Signalment:

Gross Description:

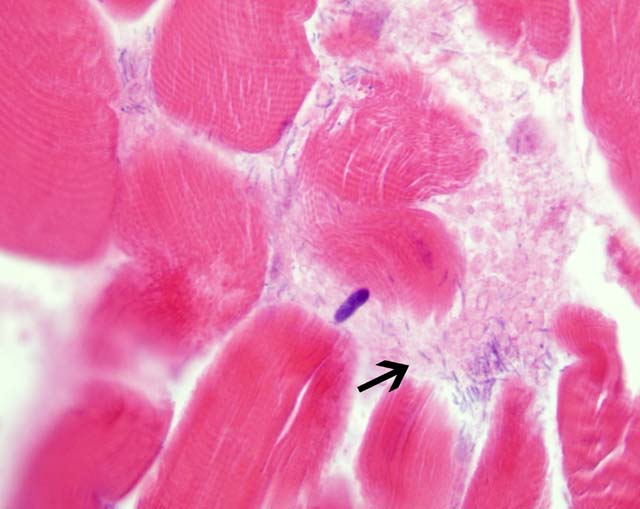

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

This case was submitted because this condition is not commonly seen anymore due to better herd management practices and good vaccines being available and in use in most cattle operations.Â

However, in the Southwestern United States, we do see blackleg occasionally due to some management issues that are unique to our geography and climate. In a desert environment, large acreages are required to range (i.e., pasture) cattle; yearling cattle such as these would require a minimum of 40-60 acres per animal, depending upon availability of forage, drought, etc. Requirements for cow/calf pairs commonly range from 60-100 acres per animal; hence, a 200 cow herd would require 12,000-20,000 acres (20-30 sections). Many operations leave the bulls out with the cows all year, thus having year round calving and calves of many different sizes and weights. Thus, these large ranges (often in very rugged and inaccessible country, except by horseback) make doing a gather for any reason difficult, very labor intensive, time consuming, and requires experienced and savvy cowboys. As a result, cattle are often only gathered up once a year, usually to select and market heavier calves. Obviously, with these types of management problems, installation of a comprehensive herd health (including vaccinations) program is often a hit-and-miss proposition, as was the case with these animals. This particular animal had not been vaccinated (nor had any of the others).Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Differentiating blackleg from pseudo-blackleg, gas gangrene and malignant edema has important management implications. Pseudo-blackleg is caused by the activation of latent spores of C. septicum in the muscle. C. septicum proliferates rapidly after death, unlike C. chauvoei, so the carcass must be examined immediately after death. Pseudo-blackleg lesions are often multiple and are much less emphysematous. C. septicum also causes hemorrhagic abomasitis (Braxy) in ruminants.(3) Blackleg results from activation of latent spores in muscle, whereas gas gangrene and malignant edema results from contamination of an open wound.(3) Gas gangrene and malignant edema can be caused by a single or mixed infection of C. chauvoei, C. septicum, C. perfringens and C. novyi. The most common cause of malignant edema is C. septicum. Ruminants, horses and swine are most susceptible.(3) Malignant edema causes primarily a cellulitis, rather than a myositis as in gas gangrene. Also, the gas characteristic of gas gangrene is not a feature of malignant edema.(3) C. novyi also causes swelled head in rams, resulting from the infected head wounds received during fighting.(3) C. novyi is also the cause of necrotic hepatitis (Black disease) in sheep, and C. haemolyticum causes bacillary hemoglobinuria in cattle and sheep. In both diseases, clostridial spores are ingested, cross the intestinal mucosam, and remain latent within Kupffer cells. Migrating larvae of the common liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica, cause necrosis which leads to activation of the latent clostridial spores. The spores release beta toxin, a necrotizing and hemolytic lecithinase (phospholipase C), that causes necrosis of the surrounding tissue and hemolysis in bacillary hemoglobinuria. Grossly, there are large pale areas of necrosis surrounded by broad zones of hyperemia. The necrotic area in bacillary hemoglobinuria is usually focal and larger than in Black disease. Bacillary hemoglobinuria causes intravascular hemolysis with anemia and hemoglobinuria.(2)

References:

2. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 355-356. Saunders Elsevier, London, UK, 2007

3. Van Vleet JF, Valentine BA: Muscle and tendon. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 259-264. Saunders Elsevier, London, UK, 2007