Conference 15, Case 3:

Signalment:

Adult female wild mouse (Mus musculus)

History:

This wild mouse was found dead in a primate enclosure.

Gross Pathology:

The aorta was lacerated at the level of T8-T9 where the spinal column was severely dislocated and the thoracic cavity contained a large blood clot.

Laboratory Results:

N/A

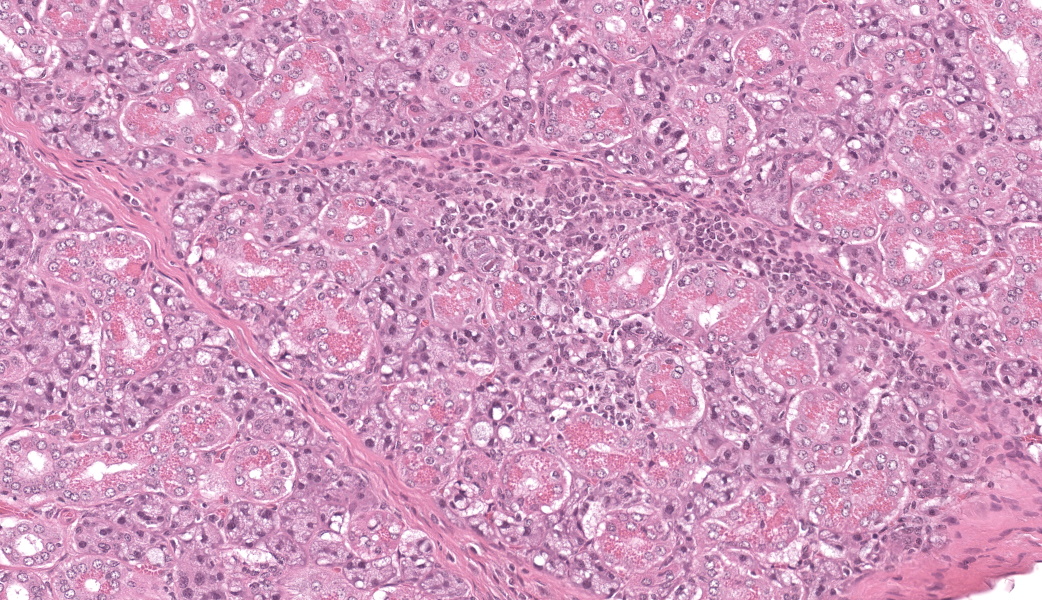

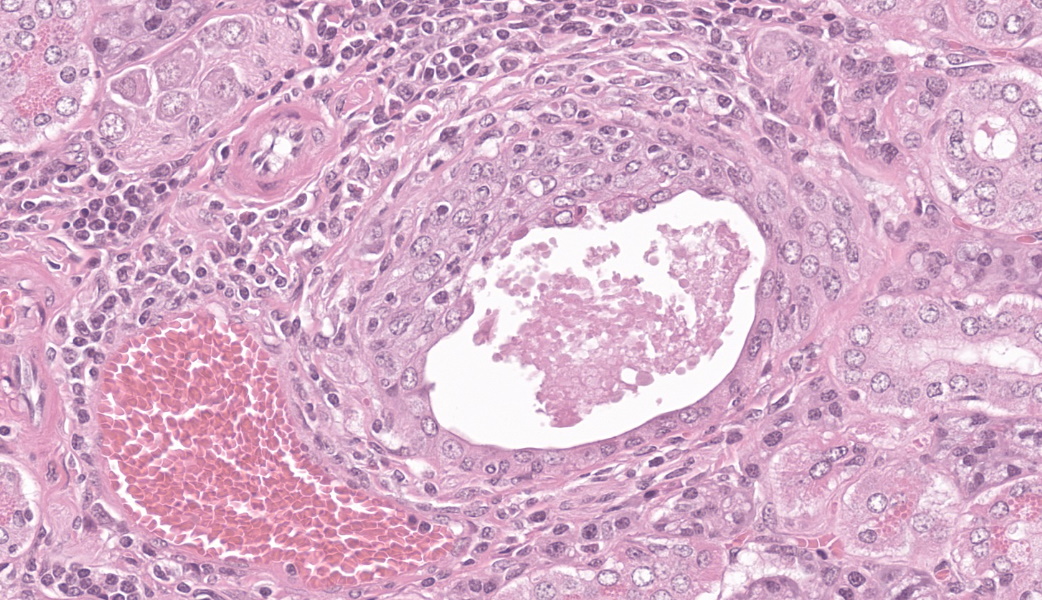

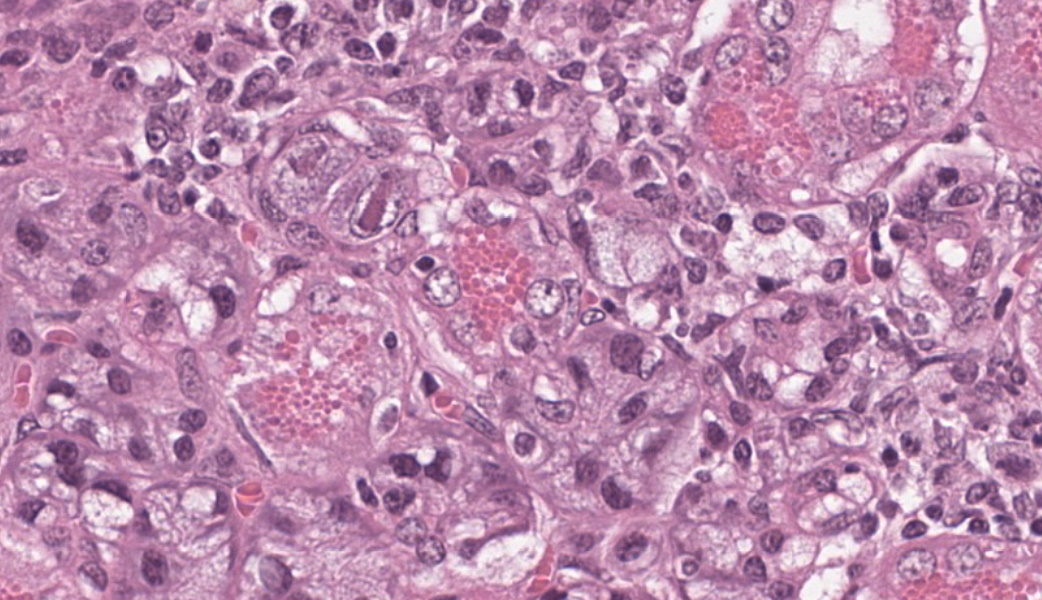

Microscopic Description:

Few acinar and stromal cells with markedly enlarged nuclei and abundant cytoplasm (cytomegaly) with 8-12 µm eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions were scattered throughout the submandibular salivary gland with accompanying lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in several regions.p

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Sialoadenitis, multifocal, subacute to chronic, mild with epithelial and stromal cytomegaly and intranuclear inclusions (cytomegalovirus)p

Contributor’s Comment:

Although traumatic laceration of the thoracic aorta with resultant hemothorax was considered the cause of death, infection with mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) was a prominent incidental finding in this wild mouse. Wild mice are commonly infected with MCMV, a DNA virus in the family Herpesviridae, subfamily Betaherpesvirinae, and genus Muromegalovirus.6 Several genetically distinct strains of MCMV exist within wild mouse populations, and mixed infections of single mice are not uncommon. In fact, up to four genetically distinct strains of MCMV have been isolated from a single wild mouse.3

The most frequently encountered lesions occur in the submandibular salivary glands and rarely in the parotid glands, with excretion in saliva serving as the primary means of transmission through grooming and biting activities. Typical histological findings include eosinophilic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions in acinar epithelial cells with cytomegaly and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation.6 Intranuclear inclusions result from viral DNA replication within the nuclei of infected cells, while intracytoplasmic inclusions represent replication processes that occur in the cytoplasm, including production of the capsid protein.8

As resistance typically evolves after weaning, overt disease and disseminated lesions occur infrequently in naturally infected mice.

