Signalment:

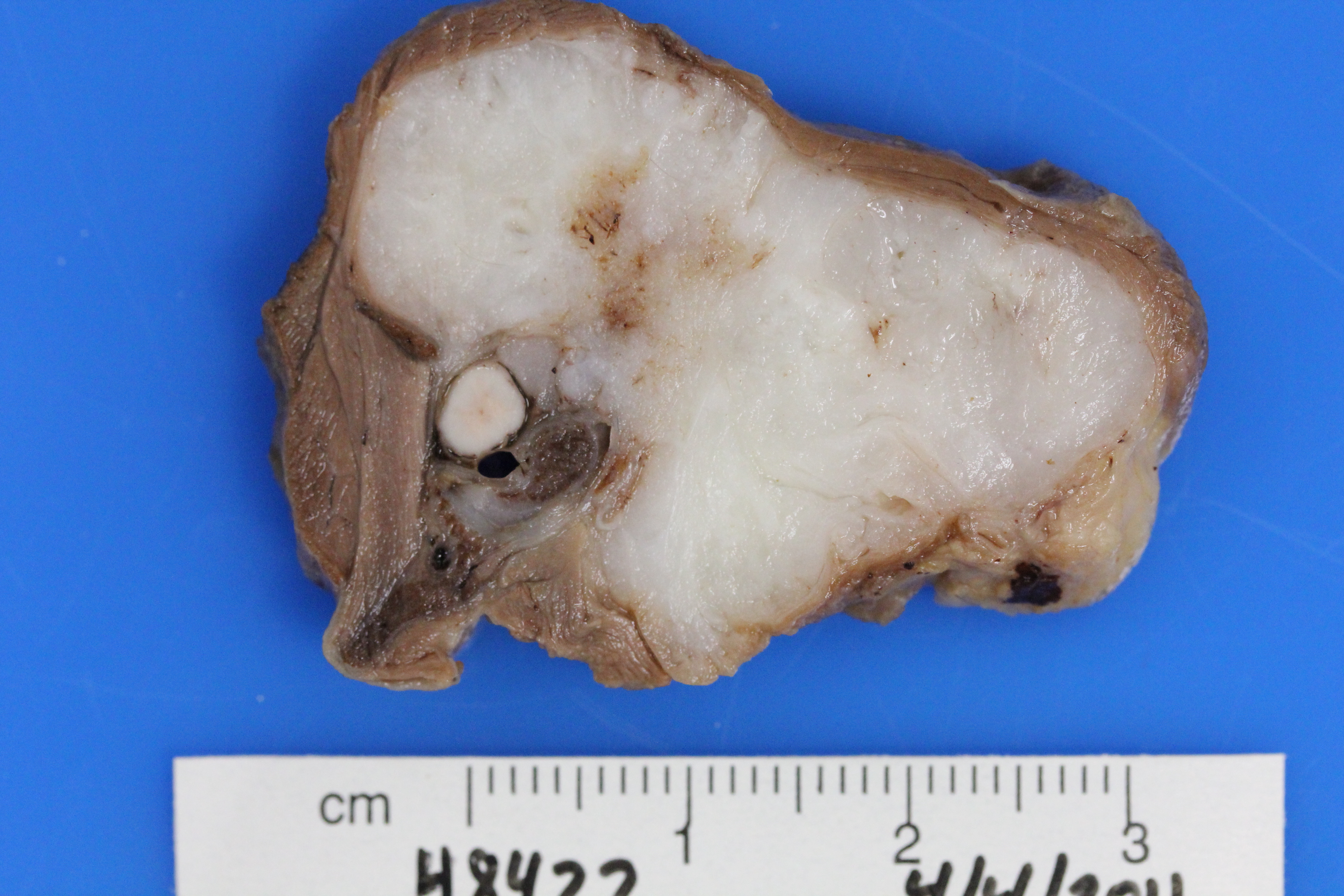

Gross Description:

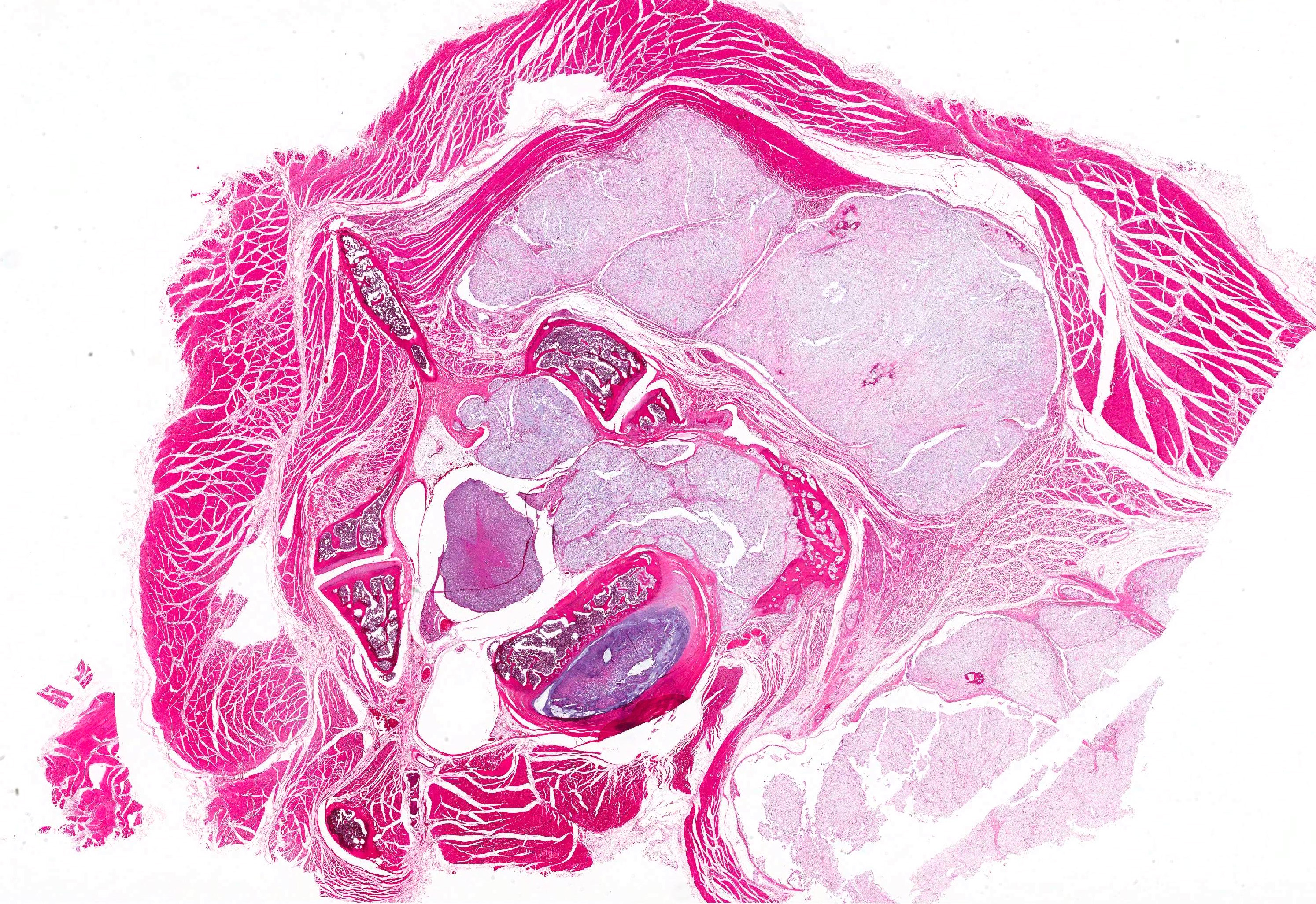

