WSC 2022-2023

Conference 13

Case 2

Signalment:

20-month-old, female Droughtmaster, ox (Bos Taurus x indicus)

History:

Inappetence and weakness; pale mucous membranes; black, watery feces and reduced gut sounds.

Gross Pathology:

Jaundice. Subcutaneous and interstitial pulmonary oedema. Pale and yellow liver, marked distention of the gall bladder with mucoid bile.

Laboratory Results:

No findings reported.

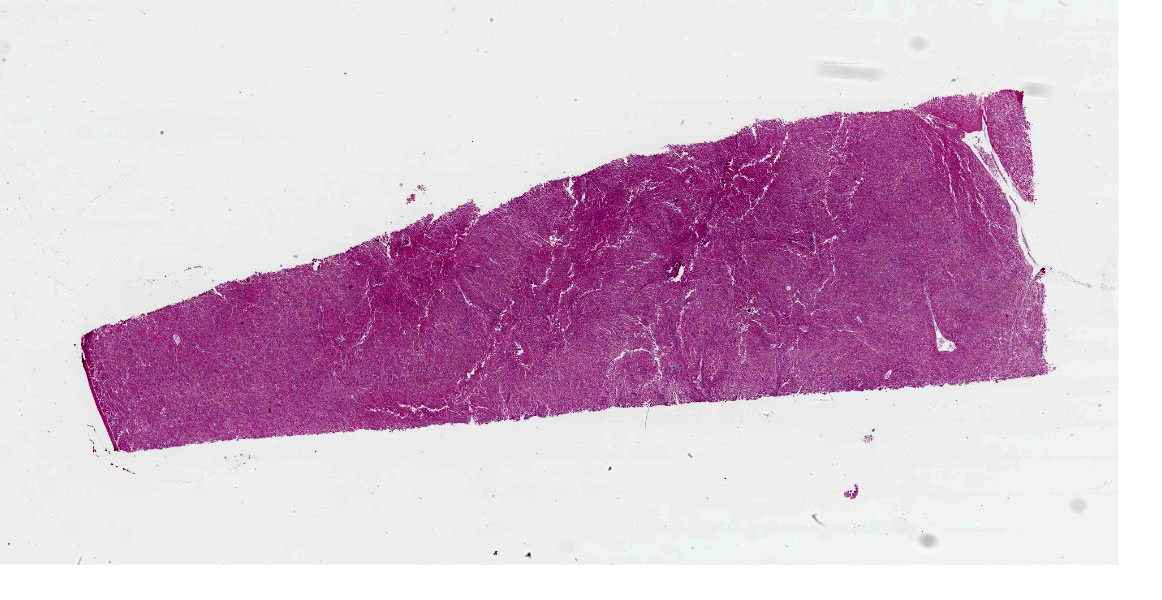

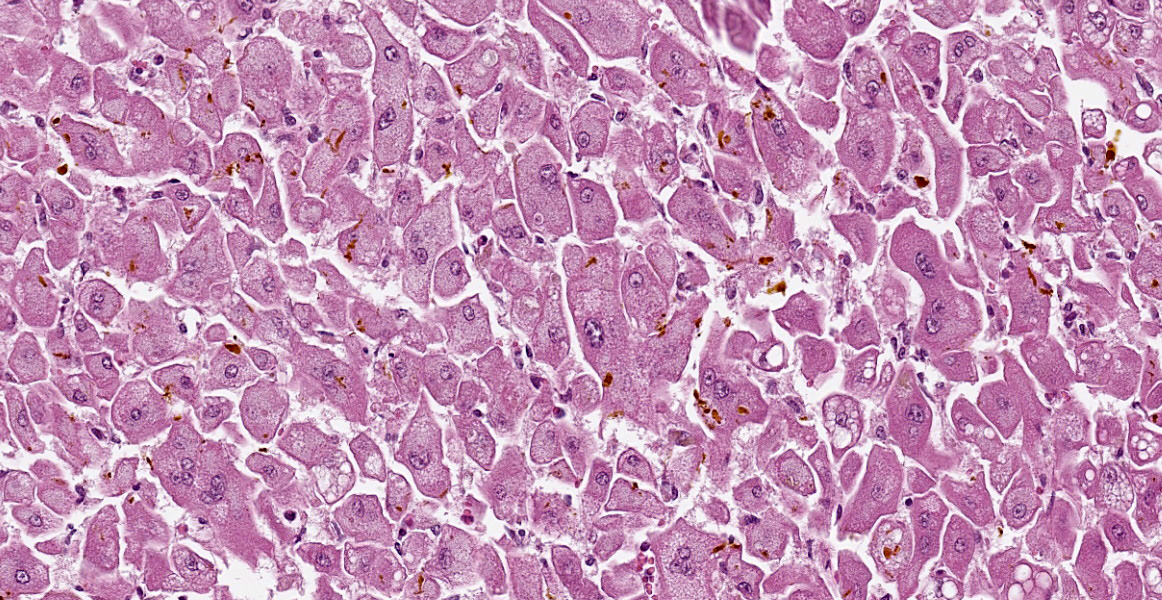

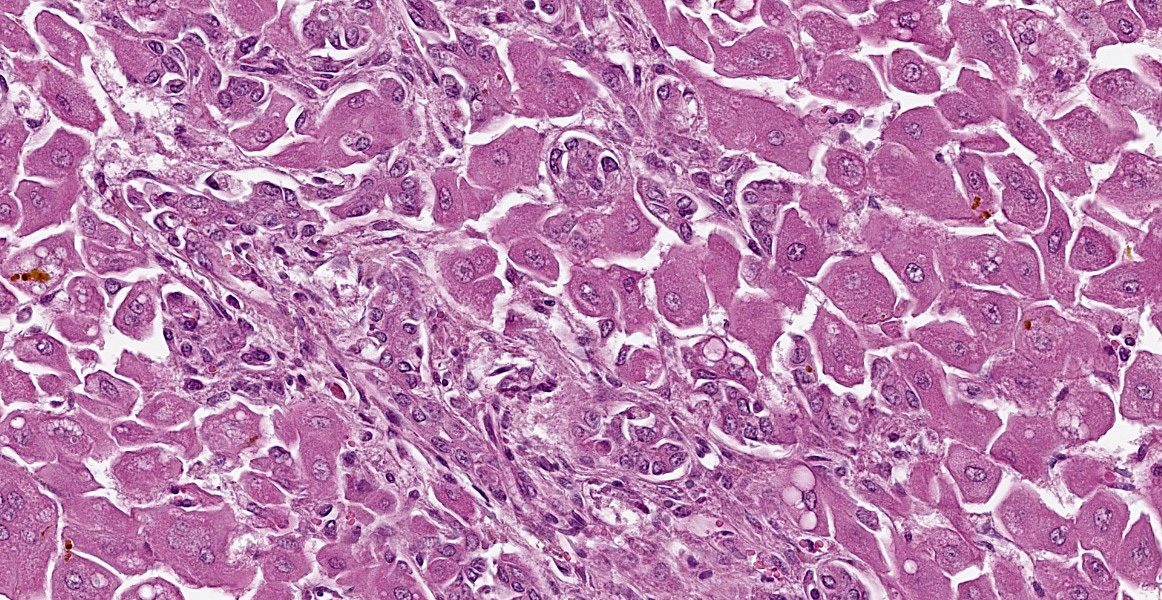

Microscopic Description:

There is diffuse hepatocellular disassociation. Hepatocytes are often enlarged and many are multinucleated, containing 2-4 nuclei. The cytoplasm of hepatocytes if often distended with fine vacuolation. Multifocally and often in centrilobular areas, there is mild to moderate distension of bile canaliculi with bile, this is also present within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. Multifocally, there is moderate biliary ductule hyperplasia. Multifocally, there is a mild, periportal population of lymphocytes and plasma cells with mild associated fibroplasia.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Liver: Hepatopathy with hepatocellular dissociation, cytoplasmic vacuolation and megalocyte formation; cholestasis and biliary hyperplasia.

Cholangiohepatitis, chronic, mild

Contributor’s Comment:

These findings are consistent with lantana toxicity. Lantana (family Verbenaceae) is an ornamental shrub that grows to a height of 2-3 meters and has red, pink or white flowers. It is native to the tropical and subtropical areas of Central and South America and