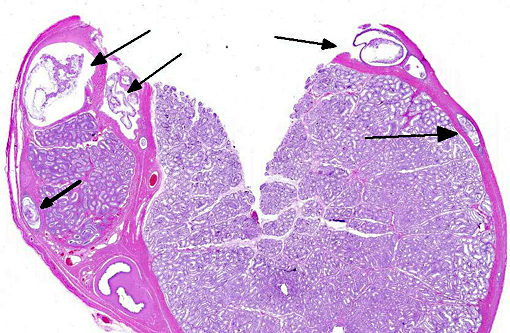

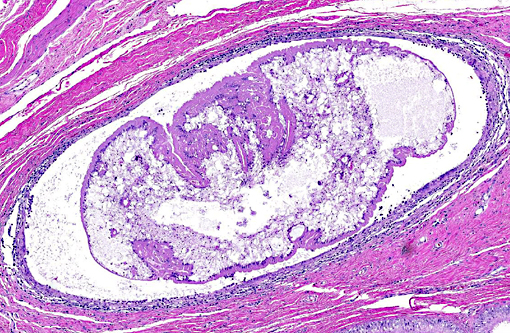

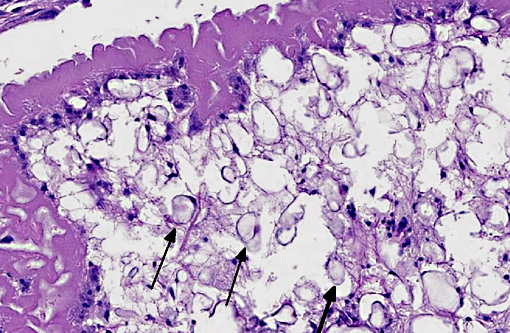

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Diagnosis and treatment of CPLC can be challenging. Clinical signs are vague and include lethargy, weight loss, vomiting and ascites.(4) Occasionally subclinical cases are identified during routine ovariohysterectomy or castration.(2) In two reported cases, scrotal swelling was among the initial presenting complaints.(10,13) Diagnostic procedures include radiology, showing changes indicative of diffuse peritonitis, and ultrasonography.(12) Cytologic examination of the ascites fluid or aspiration of affected organs often reveals intact tetrathyridia, acephalic forms or calcareous corpuscles.(3,9) Diagnosis of infection by Mesocestoides spp. can be confirmed by morphologic identification of tetrathyridia or by PCR.(2) Recommended treatment involves peritoneal lavage and long term treatment with fenbendazole(4) although other drugs, such as praziquantel, have also been used.(8) Prognosis after treatment depends upon the severity of infection at the time of diagnosis and upon how aggressively therapy is instituted.(2) At least some dogs experience recrudescence months after therapy is discontinued, although reinfection cannot be ruled out.(1) The dog in this report had a massive peritoneal infection and was treated aggressively with lavage and 30 days of fenbendazole therapy. Four months after initial diagnosis he presented with vomiting and radiographic evidence of intestinal obstruction. Partial necropsy after euthanasia revealed massive abdominal adhesions, but no samples for histopathology were collected; whether adhesions represented complications of healing peritonitis or recurrence of cestodiasis was not determined.

Although PCR to confirm Mesocestoides infection was not performed in this case, histologic lesions were consistent with previously reported cases. Characteristics of cestodes include a thick cuticle, acoelomate body and numerous calcareous corpuscles.(6) Although most of the metacestodes were degenerate, examination of multiple sections failed to reveal definitive scolices or suckers; it is likely, therefore that most of the organisms in this dog were the acephalic forms. Both tetrathyridia and acephalic forms have been described in cases of CPLC.(4)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The class of flatworms (Platyhelminthes) referred to as cestodes are more commonly known as tapeworms, and infect nearly every vertebrate species. Cestodes typically inhabit the gastrointestinal tract, to include the ducts of the liver and pancreas. They are generally of minor significance to the animal though they may reach spectacular size in some species (Consider the 60-foot long, Diphyllobothrium latum of man!). All tapeworms utilize at least two hosts to complete their lifecycle, and as the contributor concisely describes, some such as Mesocestoides spp. require more.