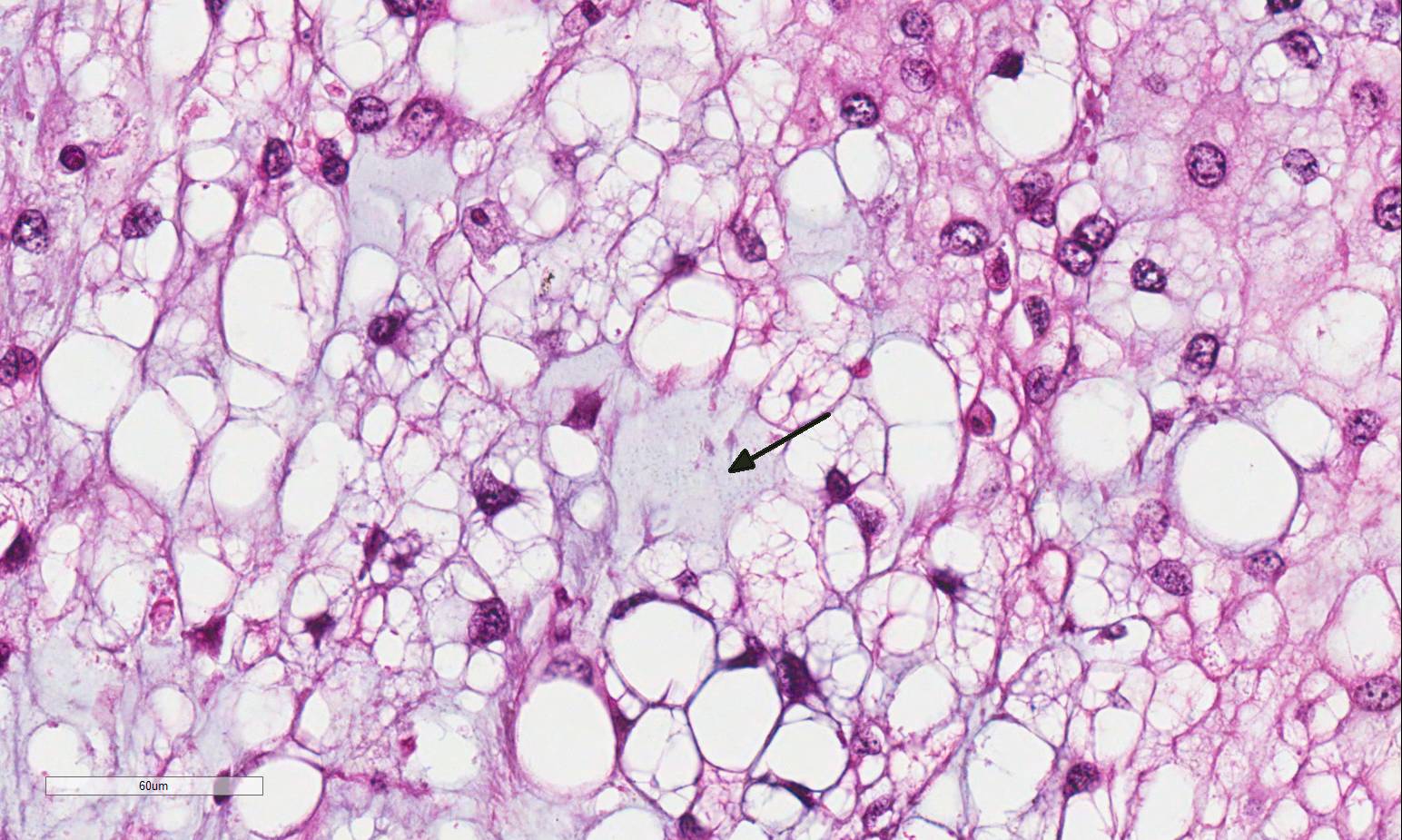

