Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 3, Case 4

Signalment:

5 year old, neutered male, Shetland sheepdog, dog (Canis familiaris).History:

This 5 year old Shetland sheepdog had a history of anorexia, diarrhea, vomiting and anuria of 4 days duration. Blood chemistry values were consistent with renal failure (exact values not reported). The dog was treated with intravenous fluids and diuretics, with no improvement in its condition. Due to the progression of the clinical signs and poor prognosis (without treatment), the owner elected for euthanasia. The dog was sent to our diagnostic laboratory and a complete necropsy was performed.Gross Pathology:

The dog was in good body condition. There were 10 and 20 ml of serous yellowish fluid in the pericardial sac and peritoneal cavity, respectively. Both kidneys showed a slightly irregular/pitted and mottled surface; on cut section, the cortex appeared slightly granular, and the medulla pale and firm. The stomach was empty, with a few shallow ulcers of varying size in the fundus.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

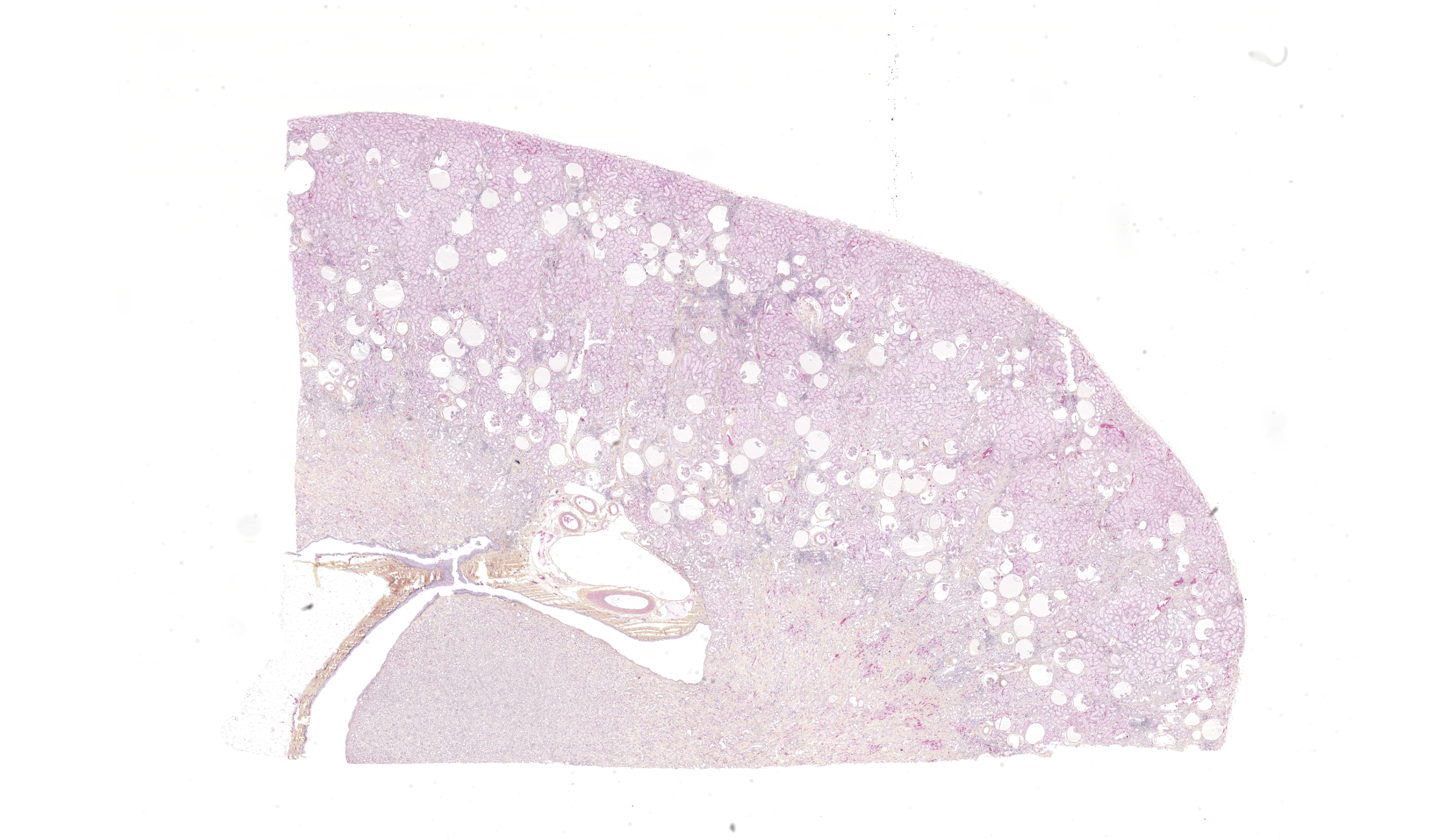

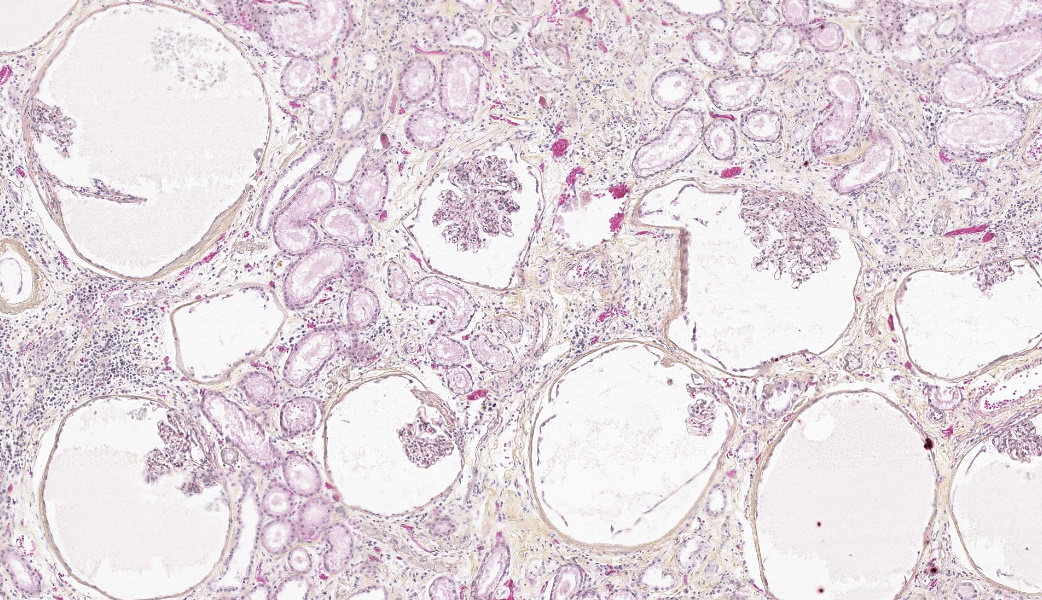

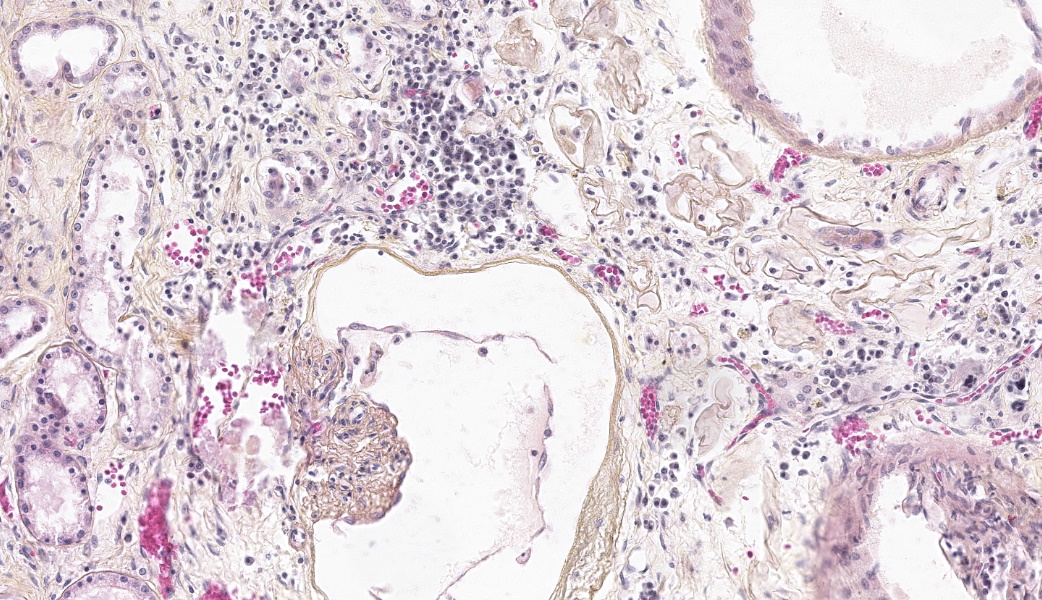

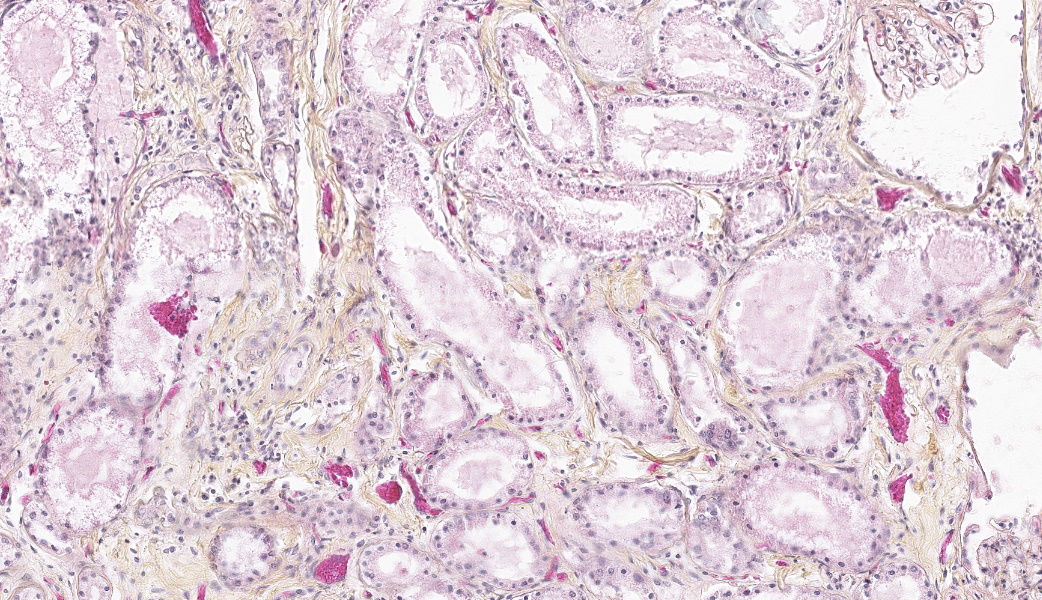

Both kidneys presented similar lesions. Almost all glomerular chambers (Bowman’s spaces) are variably dilated, often markedly (cystic dilation, up to about 500 µm), with a thickened/sclerotic, undulating and often mineralized Bowman’s capsule (basement membrane) Most glomerular tufts are either absent or shrunken and sclerotic with occasional synechiae. In the cortex, there is a moderate multifocal chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis with tubular atrophy and loss, peritubular sclerosis (thickened basement membrane) and occasional luminal crystals; tubular dilation is present but mild and multifocal. Several tubular basement