Signalment:

6-year-old castrated male Yorkshire terrier dog (Canis familiaris)

Per history provided, Milo is a 6-year-old castrated male Yorkshire terrier dog that was diagnosed with tra-cheobronchitis for the past month and was placed on antibiotic therapy. The dog developed sudden onset of hindlimb weakness and was unable to walk on both hind limbs. He collapsed acutely, failed to revive when administered cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and was submitted for necropsy.

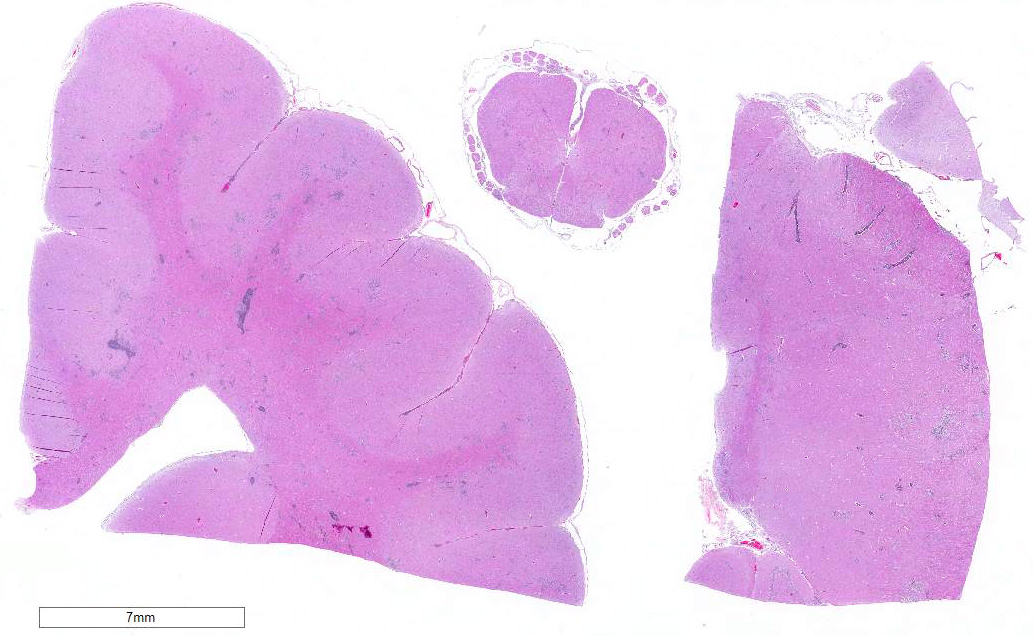

Gross Description:

There were no significant gross findings noted.

Histopathologic Description:

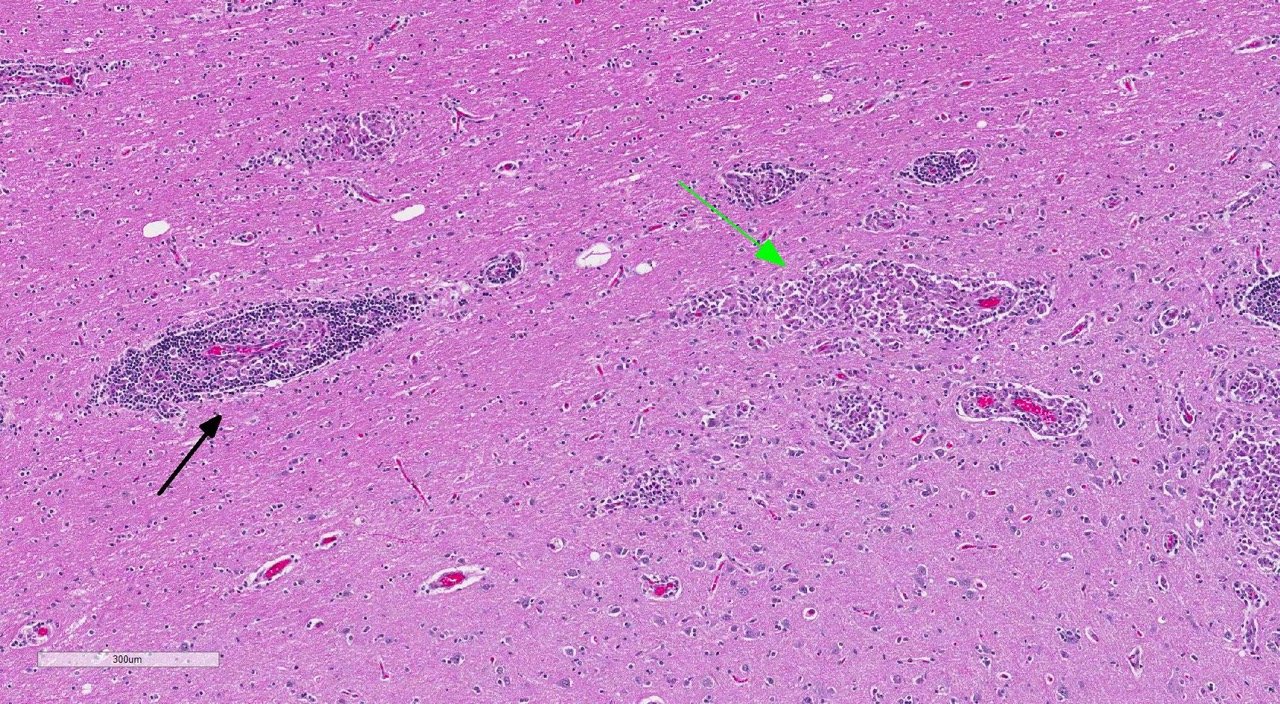

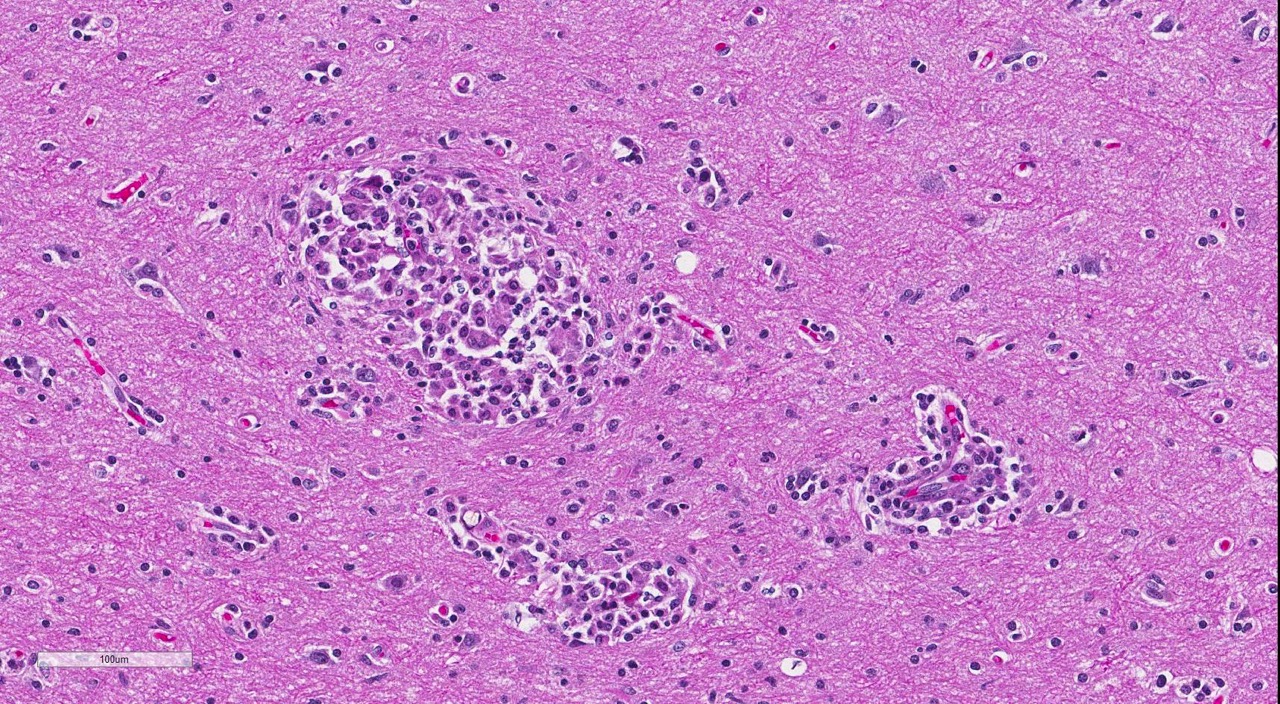

Brain: Multi-focally, expanding the meninges and Virchow-Robins space primarily within the white matter and less severely affecting the grey matter of the cerebrum, cerebellum and brainstem, are numerous intense inflammatory foci that often coalesce. Inflammatory cells are comprised of large numbers of macrophages, lymphocytes, with fewer plasma cells and neutrophils. The macrophages often appear epithelioid cells and form granulomatous foci that efface and replace neuropil. Within neuropil adjacent to granulomatous foci are large numbers of glial cells (gliosis) and reactive gemistocytic astrocytes. Both lymphocytes and ma-crophages are arranged in dense and often whirling, perivascular cuffs. Mitoses in the macrophage population are present at 1-3 per high power field (400x) in areas of perivascular cuffs. Endothelium associated with the perivascular cuffing is reactive, and lined by plump and hypertrophied endothelial cells, and vessel walls are infiltrated by the mononuclear cells described above.

