Signalment:

Gross Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

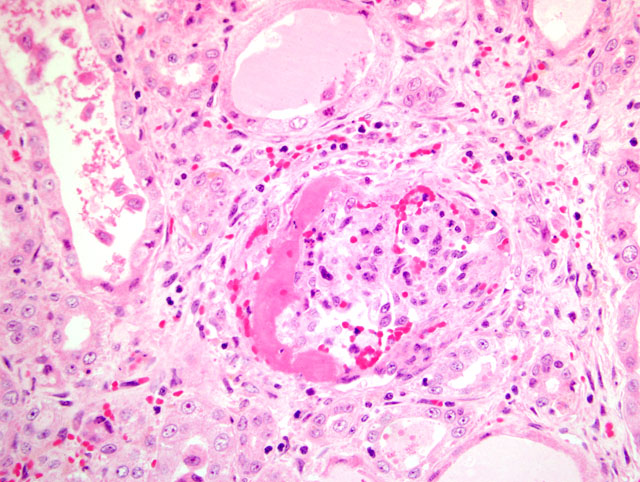

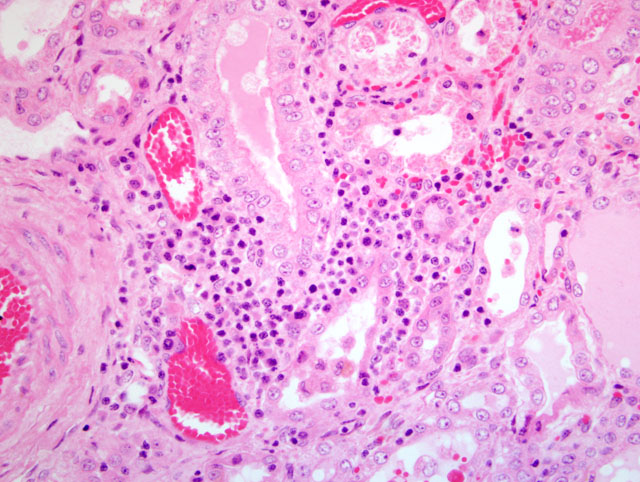

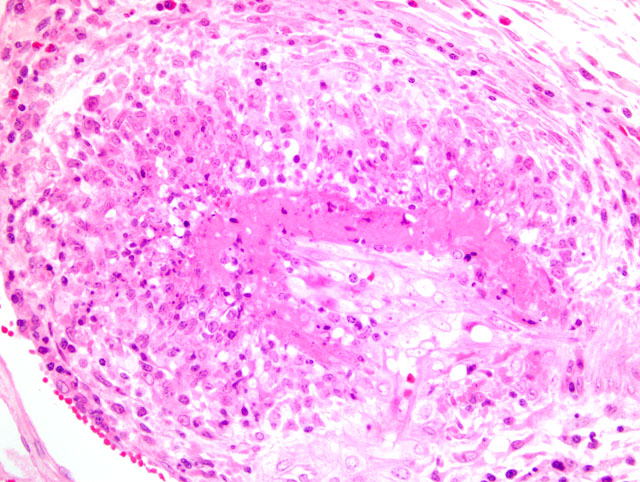

The most striking clinical signs of PDNS are necrotizing skin lesions due to necrotizing vasculitis. At necropsy, other frequent findings are enlarged and pale kidneys with cortical petechiae. Microscopically, these renal lesions vary from acute necrotizing glomerulitis to chronic glomerular sclerosis. Besides the skin lesions, systemic necrotizing vasculitis in a variety of organs has been observed.(7) As a possible pathogenetic mechanism for this disease a type III hypersensitivity reaction due to microscopic features has been suggested.(7)

The etiology still remains unknown, but porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) and Pasteurella multocida are discussed in the literature as possible contributing etiological agents.(8)

PDNS was first described in the United Kingdom in 1993.(9) Since then, several cases in Europe, North and South America and Africa have been described, suggesting a worldwide distribution.(7) This syndrome sometimes, but not always, occurs in commercial pig farms simultaneously with Postweaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome (PMWS). The relationship between the two syndromes is unclear.(7)

Differential diagnosis includes classical swine fever, African swine fever, swine erysipelas, and porcine stress syndrome. Bacterial diseases causing reddish discoloration of skin, petechiae, or cyanosis include infections by Actinobacillus suis, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Streptococcus suis, Haemophilus parasuis, and salmonellosis.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Kidney: Glomerulonephritis, exudative and membranoproliferative, diffuse, severe, with multifocal glomerular thrombosis and necrosis.

