Signalment:

Six-month-old, male, Tonkinese cat, (

Felis catus).The cat

presented for further investigation of a vestibular ataxia, head tremors, inappetence,

and lethargy. The cat was in poor body condition compared to its littermate and

had previously been found to be pyrexic. Neurological examination findings

were consistent with a central vestibular syndrome. MRI of the brain revealed

marked dilatation of the third and fourth ventricles and mild dilatation of the

lateral ventricles. There was marked contrast enhancement of the ependymal

lining and meninges, consistent with feline infectious peritonitis and

obstructive hydrocephalus. Cerebellar herniation was present with caudal

displacement of the cerebellar vermis through the foramen magnum, consistent

with elevated intracranial pressure. A provisional diagnosis of feline

infectious peritonitis (FIP) was made. Due to a grave prognosis, the cat was

euthanized and submitted for necropsy examination.

Gross Description:

An increased

volume of clear fluid drained from the cranium as the brain was removed and

there appeared to be diffuse flattening of the cortical gyri. The brain was

dissected following fixation and there was moderate dilation of the third,

fourth and lateral ventricles.

Histopathologic Description:

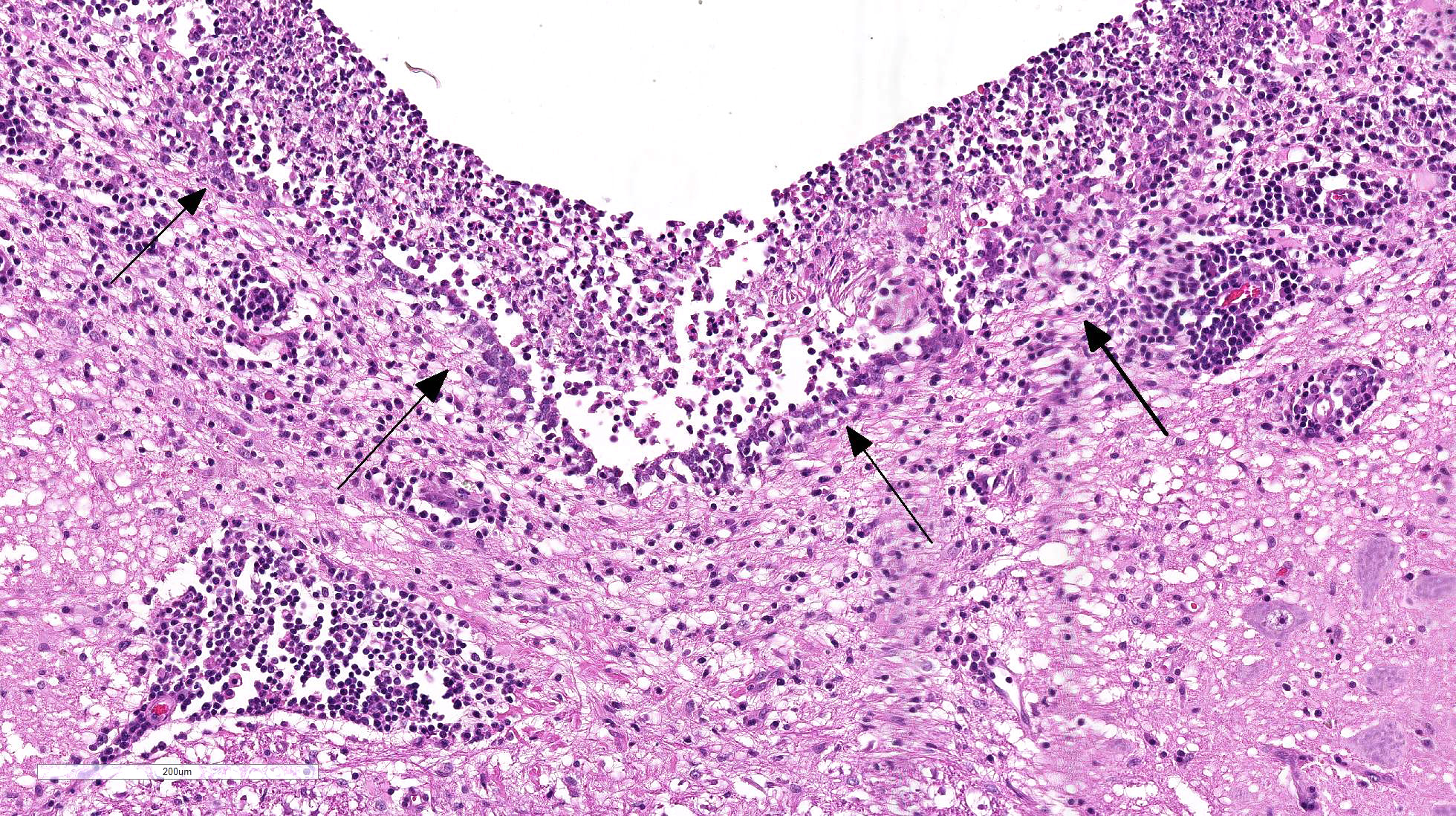

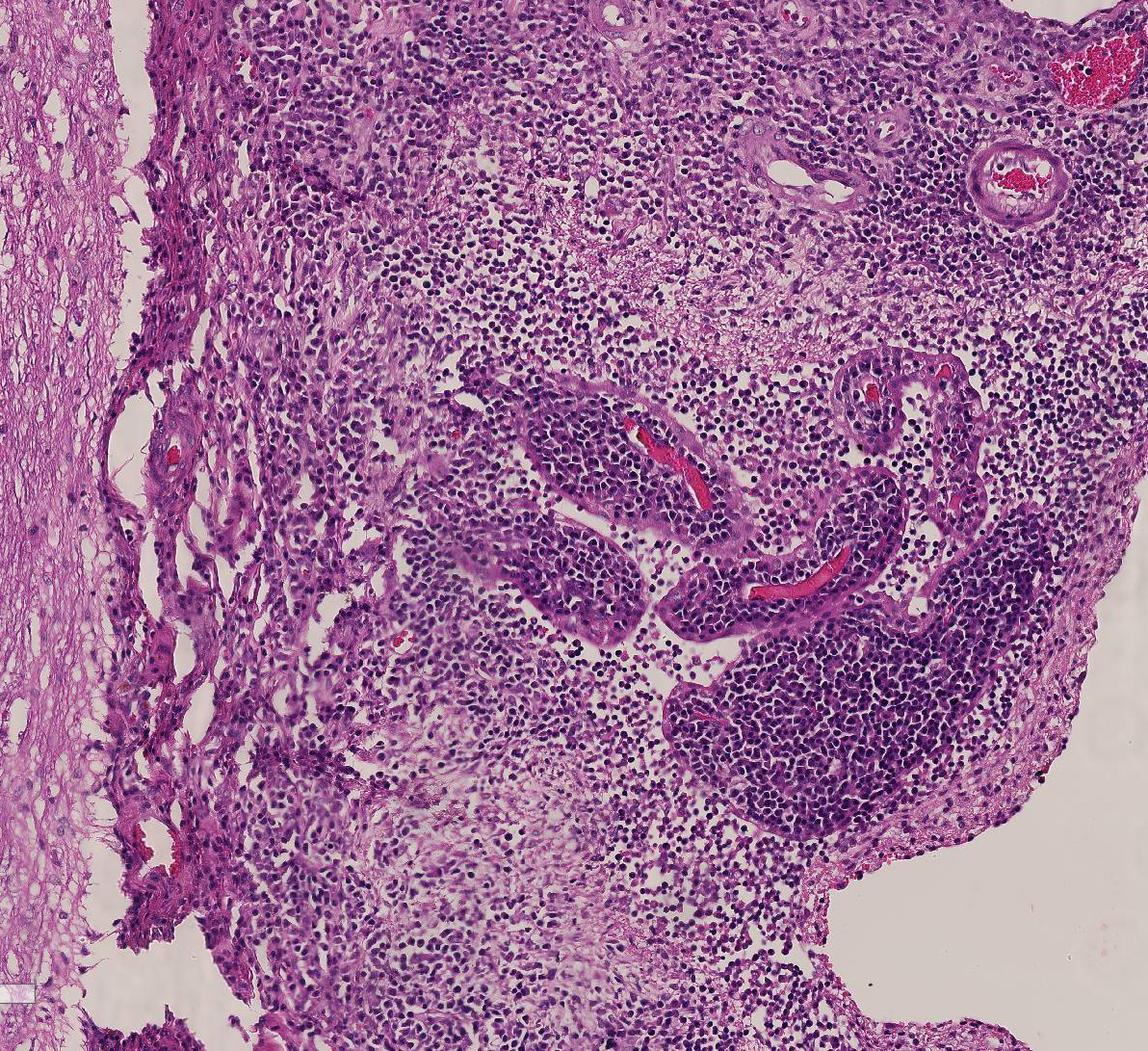

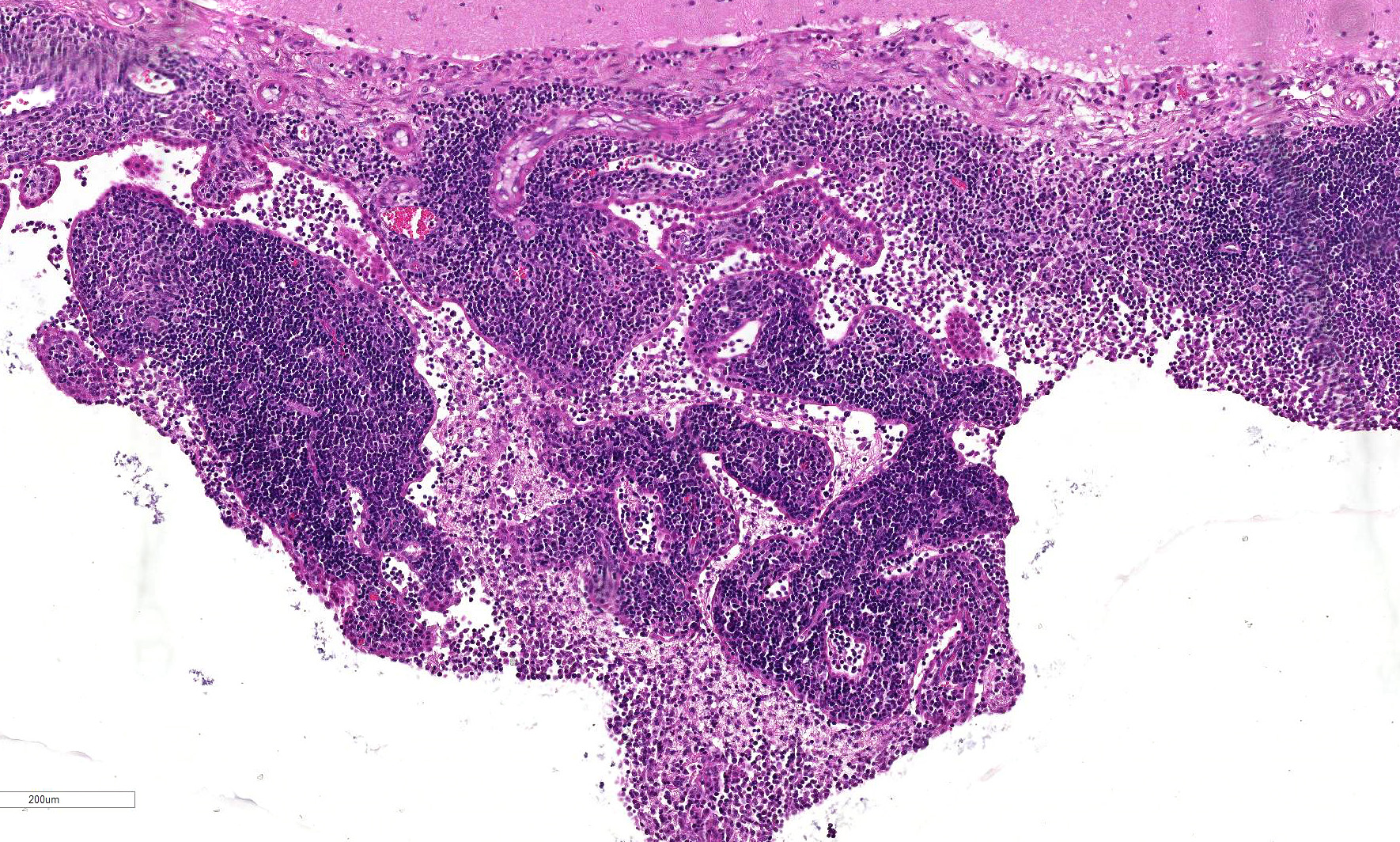

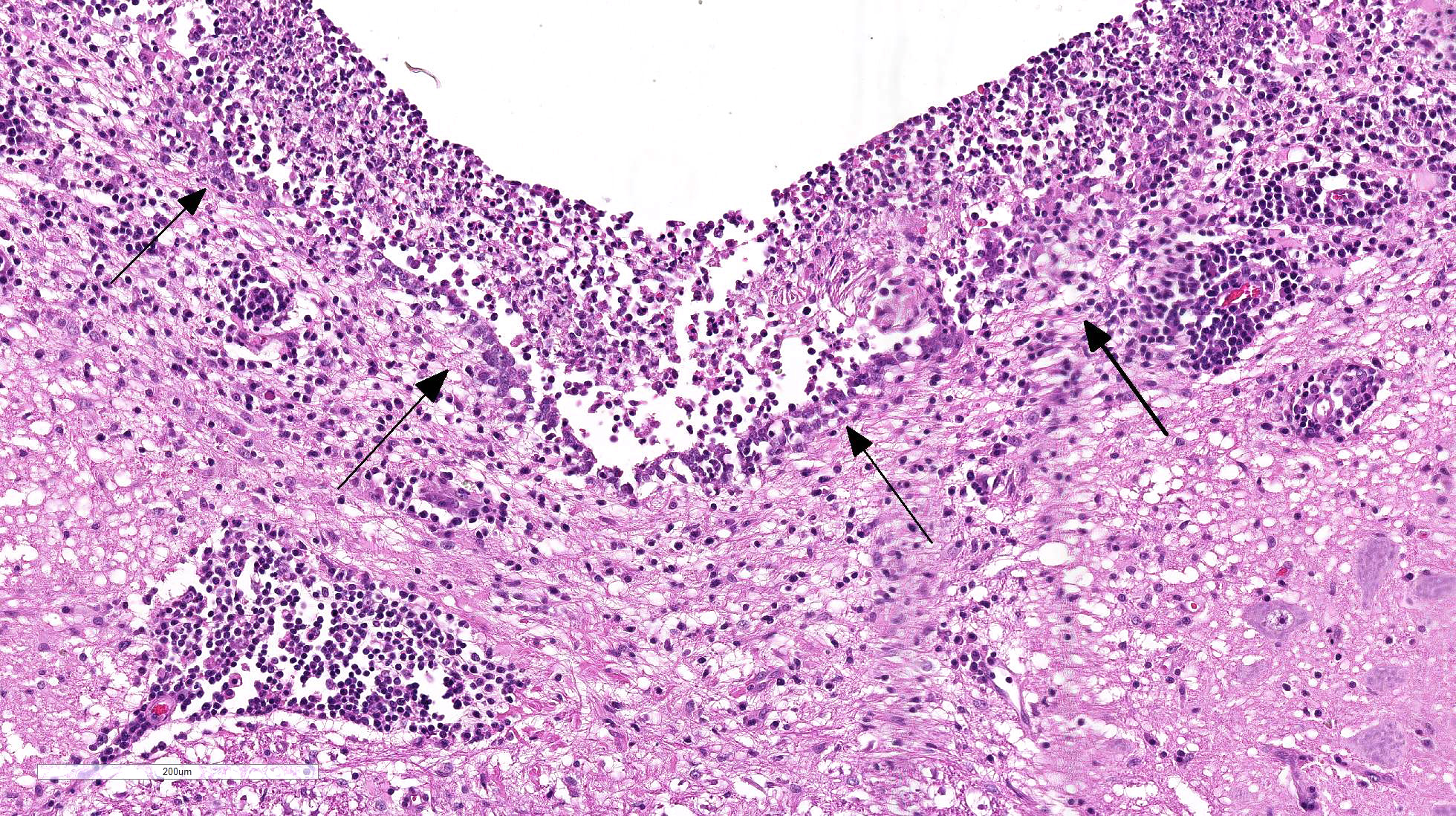

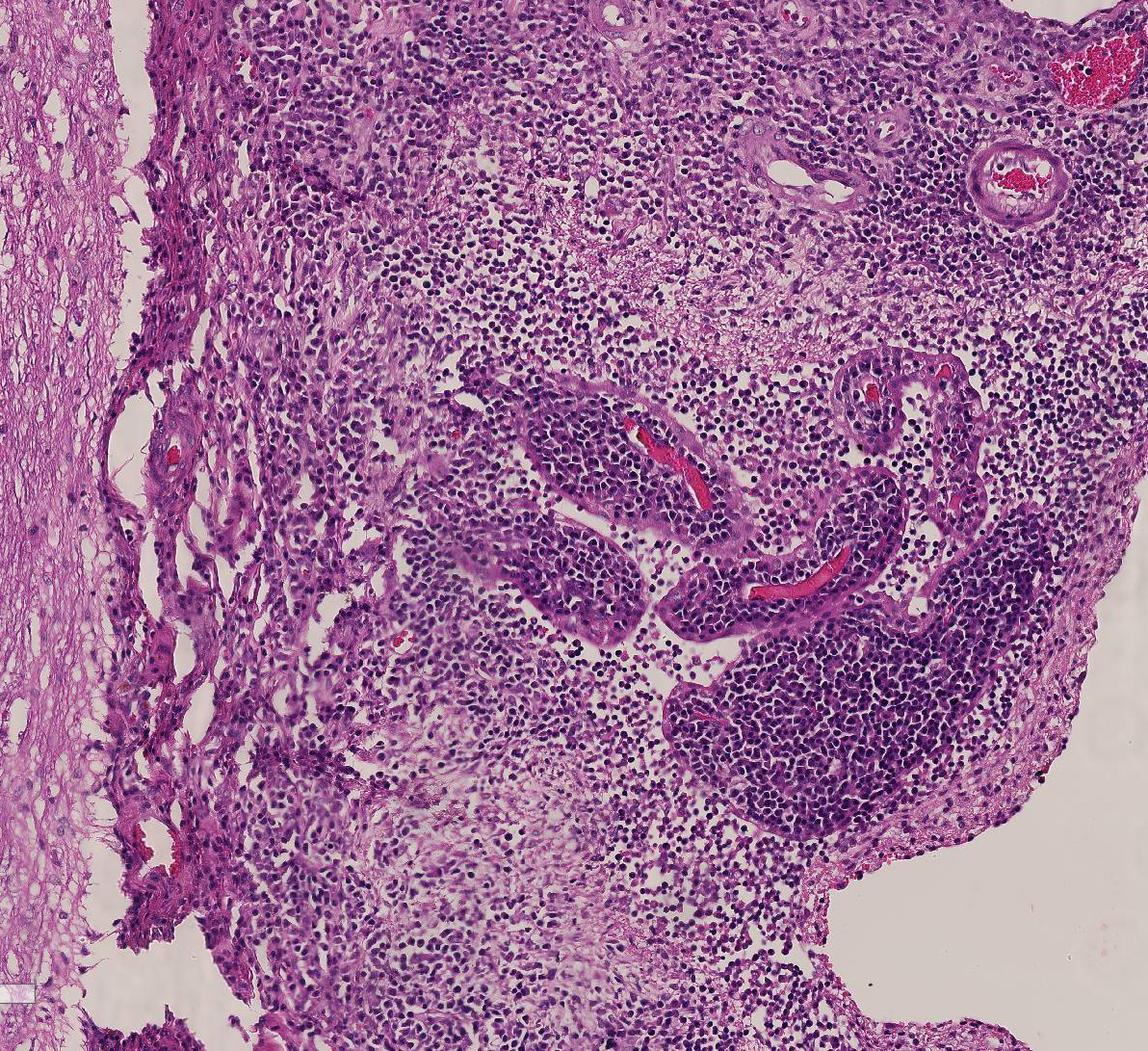

Brain

: Sections of

forebrain, midbrain, cerebellum and brainstem are examined. Variably

within the examined sections the meninges, choroid plexus and ependyma are

multifocally and extensively expanded by dense infiltrates of lymphocytes,

plasma cells, macrophages and rare viable and degenerate neutrophils. There is

prominent perivascular cuffing, predominantly targeting veins, of

periventricular and meningeal blood vessels by lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma

cells and occasional viable and degenerate neutrophils. The inflammatory

infiltrate extends into both vascular walls and beyond the Virchow-Robin spaces

into the adjacent neuropil. There is a mild to

moderate gliosis within the adjacent neuropil and periventricular white

matter contains variably-sized extracellular clear spaces (edema). Ependymal cells lining the ventricles appear

mildly elongate with disruption and increased spacing between cells.

Multifocally, there is necrosis of the ventricular lining with deposition of

fibrin.

