Signalment:

Gross Description:

Liver: There are multifocal to coalescing circular regions of necrosis with depressed pale tan/yellow centers surrounded by a slightly raised, often hemorrhagic rim. Lesions range in size from 0.5 to 3.0 cm in diameter and are disseminated randomly throughout the parenchyma.

Ceca: Both ceca are moderately distended and fluid filled with thickened hyperemic walls mottled tan to dark red. The mucosal surface is multifocally ulcerated with occasional partially adhered caseous debris amidst abundant luminal hemorrhagic exudate.

Histopathologic Description:

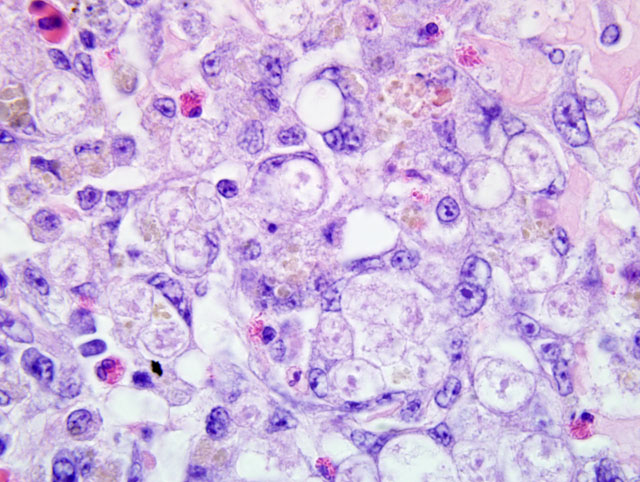

Cecum: Diffusely expanding the lamina propria and multifocally extending transmurally with effacement of up to 50% of the muscular coat is an inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of lymphocytes and macrophages with fewer plasma cells and heterophils admixed with numerous 12-20μm diameter protozoal trophozoites similar to those described within the liver. There is extensive loss of crypts and remnant crypts are hyperplastic, tortuous and ectatic with piling of 2-3 epithelial cells layers, and luminal aggregates of detached epithelial cells and degenerate leukocytes, mainly heterophils (crypt microabscesses). There is multifocal extensive mucosal ulceration, and in some sections the cecal lumen contains a dense core of eosinophilic cellular and karyorrhectic debris, erythrocytes, fibrin, degenerate protozoal trophozoites, macrophages and heterophils, and aggregates of rod shaped bacteria (cecal core).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Multifocal and coalescing, random, necrotizing, sub-acute-tochronic, lymphohistiocytic and heterophilic hepatitis with biliary hyperplasia and intralesional protozoal trophozoites, etiology consistent with Histomonas meleagridis.

Cecum: Transmural, marked, sub-acute-to-chronic lymphohistiocytic and heterophilic typhlitis with fibrinonecrotic core (variable) and intralesional protozoal trophozoites consistent with H. meleagridis.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The role of the cecal worm Heterakis gallinarum as in intermediate host has been well-described.(2,3) The exact mechanism of infection of Heterakis eggs with histomonads remains unknown, but it has been suggested that the protozoan may be transferred to the female worm during mating and are then incorporated into embryonated eggs.(2) Infected eggs pass in feces where they may be ingested directly by birds or by earthworms who may serve as a transport host. Ingestion of either egg-laden feces or earthworms by the bird results in transport to the cecum where flagellated trophozoites are released from the nematode egg, multiply in the cecal lumen and penetrate the cecal wall. The tissue stage loses the flagella becoming amoeboid. Eventually the histomonads gain entry into the bloodstream and are carried to the liver via the hepatic-portal system. It is important to note that the fragile trophozoite of Histomonas, which cannot survive long outside of any of its hosts, would be unable to survive passage through the stomach if not within a nematode egg or an earthworm. Therefore, fecal oral transmission is not thought to be an important route of transmission. Interestingly, some recent publications have shown the existence of a cyst stage in some species of Histomonas in vitro sparking interest in the possibility of this happening under certain conditions in the natural disease allowing for persistence in the environment and the possibility of oral transmission.(4,7)

