Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 6, Case 3

Signalment:

23.5 year old female rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta).

History:

This monkey had acute, bilateral hind limb paralysis with intact patellar reflexes and an otherwise normal neurologic exam and was euthanized due to welfare concerns. Two years prior to euthanasia an adenocarcinoma was excised from the cecum.

Gross Pathology:

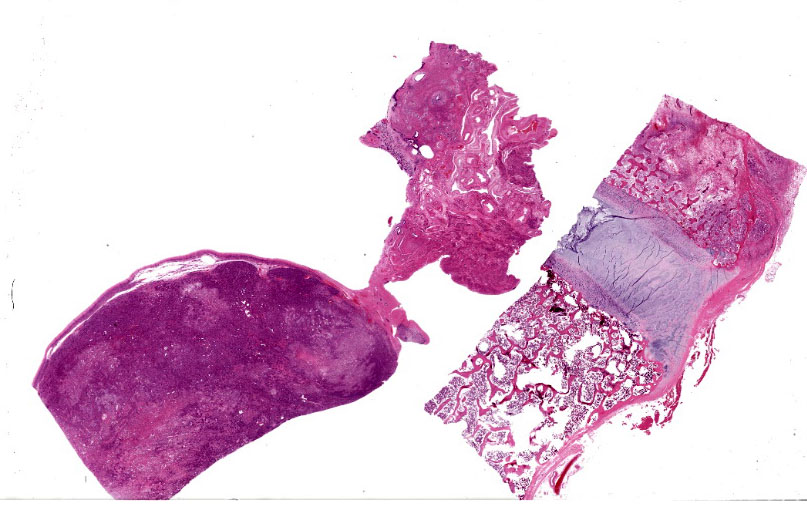

A 4.5 x 4 x 4 cm, 34.68 g tan to red firm mass and effaced the left ovary. On sectioned surface the neoplasm was mottled tan to pink with small, scattered areas of central hemorrhage and necrosis. The L1-L2 intervertebral disc had small hemorrhages and was friable.

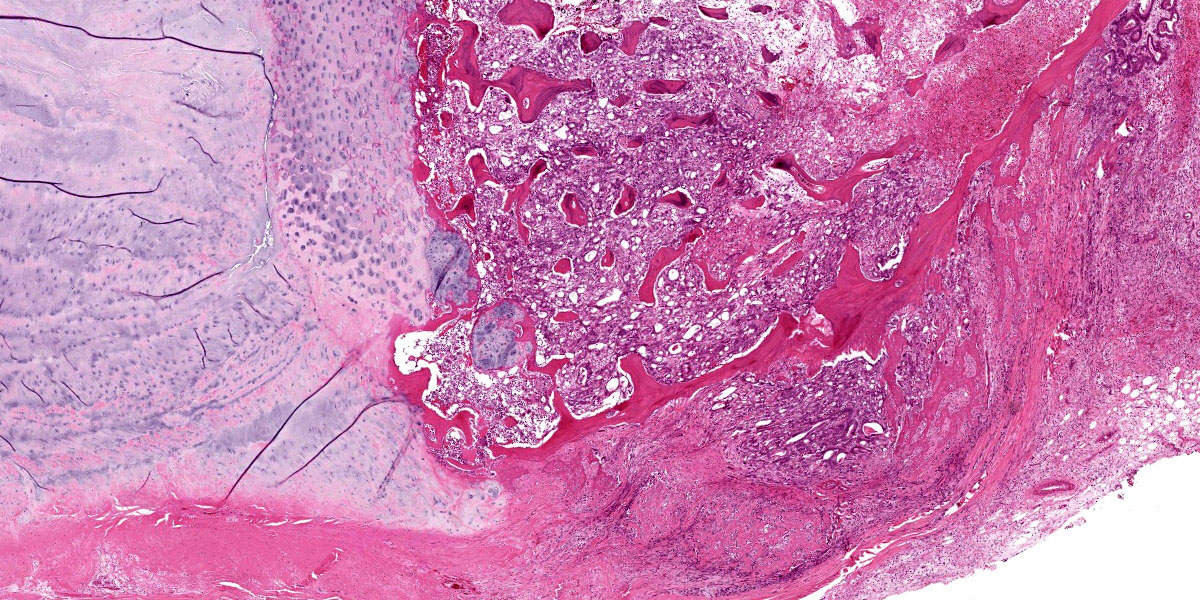

Microscopic Description:

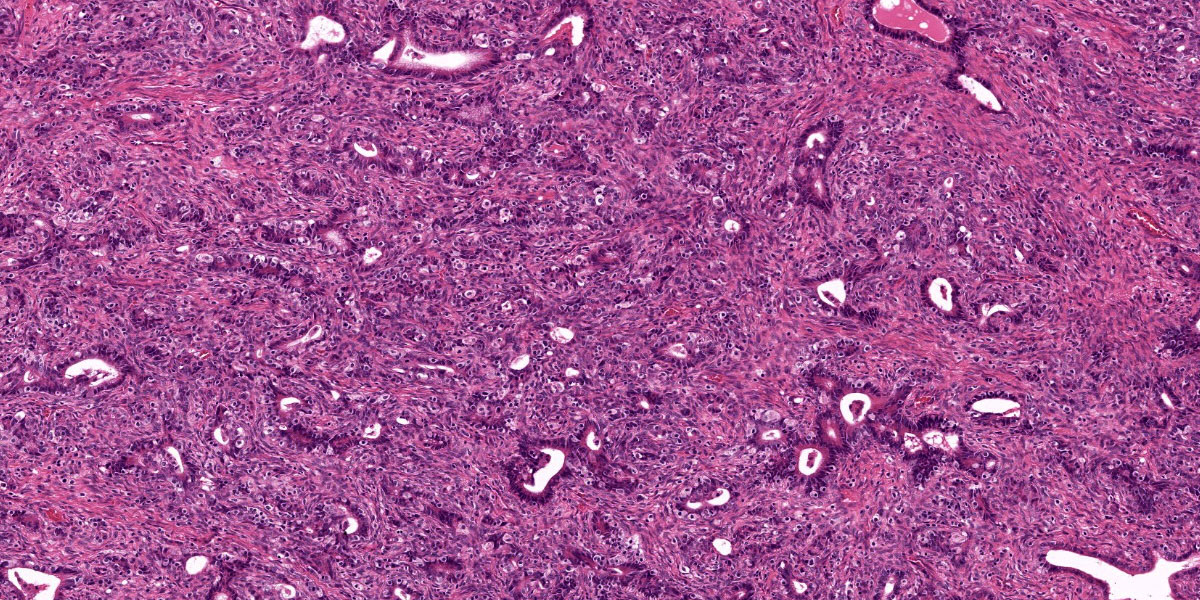

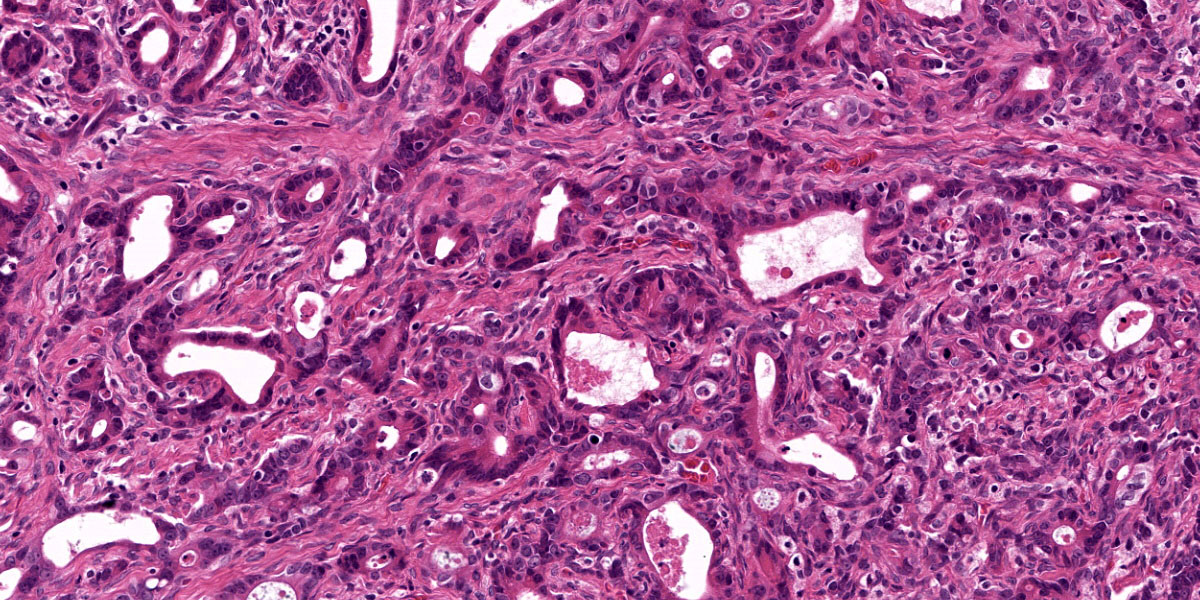

(The submitted slide includes portions of the ovarian tumor, oviduct, uterus, and ventral segment of the vertebral body.) Left ovary: An encapsulated epithelial neoplasm expands and effaces the entire ovary. The neoplastic cells are arranged in streams, nests and acini on a dense, highly cellular fibrovascular stroma. The cells are closely-spaced, and vary from columnar where forming acini, to spindle-shaped when in streams and along the capsule margin. They have eosinophilic cytoplasm and central nuclei with finely-stippled chromatin and single prominent nucleoli. Many cells are multinucleated, with up to four nuclei. Mitotic figures average 1 per 40x field, with rare bizarre forms. The capsule is invaded by neoplastic cells forming single-file rows. Central necrosis is prominent, and many neutrophils and lymphocytes are scattered throughout. Small rafts of neoplastic cells are present within the adhered myometrium, and in the lumina of uterine vessels.