membranes are diffusely mineralized. In the medulla there is a mild to moderate fibrosis with scant inflammation; rarely, dilated tubular structures lined by a simple columnar eosinophilic or stratified cubic/columnar amphophilic epithelium are present.Other significant changes in other organs (not submitted) included gastric mucosal mineralization and submucosal vasculopathy (“uremic gastritis”), and changes suggestive of bilateral parathyroid chief cell hyperplasia, consistent with renal secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Kidney: Glomerular chamber (Bowman’s space) dilation, diffuse, moderate to marked (cystic glomeruli), with moderate multifocal tubulointerstitial nephritis, consistent with glomerulocystic kidney disease

- Multifocal glomerular and tubular basement membrane (metastatic) mineralization

Contributor's Comment:

Glomerulocystic kidney disease (GCKD) is a rare disease reported mostly in humans, and also in 3 dogs and a single stillborn foal; it is part of the polycystic kidney disease (PKD) complex.1-7 In dogs, the disease has been described in a Shiba, a Belgian Malinois, and a Blue merle collie.3,6-7 In humans, GCKD is mostly observed in infants and young children, but adults may be affected.2,6 The canine cases involved adult animals, with ages ranging from 11 months to 5 years, as in our case. Diseases of the PKD complex are well described in humans and, to a lesser degree, in animals.1,4 They are part of the larger group of renal cystic diseases that include multiple hereditary, nonhereditary and acquired conditions.1,4 In diseases of the PKD complex, there is a progressive dilation of different portions of the nephron or collecting duct with the eventual formation of cysts.4,6 In GCKD, it is the glomerular chambers (Bowman’s spaces) that are cystic; in humans, the adjacent portion of the proximal convoluted tubules is also dilated.1 A glomerular cyst