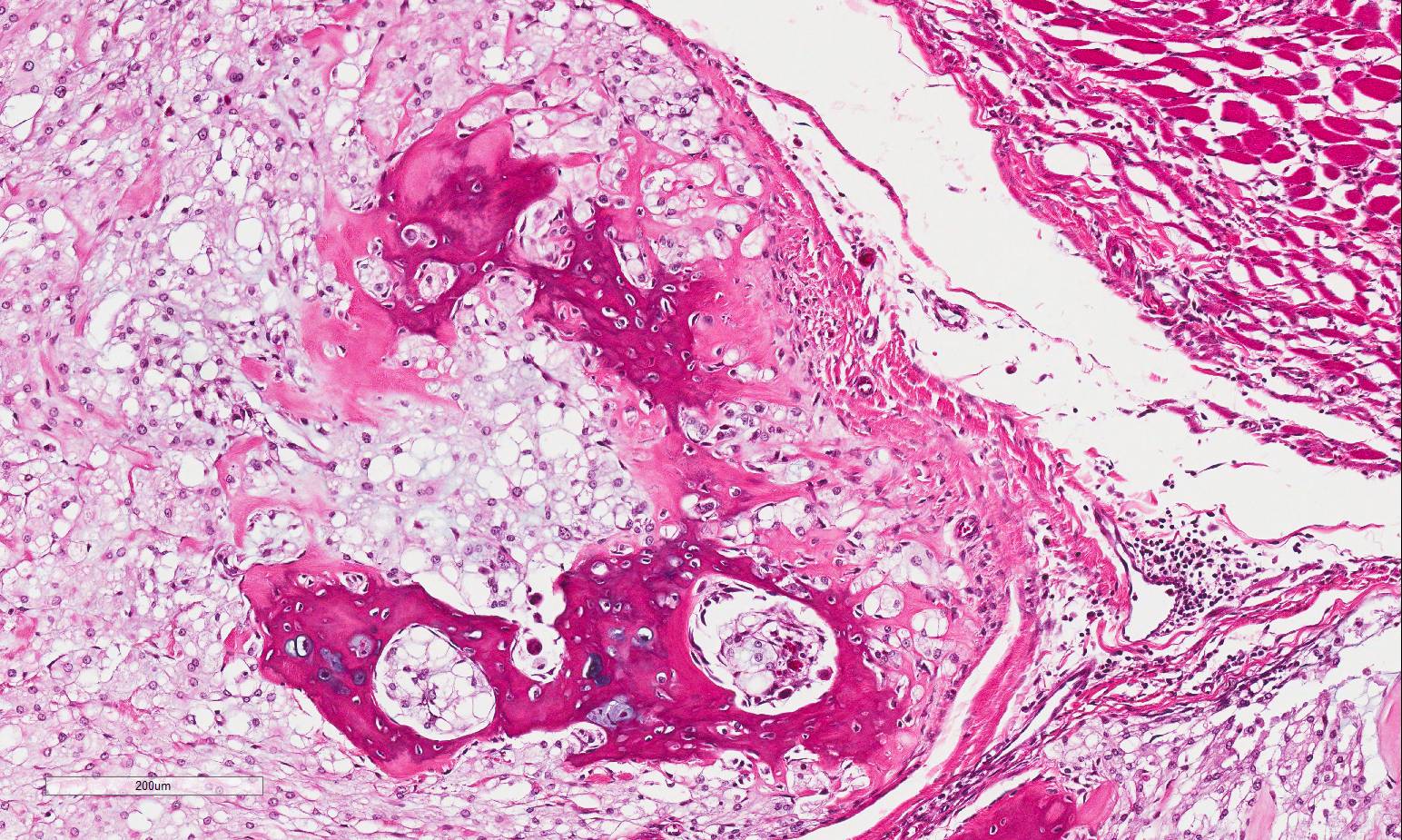

Histopathologic Description:

Vertebral bone has scalloped borders, with osteoclasts in Howships lacunae. Fragmented woven bone (reactive bone) is interspersed with numerous plump osteoblasts and fibroblasts. Neoplastic compression of the cervical spinal cord results in shifting of the ventral medial fissure away from the mass. The white matter of the spinal cord exhibits mild, multifocal vacuolation in the dorsal, lateral and ventral funiculi, within which are few Gitter cells containing myelin degradation products. Scattered, multifocal swollen axons (spherocytes) are present in the ventral and lateral funiculi. Variation in neuronal cytoplasmic staining is present with no loss of Nissl substance (decalcification artifact, presumptive). Surrounding epaxial skeletal muscles, and more prominently, muscle adjacent to the dorsal spinous process undergoes degeneration and regeneration, manifesting as myocyte size variation, sarcoplasmic hypereosinophila and vacuolation, loss of striation, satellitosis, central nuclei, and nuclear rowing.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

2. Cervical spinal cord: Focal compression with midline shift, mild, moderate Wallerian degeneration and spheroid formation.

3. Cervical skeletal muscles: Multifocal myodegeneration and regeneration.

4. Lung (caudal aspect left cranial lung lobe, not submitted): Multifocal chordoma metastasis.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Chordomas can occur anywhere along the axial skeleton. In the ferret, common sites include the tail tip (most common site), cervical vertebral column (second most common site), thoracic vertebral column, and the coccygeal region.1,4,6-12,14 The sacrococcygeal and spheno-occipital regions are the most common sites of chordoma occurrence in humans, with the remainder found in the vertebral axis.4,14 Up to 30% of human chordomas are reported to metastasize, typically during the phase of recurrent disease, with common sites of metastasis reported to be bone, lung, lymph node, skin and liver.1,4,14 Rare cases of local and distant skin metastases have been reported in the ferret.1,4,14 Vascular invasion was equivocal in the submitted section, however, was observed rarely in other sections of the mass and pulmonary metastases were present. One study evaluated cell proliferation indices in 5 ferret chordomas, and found that they were not predictive of metastatic potential.8

In humans, there are 3 recognized subtypes of chordoma: classic chordoma, chondroid chordoma, and chordoma with malignant spindle cell component (dedifferentiated). It has been suggested that ferret chordomas may act as an animal model for the chondroid subtype of human chordoma.4,14 Differentiation between classic and chondroid subtypes in humans is significant, as chondroid chordomas are associated with a survival rate 3 times greater than that of classic chordomas.1,8 Although the chondroid component was not prominent in the submitted section, it was more frequently observed in other sections of the mass.

Immunohistochemical analysis of chordomas in the ferret typically show dual expression of cytokeratin and vimentin, with variable expression of S-100 protein and neuron specific enolase (NSE).1,4,6-12,14 In one study of chordomas in 20 ferrets, 75% were positive for S-100 and 85% were positive for NSE.4 The S-100 positivity is thought to be due to glycosaminoglycan content within the stroma, and NSE is expressed in cells with high metabolic activity.1,4

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Aside from humans and ferrets, chordomas have been rarely reported in the axial skeleton of Fischer 344 rats11, mice13, dogs6,9, and cats2. In addition, 24 cases of spontaneous primary intestinal chordomas as well as nine spontaneous vertebral chordomas, were recently reported in the aged laboratory zebrafish3. In dogs, chordomas have been reported in the brain, spinal cord, and skin6. Of the three reported cases of feline chordoma, one was initially diagnosed as chronic granulomatous inflammation due to the interpretation of the characteristic physaliferous cells as atypical, foamy macrophages; it was subsequently dis-covered to be an example of a classic chordoma-like subtype, which then metastasized to multiple lymph nodes2.

