Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 16

29 January 2020

Dr. Ingeborg

Langohr, DVM, PhD, DACVP

Professor

Department of Pathobiological Sciences

Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine

Baton Rouge, LA

CASE I: S1809996 (JPC 4135077).

Signalment: A 3-month-old, male, mixed-breed pig (Sus scrofa)

History: This pig had no previous signs of illness, and was found dead.

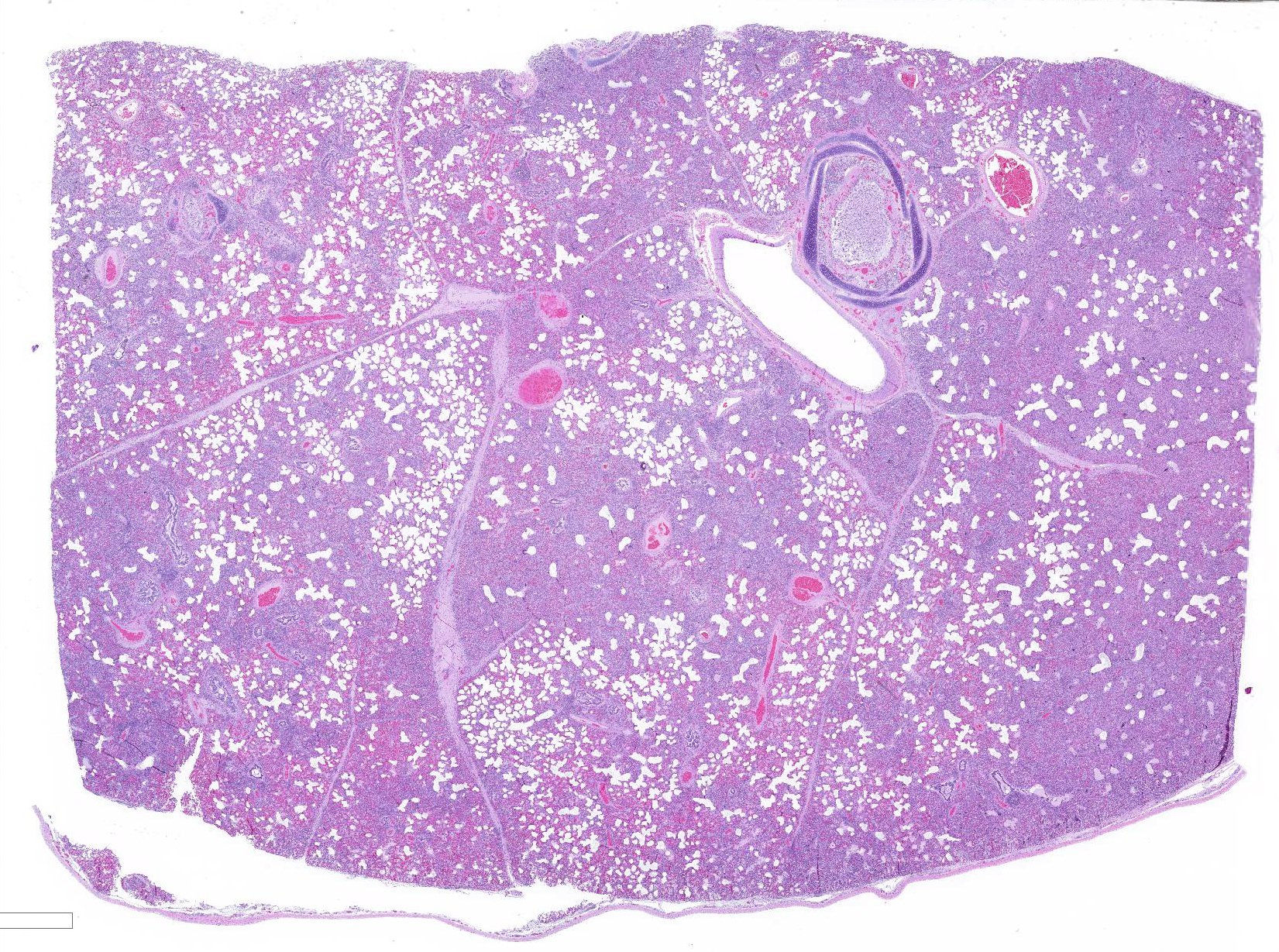

Gross Pathology: Approximately 70% of the lungs, primarily in the cranial regions of the lobes, were patchy dark red, and firm compared to the more normal areas of lung.

