Signalment:

Treated with IV fluids, antibiotics and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Deer died within 5 hours.

Gross Description:

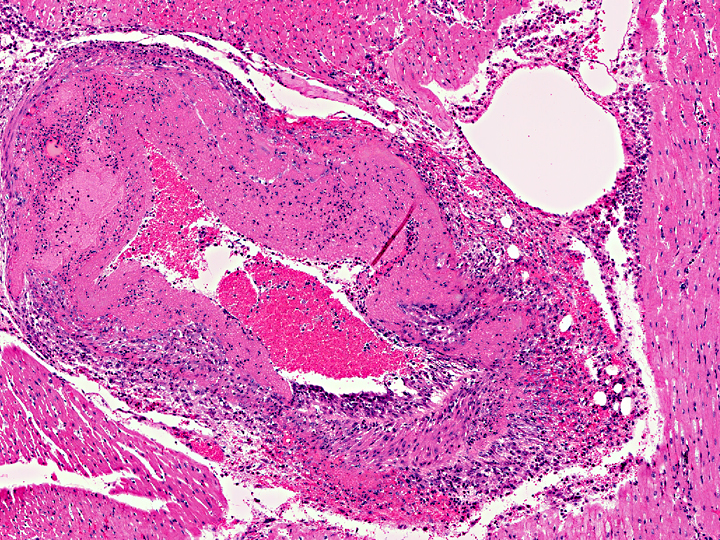

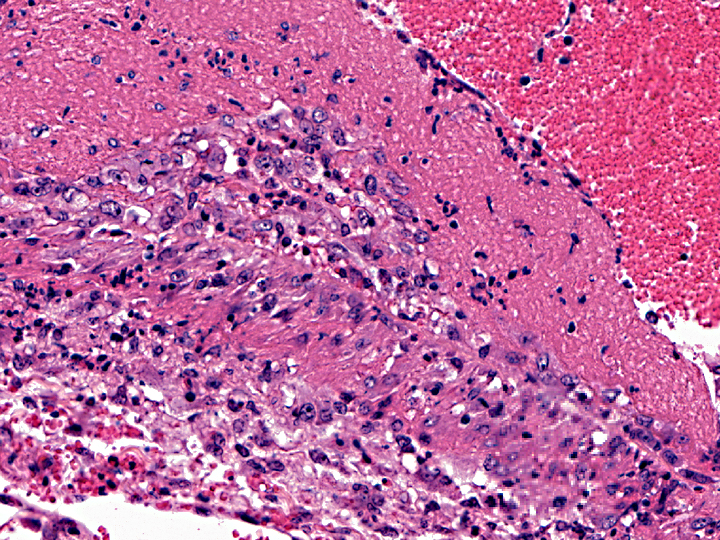

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

PCR for OvHV-2: positive

PCR for EHV: negative

PCR for Bluetongue virus: negative

PCR for BVD: negative

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

An MCF virus of unknown origin that causes clinical disease in white-tailed deer(8), and an MCF virus endemic in goats, provisionally known as caprine herpesvirus-2 (CpHV-2) that has been associated with chronic alopecia in sika and white-tailed deer(5, 6). The literature on MCF contains descriptions of various manifestations of disease with diverse organ involvement. The variable nature of disease expression is thought to result from multiple regulatory genes in gammaherpesviruses acquired during evolution. Cell type as well as host species may alter the expression of these genes(6).

Deer infected with OvHV-2 can have a variety of clinical signs. Typically the affected animal is lethargic, febrile with diarrhea that is often watery or contains blood. Death usually occurs within 48 hours. Animals that live longer may have excessive watery to mucous discharge from the eyes, mouth and nose. Mucosal erosions or ulceration may be present in the nose, oral cavity or anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Corneal opacity may lead to blindness in one or both eyes. Compared to cattle, MCF in deer is usually an acute disease with animals showing few clinical signs before death. Lesions are more hemorrhagic, and involve the viscera of the gastrointestinal tract. MCF in cattle is less acute and the severity of visceral lesions is decreased. Clinical signs in cattle are variable. Grossly, MCF in cattle produces enlarged lymph nodes, corneal edema, cutaneous crusts and hyperemia, oral hyperemia and ulceration, mucopurulent nasal discharge, and erosive or ulcerative lesions throughout the digestive system.

Deer acquire the infection through direct or indirect contact with the reservoir species, most commonly sheep. Reservoir species remain infected with the virus but do not show any clinical signs. Research suggests that deer with MCF do not transmit the virus to other deer. Sheep between the ages of 6 and 9 months of age shed much more virus than do sheep of other ages and therefore are considered most dangerous to deer and other susceptible species(9, 10). Nasal secretions are the predominant vehicle by which virus is spread from sheep to other species(9, 10). There is some evidence that MCF viruses may be spread by aerosol over significant distances. Research on MCF in bison has documented transmission over distances of 2.5 to 3 miles, against prevailing winds and in the absence of common water sources suggesting that some mechanisms of transmission remain undefined.

