WSC 2022-2023

Conference 21

Case 3

Signalment:

8-week-old, male intact, Australian Heeler dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

This puppy presented with seizures and was euthanized on the same day. The puppy was unvaccinated, and the vaccination status of the dam was unknown.

Gross Pathology:

Unremarkable

Laboratory Results:

|

Sample |

Test |

Results |

|

Brain (unfixed) |

Direct fluorescent antibody testing for rabies virus |

Negative |

|

Lung (unfixed) |

Aerobic culture |

No growth |

Microscopic Description:

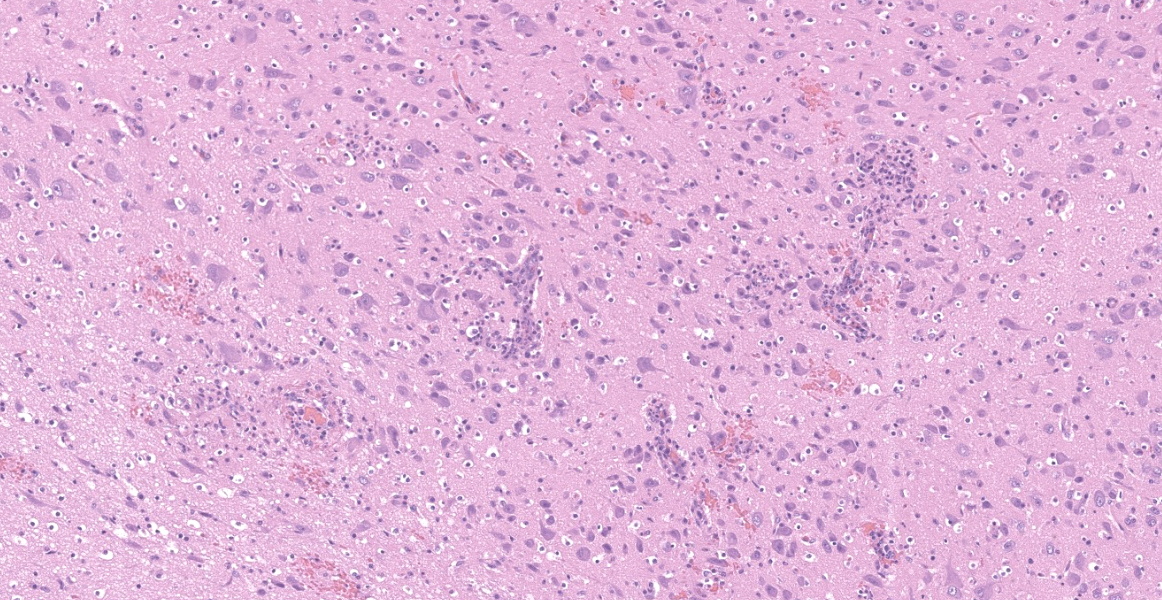

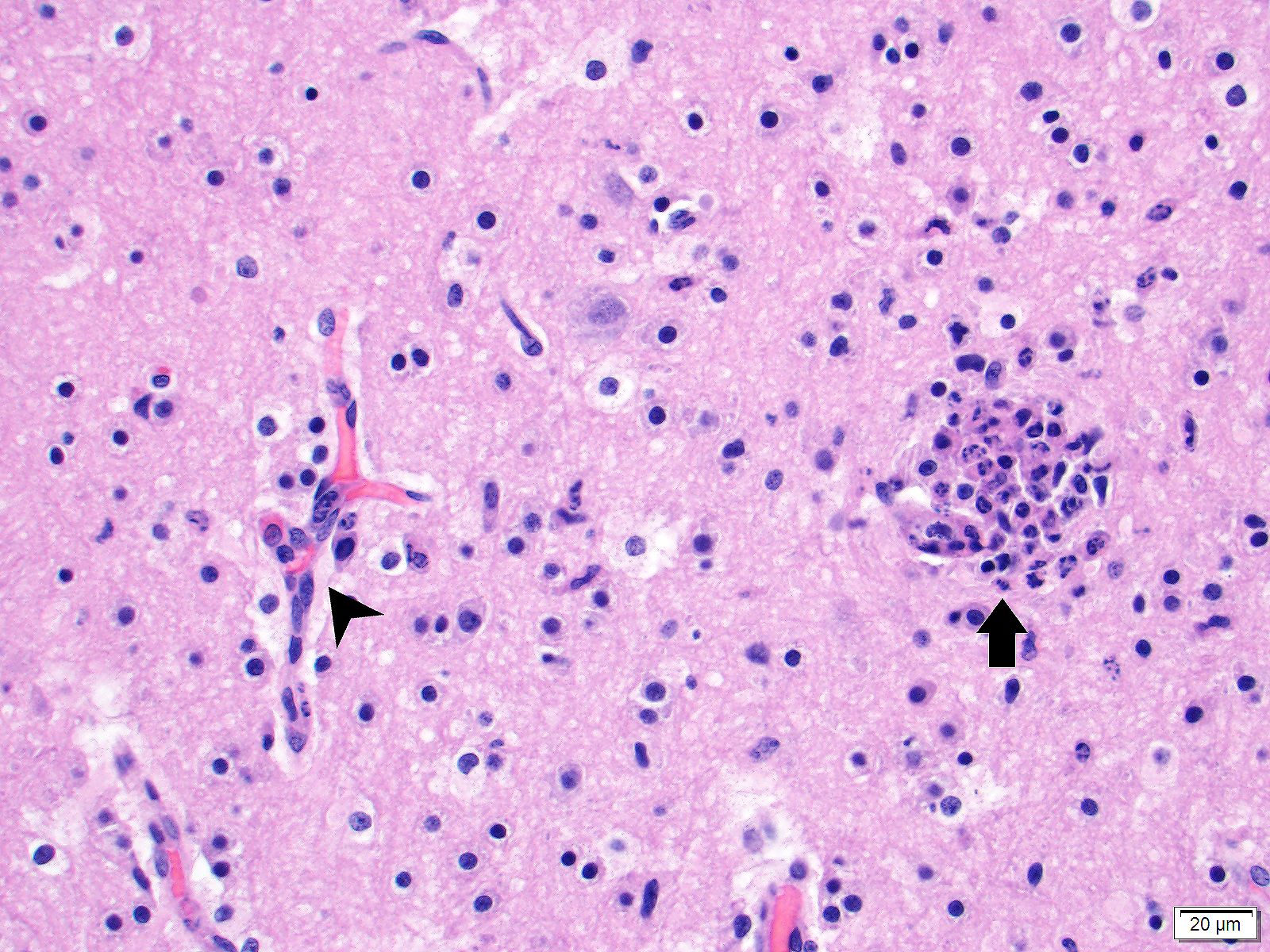

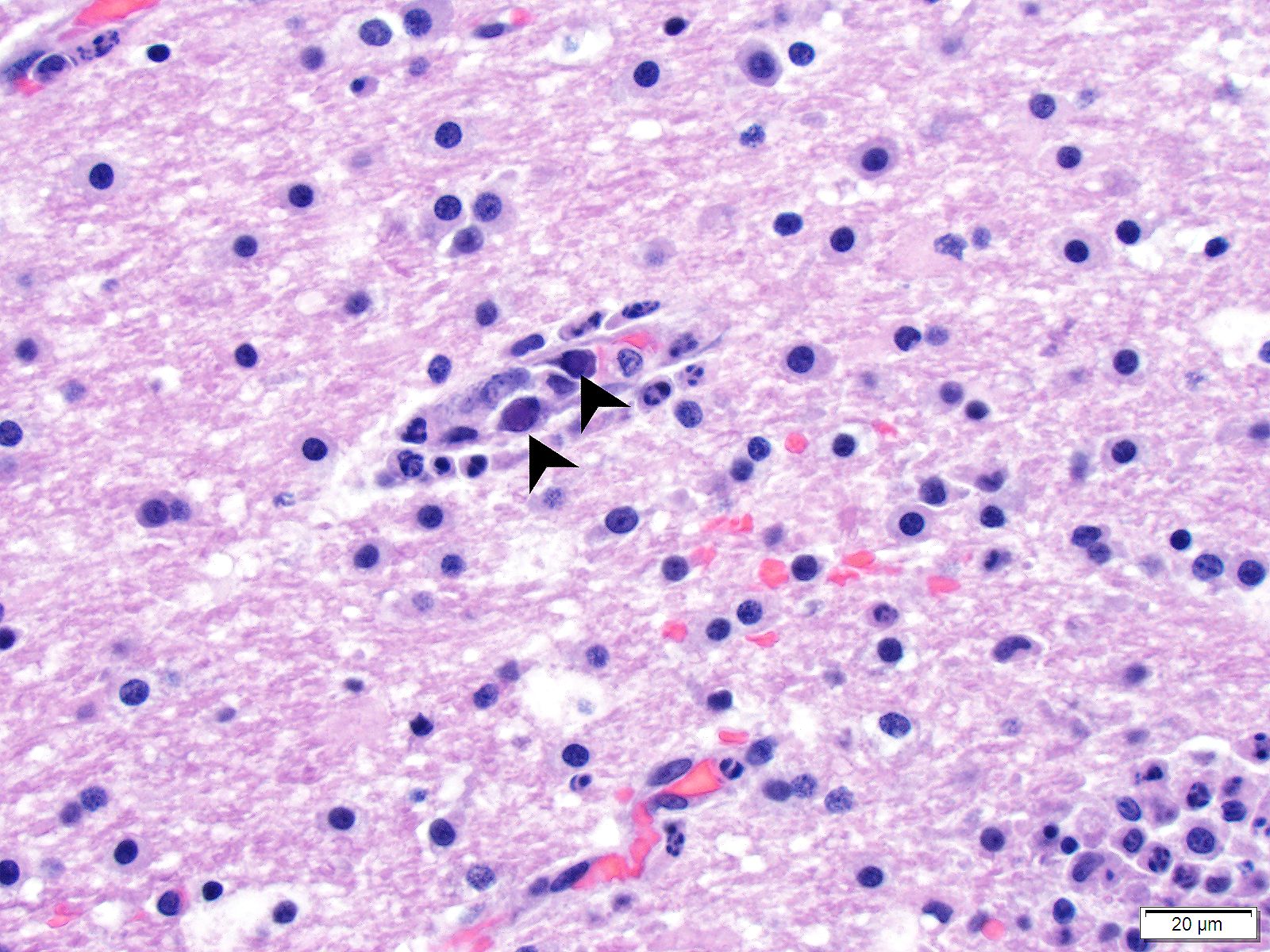

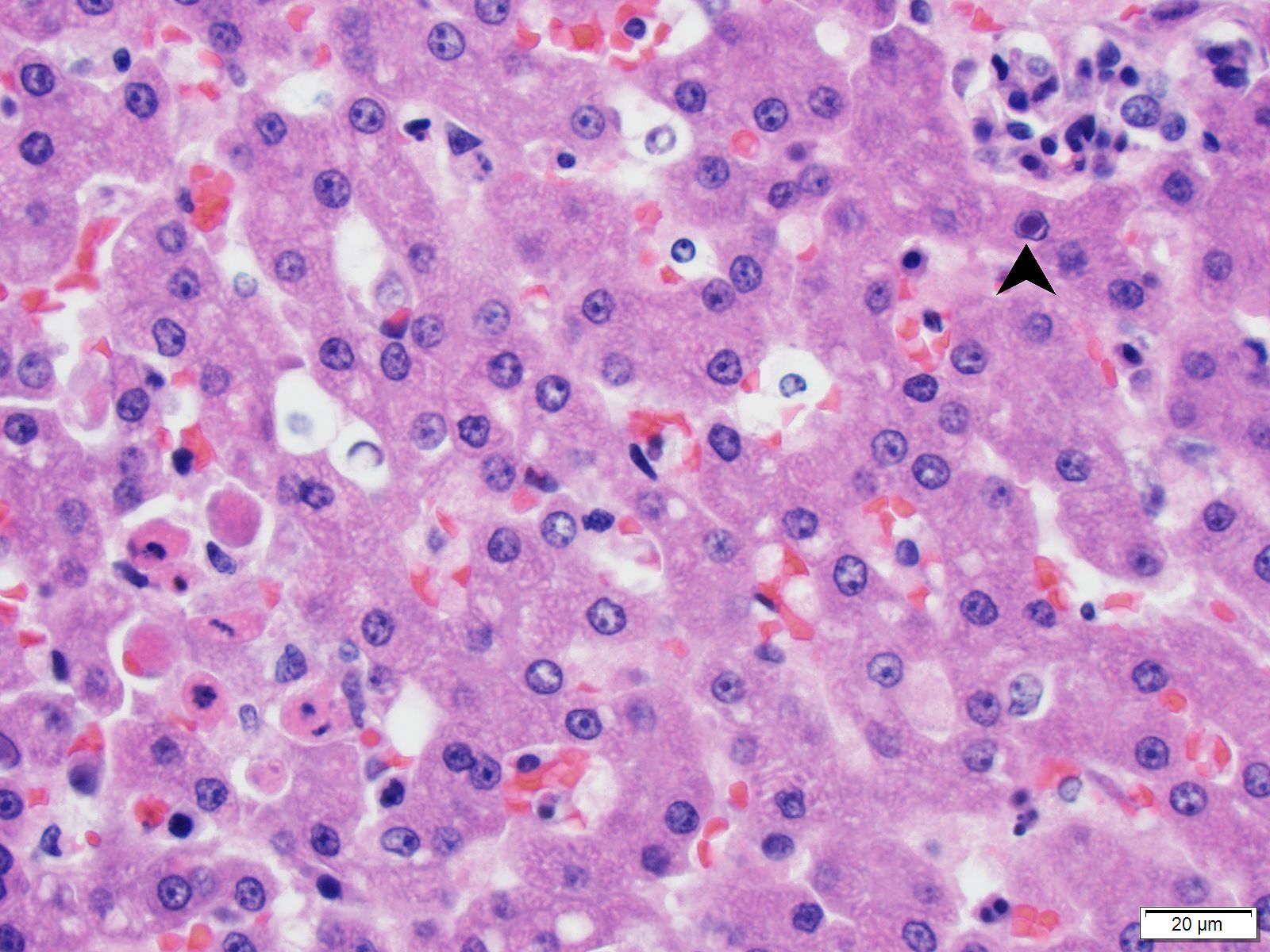

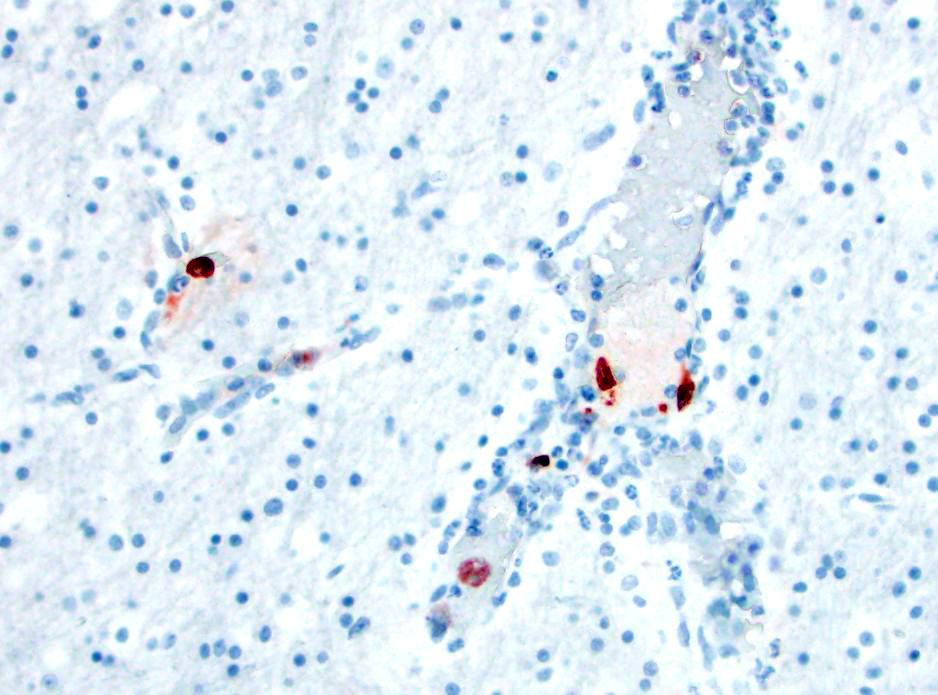

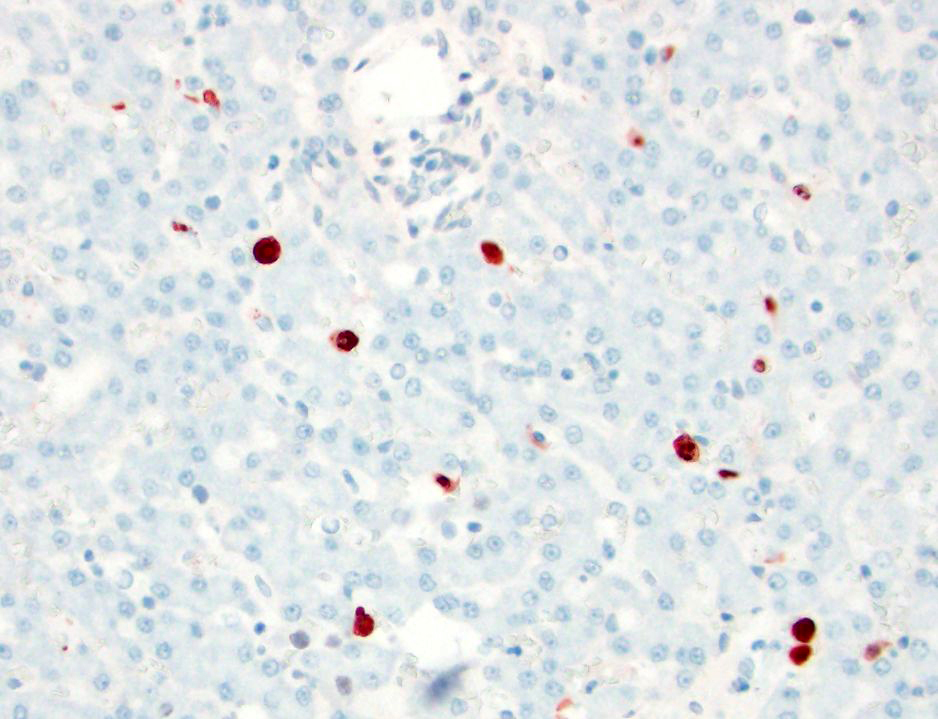

Brain (cerebrum, hippocampus, and thalamus): Widespread throughout the white and gray matter of the cerebrum, hippocampus, and thalamus, there is mild gliosis. Many distinct glial nodules composed of aggregates of