has been defined as a glomerulus with a 2- to 3-fold dilatation of its Bowman’s space.2Although periglomerular fibrosis and proximal tubular obstruction due to ischemic changes have been suggested as a possible mechanisms,4,7 the pathogenesis remains largely unknown in animals. In humans, the pathogenesis is still unclear, but there have been some advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology. For instance, it has been proposed that a ciliopathy may be involved, similarly to other renal cystic diseases; several genes involved in renal development are also under investigation (GCKD can develop due to changes in Wnt or hedgehog signaling).2 In humans, GCKD is often associated with other lesions or diseases, including autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and the tuberous sclerosis complex.1,2 Three clinical variants have been originally described: malformation syndrome-associated GCKD, renal dysplasia-associated GCKD, and primary GCKD (heritable and sporadic).2,6 A more recent classification of GCKD has been published in 2007: 1) familial nonsyndromic (e.g. ADPKD in infants), 2) associated with inheritable malformation syndromes (e.g. tuberous sclerosis complex), 3) syndromic, non-Mendelian (e.g. trisomy 9, 13 or 18), 4) sporadic (new mutations), and 5) acquired and dysplastic kidneys (e.g. hemolytic uremic syndrome and obstructive uropathy).2 There are mouse models of GCKD that are relevant to the human disease.2

As with other chronic glomerular diseases, secondary chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis will develop in time.3 Glomerulocystic disease

(GCKD) must be differentiated from “glomerulocystic change”, in which cystic glomeruli are secondary to renal scarring from different renal pathologies.3 In the present case, the chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis is considered to be secondary to the glomerular pathology.

