Signalment:

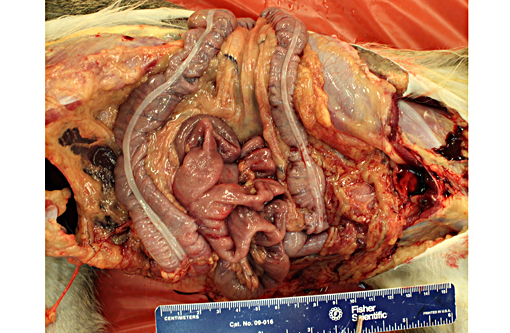

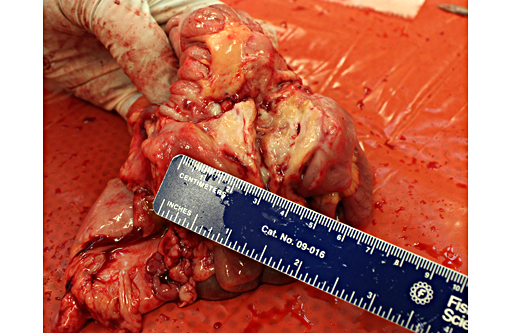

Gross Description:

A 4.5 cm x 1 mm tan nematode was present free within the stomach (Physaloptera sp, presumptive).

Embedded within the mucosa of the cecum were half a dozen tan nematodes, 4.5-5cm x0.5mm diameter with anterior filamentous ends (consistent with Trichuris sp).

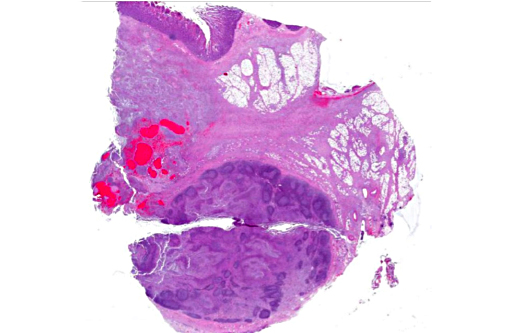

Histopathologic Description:

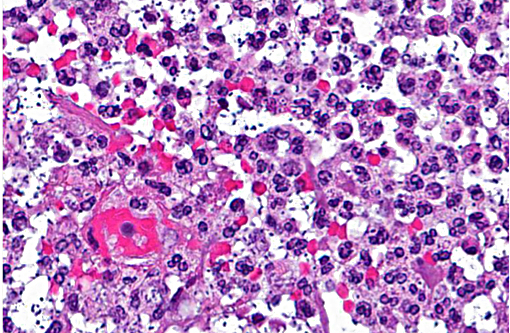

The intestinal mucosa is multifocally infiltrated by moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, with fewer eosinophils.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

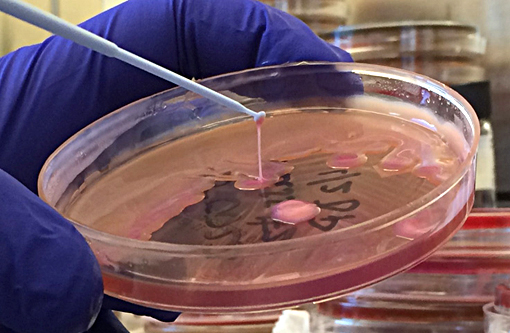

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a gram-negative, aerobic, nonmotile bacillus and is a common cause of a wide range of infections in humans and animals. In Old and New World monkeys, infection with K. pneumoniae causes pneumonia, meningitis, peritonitis, cystitis, and septicemia.(8) K. pneumoniae also constitutes normal fecal and oral flora in many nonhuman primates. In the past 2 decades, a new type of invasive K. pneumoniae disease has emerged in humans in Taiwan and other Asian countries, and more recently from non-Asian countries, including the USA.(4) Fatal human infections with invasive strains of K. pneumoniae involve pulmonary emboli or abscess, meningitis, endoph-thalmitis, osteomyelitis, or brain abscess.(4) Recently, a highly invasive K. pneumoniae causing primary liver abscesses in humans has also been reported.(5) These invasive, abscess-forming strains of K. pneumoniae are associated with the so-called hypermuco-viscosity (HMV) phenotype, a bacterial colony trait identified by a positive string test (>5mm string length).(3) These Klebsiella spp. generally develop prominent polysaccharide capsules which increase virulence by protecting the bacteria from phagocytosis and preventing destruction by bactericidal serum factors.

