Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 9, Case 1

Signalment:

7-year-old female black and white colobus monkey (Colobus guereza).

History:

The animal was housed at a UK zoo collection as part of a colobus/patas monkey exhibit. It presented subdued and with reduced appetite; after a short period of clinical improvement the animal was found unable to move and was euthanized based on a poor prognosis. Previous appropriate fecal testing at a specialized laboratory was repeatedly positive for Entamoeba species for a period of 8 months prior to death. A male in the same group had also died in the past 5 months.

Gross Pathology:

The animal presented in poor body condition with no subcutaneous fat and widespread serous fat atrophy. Approximately 750ml of orange-yellow fluid were present in the abdominal cavity. The glandular portion of the stomach had a circular, 2cm diameter, slightly depressed, ulcer with a thin white and red halo (hyperemia). The liver showed a focal capsular adhesion to the gastric serosa. Cut surfaces displayed a diffusely enhanced lobular pattern and exhibited multifocal, dark yellow, 5mm to 5cm, nodular foci randomly distributed throughout the parenchyma. The right cranial lung lobe exhibited a focal, 4cm, mottled yellow-white and red nodule, with heterogeneously necrotic and mucopurulent cut surfaces. The middle right lung lobe was mottled red to dark-red and firm (consolidated). The left lung lobe had patchy areas of congestion. Remaining organs and body cavities were unremarkable on macroscopic examination.

Laboratory Results:

Clinical Pathology:

Liver, impression smear: Accumulations of degenerate neutrophils and vacuolated macrophages, including large central aggregations of densely cellular basophilic necrotic debris. Red blood cells and occasional multinucleated cells were present around the periphery of aggregates. A few normal hepatocytes were seen, with blue cytoplasm containing occasional dark blue/black granules (presumed hemosiderin). Mixed populations of bacteria were present amongst the cellular debris. Some areas had more abundant populations of spindle cells (presumptive fibroblasts).

Right lung, impression smear: Mixed populations of inflammatory cells including small numbers of degenerate neutrophils, abundant macrophages, and occasional multinucleated cells. Macrophages had vacuolated cytoplasm, sometimes with intracytoplasmic granular debris. Red blood cells were intermingled with inflammatory populations.

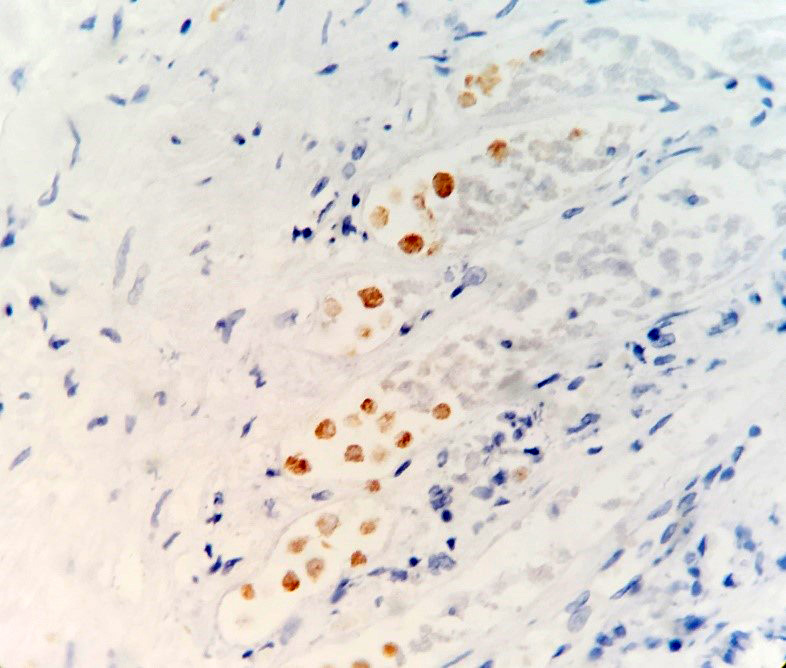

Immunohistochemistry:

IHC for E. histolytica: Positive (carried out at the Institute for Veterinary Pathology, University of Liverpool, following standard operating procedures).

