CASE 1: MK1905835 (4151722-00)

Signalment:

18-year-old female squirrel monkey, Saimiri sciureus

History:

Euthanized for because of cardiac enlargement and symptoms of heart failure.

Gross Pathology:

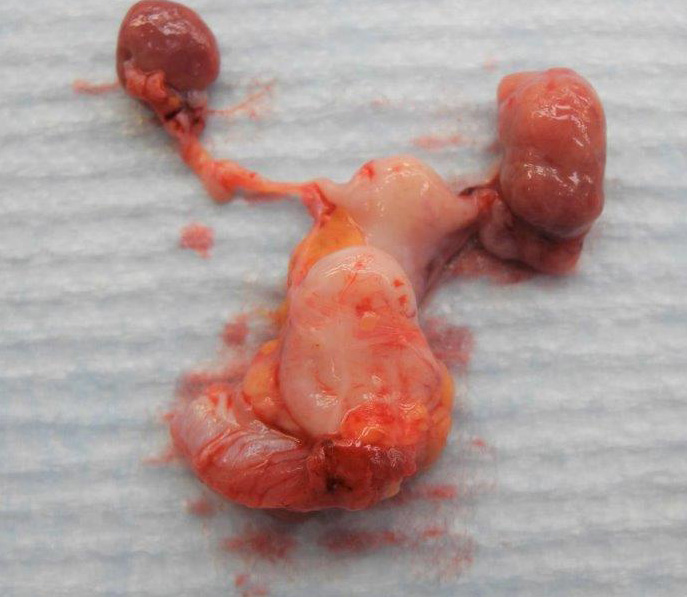

The heart was severely enlarged at 1.25% of body weight and thoracic and peritoneal effusion was present. The left ovary was found to be enlarged due to 7 mm diameter, firm, tan nodule with an irregular surface. The cut surface was solid.

Laboratory results:

N/A

Microscopic description:

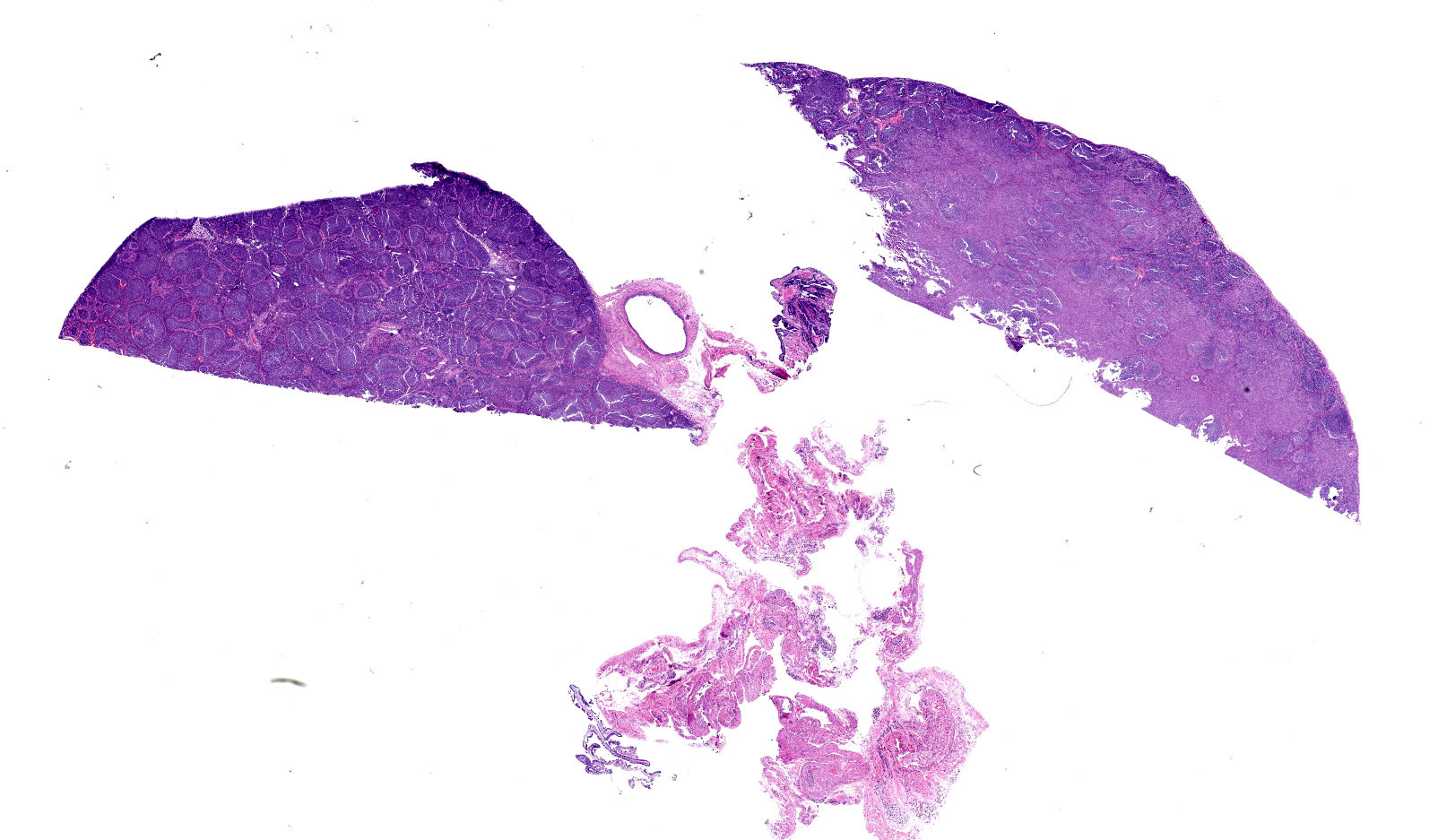

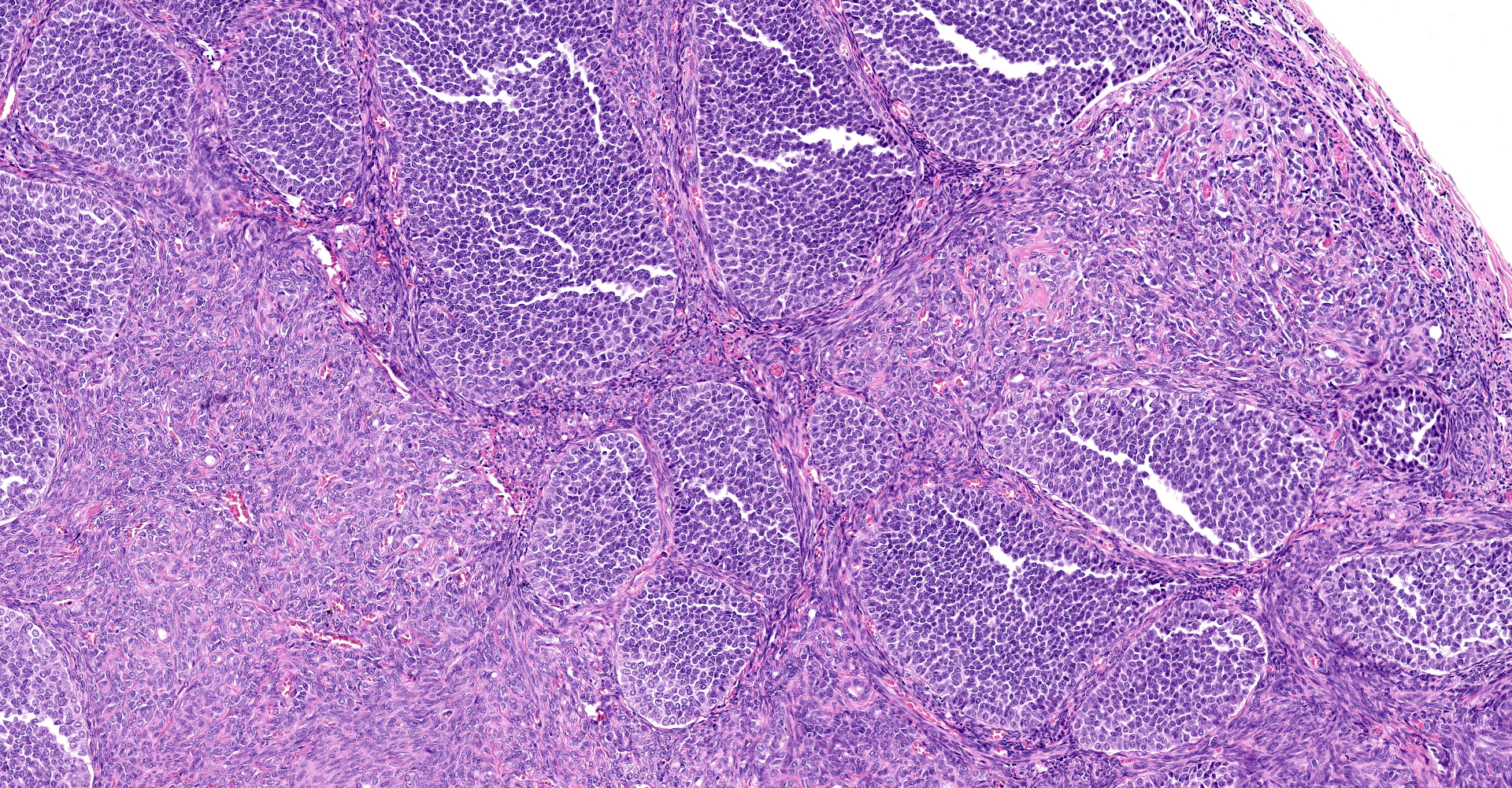

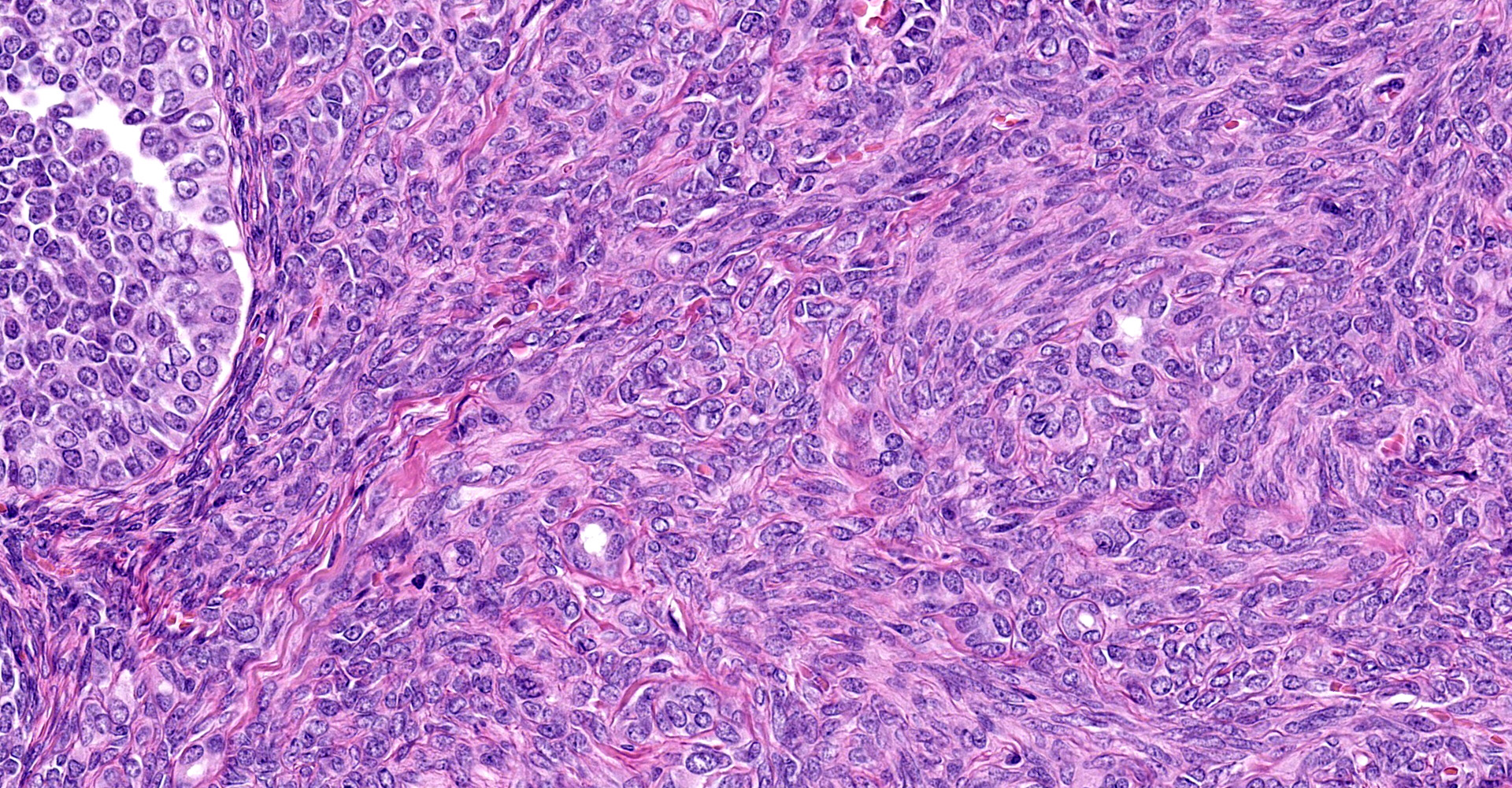

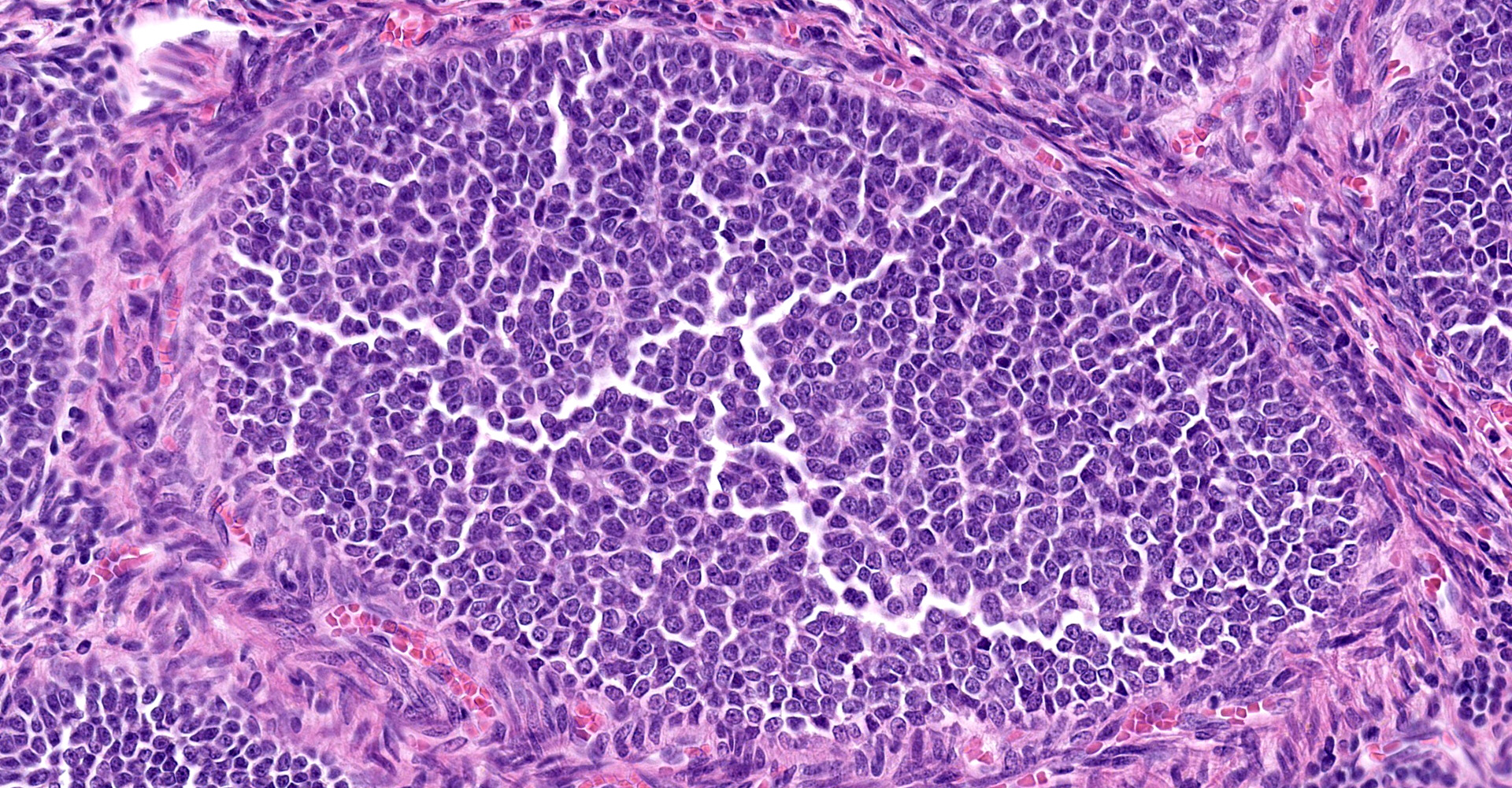

(Slides may have one or two sections of ovary) The tumor is well-demarcated and compresses adjacent ovary. It consists of widely separated follicle-like structures separated by bands of stroma. Most of the follicles are oval but some are irregular in shape. Some are cystic. Neoplastic cells line up perpendicular to the stroma; occasional rosettes are present. They are composed of cuboidal cells with scant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are round to oval with inconspicuous nucleoli. PAS stain reveals some of the rosettes contain PAS positive material. The stromal cells are elongated. Stroma is composed of elongated spindle cells and numerous tubules. Mitotic figures are not observed.