The HMV phenotype is seen in K. pneumoniae expressing either the capsular serotypes K1 or K2. K1 serotypes of K. pneumoniae have 2 potentially important genes, rmpA, a transcriptional activator of colanic acid biosynthesis, and magA, which encodes a 43-kD outer membrane protein. K2 serotypes of K. pneumoniae also have rmpA but do not have magA. Capsular serotypes K1 and K2 are reported to play an important role in the invasive ability of HMV K. pneumoniae. The role of rmpA and magA in the pathogenesis of invasive K. pneumonia, however, seems less certain.(11)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Two conference participants (co-authors on the Twenhafel et al. manuscript) referenced below, discussed in detail the events surrounding the cases described in that publication. At the time of that report, African green monkeys presenting initially with extensive mid-abdominal abscessation (and less commonly in other body systems), caused by hypermuco-viscosity K. pneumoniae was a novel finding.(10) Since, work has been done to characterize the hypermucoviscosity variant of K. pneumoniae as discussed in the contributors comment. The source of infection remains unclear and requires further epidemiologic studies. However, in at least one report in cohoused infected rhesus and cynomolgus macaques, transmission was thought to be fecal-oral and not from environmental contamination.(1) Like the source, the pathogenesis is still debatable particularly in light of extensive abscess formation in the mid-abdominal cavity in many cases. Participants discussed possible pathways to include septicemia or other methods of bacterial translocation from the intestine lumen. Regardless, the hypermucoid variant of K. pneumoniae is better able to resist innate immune defenses, including oxidative killing, and is more cytotoxic to blood monocytes in African green monkeys, compared to the non-hypermucoid variant, likely playing an important role in the pathogenesis.(2)

Conference participants also discussed infections caused by non-hypermucoviscosity K. pneumoniae in different animal species to include: Neonatal septicemia and pneumonia in foals and, abortion and stillbirth in mares;(6) mastitis in cattle; urinary tract infections in dogs; bronchopneumonia and polyserositis in guinea pigs; enterotyphlitis in rabbits; bacteremia, liver and kidney abscesses, pneumonia and myocarditis in mice; and abscesses in multiple locations in rats.(7)

References:

1. Burke RL, Whitehouse CA, Taylor JK, Selby EB. Epidemiology of Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae with Hypermu-coviscosity Phenotype in a Research Colony of Nonhuman Primates. Comp. Med. 2009;59(6):589-597.

2. Cox BL, Schiffer H, Dagget G Jr, et al. Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae to the innate immune system of African green monkeys. Vet Microbiol. 2015;176(1-2):134-42.

3. Fang CT, Chuang YP, Shun CT, et al. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J Exp Med. 2004;199: 697705.

4. Lau YJ, Hu BS, Wu WL, et al. Identification of a major cluster of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from patients with liver abscesses in Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol 2000;38(1):412-414.

5. Lederman ER, Crum NF. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: An emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(2):322-31.

6. Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, Elsevier; 2007:131,632.

7. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of laboratory rodents and rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell; 2007:64, 152, 229, 275.

8. Pisharath HR, Cooper TK, Brice AK, et al. Septicemia and Peritonitis in a colony of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. American association for laboratory animal science 2005;44(1): 35-37.

9. Ritter JM, Sanchez S, Jones TL, et al. Neurologic melioidosis in an imported pigtail macaque (Macaca nemestrina). Vet Pathol. 2013;50(6):1139-44.

10. Twenhafel NA, Whitehouse CA, Stevens EL, et al. Multisystemic abscesses in African green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops) with invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification of the hypermucoviscosity phenotype. Vet Pathol 2008;45:226231.

11. Yeh KM, Kurup A, Siu LK, et al. Capsular serotype K1 or K2, rather than magA and rmpA, is a major virulence determinant for Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in Singapore and Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:466471.