Contributing Institution:

Faculty of veterinary medicine, Université de Montréal, St-Hyacinthe, Quebec, Canada: http://www.medvet.umontreal.caJPC Diagnoses:

Kidney: Glomerulocystic atrophy, chronic, diffuse, severe, with tubular degeneration and necrosis, basement membrane mineralization, and multifocal lymphocytic interstitial nephritis and fibrosis.JPC Comment:

The last case for today’s conference represented a condition so uncommonly encountered that there was prolonged discussion about differential diagnoses and why this condition was not those things. Differentials included Lyme disease, which would have tubular degeneration, lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis, and glomerulonephritis; Renal dysplasia, which has a trifecta of findings including fetal glomeruli, primitive tubules, and fetal mesenchyme; and urolithiasis leading to hydronephrosis, which would have dilation/ectasia of tubules at all levels, renal pelvic dilation, and would likely have protein casts within tubules. The defining features of glomerulocystic disease that separate it from these other conditions are dilation of the glomerular tuft with cystic expansion of Bowman’s space and glomerular atrophy with no concurrent glomerulonephritis. Additionally, the proximal convoluted tubules (PCTs) closest to the glomeruli are the most affected and may also demonstrate a degree of dilation due to stenosis between the glomeruli and the PCTs. There may also be a lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis, which was seen in this case.An interesting feature of this condition is that the basement membranes of multiple tubules and glomeruli were mineralizing, even in the absence of obvious degeneration. Hmm! A review of clinical pathology data from a pair of 2008 case reports in dogs with glomerulocystic disease was conducted during conference and revealed that dogs affected with this condition can have an abnormal Calcium/Phosphorus ratio secondary to their renal disease, so much so that metastatic mineralization can occur.5

Additionally, the dogs in the case report had low hematocrit, low hemoglobin, and low reticulocyte count.5 All three of these can be explained by the loss of the renal juxtaglomerular apparatus in this disease that is responsible for sensing feedback on erythrocyte concentrations within the blood and subsequently stimulating erythropoietin production when needed. If there’s no stimulus to make more red blood cells, of course your HCT, Hbg, and reticulocytes are going to be lacking and an anemia will result.

Lastly worth nothing is that the dogs in the case report were also azotemic and acidotic.5 The metabolic acidosis in these cases is due to a combination of the azotemia and anemia. Fewer red blood cells to transport oxygen leads to tissue hypoxia and an increase in anaerobic glycolysis, which produces lactic acid. Azotemia causes acidosis due to the kidneys being unable to properly excrete waste products that generate acid, such as phosphates and sulfates, and they lose the ability to regenerate and resorb bicarbonate, which is a vital buffer of acids in the bloodstream. Understanding how these clinical findings translate to the lesions pathologists see is critical to being able to logically follow a disease pathogenesis, to know where to look for lesions in particular diseases, and to understand how to make sense of pathophysiology. As such, the clin path review during this conference case was well-received by all participants and much appreciated.

References:

- Bisceglia M, Galliani CA, Senger C, Stallone C, Sessa A. Renal cystic diseases: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:26-56.

- Bissler JJ, Siroky BJ, Yin H. Glomerulocystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:2049-56.

- Chalifoux A, Phaneuf J-B, Olivieri M, et al. Glomerular polycystic kidney disease in a dog (blue merle collie). Can Vet J. 1982;23:365-368.

- Maxie, MG, Newman SJ. Urinary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of domestic animals, vol.2. Fifth Edition. Elsevier Saunders. Philadelphia, PA, 2007:281-458.

- Morales E, Montesinos-Ramirez LI, Garcia-Ortuno LE, and Nunez-Diaz AC. Glomerulocystic kidney disease in two dogs with renal failure. Veterinaria Mexico. 2008:39(1):97-110.

- Ramos-Vara JA, Miller MA, Ojeda JL, et al. Glomerulocystic kidney disease in a Belgian malinois dog, an ultrastructural, immunohistochemical, and lectin-binding study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2004;28:33-42.

- Takahashi M, Morita T, Sawada M, et al. Glomerulocystic kidney in a domestic dog. J Comp Path. 2005;133:205-208.