WSC 2023-2024, Conference 18, Case 2

Signalment:

Adult male black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus)

History:

A dead black-tailed jackrabbit without signs of predation was found by a private citizen that was falcon hunting in southern California.

Gross Pathology:

The carcass was in a mild to moderate state of postmortem decomposition and poor nutritional condition. There was a moderate amount of serosanguineous fluid in the thorax. The lungs were pink to red, swollen, and wet. The liver was dark-red, congested, and oozed dark-red fluid on cut surface.

Laboratory Results:

RHDV2 RT-qPCR: Positive (Ct 11.8).

Pan-lagovirus IHC in liver (antibodies provided by Drs. Lavazza and Capucci, IZSLER, Italy): Positive.

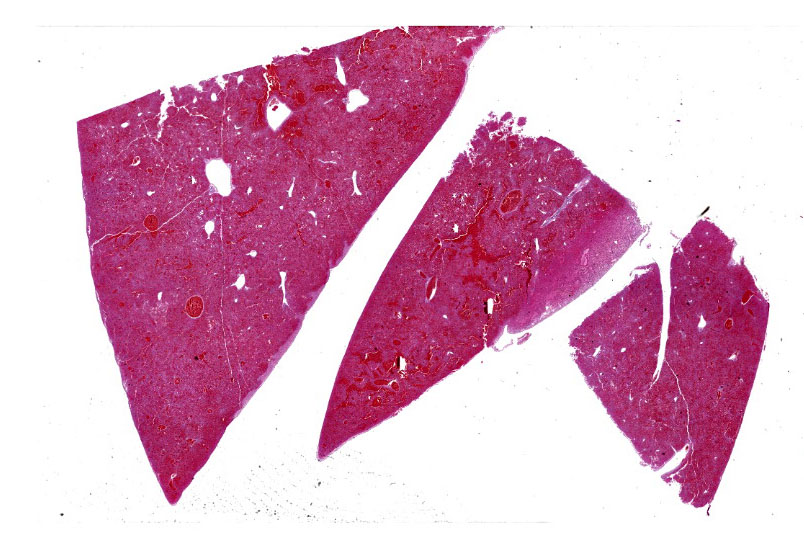

Microscopic Description:

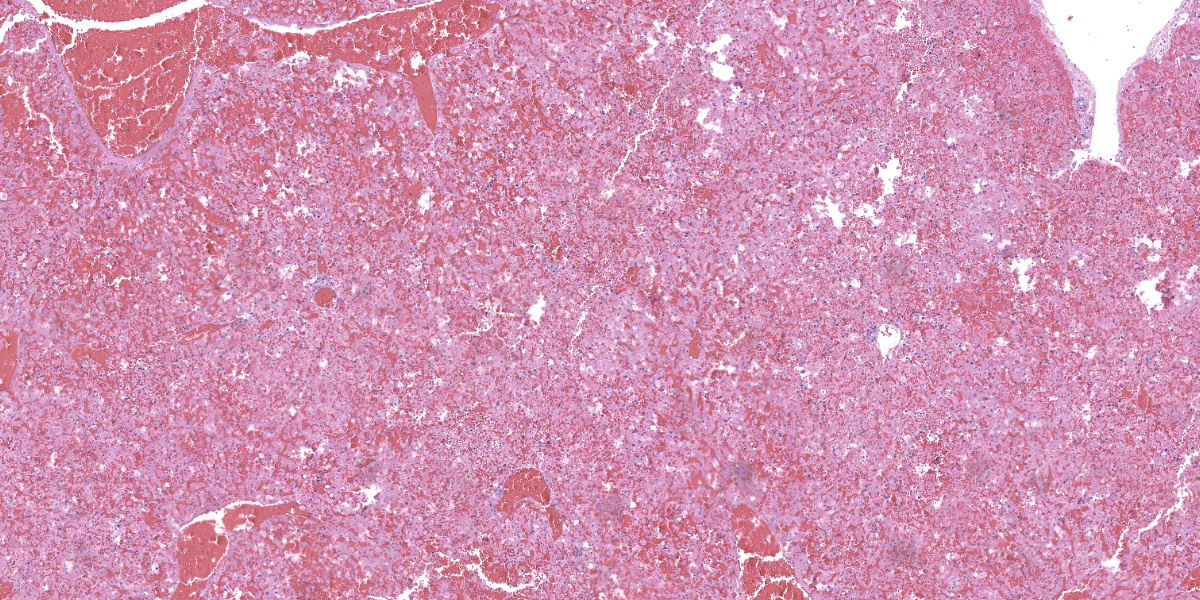

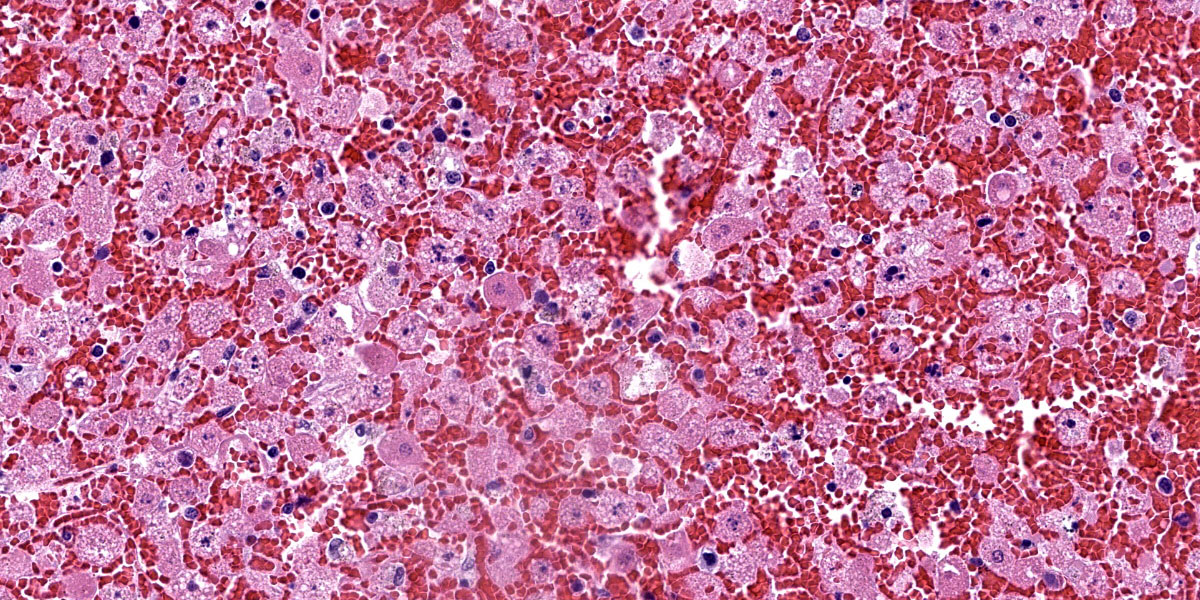

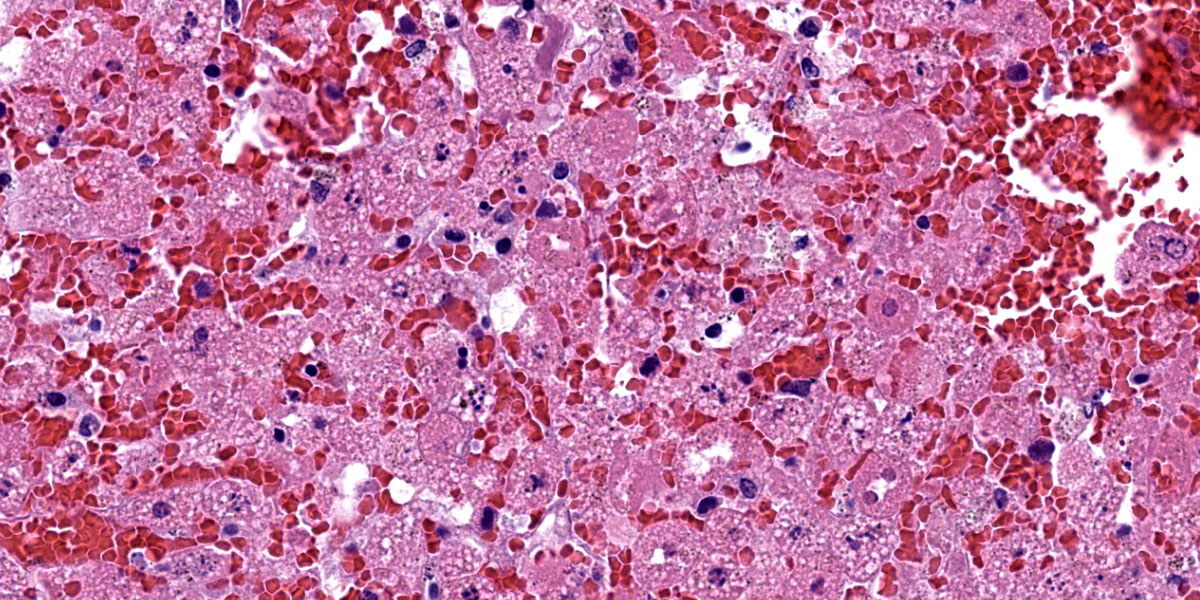

Liver: There is diffuse, periportal to panlobular hyperosinophilia with disorganization of hepatic cords (necrosis) and abundant hemorrhage and congestion. Hepatocytes show one or more of the following changes: membrane and cytoplasmic fragmentation, pyknosis, karyorrhexis, and occasional individual mineralization. There are rare, scattered heteorophils, and mild infiltrates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in the portal spaces, as well as some subscapular follicular aggregates of lymphocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver, necrosis, panlobular, severe, acute with hemorrhage