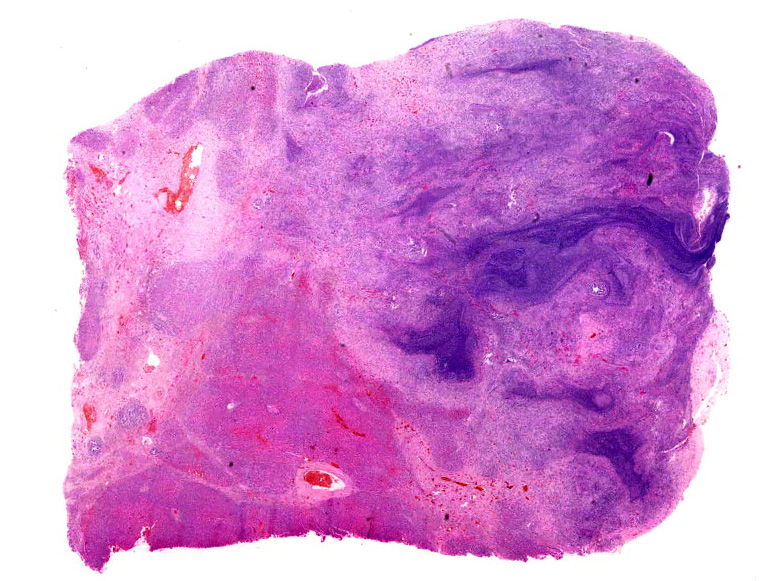

Microscopic Description:

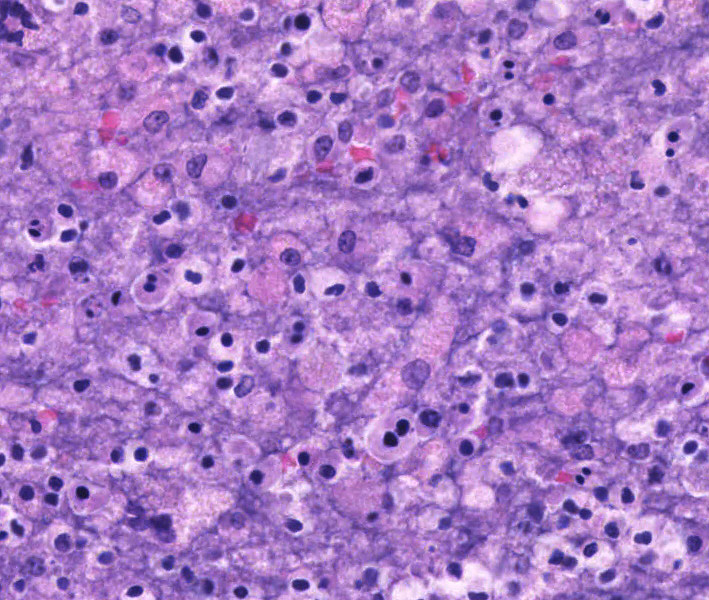

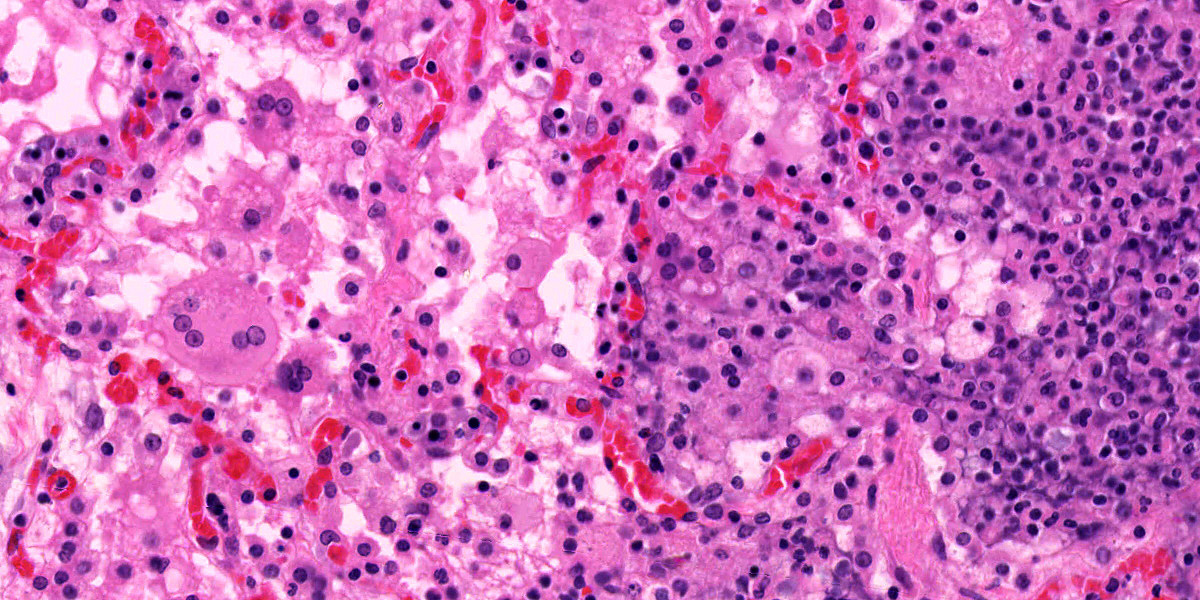

Liver: Randomly to bridging, approximately 80% of the examined section is completely effaced by multifocal to coalescent areas containing abundant amphophilic and basophilic amorphous debris (lytic necrosis) admixed with cytoclastic inflammatory cells, small numbers of viable and non-viable neutrophils, and moderate numbers of circular to oval, 15-20µm, unicellular protozoa with a pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with large phagocytic vacuoles and a pale small amphophilic eccentric basophilic round to oval nucleus (amoebic trophozoites). Areas of necrosis are intermingled and rimmed by numerous macrophages, neutrophils (viable and non-viable) and occasional multinucleated giant cells (Foreign body giant cell type) admixed with moderate deposition of reactive fibroblasts and mature collagen fibers (fibrosis). Interlacing and incorporating between the immature granulation and fibrotic tissue, there are myriad of irregular proliferated biliary ductules (biliary hyperplasia or ductular reaction). The adjacent parenchyma is composed of widely separated hepatic cords with small, irregular hepatocytes (atrophy).