2. Kidney, arcuate arteries and branches: Arteritis, necrotizing and proliferative, diffuse, moderate to severe.

3. Kidney, pelvis: Epithelial hyperplasia and hypertrophy, diffuse, moderate, with marked cytoplasmic vacuolation.

Conference Comment:

In the United States, the incidence of PCV2-associated disease (PCVAD) is increasing. Clinically, PCVAD is characterized by one or more of the following manifestations: PMWS, PDNS, respiratory disease, enteritis, reproductive disease, myocarditis, vasculitis, and exudative dermatitis.(2,5) The preponderance of evidence suggests that PCV2 is essential, but not sufficient, for PCVAD development. Therefore, PCVAD can best be thought of as multifactorial, with such factors as the virus, host, cofactors, and immune modulation playing important roles in disease pathogenesis.

Circoviridae are small, single-stranded, circular DNA viruses. The Circoviridae family consists of the following genera: Gyrovirus, which contains chicken anemia virus as its sole member; the recently-discovered Anellovirus; and Circovirus. Along with PCV1 and PCV2, the Circovirus genus includes several avian circoviruses: beak and feather disease virus (BFDV), canary circovirus, goose circovirus, pigeon circovirus, duck circovirus, finch circovirus, and gull circovirus.(5,6) PCV1, which was initially discovered in tissue culture, is distributed worldwide and is nonpathogenic. PCV2 is very stable in the environment and has been found in wild boar in Germany and Spain, suggesting that they may be a reservoir.(6) PCV2 persists in dendritic cells, which are thought to serve as a vehicle for transport throughout the host.(5)

This case was submitted in 2004, and while there has been much work in the interim to further elucidate the cause and pathogenesis of PDNS, the role of PCV2 in the disease remains enigmatic and controversial. Numerous other etiologies, including PRRSV and a variety of bacteria have been proposed.(5) In one study, a high anti-PCV2 antibody titer was significantly associated with the development of PDNS, and PCV2 DNA was present in all PDNS cases; PPV and PRRSV nucleic acids were absent in many of the cases.(10) However, PDNS has not been experimentally reproduced in using PCV2, and PCV2 proteins are not detected in the vascular and glomerular lesions of PDNS.(4)

In a recent study, inoculation of gnotobiotic 2- and 3-day-old pigs with either of the following produced PDNS: 1) pooled plasma from healthy feeder pigs in a herd that was in the initial phases of a respiratory disease outbreak, and 2) a combination of PRRSV and tissue homogenate containing genogroup 1 torque teno virus (g1-TTV). All pigs seroconverted to PRRSV and were PCR-negative for PCV2; this was the first report of experimental induction of PDNS renal and cutaneous lesions in swine, and the authors concluded that PDNS is a manifestation of disseminated intravascular coagulation.(4) Interestingly, g1-TTV was also shown to potentiate PMWS in gnotobiotic pigs when inoculated together with PCV2. Disease was not produced by g1-TTV or PCV2 alone, or when PCV2-infected pigs were later challenged with g1-TTV.(3)

In addition to those listed by the contributor, other diseases that may mimic the skin lesions of PDNS include exudative epidermitis and swine pox. For the described gross renal lesions, i.e. turkey egg kidney, the differential diagnosis includes salmonellosis, African swine fever, and classical swine fever.(2) The cause and significance of the marked vacuolation of the epithelium lining the renal pelvis in this case is unclear.

References:

2. Chae C: A review of porcine circovirus 2-associated syndromes and diseases. Vet J 169:326-336, 2005

3. Ellis JA, Allan G, Krakowka S: Effect of coinfection with genogroup 1 porcine torque teno virus on porcine circovirus type 2associated postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in gnotobiotic pigs. Am Jour Vet Res 69(12):1608-1614, 2008

4. Krakowka S, Hartunian C, Hamberg A, Shoup D, Rings M, Zhang Y, Allan G, Ellis JA: Evaluation of induction of porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome in gnotobiotic pigs with negative results for porcine circovirus type 2. Am Jour Vet Res 69(12):1615-1622, 2008

5. Opriessnig T, Meng XJ, Halbur PG: Porcine Circovirus Type 2 associated disease: Update on current terminology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and intervention strategies. J Vet Diagn Invest 19:591-615, 2007

6. Radostits OM, Gay CC, Hinchcliff KW, Constable PD: Veterinary Medicine, A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, and Goats, 10th ed., pp. 1185-1193. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

7. Rosell C, Segal+â-¬s J, Ramos-Vara JA, Folch JM, Rodr+â-¡guez-Arrioja GM, Duran CO, Balasch M, Plana-Dur+â-ín J, Domingo M: Identification of porcine circovirus in tissues of pigs with porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome. Vet Rec 146:40-43, 2000

8. Segal+â-¬s J, Rosell C, Domingo M: Pathological findings associated with naturally acquired porcine circovirus type 2 associated disease. Vet Microbiol 98:137-149, 2004

9. Smith WJ, Thomson JR, Done S: Dermatitis nephropathy syndrome of pigs. Vet Rec 132:47, 1993

10. Wellenberg GJ, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, de Jong MF, Boersma WJ, Elbers AR: Excessive porcine circovirus type 2 antibody titres may trigger the development of porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome: a case-control study. Vet Microbiol 99:203-214, 2004