In all species, chordomas tend to be slow growing and locally invasive.1-14 Typically, distant metastasis is associated with the classic chordoma and dedifferentiated spindle cell subtypes in humans, rather than the chondroid type which forms islands of cartilage and bone most commonly in the ferret and mink.1,4,8,10,14 In a large study of Fischer 344 rats there was an exceptionally high 75% incidence of pulmonary metastasis in animals diagnosed with chordomas.11 The histomorphology of chordomas in the Fischer rat is similar to the classic type in humans, which may explain the more aggressive biologic behavior in these rodents as compared to other animals.11 Prior to this case, visceral metastasis had not yet been reported in the ferret. However, the contributor recently published this case report, to include pulmonary metastasis via hematogenous spread; this is the first known case of visceral metastasis in the ferret5. The authors hypothesized that the metastatic potential in ferrets may increase over time, highlighting the importance of prompt surgical excision. Most cases of ferret chordomas occur at the tail tip making complete surgical excision relatively simple.1,4,5,14 Chordomas in other locations, such as this case, are substantially more difficult to excise.5

Chordomas in ferrets may histologically resemble chondrosarcomas due to the cartilaginous component. Conference participants briefly discussed immunohistochemistry as a method by which to differentiate chordoma from chondrosarcoma. As mentioned by the contributor, chordomas consistently demonstrate dual immunopositivity for vimentin and cytokeratin, while chon-drosarcomas are immunonegative for cytokeratin. Chordomas are also typically positive for S-100 and neuron-specific enolase (NSE); the S-100 and NSE positivity does not suggest neural crest origin, however.10,12 Other neoplasms of interest that typically express both vimentin and cytokeratin include: mesothelioma, synovial sarcoma, meningioma, renal cell carcinoma, adrenal carcinoma, and endometrial sarcoma.12

References:

2. Carpenter JL, Stein BS, King NW Jr, Dayal YD, Moore FM. Chordoma in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;197:240-242.

3. Cooper T, Murray K, et al. Primary intestinal and vertebral chordomas in laboratory zebrafish (Danio rerio). Vet Pathol. 2015;52(2):388-392.

4. Dunn DG, Harris RK, Meis JM, Sweet DE. A histomorphologic and immuneohistochemical study of chordoma in twenty ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Vet Pathol. 1991;28:467-473.

5. Frohlich J, Donovan T. Cervical chordomas in a domestic ferret (Mustela putorius furo) with pulmonary metastasis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2015;27(5)656-659. 6. Gruber A, Kneissi S, Vidoni B, Url A. Cervical spinal chordoma with chondromatous component in an dog. Vet Pathol. 2008;45(5):650653.

7. Koestner A, Bilzer T, Fatzer R, Schulman FY, Summers BA, Van Winkle TJ. Chordoma. In: Histological Classification of Tumors of the Nervous System of Domestic Animals, 2nd series, vol. V, pp. 36. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C., 1999.

8. Munday JS Brown CA, Richey LJ. Suspected metastatic coccygeal chordoma in a ferret (Mustela putorius furo). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2004;16(5):454-458.

9. Munday JS, Brown CA, Weiss R. Coccygeal chordoma in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2003;15(3):285-288.

10. Pye GW, Bennett RA, Roberts GD, Terrell SP. Thoracic vertebral chordoma in a domestic ferret (Mustela putorius furo). J Zoo Wildl Med 2000;31(1):107-111.

11. Stefanski SA, Elwell MR, Mitsumori K, Yoshitomi K, Dittrich K, Giles HD. Chordomas in Fischer 344 rats. Vet Pathol. 1988;25(1):42-47.

12. Takeshi Y, Tetsuo O, et al. Histochemical and immunohistochemical characterization of chordoma in ferrets. J Vet Med Sci. 2015;77(4):467-473.

13. Taylor, K, Garner M, et al. Chordomas at high prevalence in the captive population of the endangered Perdido Key Beach mouse (Peromyscus polinotus trissyllepsis). Vet Pathol. 2016;53(1):163-169.

14. Williams BH, Eighmy JJ, Berbert MH, Dunn DG. Cervical chordoma in two ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Vet Pathol. 1993;30:204-206.