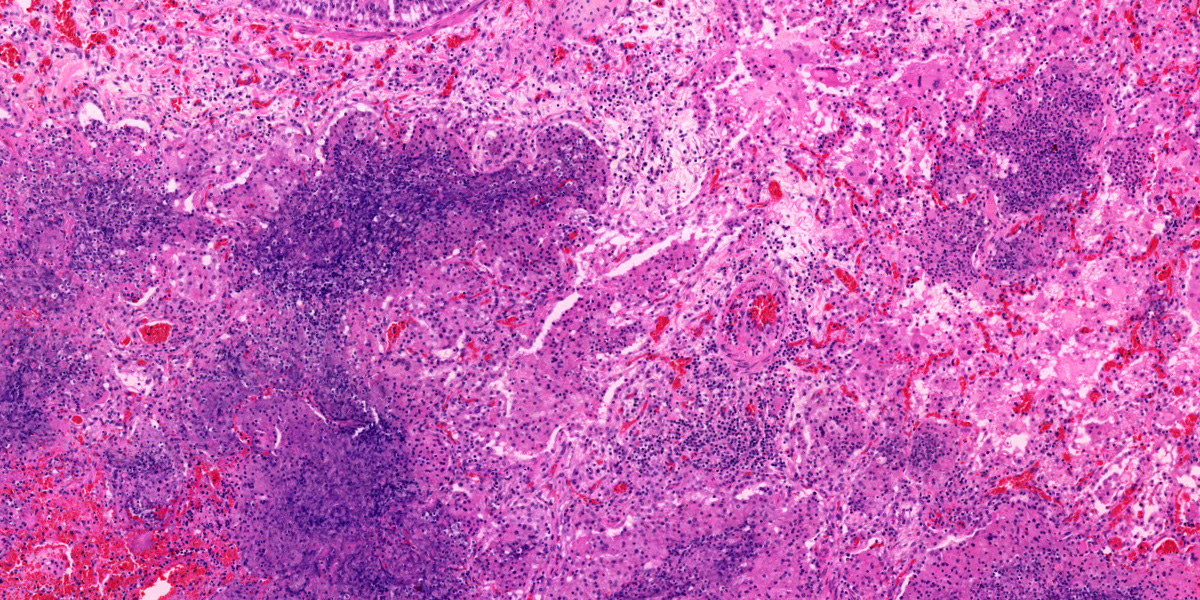

Lung: Multifocal to coalescing, affecting approximately 75% of the section, there is severe pyogranulomatous and necrotizing inflammation accompanied by large empty areas (cavitation of alveolar parenchyma) and dilated bronchi (bronchiectasis). Filling and expanding bronchi and bronchioles and effacing the adjacent pulmonary parenchyma, there are large numbers of amphophilic karyorrhectic and cellular debris (lytic necrosis), eosinophilic fibrillary beaded material (fibrin), viable and degenerated neutrophils, macrophages and extravasated erythrocytes (hemorrhage) admixed with orange/yellow hemoglobin breakdown pigments. Within the necrotic areas there are numerous circular or oval, 15-20µm, unicellular protozoa with a pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with large phagocytic vacuoles and pale small amphophilic eccentric round to oval nucleus (amoebic trophozoites). The necrotic areas are surrounded by abundant viable and degenerate neutrophils, macrophages (mostly epithelioid) and multinucleated giant cells (Langhans and foreign body type). Focally, there is a large thrombus filling a pulmonary vessel which is attached to the necrotic endothelium and composed of neutrophils, necrotic debris and fibrin. Multifocally, surrounding areas of inflammation, alveolar septa are expanded or effaced by increased collagen (fibrosis) and hypertrophic fibroblasts with perpendicularly arranged small blood vessels (granulation tissue). Adjacent septa are irregularly lined by cuboidal epithelium (pneumocyte type II hyperplasia). Less affected alveolar spaces are filled with a large amount of hemorrhage, occasionally admixed with fibrin, inflammatory debris and necrotic material. Multifocally, there are few discrete areas of pulmonary over inflation.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Hepatitis, necrotizing, pyogranulomatous, fibrosing, with abundant intralesional protozoal (amoebic) trophozoites consistent with Entamoeba spp., and bile duct hyperplasia, severe, multifocal to coalescent, random to bridging), chronic-active; liver.

2. Pneumonia, necrotizing, pyogranulomatous, with bronchiectasis, fibrin thrombus, and intralesional protozoal (amoebic) trophozoites consistent with Entamoeba spp., severe, multifocal to coalescent, chronic-active; lung.

Contributor’s Comment:

Lesions in this case were consistent with chronic-active hepatic and pulmonary amebiasis. Other concomitant lesions in this case included ulcerative amebic gastritis, ascites, and emaciation. Unicellular protozoal organisms whose morphology were consistent with Entamoeba spp. were observed within the necrotic areas in the liver, lung, and stomach. Immunohistochemistry for Entamoeba histolytica was positive, further confirming the histopathological diagnosis.

