Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 2

28 August, 2019

CASE I: Case #2 (JPC 4117378).

Signalment: 9-year-old, male, African lion (Panthera leo).

History: Caesar was born in June 2007. He and his sister, Cleopatra, were purchased from a breeder in Louisiana by a man who lives in Austin and had a large ranch in the northern Hill Country. The owner contacted the Austin Zoo and Animal Sanctuary in spring 2009 wanting to surrender the pair as he could not get a permit from the county to keep them. Caesar and Cleopatra arrived at the Austin Zoo and Animal Sanctuary in May 2009. Cleopatra got sick in spring 2011 and was humanely euthanized in July 2011 after she was diagnosed with canine distemper virus (CDV) and developed seizure activity. Caesar had never shown any symptoms at this time. All of the large felids were vaccinated for CDV shortly after Cleopatra died. Caesar had a diminished appetite in December 2013 and started exhibiting unusual behavior (e.g. jumping around the walls of his den). His appetite returned in January 2014, but he became ataxic in March 2014. The ataxia became progressively worse until he was no longer able to get his feet under him to walk up the steps into his den. He was admitted to the Texas A&M CVM for examination. He had a high positive titer for toxoplasmosis and a low positive titer for CDV which was thought to be a result of his vaccination. He was alert with an excellent appetite while being treated for toxoplasmosis. After some instances of apparent improvement, he ultimately started star gazing, stopped eating and became nonresponsive, at which time he was humanely euthanized.

Gross Pathology: Patient is emaciated (BCS 2/9). There are multiple, red, inflamed areas on skin from trauma and pressure sores. There is an abscess in the ventral neck associated with the right mandibular lymph node. The brain appears slightly shrunken. No other significant gross lesions are observed.

Laboratory results: Brain, positive for CDV by IHC.

Microscopic Description:

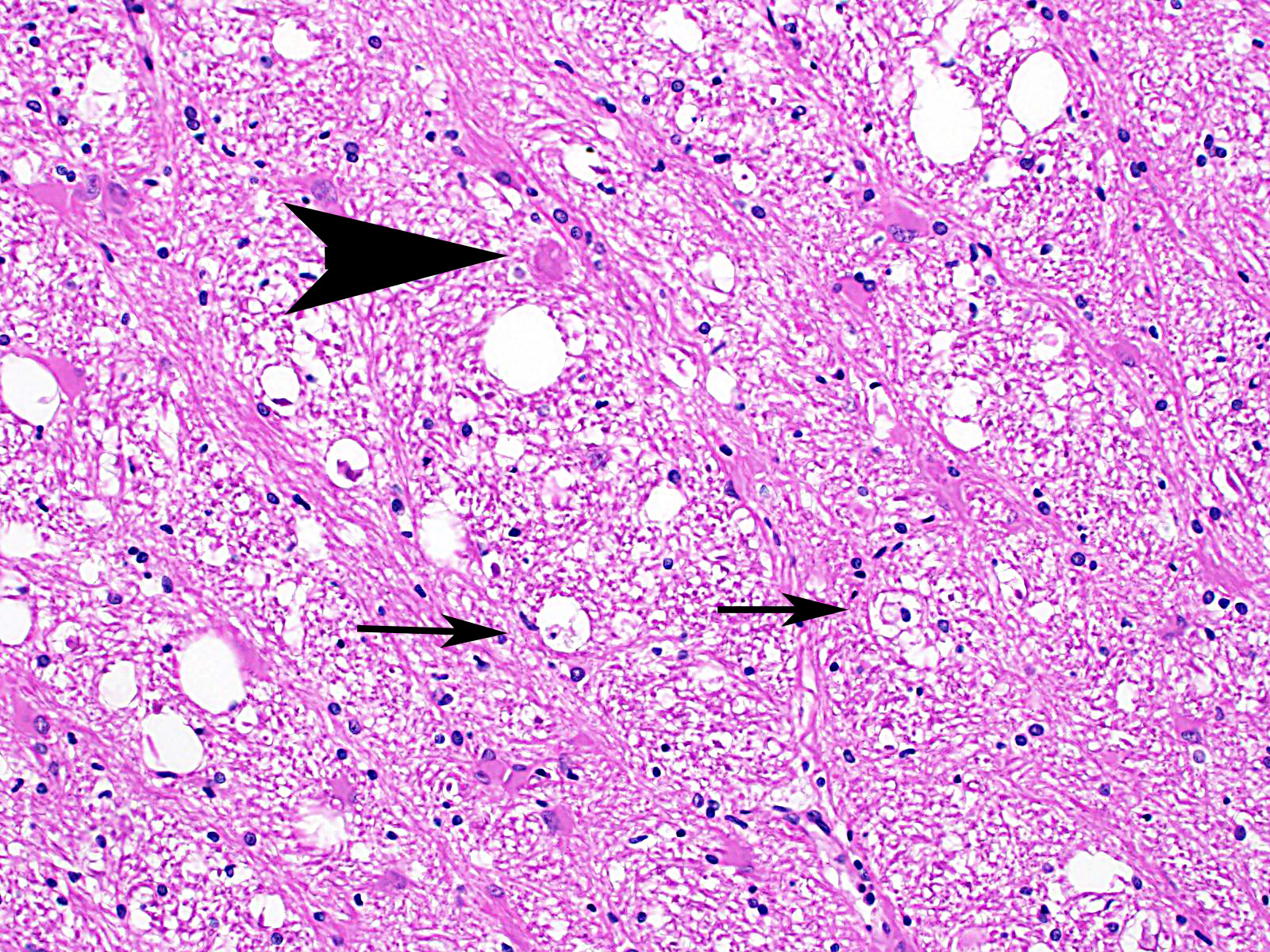

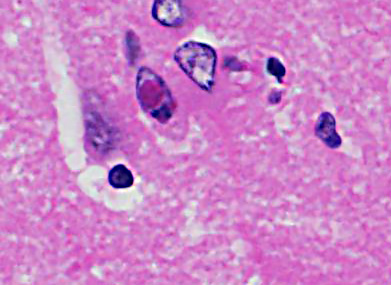

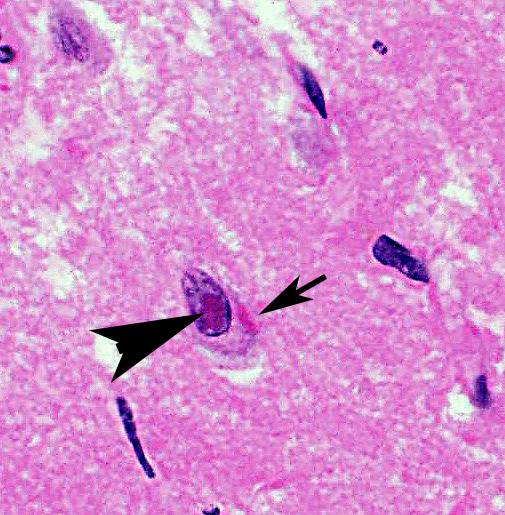

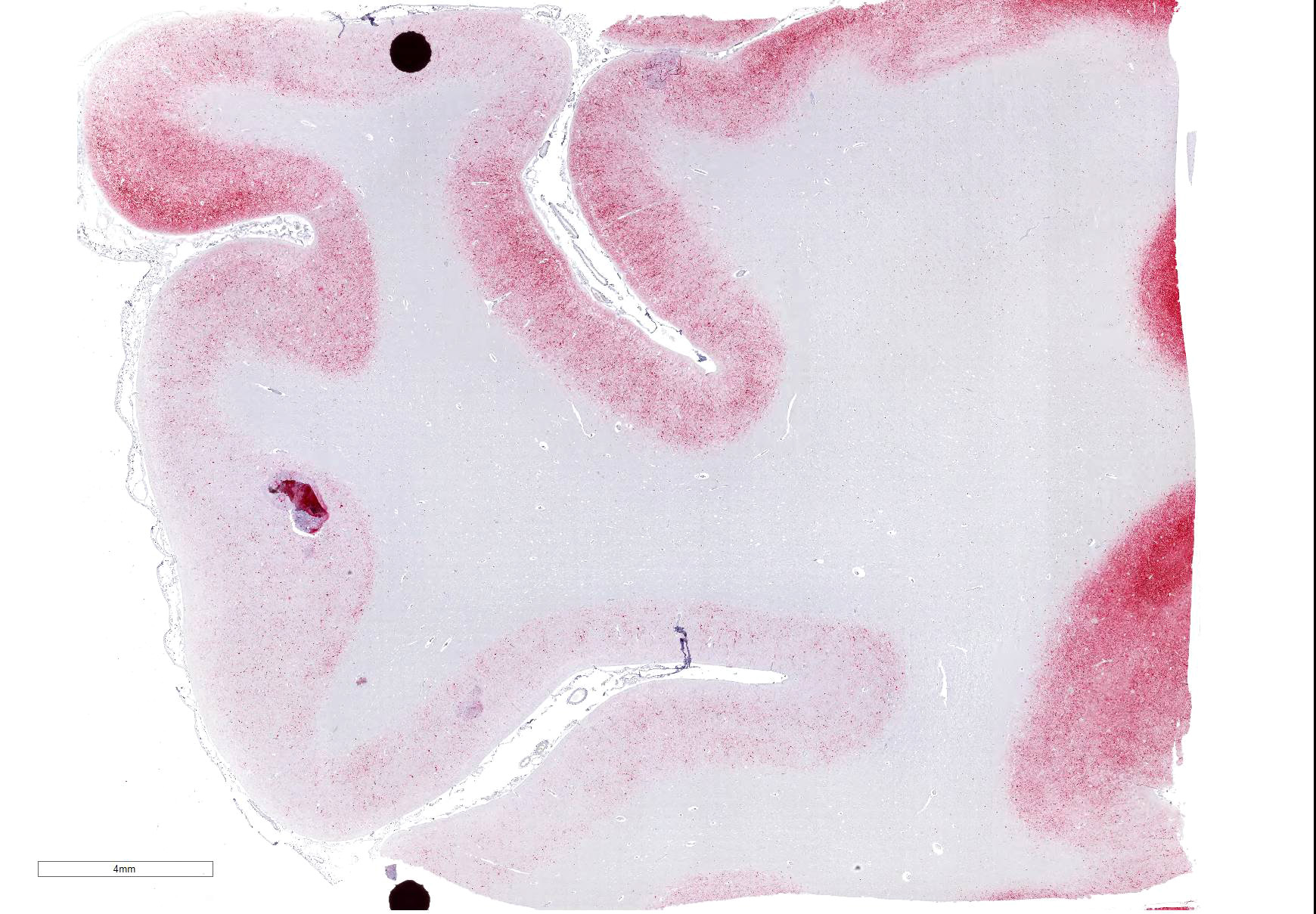

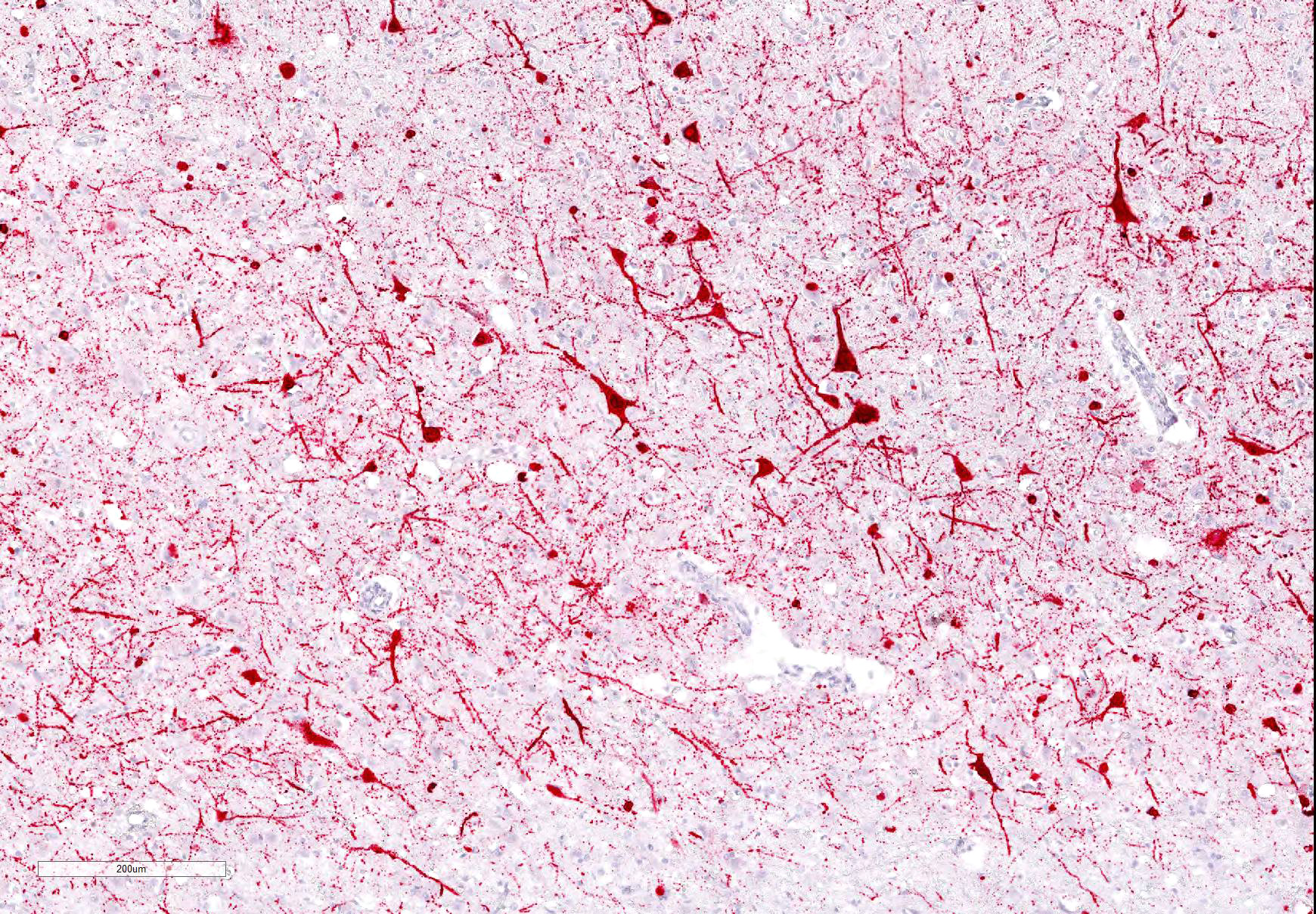

Cerebrum: Approximately 40% of myelin sheaths are lost with replacement by gitter cells (demyelination), or are markedly dilated (spongiosis) and occasionally contain swollen axons with bright eosinophilic axoplasm (spheroids) or gitter cells and cellular debris (Wallerian degeneration). Neurons and astrocytes often contain intranuclear viral inclusion bodies that marginate the chromatin and, rarely, 3-5 um eosinophilic intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies. Multifocally, there is vacuolation of the gray matter. Multifocally, there are small foci of glial nodules and numerous astrocytes with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric nuclei (gemistocytes). Occasionally, neuronal cell bodies are swollen and round with central chromatolysis (degeneration) or rarely, shrunken with bright eosinophilic cytoplasm with pyknotic nuclei (necrosis). Numerous neurons contain yellow to light green, granular material (lipofuscin). Multifocally, there is expansion of the Virchow Robin space around the blood vessels in the affected gray and white matter and leptomeninges by lymphocytes and plasma cells and lined by reactive endothelium.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnoses:

Cerebrum:

Demyelination, multifocal, marked with spongiosis, spheroids, lymphoplasmacytic

perivascular meningoencephalitis and eosinophilic intranuclear and

intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies, African lion (Panthera leo),

felid.