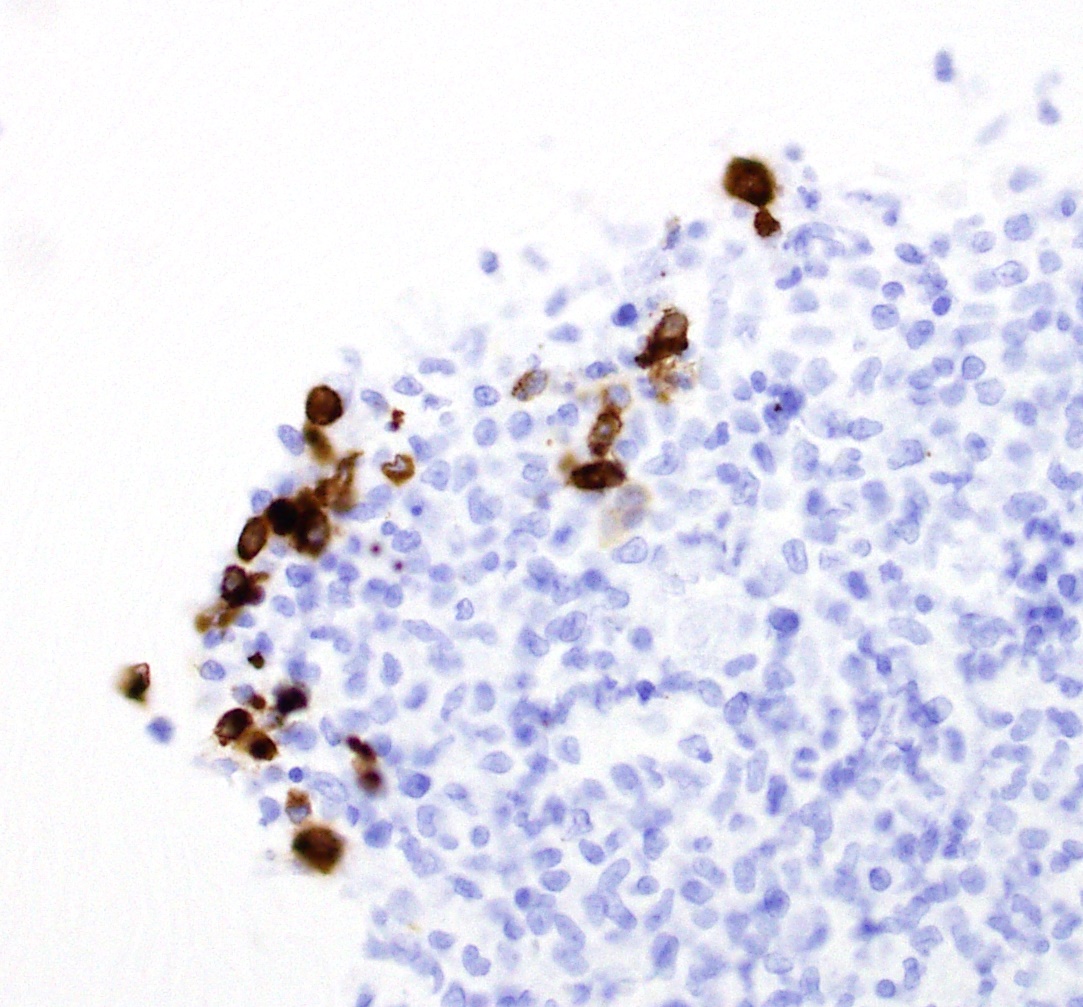

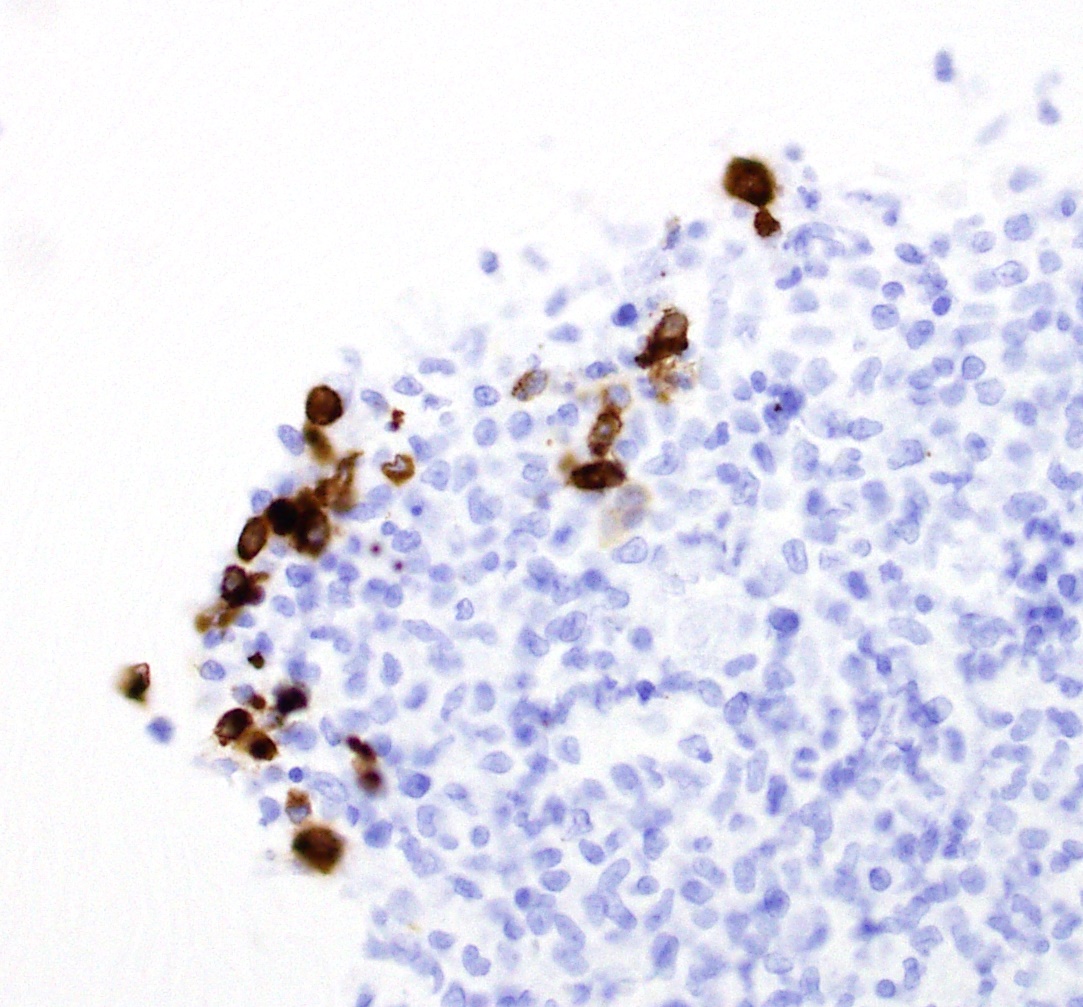

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical

labeling for feline coronavirus antigen identified scattered, large, foamy

round cells (macrophages) which labeled positively for Coronavirus antigen

within the lesions in the brain tissue.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Brain: multifocal, marked, pyo-granulomatous

and lymphoplasmacytic meningoencephalitis with vasculitis and perivasculitis,

ventriculitis, choroiditis and ependymitis

2. Brain:

moderate acquired hydrocephalus

Lab Results:

Feline

coronavirus antibody titer was extremely high; CSF (post mortem) showed a

marked, mixed pleocytosis with neutrophilic predominance and markedly increased

protein con-centration.

Condition:

Pneumonia/Acanthamoeba spp

Contributor Comment:

Feline

corona-viruses (FCoVs) are enveloped,

single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses that belong to the Coronaviridae

family, Alphacoronavirus genus and exist as two pathotypes, feline

infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) and feline enteric coronavirus (FECV).1,3

Despite FCoVs being ubiquitous in the environment, with a prevalence of more

than 90% of cats in multicat households, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is

sporadic, with young, entire male, purebreed cats most commonly affected1.

Feline enteric coronavirus is generally considered avirulent, however, can be

associated with hemorrhagic enteritis and diarrhoea and affected cats may become persistently infected and continue to shed virus.