Recent research suggests that some susceptible species may be latently infected with virus and that there may be recrudescence of disease during periods of stress. Much remains unknown concerning latent infections in susceptible species. The incubation period (time from infection to the manifestation of clinical disease) is unclear and can be quite variable, ranging from a few days to several months. In some species clinical signs have been seen as late as 8 months after exposure to infected sheep. In the present case deer were housed on a pasture that was within 50 yards of a pasture containing sheep. Lambing had occurred on the pasture approximately 6 months earlier. Six month-old lambs were still present on the sheep pasture.

Differential diagnosis for diseases that cause ulceration and necrosis of the oral and gastrointestinal mucosa and hemorrhage in deer and other ruminants include epizootic hemorrhagic disease in deer, bluetongue, bovine virus diarrhea-mucosal disease, rinderpest, and vesicular diseases. Important vesicular diseases to consider are foot and mouth disease and vesicular stomatitis, which are grossly indistinguishable from one another.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The most common sites for vascular lesions are the brain and leptomeninges, carotid rete, kidney, liver, adrenal capsule and medulla, salivary gland, and any section of skin or alimentary tract with gross lesions. Lymphocytic infiltrates are also present in the kidneys, periportal areas of the liver, gastrointestinal mucosa, dermis, meninges, and heart. Microscopic lesions seen in other areas are an active proliferation of lymphoblasts in lymph nodes, especially in T cell-dependent areas of interfollicular and paracortical zones; and lymphocytic uveitis with exudate from ciliary processes into the filtration angle, resulting in corneal opacity of the eye(3, 12, 17).

In MCF, the virus is usually associated with lymphocytes in adults, and primary viral replication occurs in small and medium-sized lymphocytes. T-lymphocyte proliferation is likely secondary to infection of large granular lymphocytes, which have T-suppressor cell and natural killer cell activity. Viral infection and dysfunction of these cells causes lymphoproliferation, T-suppressor cell dysfunction, and necrosis. Thevasculitis is presumed to be immune-mediated, but demonstration of immunoglobulin and complement components has been inconsistent(16).

References:

2. Brown CC, Bloss LL: An epizootic of malignant catarrhal fever in a large captive herd of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Wildl Dis 28(2):301-305, 1992

3. Gelberg HB. Alimentary system and the peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, and peritoneal cavity. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:1078, 1118.

4. Jessup DA: Malignant catarrhal fever in a free-ranging black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus) in California. J Wildl Dis 21(2):167-169, 1985

5. Keel MK, Patterson JG, Noon TH, Bradley GA, Collins JK: Caprine herpesvirus-2 association with naturally occuring malignant catarrhal fever in captive sika deer (Cervus nippon). J Vet Diagn Invest 15:179-183, 2003

6. Li H, Wunschmann A, Keller J, Hall DG, Crawford TB: Caprine hepesvirus-2-associated malignant catarrhal fever in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Vet Diagn Invest 15:46-49, 2003

7. Li H, Westover WC, Crawford TB: Sheep-associated malignant catarrhal fever in a petting zoo. J Zoo Wildl Med 30(3);408-412, 1999

8. Li H, Dyer N, Keller J, Crawford T: Newly recognized herpesvirus causing malignant catarrhal fever in whitetailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Clin Micro 38(4):1313-1318, 2000

9. Li H, Taus NS, Lewis GS, Kim O, Traul DL, Crawford TB: Shedding of ovine herpsesvirus 2 in sheep nasal secretions: the predominant mode for transmission. J Clin Microbiol 42(12):5558-5564, 2004

10. Li H, Hua Y, Snowder G, Crawford TB: Levels of ovine herpesvirus 2 DNA in nasal secretions and blood of sheep: implications for transmission. Vet Microbiol 79:301-310, 2001

11. Maxie MG, Robinson WF. The cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers pathology of domestic animals. 5th ed, vol. 3, New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:72-3.

12. Njaa BL, Wilcock BP. The ear and eye. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:1078, 1118.

13 Reid HW, Buxton D, McKelvey WA, Milne JA, Appleyard WT: Malignant catarrhal fever in Pere Davids deer. Vet Rec 121(12):276-277, 1987

14. Tomkins NW, Jonsson NN, Young MP, Gordon An, McColl KA: An outbreak of malignant catarrhal fever in young rusa deer (Cervus timorensis). Aust Vet J 75(10):722-723, 1997

15. Williams ES, Thorne ET, Dawson HA: Malignant catarrhal fever in a Shiras moos (Alces alces shirasi Nelson). J Wildl Dis 20(3):230-232, 1984

16. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infection. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:219.

17. Zachary JF. Nervous system. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:1078, 1118.