Contributor Comment: Canine distemper virus (CDV) is an important, ubiquitous infectious disease of domesticated dogs2, wild canids in the family Canidae2 (e.g., dingo, fox, coyote, jackal, wolf), wild cats in Felidae (e.g., African lion11, Bengal tiger3, Amur tiger18, leopard), Mustelidae13 (e.g., weasel, ferret, mink, skunk, badger, marten, otter), Procyonidae10 (e.g., raccoon, coati), Phocidae (e.g., Lake Baikal seal5), Rodentia (e.g., Asian marmot18) and nonhuman primate (e.g., rhesus macaque16) within the genus Morbillivirus in the family Paramyxoviridae. Other morbilliviruses include rinderpest, peste des petits ruminants virus, cetacean morbillivirus, phocine distemper virus and the measles virus.

CDV causes systemic disease often with respiratory, gastrointestinal and central nervous system (CNS) involvement. There are four distinct forms of CNS disease: 1) classic CDV encephalitis; 2) multifocal distemper encephalomyelitis in mature dogs; 3) "old dog" encephalitis (ODE)14; and 4) post-vaccinal canine distemper encephalitis. In large felids, fatal neurologic disease is due to a distinct CDV variant. Specifically, in African lions, it is thought they contract the virus from feral dogs or hyenas2. CNS disease is most common, followed by gastrointestinal and respiratory disease; lesions of the hard pads are rare10. Generalized seizure activity, the most common neurologic abnormality, usually culminates in acute death10.

CDV is a pantropic, negative-sense, single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus 150-300 nm in diameter. There is one recognized serotype with variable strain pathogenicity and tissue tropism. Virulence factors include hemagglutinin glycoproteins on the viral envelope, which mediate attachment to host cells and fusion glycoproteins which allow penetration of host cells and fusion of infected cells with uninfected cells22. Receptors include signaling lymphocyte activation molecule or SLAM (CD150)21, which is leukocyte-restricted and mediates entry into cells and CD46 which is widespread.

Infection is via inhalation and the virus infects macrophages in the upper respiratory tract or lungs and replicates in the tonsils and lymph nodes in the first 24 hours. There is cell-associated viremia by two days postinfection with spread to all lymphoid tissues and blood lymphocytes by two to five days postinfection, followed by lymphocytolysis, leukopenia and immunosuppression. Animals with adequate humeral/cellular immunity neutralize the virus by 14 days postinfection and may not shed virus. Animals with delayed intermediate humeral/cellular immunity, have a viral infection/persistence in the mucosal epithelium and brain and may develop neurologic disease and disease associated with epithelial infection. Animals that fail to develop neutralizing antibody by eight or nine days postinfection have virus that disseminates to the respiratory, gastrointestinal, urogenital and central nervous systems. The integumentary, exocrine and endocrine systems may also be affected. CDV is shed in all excretions during the systemic phase of infection which makes secondary infections with Adenovirus, Bordetella sp., Clostridium piliforme, Cryptosporidium sp., Escherichia coli, Encephalitozoon sp., Pneumocystis sp., Sarcocystis sp., and Toxoplasma sp. common.