Laboratory results: Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) PCR was positive from splenic tissue, and PRRS IHC was strongly immunoreactive within the cytoplasm of macrophages in the affected lung tissue. Porcine influenza virus PCR, porcine circovirus ? 2 IHC, and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae IHC were all negative. Small numbers of E. coli were isolated from the cranioventral lung with aerobic culture.

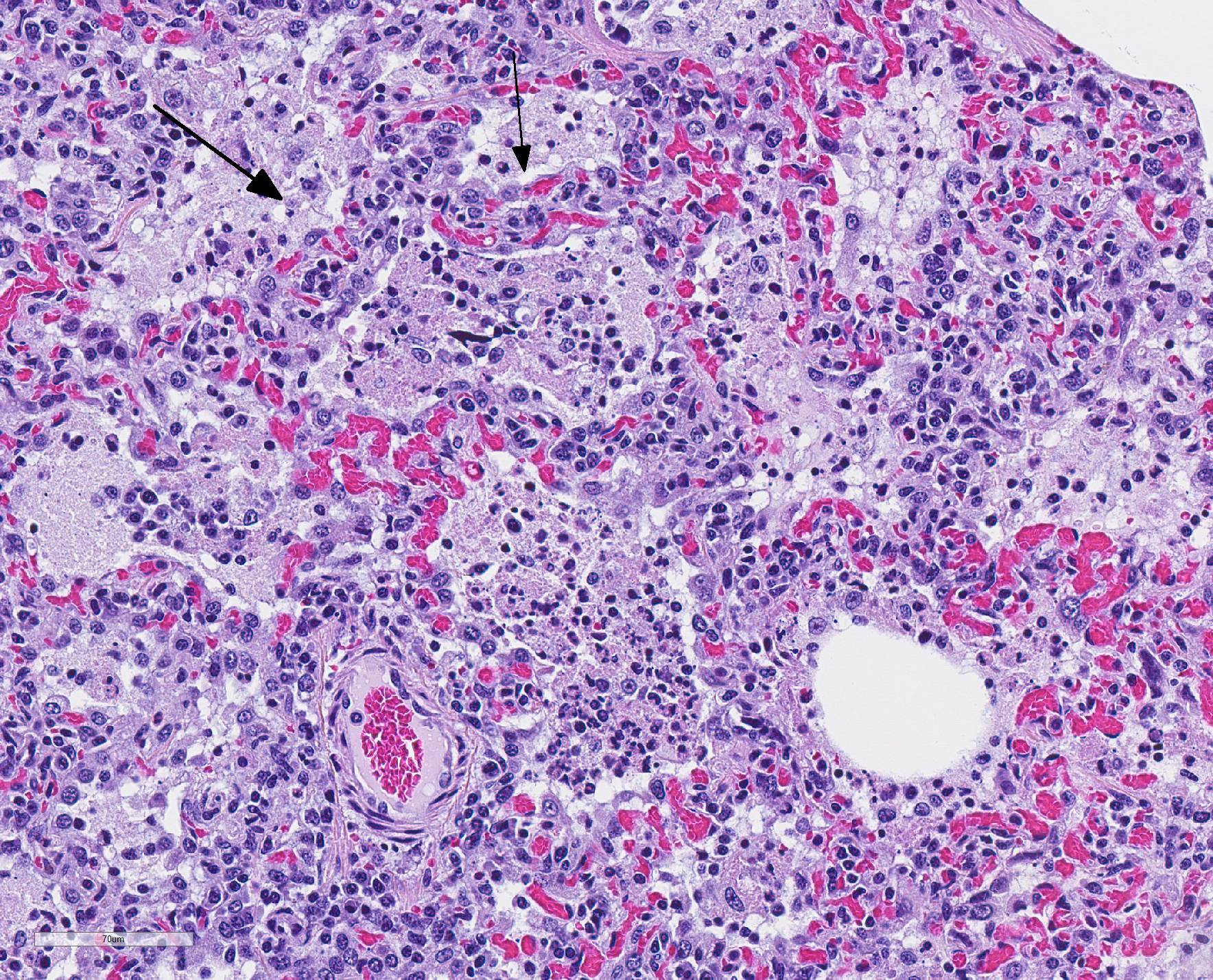

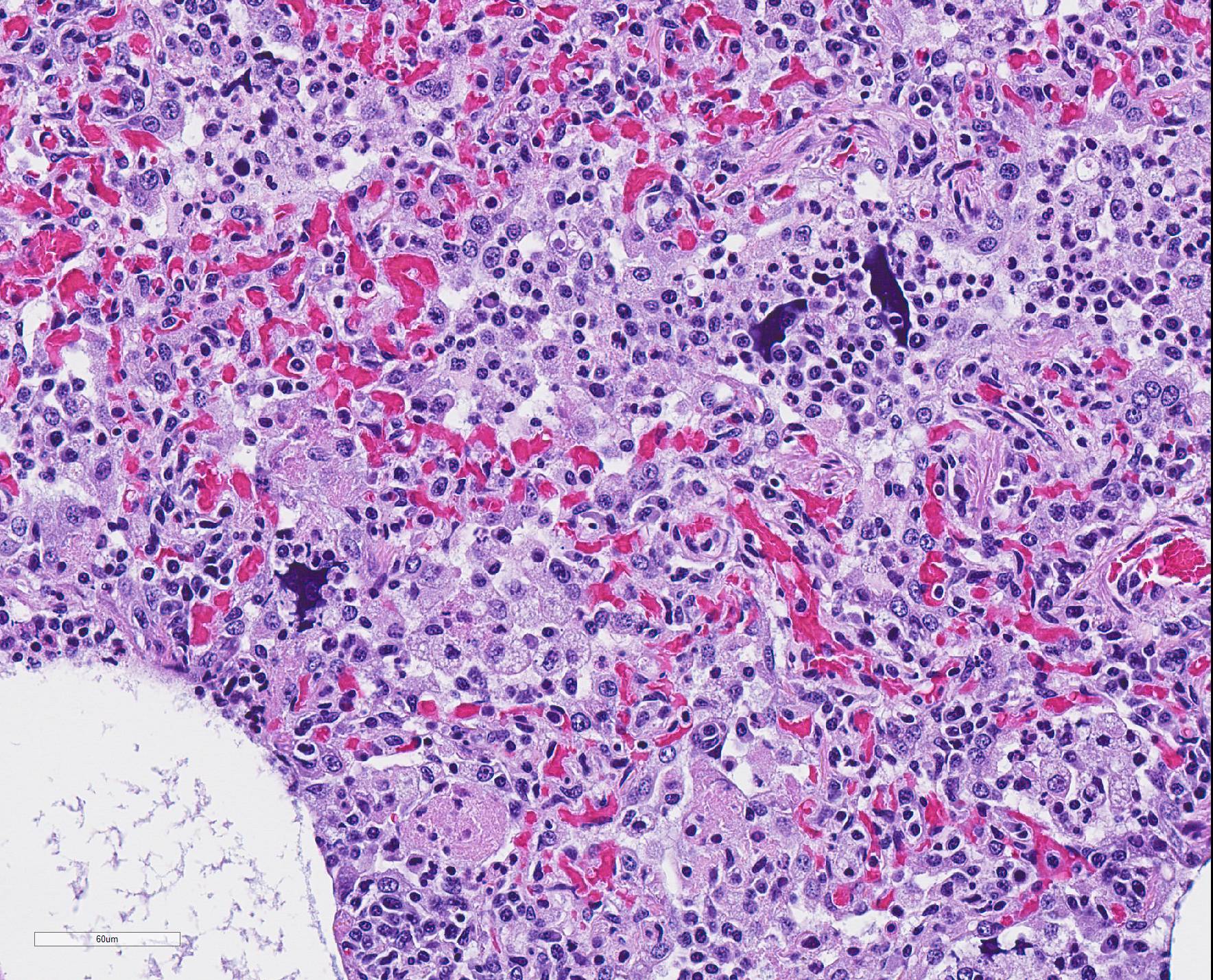

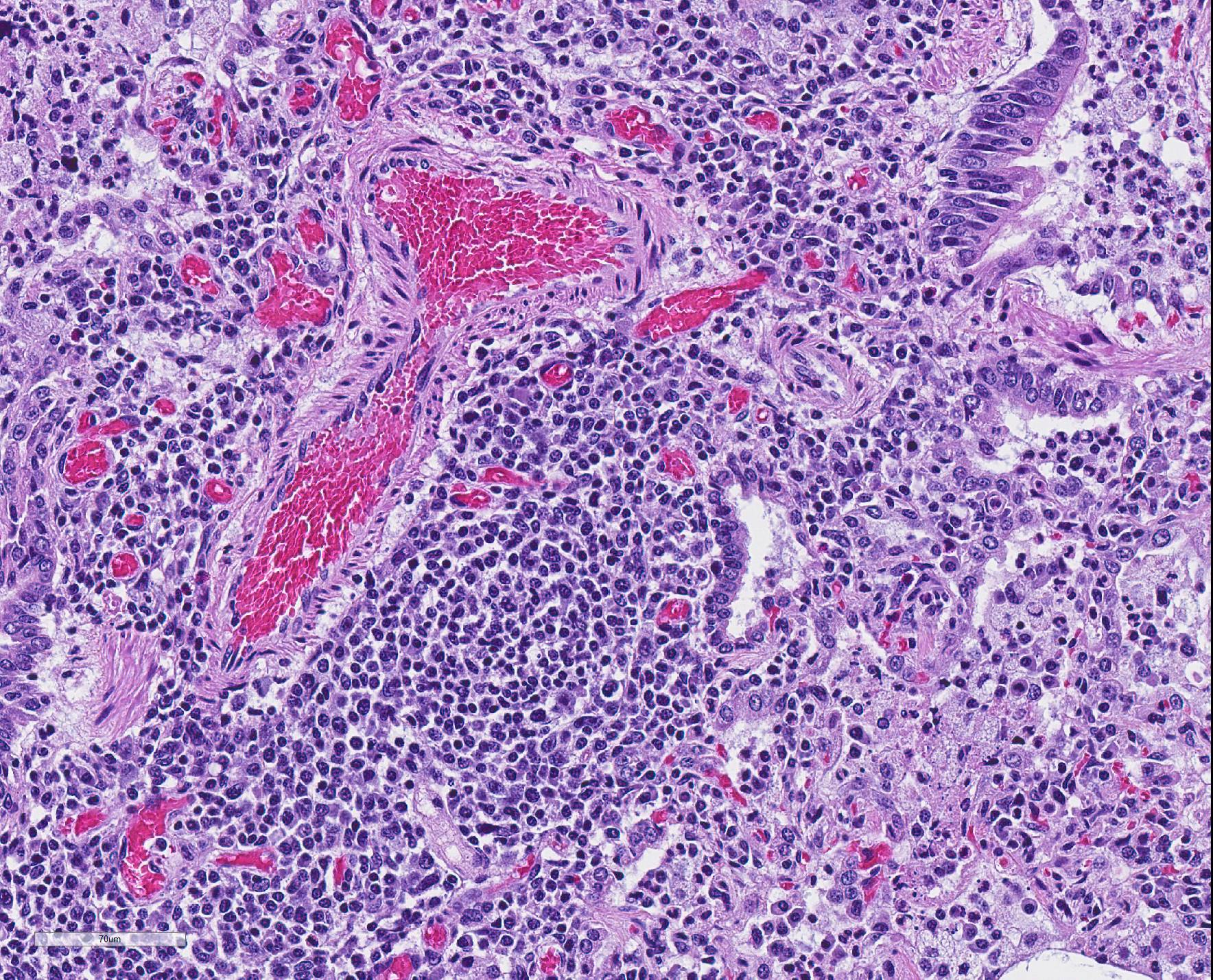

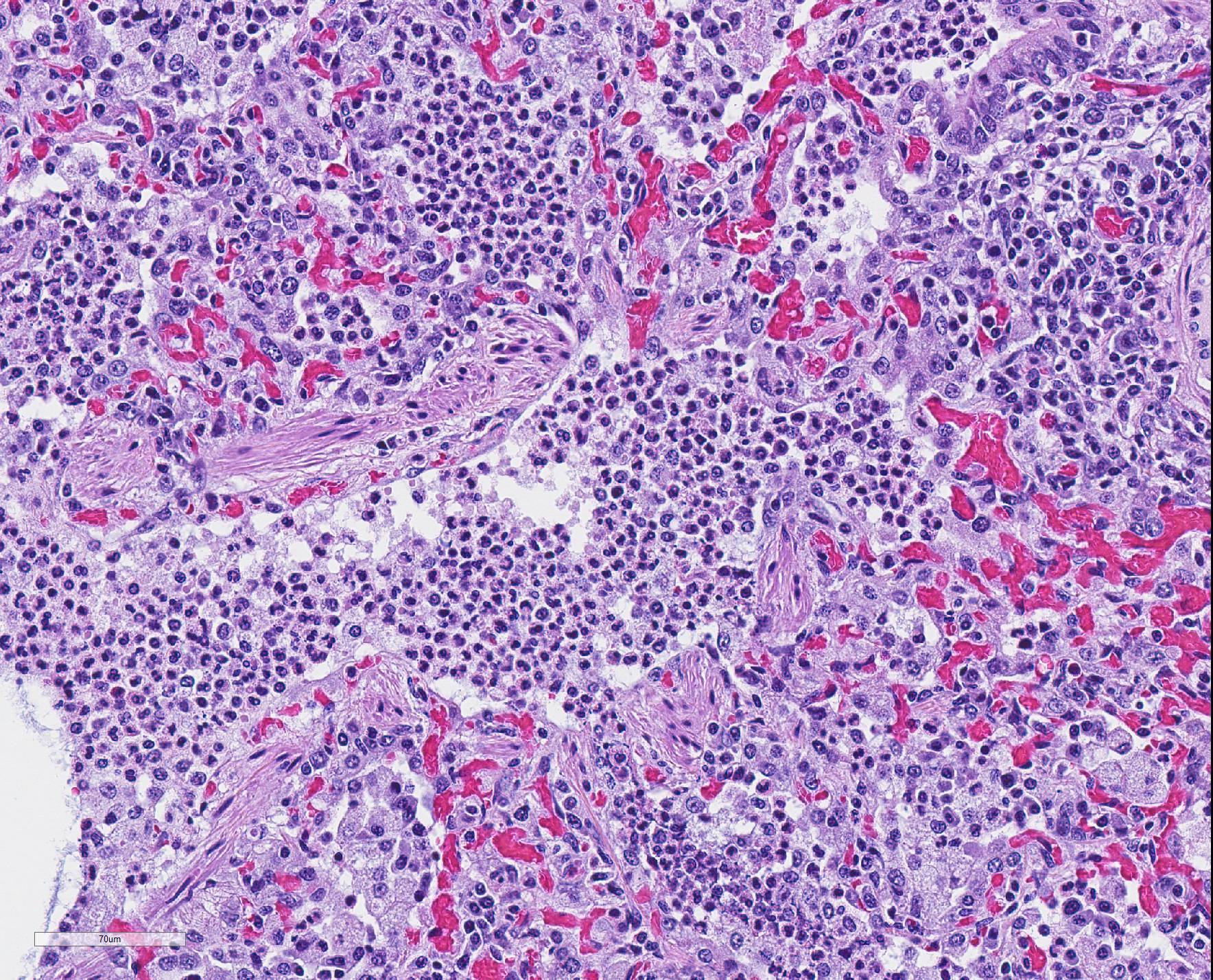

Microscopic Description: The interstitium within the section is diffusely infiltrated by moderate to large numbers of predominantly mononuclear cells along with edema. There is abundant type II pneumocyte hyperplasia lining alveolar septae and many of the alveolar spaces have central areas of necrotic macrophages admixed with other mononuclear cells and fewer neutrophils. Occasionally