Spinal cord: Diffusely expanding meninges and multifocally replacing white and grey matter of the spinal cord are similar inflammatory cells as those described above for the brain sections. Perivascular gran-ulomatous, lymphocytic cuffs are present in neuropil and meninges.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Brain: 1. Severe, multifocal to coalescing lymphohistiocytic encephalitis

2. Severe, diffuse lymphohistiocytic meningitis

Spinal cord: 1. Severe, multifocal lymp-hohistiocytic myelitis

2. Severe, diffuse lymphohistiocytic meningitis

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

GME can be classified as focal, dis-seminated (multifocal) and ocular.3 The focal type is characterized by coalescing granulomas that form a space-occupying lesion and associated clinical signs, and are more common in the cerebrum and brainstem.3 The disseminated form affects more than one of the following sites: cer-ebrum, brainstem, spinal cord, cerebellum, meninges and optic nerves.3 The ocular form is associated with optic neuritis and oc-casionally uveitis, retinal hemorrhage or retinal detachment.3 The exact etiology of GME is unknown, although infectious causes and immune-mediated disease have been proposed. Antemortem diagnosis of GME is typically based on CSF analysis, characterized by increased leukocyte count, mononuclear pleocytosis and increased protein content.3 However, changes can be variable and may be steroid dependent.3 Definitive diagnosis of the disease is based on brain biopsy.3 Treatment for GME is largely based on immunosuppression with corticosteroid therapy, and azathioprine, cy-tosine arabinoside, procarbazine, cy-closporine and radiation therapy have more recently been attempted in treatment regime.3 In general, prognosis of dogs with GME is poor. Considering the clinical history of tracheobronchitis in this dog and the nature of inflammatory cells, the differential diagnosis includes canine distemper (Morbillivirus) infection. There were no intranuclear or intracytoplasmic viral inclusions present in any of the sections examined to further support a viral etiology in this case. Ancillary testing using immunohistochemistry to label viral antigen in the brain sections would be useful to definitively rule out canine distemper in this case. Fungal or protozoa infection are lower on the differential list as organisms were not observed in any of the examined sections.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Aside from (or in conjunction with) an autoimmune disorder, infectious agents have long been suspected to be involved in the pathogenesis of GME (and NME), and the phenomenon of molecular mimicry has also been implicated.Infectious agents have not been identified via light microscopy or culture and molecular techniques have failed to identify a viral agent; however, molecular techniques have identified Mycoplasma canis (an agent not typically associated with CNS disease) in cases of both GME and NME.To date, the precise role of M. canis in the pathogenesis of GME and NME remains unclear.1 Aside from explanations involving an infectious agent and immune dysregulation, it has also been postulated that GME may represent a lymph-oproliferative disorder.7 Overall, the common view is that this condition is mul-tifactorial with a complex pathogenesis involving genetic factors, immune dy-sregulation and environmental factors (i.e. pathogens).1,7

The conference histologic description mirrored the contributors description above. Additional features described include mild rarefaction and vacuolation of the neuropil adjacent to inflammatory aggregates, and microgliosis (in addition to the astrocytosis noted above). Although many of the astrocytes appear hypertrophied/reactive, the majority have not yet reached the characteristic gemistocytic stage.Low numbers of necrotic neurons are also present, although this is not a prominent feature.Perivascular cuffs consist primarily of lymphocytes, while most of the histiocytes are localized to the neuropil adjacent to perivascular cuffs.The moderator noted that the distinct asymmetric nature of the lesions, particularly within the perivascular cuffs, is a characteristic feature of GME. She also pointed out the vas-culocentric nature of the meningeal inflammation and how it is not evenly distributed, which is another common feature of this entity. Conference participants briefly discussed differential diagnosis for GME, including viral encephalitis, pointing out that viruses generally result in primarily lymphocytic inflammation.The histiocytic component in GME is an important diagnostic clue, as well as the fact it affects both grey and white matter.The moderate commented that, in general, GME is easier to diagnose in more chronic, severe cases and that it is important to trim in the eyes in suspected cases of GME, as inflammation is often seen surrounding the optic nerve.

References:

1. Barber RM, Porter BF, Li Q, May M, et al.Broadly reactive polymerase chain reaction for pathogen detection in canine granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis and necrotizing meningoencephalitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2012; 26:962-968.

2. Cordy DR. Canine granulomatous eningoencephalomyelitis. Vet Pathol. 1979; 16(3):325-33.

3. Emma JO, Merrett D, and Jones B. Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis in dogs: A review. Ir Vet J. 2005 Feb 1; 58(2):86-92.

4. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007: 442-443.

5. Park ES, Uchida K, Nakayama H.Comprehensive immunohistochemical studies on canine necrotizing men-ingoencephalitis (NME), necrotizing leukoencephalitis (NLE) and granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME). Vet Pathol. 2012; 49(4):682-692.

6. Park ES, Uchida K, Nakayama H.Th1-, Th2-, and Th17-related cytokine and chemokine receptor mRNA and protein expression in brain tissues, T cells, and macrophages of dogs with necrotizing and granulomatous meningoencephalitis. Vet Pathol. 2013; 50(6):1127-1134.

7. Schatzberg SJ.Idiopathic gran-ulomatous and necrotizing inflam-matory disorders of the canine central nervous system.Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010; 40(1):101-20.