In contrast, FIPV results in severe, systemic disease and is a common cause of

neurologic disorders in young cats. Feline

coronavirus is generally transmitted via the fecal-oral route following which

it infects enterocytes, eventually being restricted to the caecum and colon.1

Analysis of

FECVs and FIPVs suggests a complex scenario involving several gene mutations to

result in increased virulence1,3. Feline

infectious peritonitis viruses appear to have an increased ability to replicate

in macrophages and monocytes and result in systemic disease.1

Virus-infected

macro-phages localize to small and medium sized veins within the serosa and

damage endothelial cells with the subsequent immune response resulting in a

vasculitis. A strong cell-mediated response is protective against FIP, whereas

a weak cell-mediated response results in the dry form of the disease. The

wet form of disease results from a lack of cell-mediated immune response to

the virus. Both type III and type IV hypersensitivity responses have been

implicated in the pathogenesis of FIP.5

Feline

infectious peritonitis is often distinguished by a wet or effusive form and a

dry non-effusive form with a proportion of cases showing a combination of the

two. Typical gross findings associated with the effusive form of FIP include a

fibrinous and granulomatous peritonitis, protein rich effusions and visceral

granulomatous inflammatory foci. In 60% of non-effusive cases of FIP there is

involvement of the eyes and/or CNS with or without granulomatous lesions in the

thoracic and abdominal viscera and frequently in the absence of a grossly

apparent peritonitis2. Gross lesions

in the brain are often unapparent, however may include thickening and opacity

of the meninges, and an obstructive hydrocephalus, as seen in this case.

Proteinaceous material within the ventricular system may be visible as

grey-blue gelatinous material.4

Clinical signs

associated with FIP are often vague and include pyrexia, lethargy and

inappetence with additional changes dependent on the distribution of tissues

affected.2

The

characteristic microscopic findings associated with FIP include a vasculitis

and perivasculitis, predominantly affecting small to medium sized venules. A high