there is free nuclear basophilic debris in these alveolar spaces as well as proteinaceous fluid. Bronchioles are occasionally variably filled with neutrophils, and many regions of BALT are mildly hyperplastic.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Lung: severe, acute, regionally extensive to patchy, interstitial pneumonia with marked type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and intra-alveolar macrophage necrosis

2. Lung: mild, acute, multifocal, cranioventral bronchopneumonia with mild BALT hyperplasia

Contributor Comment: Gross and histologic lesions were consistent with a patchy, severe interstitial pneumonia in this case. The most predominant features of the pneumonia were abundant type II pneumocyte hyperplasia as well as the large number of necrotic macrophages admixed with basophilic nuclear debris within the alveolar spaces. These histologic features are highly suggestive of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus induced interstitial pneumonia; however these features are not always present depending on the chronicity of the pneumonia, among other variables.2 PRRS virus was detected in the affected lung with PCR and large numbers of macrophages had strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity with PRRS IHC.

PRRS is caused by PRRS virus, an arterivirus, and is characterized by two overlapping disease presentations, reproductive impairment or failure, and respiratory disease in pigs of any age.4 It causes estimated yearly economic losses of 660 million dollars in the USA and similar losses in most other countries.1 The respiratory syndrome is seen more often in young growing pigs but also occurs in naïve finishing pigs and breeding stock.4 In the respiratory syndrome, the virus is transmitted from an infected pig to the tonsil or upper respiratory system of another pig where primary replication occurs in lymphoid tissues.4 Viremia follows and may persist for several weeks.4 The