Contributor’s Comment:

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus type 2 (RHDV2 or GI.2) belongs to the genus Lagovirus, a group of viruses within the family Caliciviridae that affects species in the order Lagomorpha.5 This virus was detected for the first time in France in 2010 and has been spreading among domestic and wild leporid species in North America since 2020.7,11 A distinctive feature of RHDV2 is its host range, which is wider than that of its close relative, classic RHDV (or GI.1); the latter affects principally domestic and wild European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), whereas RHDV2 affects also several hare and jackrabbit species (Lepus spp.), as well as cottontails and other wild rabbits native to the American continent (Sylvilagus spp.).11 RHDV2 is broadening its host range as it spreads and new leporid species are exposed to it for the first time.

In domestic rabbits, classic RHD is associated with high mortality; animals generally succumb after a short period of fever, lethargy, seizures and bleeding through body orifices.1 Hepatomegaly with pallor and reticular pattern, pulmonary congestion with hemorrhages, splenomegaly, hemorrhages in multiple tissues, and icterus are the most common gross findings. Histologically, there is periportal to panlobular hepatic necrosis, splenic red pulp necrosis and lymphoid depletion, and systemic thrombosis in small capillaries (e.g., in renal glomeruli and pulmonary septae).

RHDV2 seems to cause similar clinical signs and lesions, although possibly with more variable mortality according to some reports.7,10 Specifically in hares (Lepus spp.), RHDV2 causes a disease process similar to RHD in rabbits or to the European brown hare syndrome (caused by another Lagovirus, EBHSV or GII) in several hare species from Europe.4 Clinicopathologic data of RHDV2 infection in hares is limited to just a few studies that would suggest that mortality is lower and more variable than in rabbits.4,12

Data on the pathology of RHDV2 on North American leporid species is very limited. An experimental study confirmed for the first time that that the eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) was susceptible to RHDV2 and developed a similar disease process as observed in New Zealand white rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus).9 According to one of the first reports of natural disease in cases from early 2020 in the USA, the pathology of RHDV2 in desert cottontails (Sylvilagus audubonii) and black-tailed jackrabbits (Lepus californicus) is similar to previous descriptions in wild and domestic European rabbits and other hare species, with hepatic necrosis as the most diagnostically relevant finding; however, glomerular or pulmonary fibrin thrombi and splenic necrosis were not identified in the animals of the mentioned report, which differs with previous descriptions of RHDV2 in rabbits of European origin.6

In California, RHDV2 was confirmed for the first time in a black-tailed jackrabbit on May 2020 as part of an outbreak that was spreading throughout the southwest at that time.2 The disease spread quickly among multiple southern counties of the state between 2020 and 2021, and was later detected in northern areas as well. Domestic rabbits (including pets, backyard rabbitries, and a few commercial farms), black-tailed jackrabbits, desert cottontails, Western brush rabbits (Sylvilagus bachmani) and its endangered subspecies, the Riparian brush rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani riparius), have been affected by RHDV2 in California. Some of the early circulating viruses in the south of the state were phylogenetically similar to other detections in Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico earlier in 2020. Among all the detections of RHVD2 in North America since the first cases in Quebec, Canada, in 2016, the early California sequences were more similar to a virus collected in British Columbia, Canada, in 2018.3

Contributing Institution:

California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory System (CAHFS)

University of California-Davis

San Bernardino, California

https://cahfs.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/locations/san-bernardino-lab

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, acute, massive, diffuse, severe, with hemorrhage.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent overview of the biology, natural history, and unfortunate spread of RHDV2. The spread of RHDV2 is concerning not only for native susceptible lagomorph species, but also for the predators which depend on them for a food source. RHDV2 can profoundly alter the ecosystems in which it is introduced as evidenced by the emergence of RHDV2 on the Iberian Peninsula in 2013. In that outbreak, the wild rabbit population of northern Spain declined precipitously; unfortunately, population numbers for the Iberian lynx and the Spanish eagle, both endanged species that rely heavily on rabbit-based diets, declined in tandem.3 This scenario has repeated with each introduction of RHDV2 into a new ecosystem and is particularly instructive for the current outbreak in California, as the state has established populations of mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, and golden eagles that also make rabbit a staple of their diets.3

