Signalment:

This heifer was found sick and treated with penicillin and banamine, but died. It was submitted for necropsy to the Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory at Washington State University.

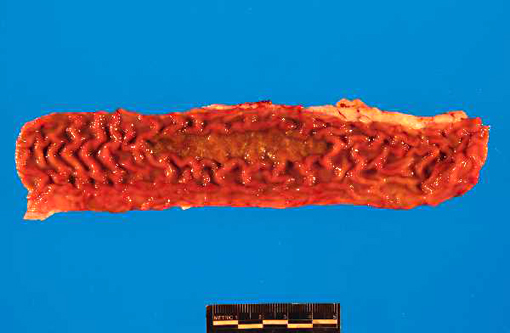

Gross Description:

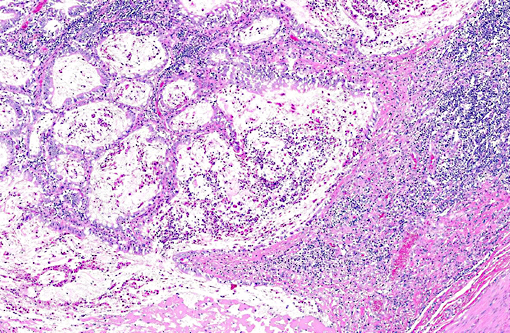

Histopathologic Description:

A replicate section immunostained for the presence of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) revealed positive immunoreactivity in the crypt epithelial cells and macrophages. Positive controls had appropriate immunoreactivity and a replicate slide stained with a non-specific antibody (isotype control) had no immunoreactivity in those areas.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

The sera from two herdmates of this heifer were tested by antigen ELISA for persistent infection with BVDV. Both were positive.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) is an RNA virus of the genus Pestivirus that causes a wide variety of clinical disease primarily in cattle which is its natural host.3 A highly mutable virus, BVDV has developed two primary genotypes, 1 and 2, with both cytopathic (cp) and noncytopathic (ncp) forms within each genotype. Type 1 genotypes are considered to be more prevalent but less virulent than type 2 genotypes, although exceptions occur. Cytopathogenicity in vitro does not correlate with virulence.

In na+�-�ve, immunocompetent non-pregnant cattle, infection with BVDV can cause mild clinical disease characterized by fever and leukopenia, or they may develop classic bovine virus diarrhea, including oculonasal discharge, oral erosions and enteritis. Highly virulent strains (usually type 2 genotypes) may cause acute, severe disease with high morbidity and mortality with lesions indistinguishable from mucosal disease (described later). Transiently infected or vaccinated cattle develop neutralizing antibodies that are protective against reinfection.

Infection of na+�-�ve pregnant animals can result in fetal loss, congenital defects or birth of live, persistently infected (PI), immunotolerant calves. Infected fetuses may be aborted or may develop hydrancephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia, thymic atrophy, osteosclerosis or cataracts and other ocular lesions. PI status requires infection of the fetus early in gestation (40 -125 days).(4) PI cattle are immunotolerant and do not develop antibodies to BVDV. They shed large amounts of virus and are an important source of infection for the herd. Detection and removal of PI animals is an important management strategy on cattle ranches. PI status can be detected by PCR for BVDV on buffy coats, but this does not distinguish from transiently infected cattle. Antigen ELISA on serum or ear notch supernatants, however, detects animals with high viral shedding and is the preferred method for screening for BVDV PI animals.5 PCR on pooled samples from ear notch supernatants, with subsequent individual testing on positive pools is an efficient way to screen large herds.(8)

PI calves are often unthrifty and most succumb to mucosal disease before 2 years of age. Mucosal disease occurs when a calf persistently infected with an ncp strain of BVD becomes infected with a similar cp strain, or when the ncp resident strain mutates to become cp. The classic clinical presentation of mucosal disease is a small calf with oculonasal discharge and severe diarrhea. Gross lesions include coronitis, nasal and oral erosions, and ulcerative lesions throughout the gastrointestinal tract, including esophageal ulcers and characteristic, severe enteric ulcerations overlying Peyers patches.(3,4) The epithelial necrosis and herniation of crypts into severely depleted Peyers patch lymphoid follicles is characteristic of BVD; rinderpest causes similar lesions but is distinguished by characteristic multinucleate syncytial cells with morbillivirus cytoplasmic inclusions.(3) Diagnosis of BVD can be confirmed by immunohistochemical demonstration of viral antigens within ulcerative lesions in the skin and throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The economic impact of the BVDV is significant, with the bulk of the expenses due to the acute transient infections which can compromise the immune system and exacerbate other bacterial or viral infections. Eradication efforts have been underway throughout Europe and in areas within the U.S. with restricted animal movement such as in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.(6) These efforts focus on identifying the beating heart of the disease, the reservoir and source of infection known as the persistently infected (PI) calf.