virus infects and compromises the function of pulmonary alveolar and intravascular macrophages resulting in interstitial pneumonia and appears to increase susceptibility of the lungs to other pathogens.2 Secondary bronchopneumonia is common as was present in the current case.

Systemic infection commonly results in lymphocytic infiltrates in multiple organs, including lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis, myocarditis, endometritis and myometritis, and lymphohistiocytic meningoencephalitis and choroiditis, characterized by perivascular cuffs, vasculitis, gliosis and glial nodules.2 Vasculitis, fibrin thrombi and rarely fibrinoid necrosis may occur in any organ.2 A mild mononuclear vasculitis within the brain was also present in the current case, presumably due to PRRS.

Some pigs survive infection and become carriers, which is epidemiologically the most significant aspect of the infection. Commonly, once in a herd, this virus will persist indefinitely as the virus causes immune dysregulation during a critical time in immunological development, allowing the virus to persist.1 One recently proposed method for this persistence is altered thymocyte development due to the viral infection leading to ?holes? in the T cell repertoire resulting in poor recognition of PRRSV and other neonatal pathogens.1 Currently, there are no effective treatment protocols for acute PRRS infections, and vaccination has not been as efficacious as hoped.1 Prevention is the primary means of control.3

Contributing Institution:

California Animal Health & Food Safety Laboratory, San Bernardino Branch

https://cahfs.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/locations/san-bernardino-lab

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, lymphohistiocytic, diffuse, severe, with type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, intra-alveolar macrophage necrosis and marked peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphoid hyperplasia.

