Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 3, Case 1

Signalment:

2-3 month old, intact male guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus)

History:

These guinea pigs were from a control group on study at a contract research organization. A nodule was found in the heart during post-life processing. No clinical signs were noted prior to euthanasia.

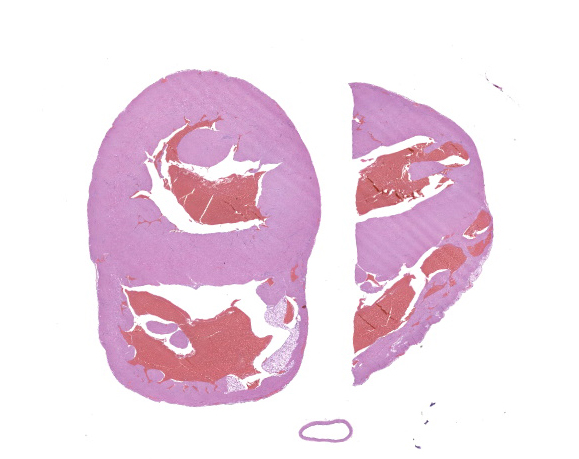

Gross Pathology:

A poorly-demarcated, tan nodule expands the right or left ventricular free wall or the interventricular septum of the heart.

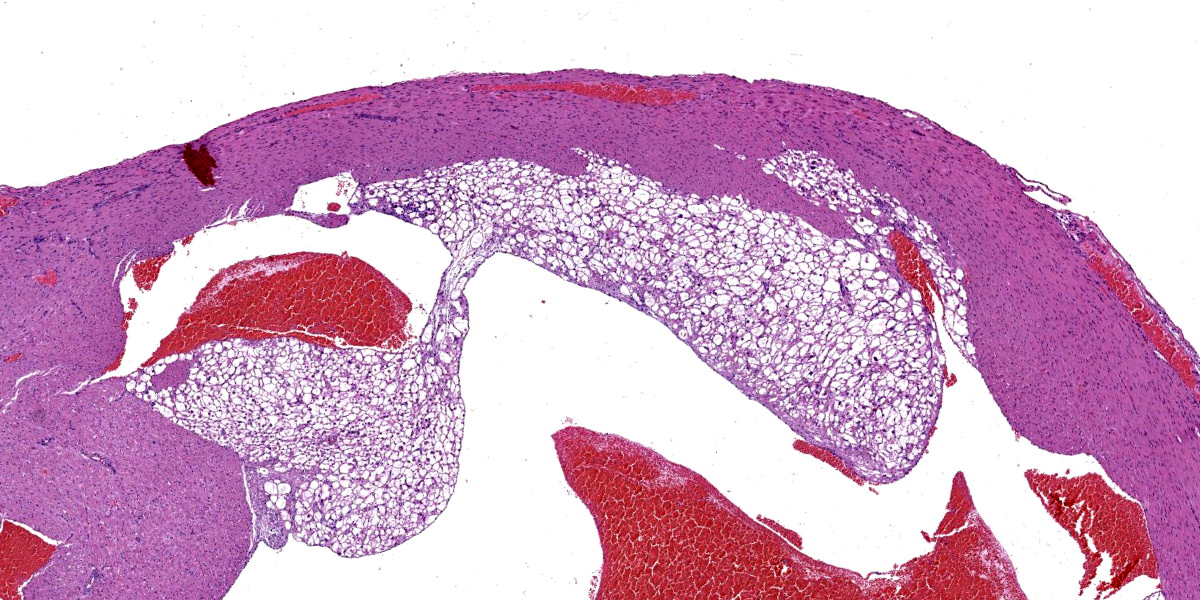

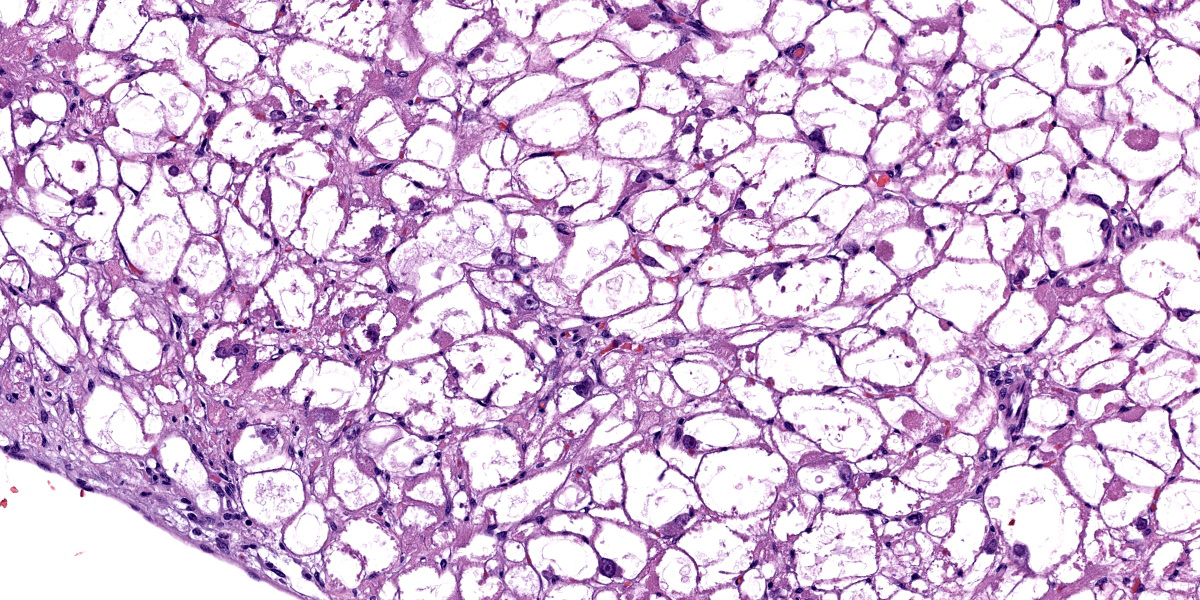

Microscopic Description:

The subendocardial muscle is regionally effaced by expansile, well-circumscribed foci of atypical cardiac myocytes that are arranged in bundles and streams. Atypical cardiac myocytes are plump polygonal and have distinct cell borders. These cells are markedly distended by clear vacuoles, pale eosinophilic granular material, and acidophilic bodies. Nuclei are round; have finely to coarsely stippled chromatin; frequently contain a single prominent nucleolus; and are occasionally surrounded by radiating, linear sarcoplasmic processes (spider cells). The surrounding cardiac myofibers are minimally compressed. Small numbers of mixed mononuclear cells multifocally infiltrate the normal cardiac muscle.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Heart: Severe regional cardiac myofiber vacuolar degeneration and glycogen accumulation.

Condition: Cardiac rhabdomyomatosis

Contributor’s Comment:

The pathogenesis of this condition is still debated, though it is considered an incidental finding. Common features across veterinary species include the presence of PAS-positive material (interpreted as glycogen) within sarcoplasmic vacuoles and the formation of spider cells, which represent an artifact of glycogen loss during histologic processing.4-10 Some sources attribute this condition to a defect in glycogen storage or metabolism.3,9 An association with hypovitaminosis C (scurvy) has been suggested in guinea pigs, but is not well-established.9

Recent veterinary literature indicates that in swine, the abnormal myocytes contain ultrastructural and immunohistochemical features of both postnatal cardiac myocytes and Purkinje cells. These characteristics, in conjunction with the age predilection for juvenile animals, support the contention that this may represent a congenital dysplasia or a tumor arising from a pluripotent embryonic cell.3,12 In humans, cardiac rhabdomyomas represent the most common primary pediatric cardiac neoplasm and, interestingly, are often associated with tuberous sclerosis complex.5

Contributing Institution:

Pathology Department

Charles River Laboratories – Mattawan

www.crl.com

JPC Diagnosis:

Heart, myocardium: Glycogenosis, multifocal, moderate.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Major Daniel Bland, Chief of Histology (Veterinary Pathology) at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) and his cases were anything but mundane. This first entity is a classic in the guinea pig, though as the contributor also notes there are occasional case reports in other species as well. Recently, there was a short report of this condition in Göttingen Minipigs as well.1 Tissue identification and lesion recognition was relatively simple for this case, so we focused on better characterizing the plump, atypical cardiac myocytes that the contributor so nicely describes/ Similar to the table provided, we ran IHCs and special stains for Periodic-Acid Schiff (with and without diastase), muscle specific actin, desmin, GFAP, IBA1, NSE, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. These atypical myocytes were strongly PAS-positive within the cytoplasm, though this staining intensity was greatly diminished by treatment with diastase, consistent with interpretation of these vacuoles as containing glycogen. Compared with normal cardiac myocytes, these atypical myocytes also had minimal cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for desmin and muscle specific actin. Chromogranin and synaptophysin were immunonegative.

Conference participants had a few interesting takeaways from this case. Foremost, there was the observation that the PAS section following diastase treatment was quite washed out. As Dr. Bruce Williams reminded participants, cells with increased glycogen content include hepatocytes, neurons, and cardiac/skeletal myocytes – it is hardly a surprise then that the staining profile of these cells should change with this glycogen content also being digested. Participants also debated how to best describe this condition, with the consensus falling on a moderate severity given the limited ancillary changes within the heart (i.e. degeneration and necrosis of adjacent myocytes).

There are several other lesions to be aware of in the heart of guinea pigs which were not present in this case. These include rare mineralization of cardiac myocytes which may be accompanied by fibrosis and minimal mononuclear cell infiltration; alone this is typically subclinical.9 Additionally, the underlying cause for myocardial protein aggregates in pet guinea pigs has been described,11 with accumulation of these alpha B crystallin (a small heat shock chaperone protein) being most common in the right ventricular free wall, though they may also be found within papillary muscles within the left and right ventricles of the heart as well.

References:

- Feller LE, Sargeant A, Ehrhart EJ, Balmer B, Nelson K, Lamoureux J. Cardiac Rhabdomyoma in Four Göttingen Minipigs. Toxicol Pathol. 2023 Jan;51(1-2):61-66.

- Holley D, et al. Diagnosis and management of fetal cardiac tumors; a multicenter experience and review of published re ports. J Am Coll Cardiol, p. 516-520, 1995.

- Jacobsen B, et al. Proposing the term purkinjeoma: Protein Gene Product 9.5 Expression in 2 Porcine Cardiac Rhabdomyoma Indicates Possible Purkinje Fiber Cell Origin. Vet Pathol. 2010;47(4):738-740.

- Kizawa KK, et al. Cardiac rhabdomyoma in a Beagle dog. Journal of Toxicologic Pathology. 2002; 15(1):69-72.

- Kobayashi TT, et al. A Cardiac rhabdomyoma in a guinea pig. Journal of Toxicologic Pathology. 2010;23(2):107-110.

- Kolly C, et al. Cardiac rhabdomyoma in a juvenile fallow deer (Dama dama). Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2004;40(3):603- 606.

- Krafsur G, et al. Histomorphologic and immunohistochemical characterization of a Cardiac Purkinjeoma in a Bearded Seal (Erignathus barbatus). Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine. 2014.

- Pereira PA, et al. Cardiac rhabdomyoma in a slaughtered pig. Cienc. Rural, Santa Maria. 2018; 48(10):e20180460.

- Percy DH, Griffey SM, and Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Pub, 2016, 241-242.

- Radi ZA, Metz Z. Canine cardiac rhabdomyoma. Toxicologic Pathology. 2009;37(3):348-350.

- Southard T, Kelly K, Armien AG. Myocardial protein aggregates in pet guinea pigs. Vet Pathol. 2022 Jan;59(1):157-163.

- Tanimoto T, Ohtsuki Y. The pathogenesis of so-called cardiac rhabdomyoma in swine: a histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Virchows Archiv. 1995;47(2):213-221.