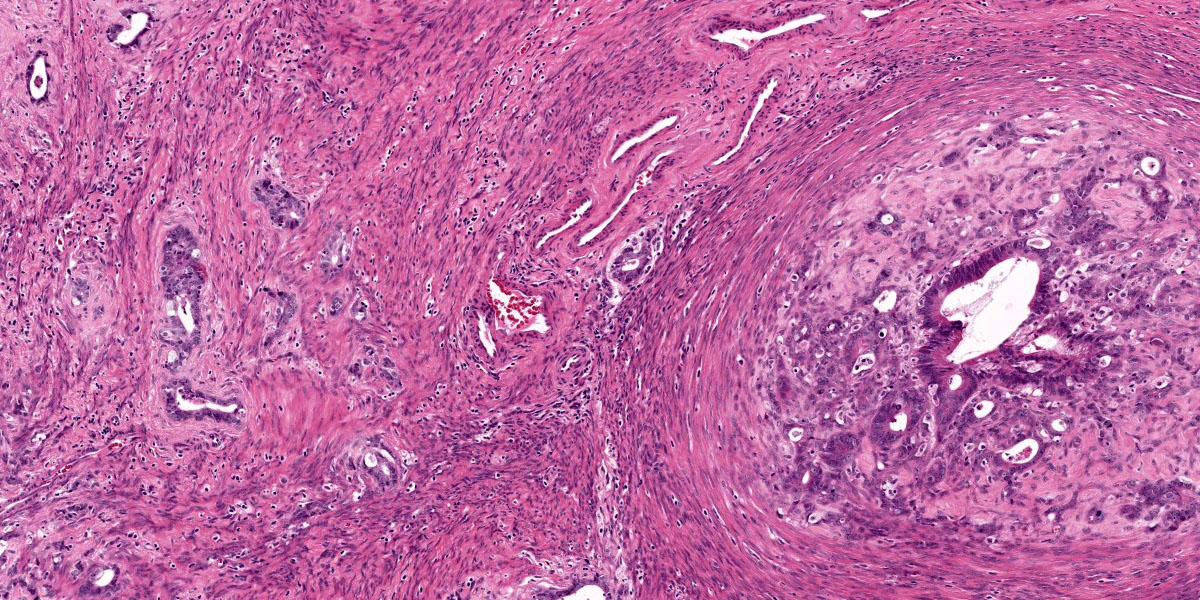

Vertebra – L2: (ventral aspect of the vertebral body): Approximately 70% of the marrow cavity is effaced by neoplastic cells similar to those described for the ovary, interspersed with pale eosinophilic necrotic cellular debris and blood. Neoplastic acini invade into and through the vetebral cortical bone. The neoplastic stroma is less pronounced than that in the ovarian lesion. The remaining bony trabeculae have empty lacunae and are unattended by osteoclasts or osteoblasts (necrosis).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Ovarian carcinoma with vertebral and uterine metastases.

Contributor’s Comment:

In this case, subsequent histopathologic exam revealed a similar smaller neoplasm to that described above in the contralateral ovary. Ovarian carcinoma is a rarely reported neoplasm in this species,7 and domestic animals in general.5 In humans, metastases from the ovary to bone is rare, and in one survey of 1,481 cases of stage IV ovarian carcinoma, only 32 (3.2%) had bone metastases.1 Bilateral carcinomas

are reported in approximately 25% of humans with ovarian cancer,6 and are relatively common in dogs as well.5 The dense mesenchymal component of the primary tumor in this case was striking and the morphology did not fit into the common subtypes of ovarian carcinomas described in domestic animals and humans, IE: papillary, cystic, serous, endometrioid, clear cell or mucinous.5

In humans, differentiating primary ovarian carcinoma from metastatic intestinal carcinoma often proves challenging, as the ovaries are common metastatic sites. Metastatic intestinal carcinomas often histologically mimic ovarian carcinomas in humans, and while identifying the typical features of metastatic neoplasms may prove useful, none are considered highly specific.3 Considering the history of intestinal adenocarcinoma in this animal, ruling-out intestinal adenocarcinoma was salient in this case. At necropsy, the entire intestinal tract was closely examined for evidence of recurrence but no gross or histologic intestinal neoplastic lesions were discovered.