Until recently, prevention measures have been confined to biosecurity and husbandry practices such as handwashing, quarantining animals, disinfectants, and limiting contact with animals. These efforts have been generally unsuccessful in slowing the unrelenting spread of the virus due to RHDV’s multiple routes of transmission; the virus can be spread mechanically by flies and other vectors, by fomites, and by infected carcasses which can harbor communicable virus for up to three months.4 The primary route of transmission is oral, though nasal, subcutaneous, intravenous, and intramuscular transmission has been identified.4 Wildlife researchers and rabbit hobbyists alike were cheered in 2021, when the USDA gave Emergency Use Authorization to a US-based RHDV2 vaccine; the vaccine was given a Conditional Use license in November 2023, providing a new weapon in the fight against this fatal, emerging disease.8

The hallmark of RHDV2 is massive hepatocellular necrosis as abundantly illustrated by this case. Conference participants remarked on the incredible degree of hepatocellular destruction, the abundant hemorrhage that separated and surrounded the remnant hepatocytes, and the general lack of associated inflammation. Conference participants also considered a reticulin stain which showed complete loss of sinusoidal architecture, confirming the tissue destruction evident on H&E. The moderator noted that it would be easy to focus on the astonishing amount of hemorrhage and destruction and overlook the finer descriptive points of nuclear features (karyorrhexis, karyolysis), type and extent of necrosis, and the mineralization noted occasionally throughout the section.

Conference participants noted the vacuolar changes in the hepatocytes and debated whether these were lipid-type or glycogen-type changes. Participants decided that the vacuoles were likely neither, but instead represented swelling of the endoplasmic reticulum during cellular necrosis. The moderator called attention to the eosinophilic globules present throughout the section, called acidophilic or “Councilman bodies.” Councilman bodies are aggregated apoptotic hepatocyte fragments that are observed in viral hepatitides and are named after American pathologist William Thomas Councilman who discovered them during his work on yellow fever. Finally, participants discussed lung lobe torsion, a differential common in rabbits, which would appear as a whole-lobe coagulative necrosis with retention of hepatocellular architecture, quite different from the impressive lytic necrosis present in this slide.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis was fairly straightforward in this case, though not without minor drama. One particularly insistent conference participant argued for the inclusion of hemorrhage in the morphologic diagnosis due to the prominence of this feature in the disease itself and on the examined slide. Dissenting voices argued that necrosis implies hemorrhage, making its inclusion redudant; however, persistence carried the day and hemorrhage won by a hare.

References:

- Abrantes J, van der Loo W, Le Pendu J, et al. Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV): a review. Vet Res. 2012;43(1): 12.

- Asin J, Nyaoke AC, Moore JD, et al. Outbreak of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 in the southwestern United States: first detections in southern California. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2021;33(4):728-731.

- Asin J, Rejmanek D, Clifford DL, et al. Early circulation of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus type 2 in domestic and wild lagomorphs in southern California, USA (2020-2021). Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69(4):e394-e405.

- Byrne AW, Marnell F, Barrett D, et al. Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus 2 (RHDV2; GI.2) in Ireland Focusing on Wild Irish Hares (Lepus timidus hibernicus): An Overview of the First Outbreaks and Contextual Review. Pathogens. 2022; 11(3):288.

- Capucci L, Cavadini P, Lavazza A. Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus and European brown hare syndrome virus. In: Bamford DH, Zuckerman M, eds. Encyclopedia of Virology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. pp. Academic Press, Elsevier; 2021:724-729.

- Lankton JS, Knowles S, Keller S, Shearn-Bochsler VI, Ip HS. Pathology of Lagovirus europaeus GI.2/RHDV2/b (Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2) in Native North American Lagomorphs. J Wildl Dis. 2021;57(3):694-700.

- Le Gall-Reculé G, Lavazza A, Marchandeau S, et al. Emergence of a new lagovirus related to Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus. Vet Res. 2013;44(1):81.

- “Medgene’s RHDV2 vaccine granted critical license of USDA’s center for veterinary biologics.” Nov 2, 2023. Available at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/medgenes-rhdv2-vaccine-granted-critical-license-by-usdas-center-for-veterinary-biologics-301974936.html.

- Mohamed F, Gidlewski T, Berninger ML, et al. Comparative susceptibility of eastern cottontails and New Zealand white rabbits to classical rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) and RHDV2. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69(4):e968-978.

- Neimanis A, Larsson Pettersson U, Huang N, et al. Elucidation of the pathology and tissue distribution of Lagovirus europaeus GI.2/RHDV2 (rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus 2) in young and adult rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Vet Res. 2018;49(1):46.

- Shapiro HG, Pienaar EF, Kohl MT. Barriers to management of a foreign animal disease at the wildlife-domestic animal interface: the case of rabbit hemorrhagic disease in the United States. Front Conserv Sci. 2022;3:857678.

- Velarde R, Cavadini P, Neimanis A, et al. Spillover events of infection of brown hares (Lepus europaeus) with Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Type 2 Virus (RHDV2) caused sporadic cases of an European brown hare syndrome-like disease in Italy and Spain. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64(6):1750-1761.