As the contributor describes in detail, the PI calf develops in-utero following exposure to the virus, specifically a non-cytopathic (ncp) strain. For the calf to become immunotolerant to BVDV, the virus must avert the immune system by infecting the fetus before the humoral immune system is fully developed (~125 days gestation). Also, the virus must suppress the innate immune response through inhibition of type I IFN signaling. Type I IFN signaling is normally stimulated through the recognition of viral double-stranded (ds) RNA via TLR 3 (as discussed in case I) or RIG-1. Non-cytopathic strains, which already have less dsRNA to begin with compared with cytopathic strains, achieve this suppression through the expression of Erns glycoprotein. Erns exhibits RNAse activity and degrades extracellular RNA, thus decreasing stimulation of TLR 3 and RIG-1. Similarly, the glycoprotein Npro degrades IRF-3 which is also involved in IFN signaling, though in conjunction with IRF-7 through TLR 7, 8, and 9.1 Expression of both Erns and Npro is necessary to induce persistent infection.(4) These underpinned mechanisms of disease pathogenesis elaborately correlate with the ncp strains ability and cp strains inability to produce a PI animal.

The difference between cp and ncp strains was demonstrated in vitro as the ability to induce apoptosis in bovine turbinate cells. This corresponds with the continual expression of NS3 protease in cp strains versus little to no expression in ncp strains. NS3 induces apoptosis through both intrinsic (caspase 9) and extrinsic (caspase 8) pathways. Activated caspase 8 incites apoptosis of B- and T-lymphocytes in ileal Peyers patches, which may correlate activation of the extrinsic pathway with the Peyers patch necrosis observed in this case. Additionally, the antiapoptotic BCL-2 protein is upregulated by ncp BVDV, which may also relate to the difference in disease manifestation between the two strains.(4)

Bovine pestivirus shares its genus with other prominent diseases of domestic animals such as Classical swine fever virus and Border disease virus of sheep. Additionally, a closely related virus that causes similar clinical presentations as BVDV has been circulating in Brazilian cattle with reports of cases in Europe and Asia as well indicating possible widespread dissemination. To date, this virus has been called Hobi-like, BVDV-3 or atypical pestivirus 2, and in time may add itself to the list of economically important Pestiviruses.

References:

1. Ackermann MR. Inflammation and healing. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:111-112.

2. Bauermann FV, Ridpath JE, Weiblen R, Flores EF. Hobi-like viruses: An emerging group of pestiviruses. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2013;25(1):6-15.

3. Brown CC, Baker DC and Barker IK. The Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th edition. Vol. 2. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:140-147; 149-151.

4. Brodersen BW. Bovine viral diarrhea virus infections: Manifestation of infection and recent advances in understanding pathogenesis and control. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:453-464.

5. Cornish TE, van Olphen AL, Cavender JL, et al. Comparison of ear notch immunohistochemistry, ear notch antigen capture ELISA and buffy coat virus isolation for detection of calves persistently infected with bovine viral diarrhea virus. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005;17:110-117.

6. Grooms DL, Bartlett BB, Bolin SR, Corbett EM, Grotelueschen DM, Cortese VS. Review of the Michigan Upper Peninsula bovine viral diarrhea virus eradication project. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;15;243(4):548-54.

7. Jarvinen JA, OConnor AM. Seroprevalence of bovine viral diarrhea virus in alpacas in the United States and assessment of risk factors for exposure, 2006-2007. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;15;245(6):696-703.

8. Kennedy JA, Mortimer RG, Powers B. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction on pooled samples to detect bovine viral diarrhea virus by using fresh ear-notch supernatants. J Vet Diagn Invest. 006;18:89-93.