Signalment:

Gross Description:

Macroscopically, the mid-region of the uterine mucosa of both horns was multifocally and segmentally expanded by a few, nodular, firm masses. There was one mass in the right uterine horn (3.0 x 2.5 x 1.5 cm, partially bisected by submitter) and two smaller masses in the left uterine horn (1.8 cm and 1.5 cm diameter), all of which oozed moderate amounts of clear fluid on sectioning.

Histopathologic Description:

The mucosa distal and proximal to the uterine masses described above contained pools of erythrocytes, and endometrial glands were nested and separated by moderate amounts of collagenous stroma. Luminal epithelium was tall columnar with plump cytoplasm containing numerous cytoplasmic vacuoles.

Ovaries: In two cross-bisected sections, approximately 40 to 60% of the right and left ovaries were composed of large corpora lutea. The remaining portions of the ovaries had follicles in various developmental stages.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Uterus: Segmental endometrial hyperplasia (pseudo-placentational endometrial hyperplasia).

2. Ovary: Multiple ovarian corpora lutea.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In females of most domestic species (especially mares, sows and cows), the pathologic condition of endometrial hyperplasia is associated with hyperestrogenism.(8) Endogenous estrogen from cystic follicles or granulosa cell tumors and ingestion of exogenous estrogenic plants have been implicated. In the bitch and the queen, the condition usually referred to as cystic endometrial hyperplasia (CEH)-pyometra complex has been attributed to diffuse cystic proliferation of endometrial glands under prolonged progesterone influence after estrogen priming. Although some authors have argued that CEH and pyometra are not necessarily linked,(1) it is generally accepted that the same prolonged high progesterone levels that cause endometrial gland proliferation also increase susceptibility of the uterus to infection.(3) Besides the CEH-pyometra complex, McKentee described 3 other forms of endometrial hyperplasia in the bitch: 1) estrogen-induced CEH, 2) focal endometrial polyps and 3) endometrial hyperplasia associated with psuedopregnancy; the latter is the subject of this report.

Segmental endometrial hyperplasia, also called pseudo-placentational endometrial hyperplasia (PEH) and deciduoma, is a condition of the canine uterus not always associated with psuedopregnancy.(2,7) Although the cause of spontaneous cases is unknown, the condition has been induced by intraluminal stimulation of the canine uterus in the luteal phase of the estrous cycle.(5,6) Clinically it has been associated, along with CEH and endometritis, with infertility and pregnancy loss in the bitch.(4) The term -�-�deciduoma as used by some authors is derived from conditions in primates and rodents and is less accurate in that it implies a neoplastic rather than hyperplastic lesion.(9)