mononuclear cells including oligodendroglial cells and astrocytes are present. Many glial cells within these nodules have karyorrhectic or pyknotic nuclei. Multifocally, there are occasional neurons that are surrounded by small numbers of glial cells (satellitosis). Rare neurons are hypereosinophilic and shrunken with pyknotic nuclei (neuronal necrosis) and surrounded by small numbers of glial cells (neuronophagia). Occasional neuroparenchymal and meningeal blood vessels are surrounded and partially obscured by a variably thick layer of lymphocytes, plasma cells, fewer macrophages, and rare neutrophils (perivascular cuffing). Affected blood vessels are lined by hypertrophied endothelial cells. Throughout the section, there are rare, small, randomly distributed foci of hemorrhage. Occasional endothelial cells, rare glial cells, and rare intravascular mononuclear cells have chromatin margination and a solitary, large, approximately 4-6µm in diameter, intranuclear, basophilic inclusion body that often fills the entire nucleus. The leptomeninges, typically adjacent to blood vessels, are multifocally infiltrated by small to moderate numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes.

Brain (cerebellum and brainstem) [not provided]: The histological changes are similar to those described in the cerebrum, hippocampus, and thalamus.

Liver [not provided]: There are many widely disseminated hepatocytes and rare, scattered Kupffer cells with chromatin margination and intranuclear inclusion bodies similar to those described in the brain. There are scattered small aggregates of lymphocytes with rare plasma cells and neutrophils, some of which are concentrated around blood vessels. There are rare hepatocytes with individual cell necrosis and/or apoptosis characterized by hypereosinophilia and karyorrhectic nuclei.

Immunohistochemistry:

- Brain:

- Canine adenovirus-type 1 (CAV-1): There are scattered rare endothelial cells that have strong intracytoplasmic and occasional intranuclear immunoreactivity.