is considered a pest in many parts of the world. The family contains species such as L. camara, L. indica, L. crenulata, L. trifolia, L. lilacina, L. involuerata and L. sellowiance however L. camara is the most widespread and of greatest toxicity to livestock.6 Its toxicity was first reported in Australia in 1910, this has subsequently been reported in many other countries. Livestock that are familiar with lantana rarely consume it voluntarily, toxicity mostly occurs in times of drought or when feed is otherwise scarce or in animals that have been brought in from lantana free areas.6 Cattle are most commonly affected; it is rarely noted in sheep and goats as they are less likely to eat the plant.7

The significant toxins in lantana are triterpene acids, lantadene A (rehannic acid), lantadene B and their reduced forms; lantadene A appears to be the most toxic of these. The toxic dose depends on the toxin content of the species of lantana.7 Clinical signs include jaundice, photosensitisation, inappetence and depression, ruminal stasis, constipation or diarrhoea with black, fluid faeces, dehydration and polyuria.1,6,7 Cattle ingesting a large dose of the toxin can die within 2 days however most cases are more chronic with clinical signs being evident for 2 weeks before death.7 The rumen can act as a toxin reservoir even after access to the lantana is prevented. Natural or experimental exposure to lantana results in increased bilirubin and globulins, there can be either a decrease or an increase in PCV. Decreased albumin and increased gamma glutamyl transpeptidase, sorbital dehydrogenase and arginase levels have been variably noted.1,6