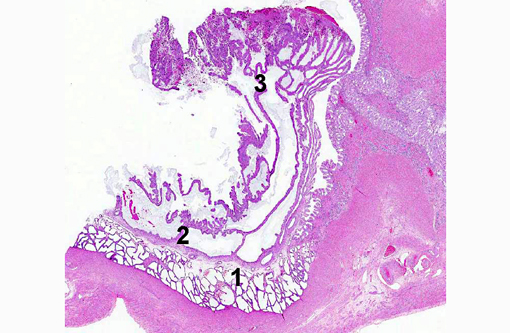

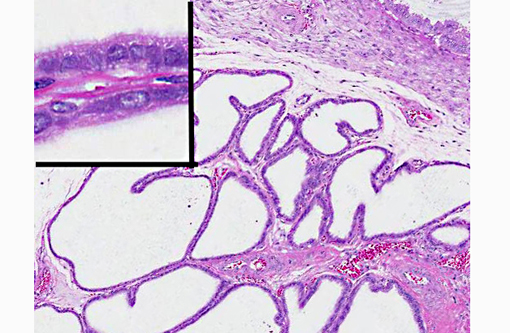

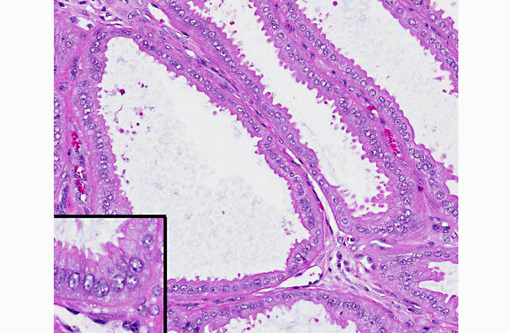

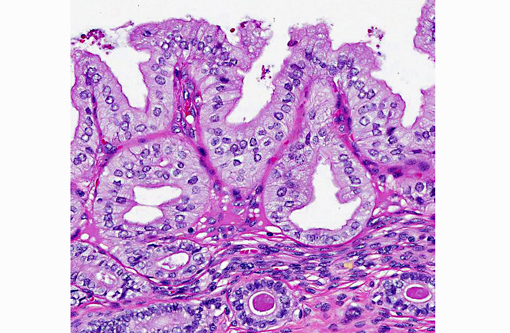

PEH is clearly distinguishable from CEH both grossly and histologically.(9) While CEH is generally a diffuse reaction involving the entire endometrium, PEH is a characterized by focal or multifocal masses mimicking placentation sites. Histologically, the masses are characterized by the 3 distinct zones mimicking the normal maternal placenta.(2) The deepest, outermost zone, also called the stratum spongiosum, is composed of dilated glandular structures. That zone is separated from the highly folded luminal epithelium by a dense connective tissue band. The luminal surface consists of pseudostratified epithelium with scattered necrotic syncytia formation; fetal remnants and membranes are not identified.(9)

McKentee described regression of similar lesions in cases of psuedocyesis,(3) presumably as a result of falling progesterone levels. In a study of infertility in bitches, PEH was identified by uterine biopsy at various stages of the estrous cycle, but hormone levels were not recorded.(4) In the case of the young bitch in this report, presence of multiple corpora lutea in the ovaries at the time of ovariohysterectomy suggests that the lesions formed or at least were maintained in the presence of high circulating progesterone; whether the lesions would have regressed as CLs regressed is unknown. The fact that the dog had documented infertility, however, suggests the PEH may have been interfering with fertility in this case.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

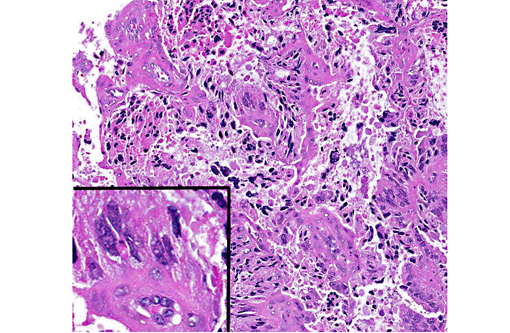

Dr. Robert Foster of the University of Guelph was consulted on this possible interpretation. Dr. Foster confirmed that the presence of syncytia in the outermost layer is an expected finding in PEH, and the lack of multinucleated cells within deeper layers argues against the possibility that they are true syncytiotrophoblasts.

In this case, the corpora lutea are considered essentially normal, the cellular atypia seen within the largest nodule is considered to be within acceptable morphologic limits. In the area of the endometrium adjacent to PEH, the progestational effects (vacuolation of endometrial cells, tortuosity of glands, and presence of secretory material within deep glands) of these corpora lutea is seen.

References:

2. Koguchi A, Nomura K, Fujiwara T, et al. Maternal placenta-like endometrial hyperplasia in a Beagle dog (canine deciduoma). Exp Anim. 1995;44:251-253.

3. McKentee K. The uterus: atrophic, metaplastic and proliferative lesions. In: Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Animals. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 199:171-175.

4. Mir F, Fontaine E, Albaric O, et al. Findings in uterine biopsies obtained by laparotomy from bitches with unexplained infertility or pregnancy loss: an observational study. Theriogenol. 2013;79:312-322.

5. Nomura K. Induction of canine deciduoma in some reproductive stages with different conditions of the corpora lutea. J Vet Med Sci. 1997;59:185-190.

6. Nomura K, Makino T. Effect of ovariectomy in the early first half of the diestrus on induction or maintenance of canine deciduoma. J Vet Med Sci. 1997;59:227-230.

7. Sato Y. Psuedo-placentational endometrial hyperplasia in a dog. J Vet Diag Invest. 2011;23:1071-1074.

8. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Pathology of the genital system of the nongravid female. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsiever; 2007:462-463.

9. Schlafer DH, Gifford AT. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia, psuedoplacentational endometrial hyperplasia and other cystic conditions of the canine and feline uterus. Theriogenol. 2008;70:349-358.