Extension to the liver as described above occurs at a higher rate in turkeys than chickens, with a much higher associated mortality rate. Concurrent infection with Eimeria tenella results in increased liver lesions in chickens. Histomonad virulence also requires the presence of cecal bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Clostridium perfringens, and/or Bacillus subtilis, especially in turkeys.(2,3) As mentioned previously, turkeys suffer from a much higher mortality rate than chickens, with the latter being better able to control the disease but still suffering decreased productivity. A recent publication showed that chickens mount a more effective innate immune response to H. meleagridis in the ceca than do turkeys resulting in better control of parasite numbers in chickens.(5) Furthermore, unregulated cell-mediated immunity in the liver is more pronounced in the turkey than the chicken often leading to lymphoid depletion of the spleen.(5) Another difference of histomoniasis in turkeys is that, in addition to transmission via ingestion of Heterakis eggs, turkeys appear to be able to transmit histomonads directly via cloacal drinking where cloacal droppings from an infected bird can be pulled retrograde into the ceca of a susceptible bird if the droppings contact the vent of the uninfected bird.(2,3)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatitis, random, necrotizing, lymphohistiocytic and heterophilic, multifocal coalescing, severe, with biliary hyperplasia and protozoal trophozoites, etiology consistent with Histomonas meleagridis.

2. Cecum: Typhlitis, transmural, lymphohistiocytic and heterophilic, diffuse, severe, with fibrinonecrotic core and protozoal trophozoites, etiology consistent with Histomonas meleagridis.

Conference Comment:

Conference participants noted that blackhead is an imprecise colloquialism in that cyanosis of the head is neither a constant feature nor a unique clinical sign of histomoniasis.(6) Other diseases, such as turkey enteric coronavirus (bluecomb disease), avian influenza, and various respiratory pathogens may cause a cyanotic head in turkeys and chickens. Gross digital images were shown during the conference to reinforce the point that the macroscopic lesions of histomoniasis are very distinctive, and when classical lesions are present in both the liver and cecum simultaneously, the findings are considered pathognomonic for the condition. When only cecal cores are present, other etiologic considerations would include salmonellosis for both chickens and turkeys, and Eimeria tenella in chickens.

In addition to histomoniasis, cecal heterakiasis was also discussed by participants. Although H. gallinarum can cause thickened cecal walls, nodule formation, and inflammation in its own right in turkeys and chickens, its practical and economic importance is the nematodes ability to serve as a carrier for H. meleagridis.(1) In pheasants, however, Heterakis isolonche causes severe cecal disease with mortality rates that may exceed 50%.(2) The disease in pheasants is characterized by a marked inflammatory response, fibrosis, and coalescing cecal wall nodules.

References:

2. McDougald LR. Histomoniasis (Blackhead) and other protozoan diseases of the intestinal tract. In: Saif YM, ed. Disease of Poultry, 12th ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing Professional; 2008:1095-1100.

3. McDougald LR. Blackhead disease (Histomoniasis) in poultry: a critical review. Avian Dis. 2005;49:462-476.

4. Munsch MH, Mehlhorn S, Al-Quraishy AR, Lotfi, Hafez HM. Molecular biological features of strains of Histomonas meleagridis. Parasitol Res. 2009;104:1137-1140.

5. Powell FL, Rothwell L, Clarckson MJ, Kaiser P. The turkey, compared to the chicken, fails to mount an effective early immune response to Histomonas meleagridis in the gut. Parasite Immunol. 2009;31:312-327.

6. Trees AJ. Parasitic diseases. In: McMullin PF, ed. Poultry Diseases, 6th ed., Edinburgh: Elsevier Limited; 2008:458-459.

7. Zaragatzki E, Hess M, Grabensteiner E, Abdel-Ghaffar F, Al-Rasheid K, Mehlhorn H. Light and transmission electron microscopic studies of the encystation of Histomonas meleagridis. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:977-983.