Remaining ovary has hyperplasia of follicles the predominance of which lack ova and/or progression to antral follicles. The periphery of the ovary has small numbers of primary follicles. The uterus has normal endometrium myometrium.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Ovary: Granulosa cell tumor.

Ovary: Granulosa cell hyperplasia, senescent change.

Contributor's comment:

Ovarian tumors can arise from the outer epithelium (papillary cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma), the interior sex cords and stroma, and germ cells (dysgerminoma and teratoma). "Sex cord" is a term that denotes the possible embryologic origin of cells in the mesonephros.14 SCSTs are the most commonly reported ovarian tumor in macaques.4 They have been reported in rhesus, stump-tailed and bonnet macaques, baboons, gibbons and chimpanzees.3,12

Sex cord stromal tumors (SCST) are classified as either granulosa tumor (GCT), thecoma, or luteoma. GCT are often cystic and exude bloody fluid on cut section. They can be hormonally active and cause either hyperestrogenism or masculine behavior. They can develop from ovarian remnants. The follicular structures that they form often have rosettes with eosinophilic material in the center, (Call-Exner bodies). They can be either benign or malignant. GCT are commonly reported in cows, mares and dogs.7,14 Inhibin produced by GCT which can cause atrophy of the opposite ovary.16

Other subtypes of SCST's include thecomas, luteoma, and Brenner's tumor (a type of epithelial stromal tumor). Thecomas have spindle shaped cells that are often vacuolated due to lipid. They tend to be solid. Luteomas have luteinized cells with abundant cytoplasm.3,4,7,12 The latter two tumors are benign.

Also described in older squirrel monkeys is the proliferation of anovulatory follicle-like clusters of granulosa cells in the opposite ovary.3 An early paper describes granulosa cell aggregates in both ovaries; this may have been the hyperplastic lesions that we see in this case.14 A retrospective study of archived squirrel monkey ovaries found the granulosa cell proliferation was consistent feature starting at 8 years old. These occur prior to loss of reproductive ability and may be a feature of aging ovaries in this species. They are positive for anti-Müllerian hormone.16

In this case, the tumor is primarily solid with abundance of very cellular stroma suggests a granulosa-theca tumor. The ovary of a different, 17-year-old squirrel monkey has similar proliferation of anovulatory follicles.

Contributing Institution:

NIH, Division of Veterinary Medicine

Diagnostic and Research Services Branch

28 Library Drive

Bethesda, Maryland 20892

JPC diagnosis:

Ovary: Sex cord stromal tumor (granulosa-theca cell tumor).

JPC comment:

Granulosa cell tumor (GCT) is most common in the mare,7,15 but also occurs with some frequency in the cow,7,15 the queen,2 the gerbil,9 and nonhuman primates.5 Less frequently, GCT has been reported in the rock hyrax,1 the Longjaw mudsucker fish (Gillichthys mirabilis),8 and some prosimians (Lesser bushbaby, Pygmy slow loris, Slender loris).11

In humans, GCT are classified into two groups. The first primarily affects post-menopausal women and has an association with a mutation in FOXL2, and the second is a juvenile type that primarily occurs in children and young adults and is not associated with FOXL2 mutation. Immunohistochemical stains such as inhibin, calretinin, steroid-factor-1 (SF-1), and FOXL2 are usually positive in sex cord-stromal tumors, while epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) is usually negative. However, the availability of validated products may limit their use in veterinary cases.6

With a variety of hormone receptors on granulosa cells, and the hormones produced by these cells, hormone therapy has been explored as a treatment modality. Previous methods have focused primarily on gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists/antagonists, estrogen antagonists, and synthetic progestins, but have met with limited success. Androgen antagonism has seen success in prostate, breast, and endometrial carcinoma, but has efficacy in the treatment of GCT has not yet been explored. Also recently explored is immunotherapy targeting the programmed cell death 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 relationship, with one study (NCT02923934) currently in Phase 2 trials.12