E. histolytica is a protozoan parasite reported worldwide to occur in humans and a wide range of New and Old World monkeys, as well as apes.8 Several species have been described which differ in their location in the host and nonhuman primate (NHP) species affected including E. histolytica, E. dispar, E. moshkovskii, E. polecki, E. nutalli, E. chattoni, E. coli, E. hartmanni, E. ecuadoriensis and E. bangladeshi.8 In the United Kingdom, one study suggests a notable prevalence of Entamoeba infection in NHPs with three main species circulating in the zoo’s environment, namely E. histolytica, E. dispar and E. polecki ST4.6

Included under the E. histolytica species complex are E. histolytica, E. dispar and E. moshkovskii. They have different virulence capabilities, but are morphologically indistinguishable.7 E. histolytica is the most commonly recognized zoonotic agent and can cause both intra- and extraintestinal disease.1,8 There is a zoonotic risk for humans in close contact with primates.6 The pathogenicity is determined by multiple virulence factors such as ubiquitin and adhesive surface lectins and is further depend on strain, host species, nutritional status, gastrointestinal (GI) microflora, environmental factors.1,2,8 The essential steps leading to tissue damage are the adhesion of the organism to the hosts’ protective mucus by lectin followed by enzymatic mucus breakdown and lectin-mediated adherence to host epithelium. Damage to mucosal epithelium is mediated by the release of cysteine proteases that attract inflammatory cells.

Usually, clinical signs are unspecific and NHPs show lethargy, weakness apathy, dehydration, anorexia, vomiting, rectal prolapse and severe catarrhal or hemorrhagic diarrhea.1,8

Fatal amebiasis with abscess formation particularly in the liver and more infrequently in the lung and the brain is reported in humans, colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza; Colobus abyssinicus), douc langurs (Pygathrix nemaeus), dusky leaf monkeys (Presbytis obscurus), chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), baboons (Papio spp.), orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), and spider monkeys (Ateles spp.).1,6,8,9 Concurrent amebic gastritis is predominantly seen in leaf-eating primates (colobus monkey, silver-leafed monkey) and other gastric fermenting folivores such as langurs and proboscis and relates to higher stomach pH that is conducive to survival of ameba.1,9

The encystment of the infective forms appears to take place in the small intestine and the infection is established in the lumen of the large intestine. Infections are often transient and self-limiting. Under certain circumstances however, E. histolytica may invade the intestinal wall and cause colitis and consecutive amebic hepatitis by spread via the portal vein.9 Hematogenous and/or lymphatic invasion of other organs (brain, lung) is rare and reported to be nearly always associated with liver abscesses.8

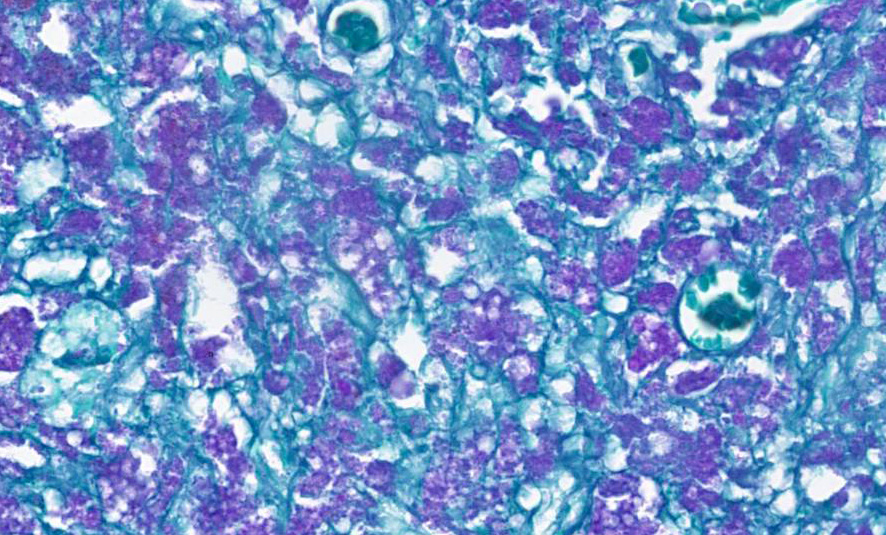

Microscopically, amebae are surrounded by a clear halo with extensive pseudopodia and possess a nucleus with a dark karyosome. The cytoplasm appears foamy and they frequently phagocytize erythrocytes, which makes them difficult to distinguish from activated macrophages. The periodic acid-Schiff reaction highlights intracytoplasmic glycogen granules within amebae. Trichrome and Giemsa stains can also be utilized to emphasize amoebic trophozoites. On direct smears, Lugol’s iodine can be used to aid the diagnosis of trophozoites, due to the presence of intracytoplasmic glycogen (starch).