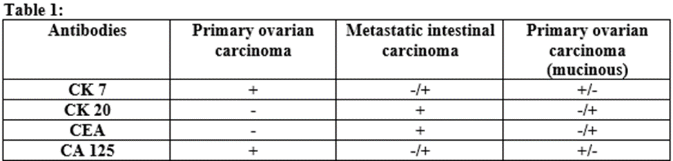

Historically, the immunohistochemical (IHC) panel used to differentiate primary ovarian carcinoma from metastatic intestinal carcinoma included cytokeratin-7, cytokeratin-20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen-125, summarized in Table 1.3 However, more recent studies have shown that tumors with a mucinous subtype further complicate diagnostics.4 The contributors determined that this his particular neoplasm was not mucinous.

Unfortunately the COVID-19 global pandemic precluded the completion of an IHC panel for this case prior to the Wednesday Slide Conference submission deadline, but will be performed at some stage and the results will be submitted.

Contributing Institution:

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Department of Pathology, Section on Comparative Medicine

Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157

www.wakehealth.edu

JPC Diagnoses:

- Ovary, uterus: Adenocarcinoma.

- Vertebral body: Metastatic adenocarcinoma.

JPC Comment:

Dr. Eckhaus noted that in his experience, primary ovarian neoplasms are very rare in non-human primates – in his review of nearly 20,000 cases across almost 40 years at the NIH, he noted 4 total cases of ovarian neoplasia that were all benign (three adenomas and one granulosa cell tumor).

Tissue identification proved to be a bit of a problem for participants, as no normal ovarian tissue was present on the slide, and the orientation of the uterus is somewhat problematic. Intestinal adenocarcinoma, a very common malignancy in rhesus macaques, was favored by many participants given the formation of tubules and acini within the mass. This proved to be an important rule out for this case given this animal’s previous history (which participants were not privy to before the case discussion). We completed the immunohistochemical panel suggested by the contributor in Table 1 with the exception of CA 125 which was not available in our lab. Neoplastic cells demonstrate strong cytoplasmic immunopositivity for AE1/AE3, consistent with an epithelial neoplasm. CEA, CK 7, and CK 20 were all immunonegative, which likely excludes a metastatic intestinal carcinoma. Other potential differentials that we considered are a fimbrial (oviductal) adenocarcinoma and uterine adenocarcinoma given the proximity of these neoplastic cells to the uterus (figure 3-6). Ultimately, as ovary cannot be identified as a primary site on the submitted HE, we prefer a morphologic diagnosis of carcinoma within the ovary to ovarian carcinoma in this case. (We do believe that the contributors correctly identified ovary at necropsy; it is simply the difficult of making this identification on the submitted HE slides which makes us reticent to go “all-in” on this histologic diagnosis as well. Conference participants found the dramatic vertebral changes easier to interpret for this case (figure 3-7).

Although ovarian epithelial neoplasms are rare in NHPs, they are common in human females.8 Metastases to bone are rarely reported in humans, with a prevalence of approximately 1% in a large cohort study of over 32,000 ovarian carcinoma patients.8 The frequency of ovarian neoplasms is companion animals is likely adversely impacted by the common practice of ovariohysterectomy, although malignant epithelial tumors do occur in female dogs. In a recent retrospective, 4 out of 18 dogs with malignant ovarian tumors had metastasis to regional lymph nodes, the lung, and/or the brain – bone is not a common site for metastasis in the dog, either.2

References:

- Deng K, Yang C, Tan Q, et al. Sites of distant metastases and overall survival in ovarian cancer: A study of 1481 patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150: 460-465.

- Goto S, Iwasaki R, Sakai H, Mori T. A retrospective analysis on the outcome of 18 dogs with malignant ovarian tumours. Vet Comp Oncol. 2021; 19: 442–450.

- Kir G, Gurbuz A, Karateke A, Kir M. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical profile of ovarian metastases from colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;2: 109-116.

- Lin X, Lindner JL, Silverman JF, Liu Y. Intestinal type and endocervical-like ovarian mucinous neoplasms are immunophenotypically distinct entities. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2008;16: 453-458.

- Meuten DJ. Tumors in domestic animals, Fifth edition. ed. pp. viii, 989 pages. Ames, Iowa: Wiley/Blackwell; 2017.

- Micci F, Haugom L, Ahlquist T, et al. Tumor spreading to the contralateral ovary in bilateral ovarian carcinoma is a late event in clonal evolution. J Oncol. 2010;2010: 646340.

- Simmons HA, Mattison JA. The incidence of spontaneous neoplasia in two populations of captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14: 221-227.

- Zhang C, Guo X, Peltzer K, et al. The prevalence, associated factors for bone metastases development and prognosis in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer: a large population based real-world study. J Cancer. 2019 Jun 2;10(14):3133-3139.