Neonates are more susceptible to severe disease which may result in encephalitis, retinitis, pneumonia, hepatitis, myocarditis, adrenalitis and haemopoietic failure. MCMV causes lifelong, persistent infections with intermittent reactivation and viral shedding at times of host immunosuppression. Latent virus in mice may be found in the salivary glands and in other tissues including lung, spleen, liver, kidney, heart, adrenal glands, and myeloid cells.6

The betaherpesviruses are highly host specific. Natural infections of cytomegalovirus occur in primates and guinea pigs as well as mice. Rhesus cytomegalovirus (macacine herpesvirus-3) is the most common opportunistic viral infection in rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus.1 It causes multiorgan dysfunction, with interstitial pneumonia, encephalitis, gastroenteritis and lymphadenitis being most common.2 In guinea pigs, lesions are largely regarded as incidental findings at necropsy and usually confined to the salivary ductal epithelial cells.8

As the course of MCMV infection in mice has similarities to the course of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection, MCMV has been extensively studied and used as a model of the human disease. Credited as the “mother of cytomegalovirus,” M. G. Smith first isolated MCMV from the salivary glands of naturally infected laboratory mice in 1954 and propagated it in cell culture.7 Most laboratory studies have utilized the original Smith strain of MCMV, or derivates thereof, which may not accurately reflect the natural biology of MCMV strains. Nevertheless, the intense scrutiny of MCMV as a model system has shed considerable light on disease pathogenesis.6

Investigations into the variable susceptibility of mouse strains to MCMV infection have shown that innate immune function, in particular the effectiveness of the natural killer (NK) cell response, is the key determinant of resistance to the initial infection and the suppression of viral replication. For example, C57BL/6 (B6) mice are generally considered resistant to MCMV due to the expression of Cmv-1 encoded Ly49H, an NK cell-activating receptor that recognizes the m157 viral protein at the surface of MCMV-infected cells. Activated NK cells suppress the infection by direct lysis of infected cells and by producing cytokines to mediate T-cell responses.4 Other genetically resistant mouse strains include B10, CBA and C3H mice, while susceptible strains include BALB/c and A strain mice. Susceptibility of wild mice to MCMV strains that circulate in wild populations is attributed to m157 proteins that are unable to activate NK cells via Ly49H.9 Humoral immunity is relatively unimportant in controlling MCMV infection.

Contributing Institution:

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Department of Pathology, Section on Comparative Medicine

Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157

www.wakehealth.edu

JPC Diagnoses:

Salivary gland: Sialoadenitis, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, multifocal, mild, with epithelial karyomegaly and intranuclear viral inclusions.

JPC Comment:

This case provided an excellent example of a truly classic lesion that every pathologist should be able to recognize and should come to the forefront of the mind when presented with a slide of murine salivary gland. The contributor provided a great comment on cytomegaloviruses and covered much of what was taught during this case in conference.

The submandibular salivary gland in mice (and multiple other species) is a mixed gland with both serous and mucinous glands. In male mice, the submandibular salivary glands are larger than those in female mice and contain brightly eosinophilic, prominent granules in the ductal epithelial cells. Don’t forget, though, that those granules can also be seen in pregnant females. B6-strain mice are resistant to infection with CMV, but DBA2 and BALB/C mouse strains are susceptible due to their immune bias towards a Th2 (humoral) response. A subdued Th1 (cell-mediated) immune response results in less effective defense against intracellular pathogens, such as viruses. Th2 cells produce cytokines IL-4 and IL-10, which inhibit the development and function of Th1 cells and their key cytokines, which include interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). A strong IFN-γ response is essential for activating cell-mediated immunity and effectively eliminating virus-infected cells.

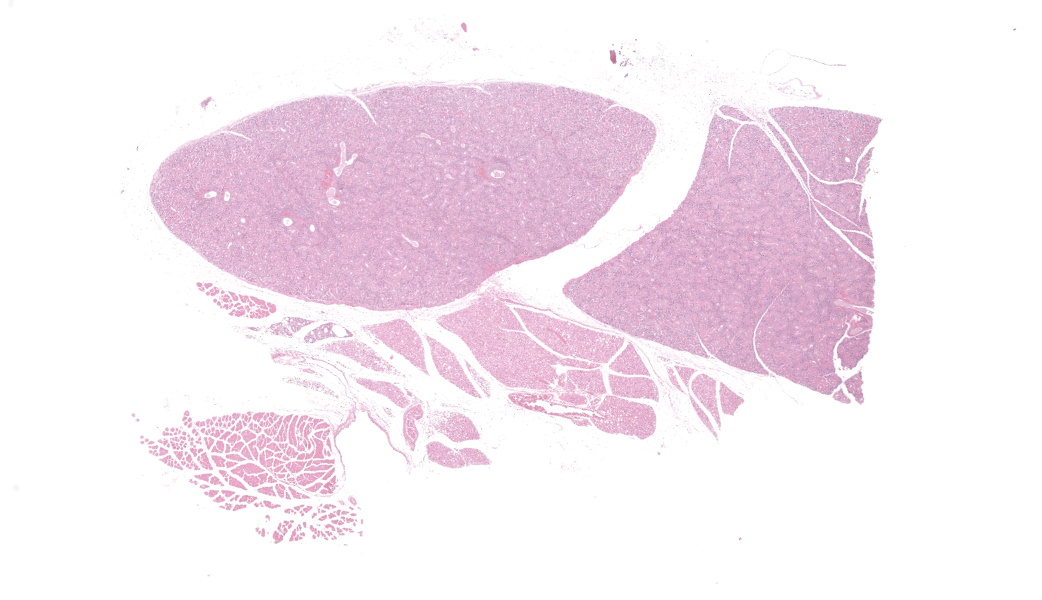

While the tissue identification and diagnosis in this case were straightforward, there were some other structures on the slide that served as an excellent reminder of mouse anatomy. Mammary tissue in mice is extensive and can be as far cranial as the submandibular area. Mammary glands are frequently seen in association with the submandibular salivary gland, often hanging out in the subcutaneous tissues.

Another primary differential for viral inclusions in the salivary glands of mice is murine polyomavirus (MmusPyV-1). This double-stranded DNA virus is, as the name implies, associated with the development of multiple neoplasms in infected mice. While not all polyomaviruses cause neoplasm development, mouse polyomavirus is well-known to do so. Hamster polyomavirus is similar.

One other important betaherpesvirus of note from discussion is suid herpesvirus-2 (porcine roseolovirus), which causes necrotizing rhinitis and abortions in swine and can be lethal to humans.5

References:

- Assaf BT, Knight HL, Miller AD. Rhesus cytomegalovirus (Macacine herpesvirus 3)-associated facial neuritis in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol.2015;52(1):217-223.

- Baskin GB. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection in immunodeficient rhesus monkeys. Am J Pathol. 1987;129(2):345-352.

- Booth M, et al. “Molecular and Biological Characterization of New Strains of Murine Cytomegalovirus Isolated from Wild Mice.” Archives of Virology. 1993:132(1-2);209–220.

- Fodil-Cornu N, et al. “Ly49h-Deficient C57BL/6 Mice: A New Mouse Cytomegalovirus-Susceptible Model Remains Resistant to Unrelated Pathogens Controlled by the NK Gene Complex.” Journal of Immunology. 2008:181(9);6394–6405.

- Hansen S, Menandro ML, Franzo G, et al. Presence of porcine cytomegalovirus, a porcine roseolovirus, in wild boars in Italy and Germany. Arch Virol. 2023;168(2):55.

- Lathbury LJ, et al. “Effect of Host Genotype in Determining the Relative Roles of Natural Killer Cells and T Cells in Mediating Protection against Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection.” Journal of General Virology. 1996:77(10);2605–2613.

- Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:222.

- Reddehase, MJ. “Margaret Gladys Smith, Mother of Cytomegalovirus: 60th Anniversary of Cytomegalovirus Isolation.” Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 2015:204(3);239–241.

- The Joint Pathology Center, Wednesday Slide Conference 2014-2015, Conference 14, Case: 01.” org. 2015.

- Voigt V, et al. “Murine Cytomegalovirus M157 Mutation and Variation Leads to Immune Evasion of Natural Killer Cells.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003:100(23);13483–13488.