Epidermal growth factor-like domain-containing protein 7 (EGFL7) is a critical oncogene in the development of several cancers and its expression is a predictive biomarker for cervical cancer. MicroRNA 126 (miR-126) embeds in the genomic region of EGFL7, silencing expression of this gene in pleural mesothelioma. Using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), it was discovered that expression of miR-126 was significantly lower in malignant and benign GCT tissues than non-neoplastic ovarian cyst tissue. A mouse model with overexpression of miR-126 resulted in significantly smaller tumors than in control mice, suggesting the possibility of miR-126 as a new biomarker for GCT. This also may represent a future therapeutic avenue to explore.16

Conference discussion included the paraovarian cyst in section, and its possible origins. Cysts arising from the mesonephric tubules include cystic epoophoron, cyst rete ovarii, extraovarian rete cyst, and cystic paroophoron. Mesonephric duct cysts arise from peristent mesonephric ducts, and fimbrial cysts and hydatid of Morgagni arise from paramesonephric ducts.

This case includes a prominent thecal component, which is consistent with many canine sex cord stromal tumors. While often called simple granulosa cell tumors, in order to more fully capture the thecal component we prefer the diagnosis above.

References:

1. Agnew D, Nofs S, Delaney MA, Rothenburger JL. Xenartha, Erinacoemorpha, Some Afrotheria, and Phloidota. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. San Diego, CA:Elsevier. 2018:525.

2. Agnew DW, MacLachlan NJ. In: Tumors of the genital system. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:690-698.

3. Chalifoux L. Granulosa cell tumor cell tumor, ovary, stump-tail macaque and granulosa-theca cell tumor, ovary, squirrel monkey. In Jones TC et al eds. Nonhuman Primates II, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1993; 155-160

4. Cline J, Wood C, Vidal J et. al. Selected background findings and interpretation of common lesions in the female reproductive system in macaques. Tox. Path. 2008; 36: 142S-163S

5. Durkes A, Garner M, Juan-Salles C, Ramos-Vara J. Immunohistochemical characterization of nonhuman primate ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors. Vet Pathol. 2012;49(5):834-838.

6. Folkins AK, Longacre TA. Immunohistology of the Female Genital Tract. In: Dabbs DJ ed. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry, Theranostic and Genomic Applications, 5th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. 2019;662-717.

7. Foster RA. Female Reproductive System and Mammae. In: Zachary JF ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, 6th Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2017:1161-1162.

8. Frasca S, Wolf JC, Kinsel MJ, Camus AC, Lombardini ED. Osteichthyes. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. San Diego, CA: Elsevier. 2018:965.

9. Guzman-Silva MA, Costa-Neves M. Incipient spontaneous granulosa cell tumor in the gerbil, Meriones unguiculatus. Lab Anim. 2006;40(1):96-101.

10. Kennedy P, Cullen J, Edwards J et al. WHO Histological Classification of Tumors of the Genital System of Domestic Animals Second Series volume IV, 1998; 24-25

11. McAloose D, Stalis IH. Prosimians. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. San Diego, CA:Elsevier. 2018:339.e11.

12. Mills AM, Chinn Z, Rauh LA, et al. Emerging biomarkers in ovarian granulosa cell tumors. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2019;29:560-565.

13. Nagarajan P, Venkatesan R, Mahesh Kumar M et al. Granulosa-theca cell tumor with luteoma in the ovary of a bonnet monkey (Macaca radiata). J. Medical Primatology 2005; 34: 219-223

14. Rewel R. Uterine fibromyoma and bilateral ovarian granulosa cell tumor cell tumor in a senile squirrel monkey, Saimiri sciurea. J. Path Vol LXVIII, 1954; 68: 291-293

15. Schlafer D, Foster R. Female genital system. In Maxie M G ed. Jubb and Kennedy Pathology of Domestic Animal, volume 3, Elsevier, St. Louis, Missouri, 2007; 375-377

16. Tu J, Cheung HH, Lu G, Chan CLK, Chen Z, Chan WY. microRNA-126 is a tumor suppressor of granulosa cell tumor mediated by its host gene EGFL7. Frontiers in Oncology. 2019;9:486.

17. Walker M, Anderson D, Herndon J et al. Ovarian aging in squirrel monkeys, Saimiri sciureus. Reproduction 2009; 138: 793-799