Adult cestodes are segmented into proglottids and both larvae and adults often contain suckers or hooks. All contain calcareous corpuscles which are of unknown function but most helpful in initially classifying the organism as a cestode. In this case, the corpuscles are shrunken and surrounded by a clear space which is likely a commonly observed artifact of fixations. Spirometra falls into the category with Diphyllobothrium of Pseudophyllideans. Mesocestoides are grouped with other common veterinary parasites such as Taenia, Hymenolepis, and Echinococcus in the Cyclophyllidean category characterized by four anterior suckers and muscles separating medullary and cortical regions.(6)

Since nearly all adult tapeworms are parasites of the digestive tract, those observed in tissue sections are usually larva. Along with the discussed sparganum and tetrathyridium larvae, most other larval forms have specific nomenclature. Pairing the appropriate larval and adult tapeworm species together can be an overwhelming challenge, though a focus on the following cestodes may cover those of greatest importance in veterinary pathology.

| COMMON VETERINARY CESTODE SPECIES | ||

| ADULT | LARVA | SPECIES WITH ASSOCIATED PATHOLOGY |

| Spirometra spp. | Sparganum (Plerocercoid) | Dog, Cat |

| Mesocestoides spp. | Tetrathyridium | Dog, Cat, NHPs |

| Rodentolepis nana, R. microstoma, Hymenolepis diminuta | Cysticercus | Rodent |

| Taenia taeniaformis | Cysticercus fasciolaris | Rodent |

| Taenia pisiformis | Cysticercus pisiformis | Rabbit, Dog |

| Taenia hydatigena | Cysticercus tenuicollis | Ruminants, Swine |

| Taenia ovis | Cysticercus ovis | Sheep |

| Taenia saginata | Cysticercus bovis | Cattle |

| Taenia solium | Cysticercus cellulosae | Swine |

| Taenia multiceps | Coenurus cerebralis | Sheep, Goat |

| Moniezia spp., Thysaniezia giardi, Stilesia globipunctata | Cysticercus | Ruminant |

| Anoplocephala perfoliata | Cysticercus | Horse |

| Diphyllobothrium spp. | Cysticercus | Fish--�âeating carnivore |

| Diplydium caninum | Cysticercus | Dog, Cat |

| Echinococcus granulosus | Hydatid cysts | Many |

| Echinococcus multilocularis | Hydatid cysts | Many |

References:

1. Barsanti JA. Mesocestoides infections: Recurrence or reinfection? JAVMA. 1999;214:478.

2. Boyce W, Shender L, Shultz L, et al. Survival analysis of dogs diagnosed with canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis (Mesocestoides spp.) Vet Parasitol. 2011;180:256-261.

3. Caruso KJ, James MP, Paulson RL, et al. Cytologic diagnosis of peritoneal cestodiasis in dogs caused by Mesocestoides sp. Vet Clin Path. 2003;32:50-60.

4. Crosbie PR, Boyce WM, Platzer EG, et al. Diagnostic procedures and treatment of eleven dogs with peritoneal infections caused by Mesocestoides spp. JAVMA. 1998;213:1578-1583.

5. Fuentes MV, Galan-Puchades MT, Malone JB. A new case report of human Mesocestoides infection in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:566-567.

6. Gardiner CH, Boynton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology/ American Registry of Pathology. Washington, DC. 2006:50-55.

7. Padgett KA, Boyce WM. Life history studies in two molecular strains of Mesocestoides (Cestoda: Mesocestoidae): Identification of sylvatic hosts and infectivity of immature life stages. J Parasitol. 2004;90:108-113.

8. Papini R, Matteini A, Bandinelli P, et al. Effectiveness of praziquantel for treatment of peritoneal larval cestodiasis in dogs: A case report. Vet Parasitol. 2010;170:158-161.

9. Patten PK, Rich LF, Zaks K, et al. Cestode infection in 2 dogs: Cytologic findings in liver and a mesenteric lymph node. Vet Clin Path. 2013;42:103-108.

10. Rodriguez F, Herraez P, Espinosa de los Monteros A, et al. Testicular necrosis caused by Mesocestoides in a dog. Vet Rec. 2003;153:275-276.

11. Topli N, Yildiz K, Tunay R. Massive cystic tetrthyridiosis in a dog. J Small Animal Med. 2004;45:410-412.

12. Venco L, Kramer L, Pagliaro L, et al. Ultrasonographic features of peritoneal cestodiasis caused by Mesocestoides sp in a dog and in a cat. Vet Radiol & Ultrasound. 2005;46:417-422.

13. Zeman DH, Cheney JM, Waldrup KA. Scrotal cestodiasis in a dog. Cornell Vet. 1988;78:273-279.