- Adenovirus: There are scattered rare endothelial cells that have strong intracytoplasmic and occasional intranuclear immunoreactivity.

- Canine distemper virus: There is no immunoreactivity.

- Liver:

- CAV-1: There are occasional Kupffer cells, hepatocytes, and rare endothelial cells, with strong intracytoplasmic and occasional intranuclear immunoreactivity.

- Canine herpesvirus: There is no immunoreactivity.

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Brain (cerebrum, thalamus, hippocampus, brainstem, and cerebellum) - encephalitis, lymphohistiocytic, multifocal, moderate to marked, subacute, with gliosis, glial nodules, perivascular cuffing, lymphoplasmacytic vasculitis, endothelial and glial cell intranuclear basophilic inclusion bodies, and mild lymphoplasmacytic leptomeningitis

- Liver [not provided] - hepatitis, lymphocytic, multifocal and random, mild, subacute, with individual cell necrosis/apoptosis and intranuclear basophilic inclusion bodies

Contributor?s Comment:

Canine adenovirus type-1 (CAV-1) is a non-enveloped DNA virus, and is the causative agent of infectious canine hepatitis. The virus affects various canids, including domestic dogs, foxes, coyotes, and wolves, as well as skunks and bears.1,3,4,9 Clinical signs are typically more severe in younger animals (<1-2 years of age), ranging from asymptomatic to severe, and may include pyrexia, inappetence, lethargy, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, corneal edema, or death often without premonitory clinical signs.1,3,4 The virus has affinity for endothelial cells, hepatocytes, and mesothelium, resulting in edema, serosal hemorrhage, and hepatic necrosis.1-3 The neurological manifestation of CAV-1 infection in domestic dogs has rarely been reported, and is most commonly seen in non-domestic animal species.6,10

In this case, a diagnosis of CAV-1 infection was made based on the characteristic histologic changes and immunohistochemical results involving the liver and brain. In previously reported CAV-1 cases in domestic dogs involving the brain, characteristic lesions included hemorrhage, vasculitis, and perivascular accumulation of mononuclear cells.2,6,10 The lesions are typically seen in the brainstem, thalamus, and caudate nuclei, often sparing the cerebral and cerebellar cortices,8 although in one report, the changes were most commonly observed in the corona radiata, caudate nucleus, thalamus, pons, and leptomeninges.6

CAV-1-associated encephalitis has been more commonly associated with foxes.5,10 Under experimental conditions, the foxes developed hemorrhage predominantly affecting the brainstem and spinal cord, and variable mononuclear meningoencephalitis with perivascular cuffing.5 In the present case, the lesions differed slightly from those previously reported in dogs and foxes, with evidence of encephalitis with gliosis and glial nodules, in addition to the previously reported vascular changes. In addition, the lesions were more widespread, involving the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, brainstem, and cerebellum.

Neurological signs associated with CAV-1 have been attributed to vascular damage within the central nervous system,3,4,10,11 although other possibilities include hepatic encephalopathy and/or concurrent infection with canine distemper virus (CDV).11 It has been suggested that different CAV-1 strains may have tropism for the endothelium of the central nervous system.2,10 However, to our knowledge, sequence analysis has not been performed to confirm this hypothesis. In this case, the cause of the reported seizures likely involved a combination of encephalitis and central nervous system vascular involvement. Although speculative, it is possible that the differences in the lesions and distribution of the lesions from the previously reported cases may have been due to the characteristics of the CAV-1 strain and/or the host immune response.

Susceptible dogs are exposed to CAV-1 via oronasal route through contact with infectious saliva, feces, urine, or respiratory secretions, or through direct animal-to-animal contact.1,4,10,11 The virus initially replicates in the tonsillar crypts resulting in tonsillitis, followed by spread to the local lymph nodes and systemic circulation.1,3,8 Viremia typically lasts 4-8 days and the virus spreads to the liver, endothelial cells, and mesothelial cells.1,3,10 The virions exit the cells by cell lysis, resulting in cell death and tissue injury.1,9 Characteristic histological lesions typically involve the liver, and range from randomly scattered foci of hepatocellular necrosis to widespread centrilobular necrosis.1,3 Intranuclear inclusion bodies are often found in hepatocytes, vascular endothelium, and Kupffer cells.1,3 Other lesions that may be seen include corneal edema/iridocyclitis (typically between 14 to 21 days post infection), gallbladder wall edema, interstitial nephritis, hemorrhagic enteritis, laryngitis, tracheitis, pneumonia, and ecchymotic and petechial hemorrhages.1-4,6,11

Differential diagnoses for viral encephalitis in dogs include CDV, rabies virus, and canine herpesvirus. Coinfection is possible, with reports of CDV and CAV-1 resulting in an increased mortality rate.6 CDV infection may be characterized by both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies. CDV infection was excluded in this case based on the negative immunohistochemistry results. Rabies was considered unlikely based on negative direct fluorescent antibody testing result for rabies antigen. Canine herpesvirus (CHV)-associated meningoencephalitis has been reported in natural and experimental conditions.7 In one case series involving natural canine herpesvirus encephalitis, lesions were characterized by randomly distributed glial nodules throughout the white and gray matter of the cerebrum, brainstem, and cerebellum, as well as lymphocytic meningitis and cerebellar cortical necrosis.7 Although CHV immunohistochemistry was not performed on the brain in this case, the liver was immune-negative, and CHV infection was considered unlikely.

Contributing Institution:

The University of Minnesota, College of Veterinary Medicine, Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. https://www.vdl.umn.edu

JPC Diagnosis:

Thalamus and cerebrum: Vasculitis, lymphocytic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with glial nodules and intraendothelial intranuclear viral inclusions.

JPC Comment:

The moderator and conference participants discussed the presence of glial nodules, which are multifocal proliferation of microglial cells in reaction to injury in the CNS and neuronal necrosis. Canine adenovirus 1 is not apparently associated with the glial nodule formation, and glial nodule formation is not an expected finding in canine adenovirus-1 infection. All agreed that the contributor did an excellent workup to rule out canine distempervirus and canine herpesvirus-1. Both viruses can cause neuronal necrosis with glial nodule formation and would be top differentials based on this H&E section.

Two helpful histologic features which indicate that this animal is juvenile are the diffuse high concentration of glial cells and the prominence of the undifferentiated glial and neuronal precursors (?rests?) in the periventrular tissue. Both of these findings are normal in puppies.

Most vertebrate species can be infected by viruses of the Adenovirus family, but individual viruses have narrow host ranges, are persistent, and generally are subclinical or associated with mild respiratory infections.8 There are notable exceptions such as CAV-1, deer adenovirus, and several avian adenoviruses, which cause important diseases in their host species.8 There are five genera in the Adenoviridae family: Mastadenovirus, Aviadenovirus, Atadenovirus, Siadenovirus, and Ichtadenovirus. The name adenovirus is derived from how the virus was initially identified: as a cause of cellular degeneration in human adenoid cultures.8

Canine adenovirus 1, which affects domestic and wild canids, skunks, coatis, and bears, was discovered in 1954 as the causative agent of fox encephalitis.8,9 The contributor provides an excellent overview of CAV-1 infection in dogs and non-domestic animals. A recent report by Pereira et al described natural CAV-1 infection and death in captive maned wolf puppies.9 On necropsy, findings mirrored those seen in dogs, with nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis, necrotizing hepatitis and splenitis, and intranuclear inclusion bodies in hepatocytes (1 of 2 pups) and kidneys (2 of 2 pups).9

Canine adenovirus 2, another virus in the Mastadenovirus family, is a member of the canine respiratory disease complex and infection is limited to the respiratory system.9

Significant adenoviruses in avian species fall within the Aviadenovirus, Atadenovirus, and Siadenovirus genera.9 Fowl adenovirus 1, a member of Aviadenovirus genus, causes quail bronchitis and is characterized by necrotizing tracheitis, air sacculitis, conjunctivitis, and gastrointestinal disease, with a high mortality in young quail.9 Another member of the Aviadenovirus genus is fowl adenovirus 4, which causes hydropericardium syndrome in chickens, with the most severe disease occurring around one month of age.9 In addition to the pericardial effusion, pulmonary edema and enlargement of the kidneys and liver may be seen.9 Within the Siadenovirus genus, turkey adenovirus 3 causes hemorrhagic enteritis in turkeys over a month of age, and two closely related (serologically indistinguishable) viruses cause marble spleen disease in pheasants and avian adenovirus splenomegaly in chickens.9

References:

- Brown DL, Van Wettere AJ, Cullen JM. Hepatobiliary system and exocrine pancreas. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th Elsevier Mosby; 2017.

- Caudell D, Confer AW, Fulton RW, et al. Diagnosis of infectious canine hepatitis virus (CAV-1) infection in puppies with encephalopathy. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005; 17: 58-61.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th, vol. 2. Saunders Elsevier; 2016.

- Decaro N, Martella V, Buonavoglia C. Canine adenoviruses and herpesvirus. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2008; 38: 799-814.

- Green RG, Ziegler NR, Green BB, Dewey ET. Epizootic fox encephalitis. I. General description. Am J Epidemiol. 1930; 12: 109-129.

- Hornsey SJ, Philibert H, Godson DL, Snead ECR. Canine adenovirus type 1 causing neurological signs in a 5-week-old puppy. BMC Vet Res. 2019; 15: 418.

- Jager MC, Sloma EA, Shelton M, Miller AD. Naturally acquired canine herpesvirus-associated meningoencephalitis. Vet Path. 2017; 54: 820-827.

- MachLachlan NG, Dubovi EJ. In: MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ, eds. Fenner?s Veterinary Virology. 5th ed. San Diego, CA: Elsevier. 2017; 217-227.

- Pereira FMAM, de Oliveira AR, Melo ES, et al. Naturally Acquired Infectious Canine Hepatitis in Two Captive Maned Wolf (Chrysocyon bracyurus) puppies. J Comp Path. 2021; 182: 62-68.

- Pintore MD, Corbellini D, Chieppa MN, et al. Canine adenovirus type 1 and Pasteurella pneumotropica co-infection in a puppy. Vet Ital. 2016; 52: 57-62.

- Sykes JE. Infectious canine hepatitis. In Sykes JE, ed. Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. Saunders; 2014.