Contributing Institution:

International Zoo Veterinary Group, Station House, Parkwood Street, Keighley, BD21 4NQ, UK. Website: www.izvg.co.uk

JPC Diagnosis:

- Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, chronic-active, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with numerous amebic trophozoites.

- Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, necro-hemorrhagic, chronic-active, diffuse, severe, with pleural granulation tissue and numerous amebic trophozoites.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Dr. Jeremy Bearss, previous chairman of the department and current research pathologist with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This week’s cases were chosen as they are all excellent “descriptive cases”.

The profoundly necrotizing nature of these lesions was evident from low magnification, although more careful observation was required to pick up evidence of chronicity including type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, fibrosis, and subpleural granulation tissue within the lung and nodular regeneration and biliary hyperplasia within the liver. Although amebae were recognizable in large numbers on H&E, both PAS and GMS stains were helpful in highlighting them, and are consoiderations for cases in whichch their numbers are reduced.

As the contributor notes, diet plays a role in the pathogenesis of this entity in leaf-eating primates. Colobine monkeys have a large simple stomach with four compartments, which provide dedicated space for increased fermentation.3 The relative increase in pH in this portion of the stomach is conducive to the survival of ameba. The gastric ulcers noted in the clinical history are the portal of entry of Entamoeba into the portal system with dissemination to liver and lungs. Dr. Kali Holder (Smithsonian conservation pathologist) was among conference attendees and noted that similar Entamoeba lesions can be seen in kangaroos and wallabies given their similar diet and compartmented stomach structure.

Finally, the role of Entamoeba as both a zoonosis and anthrozoonosis is worth considering. Transmission of Entamoeba from captive non-human primates to caretakers was previously described.5 E. nuttalli is pathogenic in animals, though its role in human disease is unclear. Nonetheless, caretakers that did not care for NHPs lacked the presence of E. nuttalli in fecal specimens, consistent with transmission of the agent within the zoo environment. Conversely, potential transmission of E. histolytica from humans to chimpanzees and baboons in the Gombe region of Tanzania has also been detailed.4

References:

- Calle P, Joslin J. Chapter 37 - New World and Old World monkeys. In: Miller R, Fowler M, eds. Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine, Volume 8. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Inc.; 2015:301–335.

- Crisóstomo-Vázquez MDP, Jiménez-Cardoso E, Arroyave-Hernández C. Entamoeba histolytica sequences and their relationship with experimental liver abscesses in hamsters. Parasitol Res. 2006;98:94–98.

- Davies G, Oates J. Colobine Monkeys: Their Ecology, Behaviour and Evolution. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 205-284.

- Deere JR, Parsons MB, Lonsdorf EV, et al. Entamoeba histolytica infection in humans, chimpanzees and baboons in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania. Parasitology. 2019;146(9):1116-1122.

- Levecke B, Dorny P, Vercammen F, et al. Transmission of Entamoeba nuttalli and Trichuris trichiura from Nonhuman Primates to Humans. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2015;21(10):1871-1872.

- Regan CS, Yon L, Hossain M, Elsheikha HM. Prevalence of Entamoeba species in captive primates in zoological gardens in the UK. PeerJ. 2014;DOI 10.7717/peerj.492.

- Sargeaunt P, Williams JE, Jones DM. Electrophoretic Isoenzyme Patterns of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba chattoni in a Primate Survey. J Protozool. 1982;29:136–139.

- Strait K, Else J, Eberhard M. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases, Vol.2. London: Elsevier Inc.; 2012:197–297.

- Ulrich R, Böer M, Herder V, et al. Epizootic fatal amebiasis in an outdoor group of Old World monkeys. J Med Primatol. 2010;39:160–165.