2. Lung: Bronchopneumonia, necrotizing and suppurative, diffuse, mild

JPC Comment: The contributor provided a concise but informative review of porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome.

This

particular virus is a global problem within the swine industry around the globe

and one of its most costly and continuing problem. Two genotypes exist, type 1

(Europe) and type 2 (North America). A number of difficulties are associated

with PRRS infection, including a high virus mutation rate which may result in

outbreaks in previously vaccinated herds, prolonged intection, and shedding via

a number of routes, to include ingestion, inhalation, venereal and transplacental

routes.3 Fortunately, the virus is relatively fragile in the

environment.

PRRS infection generally revolves around macrophage infection, initially in

tonsillar, nasal, or sites of pulmonary infection with infection of alveolar,

interstitial, and intravascular macrophages, bronchiolar epithelium, and

endothelium. Systemic viremia may occur in less than 12 hours with infection

of macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells in many tissues. Within the

lung, infection of macrophages results in markedly decreased macrophage

phagocytosis, oxidative burst and cytokine release, predisposing the lungs to

secondary bacterial infection. Additionally,

the virus induces the release of the immunsuppressive cytokine IL-10 from

infected macrophages, further diminishing both the innate and adaptive immune

response.3Apoptosis

of alveolar and intravascular macrophages are also common in infected animals

but may not represent a consequence of viral infection.2

A number of reproductive abnormalities are seen in infected herds. In naïve herds, upt to 50% of sows may abort and 10% may die. It is a recognized cause of SMEDI (stillbirth, mummification, embryonal death and infertility). Hemorrhage of the umbilical cord due to fibrinoid necrosis and suppurative inflammation of the umbilical artery has been considered to be a characteristic gross lesion.2 The persistence of one or more strains in endemic herds may result in continued losses from waves of abortions from successive generations of gilts.2

The presence of numerous necrotic macrophages and aggregates of bluish chromatin in the alveoli was considered diagnostic for PRRS by attendees. The moderator mentioned that while the presence of intra-alveolar necrotic macrophages are an excellent diagnostic feature for PRRS, they are not present in all cases. Some participants considered the presence of viable and degenerative neutrophils, especially within alveoli and smaller airways, evidence of a secondary bacterial infection further complicating the pneumonia in this pig. Attendees differed in their attribution of the BALT hyperplasia to either the interstitial pneumonia or a secondary bacterial infection.

While

discussing this case, the moderator walked the participants through a number of

differential diagnosis for lung diseases which should be tested for in cases

such of this. Epitheliotrophic viruses such as swine influenza and swine

coronavirus were discussed as potential viral agents, and bacteria such as Streptococcus

suis, Bordetella bronchiseptica, and Pasteurella multocida.

The moderator cautioned that some viruses, such as swine influenza, are present

for only a short time in the epithelium, and that immunohistochemistry for

viral antigen may be negative in more long-standing lesions.

The moderator also raised the possibility of this case being a case of ?proliferative and necrotizing pneumonia?, an acute disease of weaner and grower pigs, in which severe acute disease results in dyspnea. In this condition the entire lobe, or only cranial and middle lobes may be affected, and lymphadenopathy is a consistent feature. The etiology of this condition is yet unknpwn and may be the result of infection of certain strains of the PRRS virus, PCV-2, swine influenza, alone or in combination.2

References:

1. Butler JE, Sinkora M, Wang G, Stepanova K, Li Y, Cai X. Perturbation of thymocyte development underlies the PRRS pandemic: A testable hypothesis. Front Immunol. 2019; 10:1077.

2. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. The respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:523-526.

3. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of Microbial infection. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:214-215.

4. Zimmerman JJ, Benfield DA, Dee SA, Murtaugh MP, Stadejek T, Stevenson GW, Torremorrell M. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (porcine arterivirus). In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, eds. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2012: 52,461-480.