Gross findings include jaundice; an enlarged, pale and yellow/orange or green-grey liver and a gall bladder that is distended, sometimes with mucoid bile; enlarged, mottled, wet kidneys and blood-stained fluid in the abomasum and small intestine.7 Histological findings include enlarged hepatocytes and fine hepatocellular cytoplasmic vacuolation which can be more evident in periportal areas and bile accumulation which is often more pronounced in periacinar zones. There is also often bile duct proliferation and, in some cases, periportal apoptosis or necrosis of hepatocytes.7 The gall bladder can demonstrate mucoid metaplasia of the epithelium with haemorrhage, ulceration, inflammation and necrosis.1 The kidneys often demonstrate mild to severe vacuolar change or necrosis of the tubular epithelium with extensive tubular cast formation.1,7 There can also be ulceration of the abomasal mucosa.1

The toxin is thought to cause collapse, distension or microvilli damage in bile canaliculi. The mechanism of cholestasis is still unknown however damage to the contractile pericanalicular cytoskeleton or the cell adhesion molecules is possible.7 The role of hyperbilirubinaemia in the nephropathy is unknown. Myocardial necrosis has been noted in sheep and may be responsible for death in animals that die early in the course of the disease.7

Contributing Institution:

Dr Mirrim Kelly-Bosma, School of Veterinary Science, University of Queensland, Gatton campus, Gatton, Queensland, Australia, 4343. (https://veterinary-science.uq.edu.au/)

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatocellular dissociation, megalocytosis, multinucleation, rarefaction, lipidosis, diffuse, severe, with ductular reaction, and canalicular cholestasis.

JPC Comment:

This case illustrates a different pattern of hepatotoxicity compared to the centrilobular necrosis in Case 1 of this conference. In addition to the mechanisms of toxicity mentioned by the contributor, studies in rats have suggested that metabolites inhibit mitochondrial respiration and that reduced lantadene A may be more toxic than lantadene A.4 The toxin targets the bile canalicular plasma membrane, causing impaired hepatobiliary excretion and intrahepatic cholestasis. The toxins inhibit neural impulses and ruminal stasis.3,4 Hepatocellular megalocytosis is speculated to be due to enlargement of the rough endoplasmic reticulum.

Key histologic findings, as covered by the contributor, include hepatocellular megalocytosis with cytoplasmic vacuolization and canalicular cholestasis. Dr. Cullen also remarked on the pronounced individualization of hepatocytes, a phenomenon which is also seen in leptospiral infections.

Other hepatotoxins which cause megalocytosis are pyrrolizidine alkaloids and aflatoxin.2 Repeated exposure to pyrrolizidine alkaloids causes megalocytosis with hepatic atrophy, while ingestion of large quantities causes acute centrilobular necrosis.2 Similarly, prolonged exposure to low levels of aflatoxin can cause megalocytosis during with scattered necrosis.2 Acute aflatoxin toxicosis in large animals has only been documented in experimental settings because there are insufficient quantities in moldy feed to induce acute injury.

Another key clinical and histologic feature for lantana toxicosis is cholestasis, and in herbivores, cholestasis can quickly lead to type III (hepatogenous) photosensitization due to the lack of biliary excretion of chlorophyll breakdown products (phylloerythrins) in the blood.2 When deposited in the skin and exposed to UV light these pigments cause reactive oxygen species formation and tissue damage.5 Hepatogenous photosensitization is usually caused by mycotoxins and hepatotoxic plants, including sporidesmin and lantana, although it has been associated with a wide range of plants, including normal forage crops like Bermuda grass.5 Grossly, photosensitization manifests as erythema, edema, and necrosis in sparsely haired or unpigmented skin, and affected animals are pruritic. Histologically, there is edema of the dermis and coagulative necrosis and vesicles in the epidermis.5

References:

- Black H and Carter RG. Lantana poisoning of cattle and sheep in New Zealand. N Z Vet J. 1985; 33: 136-137.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and Biliary System. In: Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. Elsevier: 2016; 329-339.

- Kumar R, Sharma R, Patil RD, et a. Sub-chronic toxicopathological study of lantadenes of Lantana camara weed in guinea pigs. BMC Veterinary Research. 2018; 14(129):1-13.

- Manthorpe EM, Jerret IV, Rawlin GT, Woolford L. Plant and Fungal Hepatotoxicities of Cattle in Australia, with a Focus on Minimally Understood Toxins. Toxins. 2020; 12(707):1-25.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary System. In: Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Elsevier: 2016; 577-580.

- Sharma OP, Makkar HPS, Dawra RK, et al. A review of the toxicity of Lantana camara (Linn) in animals. Clin Toxicol. 1981; 18; 1077-1094.

- Stalker MJ and Hayes MA. Liver and biliary system In: Maxie MG ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. Fifth ed. Elsevier, 2007: 297-388.