proportion of macrophages alongside variable numbers of neutrophils,

lymphocytes and plasma cells infiltrate and surround vessels. Vascular necrosis

with thrombosis and infarction may also occur.2

Feline

infectious peritonitis may be suspected based on the signalment, compatible

clinical signs, and identification of pathognomonic gross and histologic

lesions. Identification of viral antigen in lesions using immuno-histochemistry

or real time RT-PCR is confirmatory for a diagnosis of FIP.3

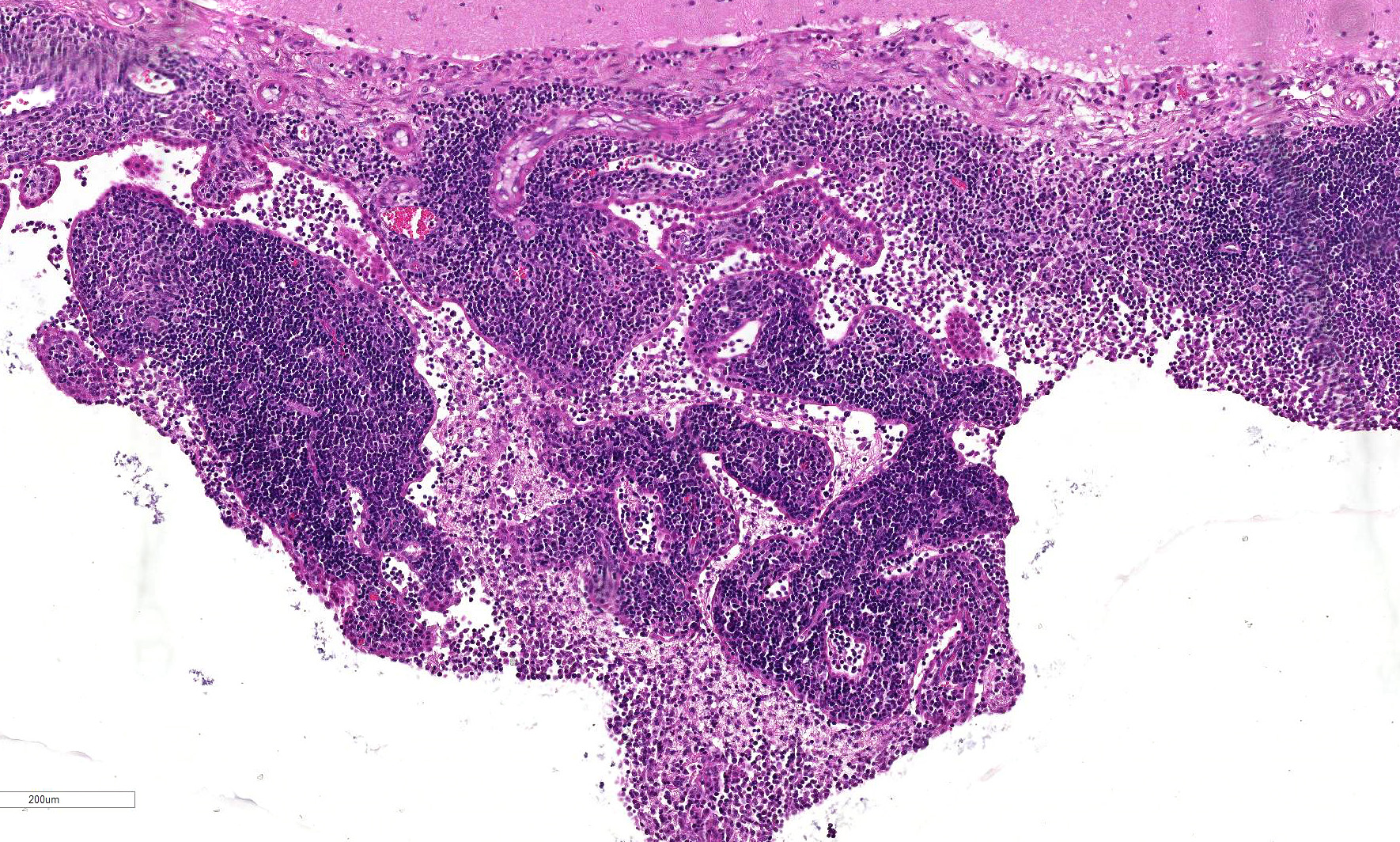

JPC Diagnosis:

Cerebrum,

brainstem: Meningoencephalitis, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic,

perivascular, diffuse, moderate to marked with lympho-plasmacytic and

histiocytic choroiditis and phlebitis, Tonkinese cat, Felis

catus.

Conference Comment:

Although there is some moderate slide variability, we thank the contributor for providing an excellent example and review of

feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a disease that is caused by a mutated

feline enteric coronavirus (mutated FCoV). Given the history provided by the

contributor, this case is likely more consistent with the non-effusive form of

FIP with lesions restricted to the central nervous system, although the

distinction between the wet and dry form is somewhat arbitrary and the disease

likely represents a continuum rather than two distinct clinical forms.3

As mentioned by the contributor, neurologic signs due to encephalitis or

meningitis are present in approximately 60% of all FIP cases.4,5

Chronic ventriculitis, choroiditis, and ependymitis causes outflow obstruction

of the cerebrospinal fluid from the ventricular system of the brain leading to

marked dilation of the ventricles.5 This dilation of the ventricles

leads to a compression atrophy of the proximate neuroparenchyma because of the

lack of expansibility within the skull. The resulting increased intracranial

pressure then results in both hydrocephalus and caudal displacement and

herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum, present in this case.

FIP remains as one of the most common causes of infectious death in cats with

Bengals, Birmans, Himalayans, ragdolls, and Rexes significantly overrepresented

for the development of the disease.3

A recent publication in Veterinary Pathology

by Kiper and Meli1 outlined three key features as prerequisites for

the development of FIP: a) systemic infection with virulent mutated FCoV, b)

effective viral replication in circulating monocytes, and c) activation of

mutated FCoV-infected monocytes.1 Although avirulent FCoV is

readily transmitted via the fecal-oral route, most believe that the mutated

virulent form is not transmitted horizontally, but is rather the result of

spontaneous mutation within each cat that develops FIP. The hallmark lesion of