CNS lesions develop one to three weeks after systemic signs or may occur after a subclinical infection. The virus is spread hematogenously to the brain and choroid plexus via macrophages shed into the cerebrospinal fluid and disseminates virus within the ventricles. The virus spreads to ependymal cells and spreads locally to infect astrocytes and microglia which leads to the characteristic white matter vacuolation (intramyelinic edema) thought to result from a direct effect of the virus on oligodendrocytes. ODE may be caused by infection with replication of a defective virus12. Post-vaccinal CDV occurs due to vaccination with a modified live vaccine and is often fatal in exotic carnivores (e.g., ferret, mink, lesser panda, grey fox). CDV rarely causes fatal encephalitis in young dogs, possibly due to immune stimulation by other canine viruses (e.g., canine parvovirus) at the time of vaccination. Vaccination of pregnant dogs can cause abortion or disease in puppies.

Disease with classic canine distemper is most common in 12-16 week old puppies. Early clinical signs include fever, conjunctivitis, coughing, vomiting, diarrhea, depression, anorexia and serous to mucopurulent oculonasal discharge. Clinical pathology reveals lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, regenerative anemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypergamma- and alpha-globulinemia. After one to four weeks, clinical signs include neurologic disease (e.g., seizures, cerebellar or vestibular ataxia, paraparesis, myoclonus) with minimal or no signs of epithelial infection. Hyperkeratosis of the footpads and nose and enamel hypoplasia are late manifestations. Of note, 50-70% of infections are subclinical.

Multifocal distemper encephalomyelitis in mature dogs occurs when CDV infects dogs at four to eight years of age and is a rare, chronic, progressive disease, but is not preceded by signs of classic distemper6. There is a slow, progressive course of weakness and incoordination, but no seizures. "Old dog" encephalitis (ODE) is extremely rare; most cases occur in dogs past middle age. There is an insidious onset of circling, incoordination, compulsive walking and pushing against fixed objects, but no paralysis or convulsions. The disease progresses over three to four months to coma and death. Post-vaccinal canine distemper encephalitis affects young dogs one to three weeks post-vaccination with a modified live CDV vaccine. There is an acute/subacute clinical course which lasts one to five days. Clinical signs are similar to the furious form of rabies, to include aggressiveness and attack behavior.

Grossly, CNS lesions are uncommon, but white matter softening with brown discoloration, with or without hemorrhage and reduction in brain size with dilated ventricles, can be seen in ODE. Non-CNS lesions include bronchointerstitial pneumonia7, catarrhal enteritis17, conjunctivitis15, hyperkeratosis of the foot pads and nose17, tonsillar enlargement4, thymic atrophy4, enamel hypoplasia9 and metaphyseal osterosclerosis9 in young growing dogs.

Histologically, eosinophilic intranuclear and/or intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies are most numerous 10-14 days postinfection. Intranuclear viral inclusion bodies are typically most obvious in the brain and intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies in the epithelium (especially the urinary bladder), but less obvious in the lymphoid tissues. In classic canine distemper, lesions usually involve both gray and white matter, but predominate in one. In the white matter there is demyelination, with early axon sparing, and status spongiosis with axonal degeneration and necrosis, which is most severe in the cerebellar peduncles, rostral medullary velum, optic tracts, hippocampal fornix, spinal cord and surrounding the fourth ventricle. There is also nonsuppurative encephalitis, gitter cells, astrocytosis and viral syncytia. In the gray matter, there are intranuclear viral inclusion bodies with or without intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies in the neurons, neuronal necrosis, mononuclear infiltrate surrounding necrotic neurons and nonsuppurative perivascular encephalitis with or without a mild meningitis.

In multifocal distemper encephalomyelitis in mature dogs, lesions are restricted to the CNS and are most prevalent in the cerebellum and white matter of the spinal cord. In contrast to ODE, the cerebral cortex is often spared. There is multifocal necrotizing nonsuppurative encephalitis with rare intranuclear viral inclusion bodies in astrocytes and demyelination in the internal capsule and corona radiate. In ODE, the cerebral cortex and brainstem are consistently affected. The characteristic features are widespread nonsuppurative perivascular encephalitis, intranuclear viral inclusion bodies in neurons and astrocytes and neuronal necrosis. Viral antigen is detectable by immunohistochemistry, however the virus cannot be isolated from the brain. In postÂvaccinal canine distemper encephalitis, the lesions are always restricted to the CNS and resemble classic canine distemper, but with relative sparing of white matter.

Ultrastructurally, tubular CDV nucleocapsids are seen in non-membrane bound intracytoplasmic aggregates8. Similar tubular structures may be seen in the nucleus despite lack of viral replication in the nucleus8.There is also destruction of ensheathing myelin envelope8. Diagnostic tests used to identify CDV include virus isolation, immunohistochemistry and the fluorescent antibody test. Differential diagnosis for CNS lesions include Toxoplasma gondii or Neospora caninum (random, multifocal, necrotizing foci in the grey and white matter with protozoa at the margins of the lesions), rabies virus (intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies in the hippocampal neurons and Purkinje cells with occasional lymphocytic perivascular cuffing), pseudorabies virus (polioencephalomyelitis with or without ganglionitis and intranuclear viral inclusion bodies in the neurons of the spinal ganglia, spinal cord, medulla and pons), granulomatous meningoencephalitis (progressive neurological disease of adult dogs with granulomatous inflammation), canine adenovirus type 1 (brainstem hemorrhages with mild vasculitis and intranuclear viral inclusion bodies in endothelial cells) and canine herpesvirus (usually puppies less than 21 days old with multifocal necrotizing lesions in many organs including lung, liver, kidneys and CNS).

Contributing Institution:

United States Army Institute of Surgical Research

Website: http://www.usaisr.amedd.army.mil/

JPC Diagnosis: Cerebrum: Meningoencephalitis, necrotizing and

lymphoplasmacytic, diffuse, moderate, with marked spongiosis and moderate

numbers of neuronal and astrocytic intra-nuclear and intracytoplasmic viral

inclusions.

JPC Comment: The contributor has done an excellent job in the description of the multisystemic pathogenesis of morbillivirus infection in the canine host, and much of this information is applicable to the disease in wild felids. Interestingly, transmission of virulent CDV to domestic cats has not been possible.1 A report of autopsy findings in large felids in an outbreak in several zoos in North America notes that the histologic findings between the disease in large felids and in dogs are quite similar with the exception of marked Type II pneumocyte hyperplasia in large felids and a more mild and patchy meningoencephalitis than that seen in canine cases.1

The disease is not new in large felids; retrospective studies of archived tissues have identified CDV antigens in cases prior to its initial description in this species.20 Most studies agree that outbreaks in large felids represent spillover from infected dogs1,14,20,21 and that this mode of transmission represents a very significant threat to a wide species of animals, many highly endangered, in both wild and captive settings. However, following widespread canine vaccination programs in proximity to the Serengeti ecosystem, the cyclic peaks in lion infections became desynchronized to those of the surrounding canine population, suggesting the possibility of other wildlife species may be maintaining and driving CDV infections in the lion population.20,21 Widespread vaccination programs (generally aimed at vaccinating 95% of local dog populations) have shown some efficacy in decreasing spillover into wildlife; problems associated with direct vaccination of susceptible wildlife species include mode of vaccine delivery and administration of boosters (often requiring tranquilization and handling of animals), safety and efficacy of distemper vaccines in target species, and the logistics and costs of administering this type of program.14

Clinical signs in wildlife species are similar to that of domestic dogs, but may vary as a result of host age, immune status, and viral strain variability. One of the major determinants of strain virulence is genetic variation in the H protein, one of six structural proteins of the CDV virus.14 The H protein binds to two cellular receptors in susceptible cells, the signaling lymphocyte adhesion molecular (SLAM, CD150), which is present on the surface of T and B lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. A second epithelial receptor, nectin-4, participates in cell entry as well as cell-to-cell spread.

The moderator reviewed various aspects of the pathogenesis and corresponding macroscopic and microscopic lesions of canine distemper virus in big cats as well as other susceptible carnivores. Peculiarities of CDV infection in large cats include prominent alveolar type 2 pneumocyte proliferation and a lack of inclusion bodies within the urinary bladder.1 She also stated than in addition to being a very illustrative case of a classic lesion, she chose this case to add this entity to the WSC database, where it is the first instance of CDV in a large felid.

References:

1. Appel MJ, Yates RA, Foley GL, et al. Canine distemper epizootic in lions, tigers, and leopards in North America. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994;6(3):277-288.

2. Beineke A, Baumgartner W, Wohlsein P. Cross-species transmission of canine distemper virus-an update. One Health. 13;(1):49-59.

3. Blythe LL, Schmitz JA, Roelke M, Skinner S. Chronic encephalomyelitis caused by canine distemper virus in a Bengal tiger. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983; 183(11):1159-1162.

4. Boes KM, Durham AC. Bone marrow, blood cells, and the lymphoid/lymphatic system. In: Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:759-760.

5. Butina TV, Denikina NN, Belikov SI. Canine distemper virus diversity in Lake Baikal seal (Phoca sibirica) population. Vet Microbial. 29;144(1-2):192-197.

6. Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:384-385.

7. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:574-576.

8. Cheville NF. Ultrastructural Pathology: The Comparative Cellular Basis of Disease. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:360-363.

9. Craig LE, Dittmer KE, Thompson KG. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:104-105.

10. Deem SL, Spelman LH, Yates, RA, Montali RJ. Canine distemper in terrestrial carnivores: a review. J Zoo Wild/ Med. 2000;31(4):441-451.

11. Harder TC, Kenter M, Appel MJ, Roelke-Parker, et al. Phylogenetic evidence of canine distemper virus in Serengeti's lions. Vaccine. 1995;13(6):521-523.

12. Headley SA, Amude AM, Alfieri AF, Bracarense AP, Alfieri AA, Summers BA. Molecular detection of canine distemper virus and the immunohistochemical characterization of the neurologic lesions in naturally occurring old dog encephalitis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009;21 (5):588-597.

13. Kiupel M, Perpifian. Viral diseases of ferrets. In: Fox JG, Marini RP, ed. Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014:439-450.

14. Loots AK, Mitchell E, Dalton DL, Kotze A, Venter EH. Advanceds in canine distemper fvirus pathogenesis research: a wildlife perspective. J Gen Virol 2017; 98:311-321.

15. Miller AD, Zachary JF. Nervous system. In: Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:890-891.

16. Origgi FC, Sattler U, Pilo P, Waldvogel AS. Fatal combined infection with canine distemper virus and orthopoxvirus in a group of Asian marmots (Marmota caudata). Vet Pathol. 2013;50(5):914-920.

17. Pesavento PA, Murphy BG. Common and emerging infectious diseases in the animal shelter. Vet Pathol. 2014;51 (2):478-491.

18. Qiu W, Zheng Y, Zhang S, et al. Canine distemper outbreak in rhesus monkeys, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(8):1541-1543.

19. Seimon TA, Miquelle DG, Chang TY, et al. Canine distemper virus: an emerging virus in wild endangered Amur tigers (Panthera tigris altaica). MBio. 2013;4(4):e00410- 13.

20. Terio KA, McAloose D, Mitchell E. Felidae. In: Terio KA eds., Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals, London, UK: Academic Press; 2018:pp 278-279.

21. Viana M, Cleaveland S, Matthiopoulos J, et al. Dynamics of a morbillivirus at the domestic-wildlife interface: Canine distemper virus in domestic dogs and lions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Feb 3;112(5):1464-9.

22. Wenzlow N, Plattet P, Witter R, Zurbriggen A, Grone A. lmmunohistochemical demonstration of the putative canine distemper virus receptor CD150 in dogs with and without distemper. Vet Pathol. 2007;44(6):943-948.

23. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:225-226.