FIP is granulomatous or lymphohistiocytic phlebitis, present in this case,

which is mediated by activated circulating monocytes during viremia.

Activated monocytes upregulate adhesion molecules

such as CD18, and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1b,

GM-CSF, and IL-6, in addition to matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-9), and

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Endothelial cells appear to be

selectively responsive and activated by the cytokine storm generated, which

limits the distribution of lesions to veins within select organs. The trigger

for the massive monocyte activation and selectivity of lesion location is not

currently known.1

Conference participants discussed the nature of the immune

response by the host as a determining factor for which form of the disease the

animal will have. As mentioned by the contributor, mutated FCoV-infected

circulating monocytes are likely responsible for viremia. The conference

moderator instructed that cats with a strong cell-mediated immune (CMI)

response do not develop FIP.1,3,5 Alternative, a weak CMI and strong

humoral response results in the effusive, or wet form of the disease. This form

is characterized by vasculitis, peritonitis and profound thoracic and

peritoneal effusion as a result of deposition of antigen-antibody complexes

(type III hypersensitivity).3,5 In addition, these cats are

hypergammaglobulinemic due to the overproduction of ineffective antibodies. In

contrast, the noneffusive dry form of the disease is associated with a moderate

CMI response with pyogranulomatous inflammation (type IV hypersensitivity) and

develop clinical signs based on the organs affected, such as the brain in this

case. However, as noted above, the different forms represent a continuum

and most cases are likely a mix of the two extreme forms of the disease. 1,3,5

References:

1. Kipar A, Meli

ML. Feline infectious peritonitis: still an enigma? Vet Pathol. 2014;

51(2):505-526.

2. Pedersen NC: A

review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: 1963-2008. J Feline

Med Surg. 2009; 11(4):225-258.

3. Uzal FA,

Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb,

Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th

ed. Missouri: Elsevier; 2016:253-254.

4. Vandevelde M,

Higgins RJ, Oevermann A. Veterinary Neuro-pathology: Essentials of Theory

and Practice. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

5. Zachary J,

McGavin M. Nervous system. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th

ed. Missouri: Elsevier; 2012:860-861.

Click the slide to view.

2-1 Cat, fourth ventricle.

2-2. Cat, fourth ventricle and underlying brainstem.

2-3. Cat, brainstem meninges:

2-4. Cat, choroid plexus, fourth ventricle.

2-5. Cat, fourth ventricle: